Covering all issues

involved with the break-up of Yugoslavia is not an easy task as it has to take in

account the differing sides and ethnic communities of six republics involved in

Yugoslavia. It furthermore should clarify previously neglected details like for

example why among others, the World War II concentration camp Jasenovac in the

Independent State of Croatia (NDM, became a contested site for competing

memories between Serbs and Croats in Yugoslavia. At Jasenovac, the most

infamous camp in the NDH, Croatian Ustaga killed

thousands of Serbs. After the war the new communist leader, Josip Broz Tito,

decided to mask the ethnic dimensions of this tragedy. In the official

narrative of Jasenovac there was no mention of the targeted victims (Serbs,

Jews, and Gypsies). While the way to achieve justice and heal the wounds of

those injured would have been to memorialize the atrocities truthfully, Tito's

official narrative of World War II impeded reconciliation and healing. Tito's

decision to cover up WWII ethnic conflict had several consequences. Without

justice there is no healing and without healing it is more likely the violence

would eventually re-erupt, in a cycle of revenge. And while the underlying

economic and political conflicts that precipitated the violence remained

unresolved; with no commitment to discovering the truth about Jasenovac and

other mass atrocities during WWII, later national narratives appeared without

constraint, which only further inflamed the hatred between in this particular

example, the Serbs and Croats (Croatia started EU membership talks along with

Turkey in 2005 and may join the EU by the end of the decade). We

will in fact cover Jasenovac related issues in Belgium to

Kosovo P.4. But the

importance of studying the phenomenon of nationalism furthermore is to

understand its challenge to international peace, stability, and relations in

the growing number of violent conflicts described and justified in terms of

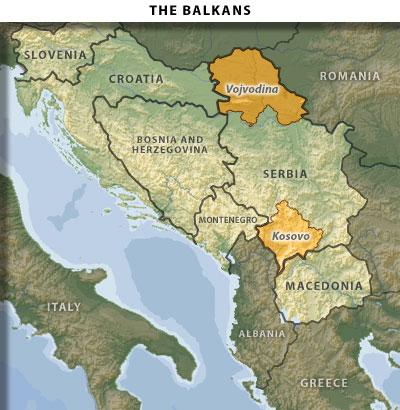

ethnicity, culture and religion. As the experience with Yugoslavia‘s six

republics, and the Balkans as a whole once more illustrates, nationalism can be

a potent divider of ethnic groups and a dangerous, even deadly tool driving

people into a civil war. Hence, it should not surprise that Nationalism is

often used as a scapegoat and a mask for real intentions or reasons behind a

conflict. It is oftentimes a tool for reaching political aims. This was for

example evident in Bosnia and Herzegovina in which after recognition Bosnian

Serbs pledged their allegiance to Republika Srpska

and Belgrade while Bosnian Croats did the same to Herzeg-Bosna and to Zagreb.

What we thus set out to examine with „From Belgium to Kosovo” is also,

the extent to which historical claims to statehood and/or memories of statehood

play a role in decision-making regarding whether an entity becomes a state and

whether it is recognized as such by the international community. Whether

historical memories and statehood have an impact on entities' drives and desires

to achieve statehood; whether historical memories or drive towards independence

play a role in the decision to grant recognition to an aspiring entity; the

role of nationalism and the extent to which it can be on the one hand a potent

force that unites ethnic groups and on the other a deadly, destructive

mechanism that can be manipulated to accentuate differences, promote hatred and

deepen a divide between ethnic groups. The working definition of a state for

the purposes of analyzing the upcoming three cases of Slovenia, Croatia and

Bosnia; is that it is the authoritative and legitimate political institution

that is sovereign over a recognized territory.1 Additional criteria that will

be considered are the general criteria outlined in the Montevideo Convention requiring each state to have a permanent population,

defined territory, government and ability of that government to enter into

relations with other states.

Slovenia

The Slovenes were

converted to Catholicism in the 10th century and fell under the dominion of the

Habsburg Empire in the 13th century. They remained a part of that empire until

the 20th century and as such their primary "other" for much of their

history was the Catholic Austrian and Hungarian Empires. As such, there was a

time wherein the Slovenes were somewhat separated from their heritage - as in

the Czech case. The reformation had some impact in Slovenia, but was quickly

quelled by the counterreformation. In addition, during the 19th century, as

Slovene identity began to strengthened, it did so in response to Hungarian and

Austrian identity. The presence of the Ottoman Turks was, however, always

apparent, and often disrupted Slovenian life. As a result, the religious

dimension never fully subsided. Once Slovenia was integrated into the Yugoslav

state, the Serbian efforts at dominance created tension within the Slovenian

community as it did in the Croat community. Ultimately this tension proved less

severe than the Serb-Croat tension. As a result, although there is no current

religious frontier for Slovenia, the frontier created by a Serb-dominated

Yugoslavia in the latter part of the 20th century did lead to Catholic ties to

Slovenian Nationalism. The main threat to Slovenian identity over the years has

come from Austrian and Hungarian dominance. This fact changed, however, in the

20th century with the creation of Yugoslavia. As a result of the multiple

religions within the Yugoslav state, a new emphasis was placed on Catholicism

in Slovenia. When Yugoslavia crumbled in the 1990s, Slovenia was the first to

move for independence - an act that led to a brief war between Slovenia and

Yugoslavia. The Slovenian victory allowed for a swifter transfer to independence

than was possible in Croatia or Bosnia. As a result, there was a clear threat

involved (a 10 day war was fought); however, the threat was less than in other

former Yugoslav states. The impact is clear. One could argue that the public

presence of the Catholic Church in Bosnia and Croatia, manifested in the

affirmation of the collective-national as a dominant social value, and the

failure of the Slovenian Catholic Church to have the same role and influence,

was shaped by the conditions of the wars in Bosnia and Croatia and the mainly

peaceful transition from communism to democracy in Slovenia. Therefore, the

religious frontier in Slovenia was less significant than in many of its

neighbor states, and when it was significant, the threat was relatively minimal.

Nationalism in Slovenia is, as a result of the mixed circumstances listed

above, partially linked to religion and partially secularized. In terms of

demographics, the Slovenian people are largely Catholic - over 71 % in the 1990

census. Interestingly enough, in the ten years to follow, the rate of self identification dropped rather drastically to slightly

over 57%. It is no coincidence that the significantly higher figure occurred

during a time of national struggle for independence from a religiously differentiated

group - the Orthodox Serbs. This shift to secularism has continued, but it has

been accompanied by a continued emphasis on religious identity in society. For

instance, "In the period from September 2001 to February 2002, mass media

have participated in the perpetuation of the dominant perception of the Muslim

community and Islam as inherently alien to Slovenia. In addition, there is a

formal separation of religion and state, and this is reflected in policies such

as abortion (Slovenia allows abortion in most cases). Religion played an

important part in Slovenian nationalism for a relatively brief period of time.

The modem concepts of

nationalism did not develop among Slovenes until the eighteenth century largely

due to the fact that for many centuries they lived as part of a medieval

Europe. This is mainly because the Slovenes enjoyed the same rights as other ethnic

groups and felt no need to express their 'separateness'. In the thirteenth and

fourteenth centuries most Slovene lands became a part of the Habsburg feudal

domain. Until 1918, the majority of Slovenes lived in the Austrian half of

Austria-Hungary.2This fact is essential in understanding many differences

between the Slovenes and the Serbs.3 The very first Slovene national program

was formulated in 1848 with a goal of unifying their administratively split

ethnic territory into one. Since the Slovenes did not have a medieval tradition

of statehood, their demands were based on the principle of natural law.4

Until the fall ofthe Dual monarchy, the demand for a unified Slovenia

remained the main goal of the Slovene national movement, which took on a mass

character in the second half of the nineteenth century.5 The period ftom the French Revolution to the Congress of Vienna, 1789

to 1815, drastically changed the lives of all Europeans, including the

Slovenes. For the intellectuals, French political thought combined concepts of

nationhood and homeland that will become a political entity at some point in

the future.5 Slovenes were significantly affected by two decades of war and

between 1809 and 1813 found themselves under French Imperial rule. During the

four-year lifespan of France's Illyrian provinces, its population was exposed

to an enlightened French administration. The French encouraged the use of the

local language, which they preferred to the use of German, the language of the

defeated Austria. Slovenes used the vernacular in schools, courts, newspapers

and text books. Some Slovenes even enjoyed the privilege of being part of the

French administration, which had its seat in its current capital, Ljubljana.

The liberties Slovenes enjoyed during this period in time had a significant

role in the development of a sense of unity and nationhood.

It thus was after

1815 the Slovenes embarked on the nationalistic road, passing the point of no

return.6 Slovenian nationalism did not have a proper opportunity to flourish

until the Habsburg rule which was validated by the Treaty of Vienna in 1815. As

in most historic cases of nationalism, it was the intellectuals and clergy that

shaped Slovene identity. The first political agenda for "United

Slovenia" was formulated in 1848 by a group of intellectuals who promoted

the joining of all Slovene inhabited lands within the Habsburg Empire and the

right of public use of Slovenian language in schools and administration.7 The

Slovenes who were for the most part satisfied with their rights and freedoms

within Austria, were not separatists, and practiced non-secessionist

"quiet nationalism.“8 This urge for the unification can only be

interpreted as a desire to preserve and further develop their culture and

preserve Slovene tradition. Slovene aspirations for statehood became pronounced

in the final stages of the Habsburg Empire in the 19th century as the Slovenes

for the first time began to think of themselves as being a nation. This drive

developed simultaneously with Slovenes becoming more aware of their uniqueness

and separateness from other peoples in Europe. This delay in expressing a

desire for a separate state was largely due to realpolitik thinking of the

pre-1914 era that favored the powerful nations like France and Germany, that

possessed large militaries and sound economies. The thinking of the time made it

clear that the small nations of central Europe were better served operating

under the umbrella of the Habsburg Empire. Its proclaimed raison d'etat was

protecting small national communities such as that of Slovenia of only one

million.9

It was evident that

the political climate at the time did not favor formation of small states which

likely played a role in the lack of aspirations for independence of small

entities. Hence, even if there was a secret desire among the Slovenes to form

their own entity, the idea would not have been supported by powerful Empires

and states which controlled the international arena. In their eyes, smaller

states were unable to defend themselves and would have only weakened the

stability in Europe. The first time Slovene socialists' made a

contribution to the idea of Yugoslav ism, was in the Tivoli Resolution of 1909.

Along with political demands, the Tivoli document contained a comprehensive

cultural program, advocating cultural amalgamation. It called for the national

unification of all Southern Slavs, irrespective of name, religion, alphabet and

dialect or language.In the years before the First

World War, all three Slovene parties, the Catholic, Liberal, and Social

Democrat party together and introduced the Yugoslav idea. The dissolution of

Austria-Hungary which came with the end of the First World War in 19 presented

an opportune moment for the realization of unification goal which was achieved

on December 1, 1918 between the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (SCS)10 and

the Kingdom of Serbia.11

The period between

the unification and the adoption of the constitution on June 1921 represented a

period during which provisional authorities were to accomplish the transitional

tasks of getting the state's boundaries recognized and signing the peace treaty.12

The borders of the Kingdom were established at the Versailles Peace Conference

which commenced on January 18, 1919.13 In order to ensure its political status,

peace, stability and borders SCS signed several international agreements.14 The

creation of SCS did not mean however that the South Slavs would befree of

foreign intrigues and hostilities. The defeated powers in World War I, as well

as Italy, made no secret of their hostility towards the new state, a hatred

that was to continue for the two decades of the First Yugoslavia's existence.

Italy, which was present at Versailles, strongly resisted the creation of SCS.

This was largely due to its interest in acquiring some of the SCS territories.

On September 12, 1919 Italy occupied the city of Rijeka. Pressured by the

Entente powers to sign the peace agreement with SCS, Italy returned Rijeka in

exchange for islands of Cres, Losinj, Lastovo and Paiagruza.15 The first Great Power to recognize

the new state was the United States in February 1919.16

The history of the

first Yugoslavia ended in collapse as Germany and Italy invaded a weak and

divided country on 6 April 1941. The Nazis were able to break the country up,

making Serbia a German Protectorate, annexing parts of Slovenia and Istria to

Italy, and creating a so-called Independent State of Croatia on the territory

of Croatia and Bosnia. After the Second World War on November 22, 1945,

Yugoslavia was united as a Socialist Federal Republic (SFRJ) by the Partisans

and it consisted of six republics and two autonomous provinces. The old

Yugoslavia was recreated as a federation in which each of the South Slav

peoples would have a framework for self-determination and a stake in the new

state. Slovenia was one of the six republics which in the SFRJ enjoyed great

economic prosperity and was allowed to develop politically while having equal

rights as the other republics. The root of Slovene nationalism was based on the

belief in the linguistic and cultural distinctness of the Slovene people. Since

the 19th century, Slovene intellectuals had standardized the language and used

it to create sophisticated literary writings. Intellectuals promoted belief

that the federal republic of Slovenia and its legislative and political

authority was the chief political instrument in the task of guarding its

cultural distinctness.17 This belief will remain a central argument for

Slovenian nationalism and quest for independence. Today's Slovene intellectuals

often consider themselves as successors to the creators of Slovene nationhood,

with a task of guarding its cultural and linguistic distinctness. From their

point of view the federal republic of Slovenia, and its legislative, economic

18 and political autonomy was the chief political instrument in this task.

The most real and

tangible threat to Slovenenian uniqueness and

distinctness, as well as autonomy, was expressed in a Memorandum 19 of the

Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1986. This document, though never

officially published, was widely circulated. What caused the uproar was the

rather strong tone of certain chapters, which proclaimed that the entire

Serbian race was threatened by an anti-Serb conspiracy. It stated: "The

physical, political, legal and cultural genocide of the Serbian population in Kosovo

and Metohija is the worst defeat in its battle for liberation that the Serbs

have waged from 1804 until the revolution in 1941.“20 The Memorandum further

faulted Slovenia and Croatia for their economic development which far exceeded

that of Serbia and poorer republics mainly Kosovo and Metohija. It cites that

this economic superiority was achieved through political influence and

manipulation.21 The document also points out that the integrity of the republic

had been destroyed and that the "Serbian people cannot peacefully wait in

such a situation“22. This sentence left the Slovenes wondering as to what

action the Serbs might take to remedy it. Without a doubt the Memorandum was

written as a reaction to the realization on the part of Serbian elite that

their political and economic development was lagging behind that of Slovenia

and Croatia. Often unfounded accusations directed towards Slovenia were made

out of fear that Slovenia has reached the highest level of independence and

development and that it would soon result in their request for independence

from Yugoslavia. Slovenia defended the Albanians in Kosovo in part as it felt

threatened.23 However, it soon realized that their focus should be on guarding

their own sovereignty, which resulted in their abandonment of Kosovo. The

Memorandum was the key political tool which Slobodan Milosevic abused in order

to portray Serbs as victims and climb to power in 1987. He promised to make

Serbia 'whole' again by repairing the damage done by the 1974 Constitution and

ending autonomy for the provinces. Milosevic's campaign against the Albanians

in Kosovo and for the restoration of the province to the republic, using

'street democracy', frightened other Yugoslavs.

Partially in response

to the draft, in 1987 the editors of the Ljubljana based journal Nova Revija requested from a diverse group of Slovene

intellectuals their views on the Slovene national programme.

Several authors pointed to the absence of Slovenian armed forces and argued for

the need to assert Slovenia's sovereignty and the formation of its own military

force.24 The main concern for all the authors was finding the right road for

Slovenian independence in the future. In the early 1980s the first political

dissident groups emerged in Slovenia. Two prominent examples included the

Alternative movement comprised of Slovene youth (Mladina).25

Their true ambition was disassociation from the Balkan Southerners, mainly

Serbs, who according to this group lacked European culture.26 Milan Kucan, who

became a prominent politician and president of Slovenia, voiced his opposition

by saying: "Slovenes cannot regard as their own any state that does not

secure the use of their mother tongue and its equality and in which the

freedom, sovereignty and equality of the Slovene people is not guaranteed.“27

The first alternative political party, the Slovene Democratic Alliance was

formed and Nova Revija, became its platform for the

free expression of nationalistic sentiment. Founder of the new party, Dimitrij

Rupel was one of the contributors to the 1987 Nova Revija

issue arguing for Slovenia's political as well as cultural independence. Joze Pucnik, who was also a contributor for Nova Revija, formed the Slovene Democratic Alliance, committed

to the drafting of a new Slovenian constitution and institutionalizing the

republic's sovereignty.28

This encouraged the

establishment of more parties such as the Slovene Christian Democratic Party,

the Green Alliance and the Slovene Craftsmen's party, the Slovene Farmers'

Alliance, all of which having already worked together in the Committee for the

Defense of Human Rights, formed the opposition coalition bloc in January 1990

famously known by its Slovene acronym DEMOS. In September 1989, Milan Kucan

asserted Slovenia's right to secede from the Yugoslav federation.29 A series of

constitutional amendments was passed by the Assembly of the Republic of

Slovenia enabling the republic's organs to proclaim a state of emergency in the

republic and codifying the Slovenian state organs' duty to defend and protect

the republic against any federal organs.30 This represented the first in the

series of legislative moves asserting full Slovenian sovereignty over its

affairs. Another important development was the transformation of the Communist

party of Slovenia into a Slovene National Party. A member of the Committee memorably

claimed that in the process the Communist party 'highjacked' the national cause

from the Committee for the Defense of Human Rights for its own purposes. 31 The

Slovene Communist Party delegation walked out of the Fourteenth Extraordinary

Congress of the Communist party of Yugoslavia in January 1990, refusing to be

outvoted on its proposal to confederalize the

Yugoslav Communist party. It soon took drastic measures by abandoning Marxism,

changing its name, programme, flag and image and

adopting a new slogan 'Europe now', while presenting itself as a national party

of the Slovenes fighting for a sovereign state within a new confederal

Yugoslavia.32 While the opposition DEMOS parties differed greatly among

themselves in their ideological programmes, they were

united in their rejection of Yugoslavia as an 'exhausted concept'. In the

elections for the lower chamber of the Slovenian assembly in April 1990 the

communist Party of Democratic Renewal got 55 per cent of the vote; the

coalition formed the first post communist government

in Yugoslavia with the prime minister Lojze Peterle. In the second round of

voting, Milan Kucan won the presidential election. Even though they held

different political views, former dissidents were in the Government, united by

a common goal of Slovenia's independence and secession from Yugoslavia. The new

Slovene government accelerated preparations for Slovenia's independence, by now

supported by an overwhelming majority of Slovenes. At a referendum held in

December 1990,88.2 per cent voted for independence.33

The Struggle

Serbia and its

satellites within the Collective Presidency of the SFRY decided to block the

automatic rotation to the office of President of the Presidency that is,

nominal head of the SFRY, to the Croatian representative, Stipe Mesic. The

Serbian bloc did so to create conditions for a 'state of emergency' in which

the army would declare martial law. Although Serbian representative to the

Collective Presidency Borisav Jovic had discussed this possibility with army

chief General Veljko Kadijevic, it did not emerge as Kadijevic opted to act cautiously and, in his own

terms-constitutionally. 34 From this point the SFRY, already crippled by the

inter-republican quarrels, ceased de facto to function. Mesic argued that the

purpose of this was to end Yugoslavia.35 The leaders of the national parties

anticipating that the Jugoslav National Army (JNA) would provide resistance to

their quest for independence started forming their own armed forces. While

Slovenes were opening champagne bottles and celebrating on the streets of

Ljubljana, the new government was preparing for a military confrontation.26

Slovenia utilized its intelligence network in the Yugoslav army's headquarters,

and discovered the army's plans to counter the Slovenian take-over of Yugoslav

federal institutions in Slovenia.27

The Yugoslav army

high command viewed Slovenia's planned secession as part of a foreign,

primarily German, plot to partition federal Yugoslavia and thus to weaken its

armed forces. The JNA saw it as their constitutional duty to preserve and

protect the territorial integrity of the country and prevent any partition. By

seeking to instigate military confrontation, the Slovene government hoped to

achieve not only unity in Slovenia but European intervention and an

international recognition of its independence. The major obstacle to their

independence was the refusal of the US and the EC to recognize any unilateral

secession of Yugoslav republics.28 However, Slovenia made one of its wisest

diplomatic decisions by establishing contacts in Austria, Germany and other

European countries and making the argument for European security. The Slovenes

claimed that the conflict would not only be a threat to Slovenian security but

also a threat to Europe as a whole. Placed in the context of European security,

the conflict in Yugoslavia attained a new dimension.29

One of the main

tactics of the Slovene defense ministry was its clandestinely imported weaponry

to be used for a show of force that hardly anyone in Belgrade anticipated. On

25 June 1991, the day of the proclamation of independence, the initial Slovene

operations moved forward by taking over the international border crossings in

Slovenia and erecting a border crossing with the federal republic of Croatia.

By using the intelligence from the Yugoslav federal army's headquarters, the

Slovenian forces were initially able to stop almost all of the Yugoslav army's

armed units as they moved out of their barracks in Slovenia to regain control

over borders crossings.30 The Slovenian resistance took many by surprise. Many

believed that the JNA miscalculated in Slovenia. On 27 June 1991 the JNA

assumed that the Slovenia's Territorial Defense Force (TO Slovenska

Teritorialna Obramba) would

give up its efforts based on a mere show of force by the JNA. The JNA also

presumed that its efforts would be supported by the international community,

which at this point stood on the sidelines watching the events unfold.31 The

short 'Ten Day War' ended rather swiftly with Slovenian victory. The main

purpose of the war was to demonstrate to the Slovene population the alleged

hostility of the Yugoslav federal government and remove any remaining

allegiance to the Yugoslav state.32 The process was portrayed as national

liberation, which in many ways strengthened Slovenian patriotic feelings and

reinforced citizens' allegiance to Slovenia. Additional reason for its

perception as a success was a minimal number of casualties. Only 8 Slovene and

39 JNA soldiers died and 111 Slovene and 163 JNA troops were wounded, while

more than 2,500 JNA conscripts were taken prisoner.33

The Slovenian

government, immediately upon the outbreak of the conflict, asked the EC and the

Council for Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) to intervene.34 In May

1991 the EC troika35 consisting of the foreign affairs ministers of the

Netherlands, Luxembourg and Italy, diplomatically intervened into the Slovenian

war, while contributing to war's end.36 Both organizations promptly obliged

within two days of the outbreak of the conflict. The EC sent its troika to

negotiate in Belgrade and the CSCE entrusted the EC with its peacekeeping

mission in Slovenia. The first cease-fire negotiation by the troika broke down

almost immediately and the troika returned to the island of Brioni on July 8,

1991 to negotiate a peace agreement, which defacto

recognized Slovenia's independence. The Brioni Declaration endorsed by all six

republics and the federal presidency required the Yugoslav army and federal

government to hand over the international border crossings. The Slovenian

government was to lift the blockade of the army's units, deactivate its defense

forces and, together with the Croatian government, proclaim a three-month

moratorium on its declaration of independence. The EC, acting on behalf of the

CSCE, also sent an observer mission of unarmed officials, which was to monitor

the cease-fire and the compliance with the military aspects of the agreement.

37

Many Slovenes were

dissatisfied with this outcome. For them the moratorium and the renewed

negotiations among the six republics meant that Slovenia was being forced, by

the EC, to remain within Yugoslavia against its will. While refraining from

granting Slovenia independence, in agreeing to the Brioni Declaration, the

Yugoslav federal government in effect gave up its jurisdiction in the

republic.38 This decision was followed by the action of the Yugoslav state

presidency, under the chairmanship of the Croat representative, which decided

on 18 July, to withdraw unilaterally all army units from the republic. Serbia

accepted the Brioni Declaration because Slovenia's secession was unavoidable.

The idea of federal Yugoslavia was already been dead. This reality left very

little leverage to Milosevic and his government in Belgrade. In the following

five months Slovenia prepared for independence, it solidified its own

government in Ljubljana which by now operated independently trom

Belgrade. Slovenia officially requested recognition from the European Community

on December 19, 1991.

Thus this case study

so far has slown, that Slovenia does not have a clear

historic record of independent statehood. In the period prior to World War I,

Slovenia was part of the, Habsburg Empire under which it enjoyed certain

privileges and had the opportunity to develop its own culture and identity.

Under Yugoslavia, Slovenia continued to develop its own language, culture and

distinct mentality different from that of other Yugoslav republics. It

developed solid political and economic ties with its Western neighbors such as

Germany, Austria and Italy. Even though there is no record of a strategy on the

part of Slovenes to secede from Yugoslavia, the steps that were taken prior to

1989 made the process of independence much easier to obtain. The Slovenian republic

was to a large extent mono-ethnic, it had a potential to become economically

independent; it had its own culture and identity, its own education system and

a language distinct from that of other republics. Economically Slovenes were

much more developed than the rest of Yugoslavia. This fact was always a source

of grievance for the Slovenes. This "separateness" evident in their

language and economy helped mobilize Slovenes in their quest for independence.

The Slovenian case

indicates that the prior existence or a historical record of statehood is not a

requirement in order for an entity to develop an aspiration towards statehood

or to be recognized by the international community. Slovenia used a clever strategy

and developed strong ties to Austria, Germany and Switzerland and lobbied for

their support in recognizing its independence. The deciding factors had to do

with the circumstances, its geographic location, and its distinctness as well

as willingness of the government in Belgrade to allow Slovenia to leave the

Federation. In the long run Slovenian secession and early promises of

recognition had a domino effect. It started an irreversible spiral. At the

time, Croatian President Franjo Tudjman stated that if Slovenia declared

independence, Croatia will immediately follow with the same course of action.

Slobodan Milosevic decided to "let Slovenia go" because there were

hardly any Serbs living on its territory which meant Serbia couldn't make any

claims for its territory. But his focus was on Croatia and Bosnia, Macedonia

and creating greater Serbia. The fact that Slovenia gained independence did not

disrupt his plans.

Slovenia satisfied

the general criteria for statehood. It had a defined territory as it had clear

and undisputed borders; it had a permanent population consisting mostly of

Slovenes; it had a government in Ljubljana which had full capacity to conduct

international relations and had already developed sound relations with other

countries especially Austria, Germany and Italy. In addition to the basic,

general criteria, Slovenia had legitimate government that exercised full

control over its population, it had enacted laws and its constitution which

guaranteed protection of minorities, it developed its own army and by the time

of independence, Slovenia was by far the most advanced economically of all the

other republics. The case of Croatia however was a lot more complicated as its

independence and recognition involved many unresolved and disputed issues.

1 Adeed

Dawisha and I. William Zartman, Beyond Coercion, pp.

6-7.

2 The census of 1910

indicated that the 1,253,148 Slovenes represented 4.48 per cent of the citizens

of this western half of the monarchy. See Fran Zwitter,

Nacionalni Problemi v Habsburski Monarhiji, p. 224 392

Due to their close relationship with Austria, the Slovenes over the years

always claimed that they were part of the West and tried to disassociate

themselves from the 'Balkans' and the Serbs. In addition, their relationship

with the West also explains the difference in mentalities as well as a deep gap

in economic conditions and development.

3 The term natural

law refers to a type of moral theory, as well as to a type of legal theory,

despite the fact that the core claims of the two kinds of theory are logically

independent. According to natural law in ethical theory, the moral standards

that govern human behavior are objective, derived from the nature of human

beings. According to natural law in legal theory, the authority of at least

some legal standards necessarily derives from considerations having to do with

the moral merit of those standards. There are a number of different kinds of

natural law theories of law, differing from each other with respect to the role

that morality plays in determining the authority of legal norms.

4 Jill Benderly and Even Kraft, Independent Slovenia p. 27

5 Fran Zwitter, "Narodnost in

Politika pri Siovencih

(Nationality and Politics Among the Slovenes) Zgodoviski Casopis

I, in Jill Benderaly and Evan Kraft, Independent

Slovenia; Origins. Movements, Prospects 1944 pp. 6-7.

6 Carole Roogel, The Slovenes and Yugoslavism,

/890-/9/4 New York: East European Monographs in Jill Benderly

and Evan Kraft Independent Slovenia Origins. Movements Prospects pp. 7-8.

7 Dejan Djokic, Yugoslavism: Histories of a Failed Idea 1918-1992, p. 84

8 Jill Benderly, Evan Kraft. Independent Slovenia: Origins,

Movements, Prospects 1994 p.13

9 Carole Rogel, In

the Beginning the Slovenes trom the Seventh Century

to 1945, in Jill Benderly and Evan Kraft, Independent

Slovenia: Origins, Movements, Prospects p. 3

10 The Kingdom of

Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was renamed Yugoslavia in 1929 after a troubled

first decade.

11 For the record of

official documentation regarding the formation of SCS see Dr. Orner Ibrahimagic, Politicki Sistem Bosne i

Herzegovine. pp. 157-192.

12 In most parts of

the new kingdom, the cabinet faced near chaotic conditions

-legal-administrative, economic, social and psychological. Prior to unification

there had been six legal units, and despite the early creation ofa special ministry for the purpose of bringing about

equalization of the law and a modicum of legal uniformity, progress was rather

slow. In Alex N. Dragnich, The First Yugoslavia:

Search for a Viable Political System, p. 14.

13 Dr. Mustafa

Imamovic, Historija Drzave

I Provo Bosne I Herzegovine.

p. 296.

14 First peace

agreement was with Austria on September 10, 1919; second was the peace

agreement with Bulgaria on November 27,1919 which enlarged Serbia by two

provinces - Dimitrovgradski and Bosiljgradski;

third peace agreement was with Hungary on June 4, 1920; fourth peace agreement

was signed with Turkey on August 10, 1920. in Dr. Mustafa lmamovic,

Historija Drzave I Prava,

p. 297.

15 Ibid.

16 Alex N. Dragnich, The First Yugoslavia: Search for a Viable

Political System, p.ll.

17 Alexandar Pavkovic, p.92

18 In the late 1980s,

Slovenia, with 8 per cent of the whole population, produced 22 per cent of

Yugoslavia's public revenues, 30 per cent of Yugoslavia's export in general.

See Viktor Meier, Zakaj je Razpadla

Jugoslavija, Ljubljana, 1996 p. 171.

19 The Memorandum of

the Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences (SANU), released in 1986, is a well organized list of complaints and criticisms against

the Yugoslav system as it existed at the time. The main theme of the argument

in the Memorandum is that Serbia was wrongfully taken advantage of and weakened

under 1974 constitution of Yugoslavia, and that as a result, Serbians are the

victims of genocide (in Kosovo) among other things. The Memorandum is written

in such a way that it acts as a call to arms for the Serbian people, and

justifies any actions taken that will insure the security of threatened Serbia.

20 "The Memorandum", cited in B. Covic, ed., Roots of Serbian

Aggression, Zagreb, 1993 p. 324.

21 "The

Memorandum" cited in H. Sarkinovic, Bosnjaci od Nacertanija do Memoranduma, Muslimansko Nacionalno Vijece Sandzaka, Podgorica, 1997, Podgorica, 1997, pp. 287-406

22 Nase Teme, Vol. 33

Nos 1-2, Zagreb, 1989 p. 162.

23 This statement was

part of a speech in defense of the Albanian position on Kosovo by Slovenian

President Milan Kucan which was used by Dusan Mitevic,

Milosevic's man at Radio Television Serbia, to stir Serbian opinion against the

Slovenian leadership. For a detailed account see Death of Yugoslavia.

24 See, I. Urgancic, 'Jugoslavenska "Nacionalisticka Kriza" in Slovenei

v Perspektivi Konea Naeija'. p. 56 and F. Bucar, 'Pravni

ueditev polozaja Slovence kot naroda'.

p. 159 in Nova Revija (1987); Alexandar Pakovic, p. 109.

25 A. Bibic, 'The Emergence of Pluralism in Slovenia,' Communist

and Post-Communist Studies, vol. 26, no. 4 (1993) 370-1. In Alexander Pavkovic, The Fragmentation of Yugoslavia: Nationalism and

wars in the Balkans. p. 109

26 This was the time

when both dissident groups took on a more active role in voicing their agendas.

In early 1988, Mladina boldly 'attacked' the Yugoslav

federation army by exposing its arms sales to impoverished Third World

countries and revealing its corruption activities. That same year, as the paper

was preparing to publish transcripts of military meetings discussing the arrest

of Slovene dissidents, the Yugoslav federal army made an arrest of three of Mladina 's joumaJists and a

Slovene sergeant -major who provided the documents for them. As one of the

arrested individuals was Janez Jansa, prominent

activist of the Alternative movement's peace branch, the movement responded by

founding the Committee for the Defense of Human Rights consisting of dissidents

ftom the Mladina and ftom the Slovenian Society of Writers. Supported by the

Slovene Communist Party, the media and the Roman Catholic church, the committee

organized a widespread campaign of protests against the arrest of the so-called

'Ljubljana four'. The decision to conduct the proceedings in Serbo-Croatian,

which the constitutional court ruled to be constitutional, marked the high

point in the Slovene dissatisfaction. The trial and sentencing prison terms

escalated what was already considered a volatile situation in Slovenia. People

were mobilized by their grievances and started protesting paving a way to a

clear road to independence.

M. Bakic-Hayden and R. M. Hayden. 'Orientalist Variations on the Theme

"Balkans": Symbolic Geography in Recent Yugoslav Cultural Politics',

Slavic Review, vol. 51 no 1 (1992) pp. 1-16.

27 S.P. Ramet,

Nationalism and Federalism in Yugoslavia, 1962-1991, 2nd ed. (Bloomington:

Indiana University Press, 1992) p.211.

28 Alexander Pavkovic, The Fragmentation of Yugoslavia: Nationalism and

wars in the Balkans.p.110

29 S.P. Ramet,

Nationalism and Federalism in Yugoslavia, 1962-1991, 2nd ed. (Bloomington:

Indiana University Press, 1992) p.211.

20 These amendments

as well as constitutional changes by Serbia and other republics were

subsequently declared unconstitutional by the Yugoslav Constitutional Court. R.

M. Hayden, The Beginning of the End of Federal Yugoslavia: The Slovenian

Amendment Crisis of 1989 (Pittsburgh: The Center for Russian and East European

Studies, The Carl Back papers, 1992) pp. 11-20.

21 T. Mastnak, p.312

22 Aleandar Pavkovic, The

Fragmentation of Yugoslavia, p.lll

23 The turnout at the

elections was 93.2 per cent. Dejan Djokic (ed.) Yugoslavism:

Historie~; of a Failed Idea 1918 -1992. p. 97.

24 See The Death of

Yugoslavia, Programme 2 for Jovic's account and

military intelligence film of the crucial meeting.

25 Susan Woodward,

June 27, 2005.

26 J.Jansha, The Making of the Slovenian State 1988-1992 (Ljubljana:Mladinska Knjiga 1994)

pp. 101-113 4

27 Alexandar Pavkovic, The Fragmentation of Yugoslavia, pp. 135-135

28 See B. Bucar 'The

International Recognition of Slovenia' in D. Fink Hafuer

and J. R. Robbins (eds) Making New Nation: The Formation of Slovenia, (Adershot: Darmouth, 1997)

29 For Slovenian

planning and requests for mediation see D. Rupel 'Slovenia's Shift from the

Balkans to Central Europe' in J. Benderly and E.

Kraft (eds.) Independent Slovenia: Origins. Movements. Prospects (London:

Macmillan, 1994) pp. 190-191.

30 Alexandar Pavkovic, The Fragmentation of Yugoslavia, p 137

31 James Gow and

Cathi Carmichael, Slovenia and the Slovenes: A Small State and the New Europe,

p. 177.

32 J. Robbins,

'Epilogue the Attainment of Viability' in Making a New Nation the Formation of

Slovenia, E.287.

33 Christopher

Bennett, Yugoslavia's Bloody Collapse: Causes. Course and Consequences, p. 159.

34 Ruper, op. Cit.

191.

35 The Troika

comprised the past, present and coming foreign ministers of the Presidency of

the European Council of Ministers. In June they were Gianni de Michelis

(Italy), Jacques Poos (Luxebourg) and Hans van den

Broek (the Netherlands).

36 Some authors

claimed that the direct European intervention in the conflict began in May 1991

with the clandestine delivery of several thousand infantry weapons as well as

communications equipment to the Slovenian defense forces trom

an unnamed European country. See J. Jansa, The Making of the Slovenian State

1988-1992 pp. 101-113.

37 Susan Woodward in

Balkan Tragedy argues that the fate of Slovenia and Croatia were already

resolved at Brioni. She pointed out that the meeting which took place paved the

way to eventual recognition of both countries. James Gow in The Triumph of the

Lack of Will points out that at Brioni the troika managed to establish peace in

Sloveni and create conditions for peaceful

negotiations. p. 52.

38 This included its

control over the international borders and the collection of customs duties.

For updates

click homepage here