Negotiations between

the United States and Russia have changed focus in the latter half of the year.

Russia countered the U.S. moves into Eastern and Central Europe with its very public

support for Iran, complicating U.S.-Iranian negotiations over Iraq. This is a

major shift from the July meeting between Russian President Vladimir Putin and

U.S. President George W. Bush in Kennebunkport, Maine, when one of the more

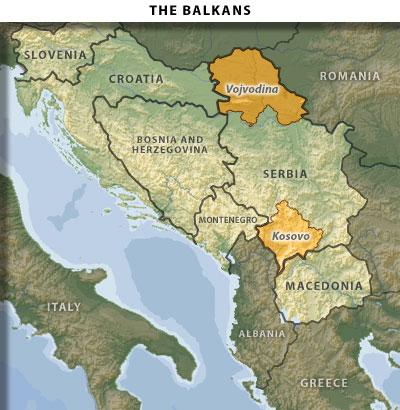

important items on the agenda was Kosovar independence. This issue has been on

the table since 1999, when the United States and its NATO allies, angered over

Serbian behavior in Kosovo, ignored Russian objections and waged a 60-day air

war against Yugoslavia. Then on During a historic trip to Albania on June 9

this year (2007), U.S. President George W. Bush - the first American president

to visit the Balkan country - calling for a final ruling on Kosovo's

independence. The stop was one of many on Bush's tour of Europe following a

tumultuous few days at the G-8 summit in Germany, at which Kosovo was a major

topic of discussion.

Since then, Moscow

has been outraged at the looming possibility of an independent Kosovo - not

because it considers Serbia an ally, but because a successful effort by the

West to impose its will on Serbia against Russian wishes would signal the end

of Russia's influence in Europe. It also would signal that the West believes

Russian objections can be easily swept under the rug. Yet Kosovo is threatening

to declare independence next month, Dec. 10, a reason why we included it in our

research project.

Though neither Russia

nor the United States has mentioned Kosovo much of late, small items in the

Serb and Kosovar media indicate that the issue is still very much alive inside

the negotiations. Talks resumed between Pristina and Belgrade in Vienna this week,

and Pristina went in with the assumption that a decision would be made, given

that Dec. 10 is only six weeks away. But the talks only proved that the U.S.,

EU and Russian troika is staunchly divided. Moreover, they show that the U.S.

and EU positions are fractured. Until this week, the United States and European

Union were unified in their position that Kosovar independence not only was

inevitable but also would be achieved this year. This has always been Kosovo's

trump card against Russian and Serb opposition to independence. However, on

Oct. 29, the United States suddenly proposed a new option of freezing Kosovar

independence for another 12 years - much to Pristina's horror. On top of this,

the next proposal to be considered at the troika meetings with Serbia and

Kosovo is designed by none other than Russia - and of course, it would halt any

moves for Kosovar independence.

Additionally, U.S.

Defense Secretary Robert Gates let it slip during an Oct. 27 press conference

on Afghanistan that the United States is considering pulling its troops from

the NATO coalition in Kosovo (KFOR). These announcements could mean one of two

things: Either the United States simply has too much on its plate and needs to

pull back somewhere, or Kosovo has just become another concession Washington is

willing to give Moscow. As far as the first option, the United States does have

its fingers in many pies with its obligations in Iraq and Afghanistan -- not to

mention its growing concerns over Iran and Russia. In the 1990s, the United

States stepped into the Kosovar crisis when the Europeans could not handle it.

But that was back when the United States was not as busy. Pulling back

diplomatically and/or militarily from Kosovo would leave the issue in the

Europeans' lap, and geographically, they have a greater vested interest in a

resolution in the Balkans.

But the timing of the

announcement seems to point to the second option. The new proposal comes at a

time of critical moves among the United States, Iran and Russia - and as rumors

of U.S. concessions are leaking. Allowing the Europeans to handle the Kosovar

issue pushes the United States out of the Russian line of fire. Also, it can be

added to the tally of things Washington has set aside in order to keep its

balance with Moscow as the game continues. But today we first will proceed with

presenting an in depth case study of Bosnia and Herzegovina, including Croatia,

of which it was a part.

Croatia/Bosnia

Of crucial importance

in the history of Croatia, was when the Dalmatian chieftain Tomislav received

papal blessing from Pope John X in 925 as he assumed the title of first King of

Croatia. In 1102 then, Hungary established its dominance over the region

and its king ruled Croatia, which was however allowed to maintain its own

parliament known as Sabor.1 Its most turbulent period between the fourteenth

and sixteenth centuries however, was marked by the Ottoman invasion. The

Austro-Croatian army managed to defeat the Ottomans. At the end of the

seventeenth century the Austrian Habsburg monarchs assumed the crown of both

Croatia and formed a military frontier known as “Krajina” which was a strip of landstretching around the border between Croatia and

Bosnia. It was settled by Serbian immigrants fleeing from the Ottomans. In

return for some of the privileges they enjoyed in Krajina, Serbs were obliged

to provide military service to the Austro-Hungarian Empire.2 The Habsburg kings

supported the Krajina Serbs in developing their own separate identity as a

community of soldiers and fighters. Krajina served as a buttress against

attempt of Croatia towards independence.3

The period that

marked the beginning of modem Croatian nationalism however began in 1830s.4 It

was mostly young intellectuals and students along with the growing middle class

that led the movement. The main aim of the revivalists was to bring about the emotional

change necessary for developing national pride and to translate those

sentiments into political power.5 The nineteenth century was an important

period in Croatia’s history as it marked the period when the idea of national

independence surfaced. The Bishop of Djakovo, Josip

Juraj Strossmayer established a National Party, which

had as its main aim to reform the Habsburg monarchy through the creation of a

federal state. Strossmayer supported the Yugoslav

idea, building a common South Slavic culture and a “spiritual community”.6 In

1848, the Croatian intelligentsia began to formulate a specific Croatian

identity. Intelligentsia of the well-educated Croats in the Istrian peninsula rediscovered

the importance that the peninsula’s literature played in the cultural identity

of the Croats.7 Unfortunately for the Croats, the Austrian Emperor, recognizing

the possible re-emergence of Hungarian revolution, granted the Ausgleich of

1867 which granted Hungary equal status with Austria in the empire. To further

promote tensions, many parts of Croatia fell under the authority of the

Hungarians. A fierce policy of Magyarization then ensued, since Croatia had

remained loyal to the Austrian Habsburgs during the Revolution of 1848.8 To

escape the danger of Magyarization, two types of Croatian nationalism

developed. One favored loyalty to the Austrian Empire and eventual equality

within the empire. The other supported total autonomy from the empire. For more

than 50 years the nationalist leaders quarreled over which path the developing

nationality should take. These differences would separate the Croats,

preventing a maturation of a national identity, which would unify the majority

of the nation. The initial phase of the Croatian national revival was known as

the Illyrian movement. It had two dimensions: Croatian and Slavic. The first

one stood for national autonomy and for the integration of the Croatian lands.

The Slavic dimension was primarily the result of Croatia’s weak political and

economic position in the empire as well as the outcome of Croatian humanism and

the contemporary Pan-Slavism. The movement was based on the conclusion that all

Slavs were a single nation and should therefore live in one country.9

Some Serbs

interpreted the Illyrian movement as an effort of the Roman Catholic Church

against the Orthodox Church and the Serbian national identity.10 Slovenes

looked at the Illyrian movement with suspicion and perceived it as a threat to

their newly discovered national identity.11 Croatian nationalism was largely

defensive in nature. It began in an era of intensive political struggle with

the Hungarians, and it continued as one of the ways for their self preservation. However, Croatians never stopped hoping

that when the opportune moment arrived they would have their own state. The

First World War, sparked by the assassination of the Austrian Archduke

Ferdinand in Sarajevo by a Bosnian Serb terrorist and the events which took

place over the next four years played a significant role in the development of

the idea of unification of all Slav peoples. The war in a sense presented an

opportune moment for all Slav people to form their own state. In 1915, the

Yugoslav Committee was set up in Paris to lobby the Entente Powers 12 for

support for a new Yugoslav state. The agreement known as the Corfu Declaration

was signed on 20 July 1917.13 In October 1918, during the last days of the war,

a National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs led by Anton Korosec, its President,

and Svetozar Pribicevic as Vice-President, was

founded in Zagreb. On October 29, the Croatian Sabor declared the independence

of the state of Croatia 14 from the Empire.15

In an official

statement Sabor declared that it terminates its current relationship with

Austria-Hungary and that it declares all political, legal and economic

agreements void.16 According to the Sabor resolution also expressed the

intention to join in a unified state of southern Slavs. On November 24,1918 at

the meeting of the Central Committee of the National Council, the only vote

against the decision for immediate unification was that of Stjepan Radic,

leader of the small Croatian People’s Peasant Party. In an emotional speech,

Radic warned against the decision to send the 28-member delegation to Belgrade,

expressed opposition to kingship, and said that Croats would support only a

federal republic. Radic pleaded with the delegates to consider the rights of

the people, who would reject what the delegates were about to do because they

had no authorization to speak in the people’s name.17 Radic demanded a “neutral

peasant republic of Croatia”. And shortly after the unification proclamation,

he came out decisively against union, insisting on Croatia’s right to

self-determination. One day after the proclamation of the Kingdom of Serbs,

Croats and Slovenes on December 2, 1918, his party circulated copies of a

proclamation calling for a movement against the Act of Union. This was almost

immediately followed by demonstrations in which several people lost their

lives.18 However the idea of a unified state did appeal to the intellectual

circles in Zagreb which supported Yugoslavism and

played an active role in the events which led to the creation of the United

Kingdom.19 The new Constitution was proclaimed in 1918 on Vidovdan

(St. Vitus Day), the anniversary of the battle of Kosovo, underlining the

Serbian dominance in the new state.20

An interim national

parliament was created in 1919. In 1934 King Aleksandar was assassinated in

Marseilles by a terrorist from the Macedonian nationalist party VMRO (Internal

Macedonian Revolutionary Organization) acting on behalf of Croatian nationalist

extremists led by Ante Pavelic. As the leader of the Croatian Party of Right,

Pavelic had established a terrorist organization known as the Ustashe Croatian Revolutionary Organization (UHRO)21 in

response to the establishment of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The

party’s aim was the creation of an independent state of Croatia outside

Yugoslavia, free from rule by the Serbian king. The country was then ruled by a

regent, Prince Paul, an anglophile educated in Oxford. He openly supported the

Croatian cause and made propositions to the new leader of the Peasant Party,

Vladko Macek. In the 1938 elections the Croatian Peasants’ Party polled 44 per

cent of the vote. Prince Paul recognized that the integrity of the country was

threatened by the rise of Hitler’s Germany and the collapse of the European

status quo created at Versailles. Fearing that the Croats might side with the

Germans to achieve independence through the dismemberment of Yugoslavia, the

government could no longer resist demands for autonomy for Croatia. Macek and

Dragisa Cvetkovic, the Serbian Prime Minister of Yugoslavia, negotiated a new

constitution, which would provide for a federal state within which a new

province of Croatia, known as the Banovina Hrvatska, would have relative autonomy.22

The agreement was known as Sporazum.23 Macek used the threat of foreign backing

in the hope of forcing concessions from the cabinet and the crown. In an

interview with the New York Times on August 1, 1939, he declared that if

Croatia did not gain autonomy, it would secede from Yugoslavia, even though

this would lead to civil war and Croatia might become a German protectorate.24

The new Constitution

of 20 August 1939 destroyed the integrity of the State and the name Yugoslavia

could not be used but simply “state union”. Additional instructions told

party members that in the central government they should always speak of Banovina

25 of Croatia as simply Croatia and refer to it as free and independent

Croatia.26 The Banovina had its own parliament, the Croatian Sabor and its own

government headed by a Ban appointed by the Sabor rather than the Yugoslav

parliament.27 The Ban, who answered to Prince Paul, and the Sabor headed the

Banovina whose government had eleven departments including internal affairs,

education, judiciary, industry, trade and finances.28 The new Banovina

incorporated Srijem and significant parts of Bosnia

Herzegovina, 29 especially the region of Herzegovina traditionally populated by

Bosnian Croats.30 The decision to form Croatian Banovina was never ratified nor

implemented as its Parliament was dismantled after the start of WorId War Two. According to the plan that was drawn up by

Cvetkovic and Macek, there was supposed to be a Serbian Banovina under the name

of ‘Serbian states’ and formed under the same principle as its Croatian

counterpart incorporating the remainder of Bosnia.

In March 1941

Cvetkovic’s foreign minister signed the Tripartite Pact with Nazi Germany under

the threat of invasion. Almost immediately leading members of the Yugoslav

armed forces, led by Dusan Simovic, staged a coup in Belgrade, with British

support, and exiled Prince Paul to Greece. The coup was inspired by Serbian

antagonism to the compromise that Prince Paul had reached with the Croats, and

by the creation of the Croatian Banovina, as well as a desire to resist the antangelment with the Germans. The coup leaders, who were

pro-Serb, were determined to destroy Prince Pauls’ politics of compromise with

Croatia’s ambitions for autonomy within Yugoslavia, and to remake Yugoslavia

along ethnic lines of the Greater Serbia project. The coup infuriated Hitler

who launched an air attack on Belgrade on April 6, 1941, killing large numbers

of civilians, and causing a wave of refugees to flee into the countryside. The

air assault was followed by a massive invasion of Axis forces and a swift

defeat of the Yugoslav army. In Zagreb, the press and popular opinion blamed

the Serbs for starting a war with Germany. There was little resistance to the

invasion and Macek, the leader of the Peasant party, decided not to oppose the

Germans since many of his supporters were enthusiastic to see the end of the

Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Germans invited Macek

to become the leader of a puppet government, which they sought to establish in

Croatia, but he refused to do so. He did not desire a Croatia that would be

dependent on Axis powers.31 Macek correctly calculated that the Germans would

lose the war, but mistakenly predicted that the Croatian Peasant Party

(Hrvatska Seljacka Stranka

HSS) would be restored to power by the victorious Allies. The devastating

consequence of his decision was that the Italians, who had been hosting the Ustashe rebels, brought the fascist leader Ante Pavelic32

to Zagreb where his collaborator Slavko Kvatemik, had

proclaimed the creation of the Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Drzava Hrvatska – NDH).

NDH which incorporated all of Bosnia and Herzegovina, was only independent in

the eyes of Croats living on its territory. In reality, it was divided among an

Italian zone of influence along the coastal areas, and a German zone covering Zagreb

region, Slavonia and north-eastern Bosnia.33 The origins of the Ustashe34

movement dated to the very roots of the Croatian nation itself. Ustashe thought they represented the very essence of the

Croatian people, religion and history.35 They claimed legitimacy by celebrating

the Croat nation and its history, Roman Catholicism, and an overwhelming hatred

of anything associated with the Serbs. The members of Ustashe

saw themselves as the embodiment of all that Croatia was and should be.36 Ustashe believed that Croatia should exist only for

Catholic Croats.

One obvious obstacle

that stood in the way was over one million Serbs that lived in Croatia.

Accordingly, the Ustashe mission was to correct this

apparent problem by annihilating the Serbs in Croatia. The Ustashe

believed in their ethnic uniqueness and based their policies on the fascist and

Nazi movement in Italy and Germany. They were hostile toward the Serbian

population of Croatia, whom they viewed as allies of the government in

Belgrade. Another testament that NDH was designed as a purely Croatian state is

a clause dealing with defense of the country which states that anyone who

violates the interests of Croatian people will be punished by death.37 There is

no mention in this proclamation of Serbs or any other minorities living on the

territory of NDH.

Following the

assassination of King Aleksandar, Ustashe leaders

went to live in exile in Italy where they were imprisoned or promoted by

Mussolini depending on the interests of Italian foreign policy. When the new

state of Croatia was declared in 1941, and after Macek had refused to

collaborate with the Gennans, the Italians sent the Ustashe emigres back to Zagreb from Italy and Germany to

form a puppet fascist government in Croatia. On 10 April Ante Pavelic came to

Zagreb and led the formation of the first Independent State of Croatia.38

Pavelic took the title of Poglavnik39 (Head) of the state, and became prime

minister and foreign minister. Pavelic was welcomed by about 2,000 sworn Ustashe who have been working underground in the country.

By May of 1941 there were 100,000 sworn Ustashe. This

army of extremists had most of their sympathizers among the less educated

classes, and in some poor regions of the Dinaric Mountains where Serbs and

Croats lived in adjacent settlements. On the day after they had established

their government the Ustashe proclaimed the Zakonska Odredba za Obranu Naroda I Drzave (Legal

Provision of the Defense of the People and the State) the basis for their

system of political terror, which included, the institution of concentration

camps and the mass shooting of hostages. They introduced irregular as well as

regular courts.40 Only one week after the proclamation of the Croatian state, a

law was enacted with its declared purpose: “to defend the people and the

state.” Severe punishment was introduced for all those who in any way offended

“the honor and vital interests of the Croatian people” or who threatened the

existence of the Croatian state.41 The main goal of this law was to provide the

Ustashe with a legal framework broad enough to allow

the encounter with all national “enemies” and revenge against the pre-war

adversaries. Such laws were considered a natural element of the national state

and a necessary precondition for its existence. Serbian Cyrillic alphabet was

forbidden and only the Croatian Latin alphabet was allowed to be used.42 The

right to political participation and citizenship in ISC was reserved

exclusively for Croats. All power was in Ustashe

hands, and the laws and legal system could be interpreted and applied in

whatever way they desired.43

Although there was

some initial enthusiasm for the new government there were resistance movements

in the Serbian areas of the Dalmatian hinterland around Lika and Knin,

organized by the communist-led Partisans who were building up their support in

Croatia.44 Bribery and territorial changes made for political gains on the part

of Croatian politicians were a common practice and an exemplary indicator of

the lack of legitimacy in the Croatian ‘state’. Ante Pavelic, for example,

granted most of the Dalmatian coast to the Italians in return for their support

of the new government. There is evidence that the Ustashe

were indeed controlled by the Italians in the 1930s and by the Germans in the

1940s. Pavelic in his book published in Germany in 1941 titled Die Kroatische Frage (The Croat Question) outlined the conflict

between the Serbs and Croats and suggested that the “Croat Question” was in

fact part of a carefully orchestrated plan on the part of the Germans and

Italians which was unfolding as the Second World War was starting. Pavelic

explained the long history of the Croat struggle for separation from the Serbs

within the framework of a fascist dominated Europe. The Ustashe

believed that the Croatian state had always been a legal entity, even when its

incorporation in another state deprived it of international recognition. For

them the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was illegal, because it had never been accepted

by the majority of the Croatian people through democratic processes – neither

elections, nor referenda. For the Ustashe, the

purification of the nation and the creation of a homogeneous national state

were supreme goals. They pursued this goal by organizing concentration camps

and persecution of not only Serbs but also Jews,45 Gypsies and communists. Ustashe equated sovereignty with ethnic homogeneity. Some

of the examples of this extreme belief were evident in the speeches given in

Croatia at that time. Catholic priest Dionizije Jurcev proclaimed to his followers: “No people other than

Croats may any longer live in this land, because this is Croatian land, and we

will know what to do with anybody who is not willing to get converted. In those

regions yonder, I arrange for everything to be cleared away everything from a

chicken to an old man, and should that be necessary, I shall do so here, too,

since it is not sinful nowadays to kill even a seven year old child, if it is

standing in the way of our Ustashi order.“46

Pavelic and his close

associates prepared their political programme as

emigrants, and planned the most important laws, the form of administration

while organizing the new political and state authorities. They established a

new order which mirrored the contemporary Italian – German model and had the

cult of the nation, the state and the leader as its centre.

Their programme of June 1941 expressed the

totalitarian idea: “In the Ustashe state, created by

the poglavnik and his Ustashe,

people must think like Ustashe, speak like Ustashe, and act like Ustashe. In

a word, the entire life in the NDH must be Ustashe

based.“47 Soon, the Ustashe Corps (Ustaska Vojnica) was formed, in

which only members of the Ustashe movement could

serve. The Muslims of Bosnia and Herzegovina, of whom at that time there were

just over 700,000 were incorporated into the Croatian nation. A special policy

of winning them over was initiated. They were called the “flower of the

Croatian nation” and Bosnia was called the “heart of Croatia”.48

Pavelic promised

Muslims full realization of their material and religious aspirations. Gave them

opportunities to hold high civil and military positions in the state, permitted

Muslim units in the Croatian army. Subsidized their schools, and even made them

a huge mosque in the center of Zagreb.49 In the early summer of 1941 armed

resistance broke out against the Ustashe authorities

and foreign occupation. The main organizers were the Communists, but it was the

Serbian population in central parts of Croatia and in other parts of the NDH

that provided the main support. When Yugoslavia broke up in April 1941 the

Central Committee of the Communist Party of Croatia issued a proclamation

outlining the goals of the national liberation struggle as “liberation of the

country from foreign rule and domination” and the establishment of a “new

democratic Yugoslavia of free and equal peoples, with a free Croatia built on

the basis of self-determination.“50 With these slogans anti-Fascist armed

resistance gradually spread to Croatian regions. In the autumn of 1941

resistance fighters organized themselves into companies, battalions and

detachments called ‘Partisans’.51 In liberated villages and small towns the

partisans established Narodno Oslobodilacki

Odbori (People’s Liberation Committees – NOD) which

as well as providing services behind the lines for the partisan anny also became the civilian authorities.52 This was

accompanied by grave economic troubles. The sudden appearance and steady growth

of political and anned resistance to the Ustashe regime and foreign occupation were clear indicators

of the political disposition of the Croatian and non-Croatian population in the

NDH.53

Since 1928, the

Yugoslav Communist Party had been led by a Croat, Josip Broz Tito. The

Communists in recognition of the importance of the nationality question they

established separate Communist Parties in Croatia and Slovenia, under the

umbrella of the Yugoslav Communist Party. In the early years of the war, in

particular, communications between the various branches of the Communist party

were limited and the Croatian Party began to develop its own programme under the leadership of Andrija Hebrang, a Croat and a member of the Zagreb Party

organization since the 1920s.54 Hebrang realized that

the key to mobilizing support in Croatia was to appeal to the Croatian sense of

independent statehood. He therefore argued in favor of a high degree of

autonomy for the emerging socialist republic. The virtual government

established within the liberated areas in Croatia was known as the Regional

Anti-fascist National Liberation Council of Croatia (Zamaljsko

Antifasisticko Vijece Narodnog Oslobodjenja Hrvatske ZA VNOH). ZA VNOH, placing emphasis on Croatian

sovereignty, appealed to the soldiers in the Croatian militia force known as

the Domobrani (Home Guard) by encouraging them to

join the fight for the freedom and independence of Croatia and its homeland.“55

Towards the end of

the war the Partisans reached an agreement with Ivan Subasic, the former Ban of

Croatia and leader of the royal government in exile, who was also a leading

member of the Croatian Peasant party. An agreement was signed on 16 June 1944 on

the Croatian island of Vis, which was occupied by the British, and where the

partisans had by then set up their headquarters. A further detailed agreement

on 1 November established that the Partisans would take the lead in forming a

new government at the end of the war with the participation of three members of

the government-in-exile.56 At its third session in May 1944, the ZA VNOH was

constituted as the supreme representative legislative and executive body, and

thus the highest body of state authority, in democratic Croatia. This was the

first stage of creating the new federal Croatia in the’ second’ Yugoslavi Josip Broz Tito became Premier in the new

post-war provisional government established in March 1945. In November a

Constitutional Assembly abolished the monarchy and proclaimed the Federal

People’s Republic of Yugoslavia. The new state was established as a federation

of six republics: Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro

and Macedonia.57

In contrast to the

pre-war Banovina, Croatia lost a substantial amount of territory including Srijem to region of Vojvodina, Herzegovina to Bosnia, and

the Bay of Kotor to Montenegro. Part of Istria around Trieste was also disputed

with the Italians. In the 1960s, the development of the post Yugoslav economy

had two significan effects in Croatia. The first was

the development of the tourist industry. This enabled the Croatian hotel

industry to earn a large amount of foreign exchange which had to be surrendered

to the federal authorities in Belgrade. This caused resentment and demands from

Croatian interest groups for a change in policy. Criticism began to emerge that

the federal government in Belgrade was exploiting Croatia, and that Croatia

should be allowed to retain more of her foreign exchange earnings.58 The reform

movement became more serious when it gained the backing of three leading

politicians from the Croatian League of Communists: Miko Tripalo,

Savka Dabcev-Kucar and Pero Pirker. These reform-minded

communists saw an opportunity to achieve a full partnership within the

federation.59 Their campaign developed into a mass movement (the Masovni Pokret – or Maspok) calling for greater autonomy for Croatia within

Yugoslavia. The culmination of the Maspok took place

in autumn 1971 when students at Zagreb and other universities staged a mass

strike in support of the liberals. The Matica

Hrvatska 60 published the Hrvatski Tjednik (Croatian

Weekly) which became the public platform for the non-Communist intellectuals of

the ‘Croatian Spring’.61

They demanded greater

autonomy for Croatia and wanted to retain a greater share of its foreign

currency export earnings. The strike was eventually broken by police action and

by the threat of army intervention.62 This meant as a warning of the possible future

consequences of attempts towards independence of Croatia. Despite the

suppression of the Croatian autonomy movement, Tito quickly implemented

measures that met most of their demands. Croatia was allowed to keep a greater

share of its foreign currency earnings. Constitutional amendments were

introduced in the period between 1967 and 1971, followed by a new and revised

Constitution, which was established in 1974 giving extensive autonomy to the

republics and the autonomous provinces. The new Constitution provided for a

greater degree of self-government of the Croatian Republic, while Serbia was

deprived of its control over the provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. In the 1971

Constitution sovereignty for the Croat leadership was “national”. In both 1971

and the 1974 Constitution, sovereignty was defined within the nomenclature of

“self-management”. In other words the question was not addressed in terms of

the sovereignty of national republics within Yugoslavia but of socialist

entities operating in a framework ofself-management.63 In 1979, economic

difficulties were emerging not just in Croatia but throughout Yugoslavia. The

most serious of these was the abrupt cessation of economic growth while the

social product stagnated at the beginning of the 1980s.64 Tito’s death in 1980

represented the start of not only devastating economic decline but also an

opportune moment for the awakening and full expression of strong nationalistic

feelings which have been suppressed under his presidency. From the moment the

1974 constitution was passed, there was dissatisfaction with it especially

because of the excessive competencies given to the autonomous provinces, which

became practically independent from the republic of Serbia’s jurisdiction.

While Slovenia and Croatia remained neutral with respect to the new

Constitution,65 the Serbs later complained that Kosovo and Vojvodina had been

given all the attributes of states, which they were not. Albanians, worried

that their status may be revoked, responded to Serb’s complaint by staging

demonstrations in the spring of 1981, demanding greater autonomy within the

republic of Serbia, and even calling for their own independent republic. After

the Kosovo demonstrations, views on Serbia’s unsatisfactory position in

Yugoslavia came into the open, being first aired at a session of the Central

Committee of the League of Communists of Serbia at the end of 1981. In November

1984 the Serbian Central Committee again demanded tighter internal integration

of the republic and a better position in the federation. They sensed that

strong processes of disintegration were taking place in Yugoslavia, and for the

first time submitted a ‘Platform for Reintegration’. Although no one publicly

challenged the 1974 Constitution, it was obvious that Serbian nationalist

demands were increasing.66

The period that

followed was marked by a series of amendments to both Serbia’s and Kosovo’s

constitutions forced through by the Milosevic regime. The dissatisfaction of

Slovenia and Croatia was overwhelming and it was clear that crisis was looming

as Yugoslavia embarked on a road to dissolution. In June 1989, Franjo Tudjman

formally established the Croatian Democratic Union (Hrvatska Demokratska Zajednica – HDZ).67

He was a former general in the Partisan army in the Second World War, but later

a nationalist dissident active in the Croatian Spring. Tudjman was a

revisionist historian of European history, and reflected his national policies

and beliefs in his work Nationalism in Contemporary Europe. Tudjman referred to

his interpretation of history and events to glorify the struggle of the Croats

for an independent state.68 His election campaign focused on the natural right

of self-determination for the Croatian people, the end of communist rule, and

placing firmer controls on the Serb minority in Croatia.69

His appeal was for

‘national reconciliation’ between the various elements of Croatian society, in

particular between the left and right wing, between the ideological descendants

of the communist Partisans on the one hand, and the fascist Ustashe

on the other. According to his programme the

privileged position of Serbs in the upper layers of power that threatened to

cause polarization of Croatian society on ethnic lines was to be eliminated.

Tudjman further claimed the Bosnia Muslims were Islamicized

Croats so that the event of the break-up of Yugoslavia. Bosnia Herzegovina

would be incorporated into an independent Croatian state. This expansionistic

idea was justified by his claim of two regions being linked throughout their

histories. He affirmed that only by their working together would they be able

to overcome their common enemy, the Serbs.70 Tudjman blamed the Croatian

economic decline on its unfair economic responsibilities towards Belgrade. Due

to a heavy share of funding from Croatian diasporas, Tudjman was able to secure

victory in the elections. The HDZ gained support from the anti-communist

Croatian diaspora in Canada and the United States. One of Tudjman’s key

supporters was Gojko Susak. A Croat I from Toronto. Who later became Defense

Minister. Other individuals from the Croatian Spring joined the Party. They

included Stipe Mesic.71 a former mayor of Orahovica

in Slavonia and future Prime Minister and President. Who had been dismissed for

his nationalist beliefs in the early 1970s. In May 1990 in the first multiparty

elections in Yugoslavia since the end of WorId War

II. The HDZ won 205 of the 356 seats. Beating the communist party which took 75

seats.72

That same month. The

first meeting of the Sabor took place and Franjo Tudjman was elected President

of the republic, and Stipe Mesic won the seat of the Prime Minister. One of the

first acts of the new Sabor was to introduce amendments to the republic’s own

Constitution which removed the word ‘socialist’ from its name. The new

constitution declared Croatia to be the homeland of the Croatian nation, while

excluding the Serbs and other minorities from their previous position of civic

equality.73 A preliminary section of the constitution, entitled Izvorisne Osnove (“Basic

Sources”) claimed a “thousand year national independence and state continuity

of the Croatian nation” and the “historical right of the Croatian nation to

full state sovereignty” as manifested by a series of states from the Croatian

kingdom of the seventh century through the conclusions of the Joint

Anti-Fascist Council in 1943 and the existence of the Socialist Republic of

Croatia from 1947-1990. After referring to the “inalienable right of the

Croatian nation to self-determination and state sovereignty,” the Republic of

Croatia was “established as the national state of the Croatian nation and the

state of the members of other nations and minorities that live within it.” In

all of these passages, “Croatian nation” (Hrvatski narod)

has an raj rather than political connotation and purposely excluded those not

ethnically Croat. Formally symbolic rather than legally binding since they are

in the preamble to the constitution, these statements are accompanied by the

symbolism of the republic’s ethnically Croat coat of arms and flag (art. 11),74

and the specification that the official language and script of Croatia are “the

Croatian language and Latin script” (art. 12) thus excluding the Serbian dialects

and the Cyrillic alphabet customarily used to write them.75

The 1990 Constitution

further proclaimed the republic’s sovereignty and its right to secede from the

Yugoslav federation. It established the new bicameral parliament with a lower

house known as the House of Representatives and an upper house known as the

House ofCounties.76 A new controversial law controversially allowed ethnic

Croats who lived in Herzegovina region of Bosnia and abroad to apply for

Croatian citizenship. These new citizens were allowed to vote in Croatian

elections even though they were not residing in Croatia.77 Immediately after

coming to power, Tudjman reinstated Sahovnica, a

white and red checkered shield, on the Croatian national flag.78 This shield

had been the traditional sign of the Ustashe and it

was a symbol of the medieval Croat rulers and of Croat history and national

identity. The Sahovnica’s reintroduction on the Croat

flag was interpreted by the Serbs as a clear sign that the Ustashe

had returned and that Serbs were no longer welcome in Croatia.79

Political parties in

Croatia were not able to form an agreement between Serbs and Croats in the

process of gaining independence. The fact that there was no Serb-Croat

coalition as in the pre-First World War tradition of Pribicevic

and Supito, or in the wartime regime of Hebrang, encouraged Croatian separatism and Serb

alienation. Later on, Stipe Mesic was to say that one of the greatest mistakes

of the new Croatian government was its failure to immediately make an alliance

with the Serbian Democratic Party (SDS), which responded by boycotting the

meetings of the Sabor.80 This ‘oversight’ on part of the new government only

exacerbated Serb dissatisfaction. In turn, on 1 July 1990, Milan Babic, deputy

in the SDS, declared a union of local councils in Lika and Northern Dalmatia,

taking the first steps towards creating an autonomous Krajina region.81 A

Serbian National Council was proclaimed at a mass meeting of Serbs in the

village of Serb.82 An unofficial referendum was carried out in the Krajina, and

Milan Babic declared the ‘Autonomous Province of Serb Krajina’ in August

1990.Roadblocks were set up around Knin, and rail traffic was disrupted, making

travel between Zagreb and the Dalmatian coast extremely difficult. The growing

rebellion was spurred on by the activities of agents of Serbia’s secret police,

the SOB, acting under the instructions of Slobodan Milosevic who sought to

protect the Serbs of Croatia and incorporate them into “Greater Serbia”. In

case Croatia was to declare independence, government in Belgrade planned on

incorporating the Serb populated part of Croatia into Serbia. 83

A referendum on

independence for Croatia was held in May 19, 1991 on the question “Do you agree

that the Republic of Croatia as a sovereign and independent state, which

guarantees cultural autonomy and all civil rights to Serbs and members of other

nationalities in Croatia, may enter into an alliance with other republics?” The

referendum was approved by 93 percent of the 83,6 percent of the electorate.

This represented a total of 79 percent.84 Serbs of the rajina

autonomous region boycotted the referendum expressing their desire to join the

republic of Serbia and remain part of Yugoslavia. Croatia declared its

independence on 25 June 1991, with the ‘Proclamation of the Sovereign and

Independent Republic of Croatia’.85 Following intervention by the EU and US

Secretary of State James Baker, the Slovenes and the Croats were persuaded to

postpone their plans for independence for three months to allow for

negotiations to take place. However, almost immediately, the Yugoslav Air

Force, backed up by the JNA, moved in on the breakaway republic of Slovenia.

The JNA “defeated“86 by the Slovenes in a short ten-day conflict agreed to sign

a cease-fire and withdraw. This effectively marked the end of the Yugoslav

state. In fact it later turned out that Milosevic backed up by Boris Jovic and

Veljko Kadijevic as the commander of the JNA, had no

intention of engaging in serious fighting to retain Slovenia within Yugoslavia,

since the republic formed no part of their plans to create a Greater Serbia. It

became known that a deal was struck in January 1991 between Serbia and

Slovenia. Miloseivic signaled to Kucan that the

Slovenes were free to leave Yugoslavia so long as they did not oppose Serbia’s

plans for the rest of country.87 Boris Jovic speaking in the Serb Parliament,

also later claimed that “we the Serbs couldn’t care less if Slovenia left.“89

Croatia was a very

different case from Slovenia. There were significant number of Serbs in the

breakaway Krajina and eastern Slavonia, and Milosevic’s policy was designed to

incorporate these regions into a new Greater Serbian state. To achieve this,

Croatia would have to be broken up, and its armed forces had to be defeated. As

the crisis grew, Tudjman created a government of national unity, which included

his communist adversaries. The two sides were becoming polarized, and both

Serbian and Croatian extremists fed on each other’s fears. On 11 August, the

Sabor announced the creation of the new army, the Croatian National Guard. One

month after that a major offensive was launched by the JNA in eastern Slavonia.

The Domovinski Rat (Homeland War) for Croatian independence

began by the bombing of the Zagreb airport by the Yugoslav air force followed

by offensive operations across Croatia. The UN Security Council imposed an arms

embargo on all the republics of Yugoslavia on September 25.90 The fiercest

battle of the war was fought for the city of Vukovar

in eastern Slavonia. Following the fall of Vukovar,

the JNA moved on towards Osijek. It seemed as if the whole of Croatia would

fall to the far greater strength of the JNA. However, before that could happen,

Milosevic and Tudjman, under pressure from the EU which had convened a peace

conference at The Hague, came to an agreement to end the war. In an emergency

meeting on 3 October 1991 Yugoslav minister of defense, General Kadijevic, Presidents Tudjman and Milosevic and EC

representatives van den Broek and Lord Carrington accepted in principal a peace

plan that took as its starting point confederation and presumed the eventual

independence of all republics that desired it.91 Croatia would be recognized,

the Yugoslav army would withdraw, and the breakaway Serbian regions of the

Krajina and Slavonia would demilitarized and patrolled by the UN

peacekeepers.92 Croatia officially applied to the Community for recognition on December

19, 1991. The cease-fire agreement was brokered on November 23, 1991 and was

finalized on January 2, 1992. It was signed at Sarajevo by military

representatives of Croatia and Yugoslavia. The UN Protection Forces of 14, 000

began to arrive on March 8, 1992.

It is clear that the

Croatian case differs from that of Slovenia which we also

investigated, mostly

in the pronounced Croatian desire for independence throughout its history which

is filled with attempts to achieve autonomy and independence from the European

powers and then from Yugoslavia. Croatia’s decision to join the Kingdom of

Yugoslavia was more a desire to end Austria-Hungary domination than a wish to

be part of the Kingdom. Its opportunity to form its own state came with the

German aggression against Yugoslavia at the start of the Second World War. No

price was too high to be paid for the Croatian elite and politicians who saw an

opportunity in cooperation with the Nazi Germany. The Independent State of

Croatia (Nezavisna Drzava Hrvatskal NDH) was an illegitimate, illegal entity and a

product of the circumstances of the world war. The Ustashe

hoped to use the war circumstances to achieve the national ideal with the help

of Italy, Germany, Austria, and Hungary, the only outside powers that had been

ready to support their struggle. The paradox was that all these countries,

especially Italy, had traditional expansionist demands on Croatian lands. The Ustashe movement was indeed supported by Italy but at a

very high price. According to the Pact of Rome signed on 18 March 1941, in

return for Italian recognition of him as Poglavnik,

Pavelic was compelled to abandon to Italy nearly all Croatian islands, almost

all of Dalmatia and a substantial portion of Rijeka.

Even though Germany

and Italy helped create the Independent State of Croatia, they were never

concerned about the interests of Croatian people nor did they intend to grant

it real independence. Italy was mostly concerned with acquiring Croatian

territory while Germany wanted a satellite in the Balkans which was very far

from the idea of state independence. Croatia never had an independent foreign

policy. In joint operations with the German army the Ustashe

military units were always under German command. German military commanders and

German diplomatic representatives in Zagreb frequently interfered in the

internal affairs of the NDH, even appointing local civil authorities. There

were also tensions and clashes between the Italian forces and the Ustashe. Furthermore, neither the Italian nor the German

military and political circles believed that their Croatian ally was capable of

surviving on its own. With the end of the Second World War and capitulation of

Germany, NDH disappeared. However, the idea of an independent Croatia

persisted. After joining the second Yugoslavia under Josip Broz Tito, Croatia

had its own republic and enjoyed equal rights with the other republics. Croatia

always had desires and demands for independence. Tito’s death and the fall of communism

presented another opportune moment for Croatia to seek greater freedoms and

more autonomy for its republic. Political circumstances at the time included

the election of Slobodan Milosevic in Serbia who revoked the Constitution of

1974 which gave the right to self-determination to all ‘narodi’

(people). The election of Franjo Tudjman in Croatia who was extremely

nationalistic and wanted independence for Croatia contributed to the

dissolution of Yugoslavia and helped Croatia gain independence. Throughout his

presidency, Tudjman tried to mobilize support among Croatian people as well as

from other European states especially Germany and Austria. He often referred to

struggles of Croatian people to achieve independence and have their own state.

He took pride that Croatia had had its own independent state, the NDH. Through

the NDH inclusion of Bosnia and Herzegovina he was determined to create a

‘Greater Croatia’ which would include at least Herzegovina, mostly populated by

Croatians, if not the whole of Bosnia. This case study clearly shows that

historical memories of statehood, legitimate or illegitimate, play an important

part in mobilizing people and re-awakening old nationalistic feelings. This is

why Tudjman was able to establish himself as a strong leader fighting for the

self-determination of all Croats. Without the support of all Croatians, who at

the referendum expressed their desire for a Croatian state, it is questionable

whether Croatia would have been able to declare independence and gain recognition

by other states. Case of Bosnia Bosnian history is mostly characterized by

foreign conquests interspersed with periods of independence. There were two

forms of state organization in medieval Bosnia: banovina until 1377 and kingdom

until 1463. Bosnia was an independent state during both forms, headed by a Ban

and a King. Medieval Bosnian state functioned in accordance with the standards

of customary law and state protocols typical of the time.

Bosnian law was not

encoded in a statue. However, Bosnian customary law was binding for leaders and

nobility.93 If they took the throne, the first thing to do was to issue a

charter confirming all the rights established by their predecessors. Written

sources include international contracts, landowners’ charters and inscription

on tombstones.94 Historic sources confirm the existence of “a state apparatus

in Bosnia” during the rule of Ban Kulin (1180-1204), as well as the existence

of “a court chamber”, “very high income”, and “a considerable cultural

development” of the country.95 The famous charter for the people of Dubrovnik

from 1189 confirmed Bosnia as an independent state guaranteeing freedom of

passage and trade for merchants from Dubrovnik in its territory. During the

ban’s rule in Bosnia, the best sources to confirm Bosnia’s status as that of an

independent state rather than a dominion were the Pope’s letters to rulers and

neighboring countries as well as charters issued by the bans of Bosnia to merchants.96

In 1376, King Tvrtko

I (1353-1434) came to power and aided by the Ottoman Turks, he expanded his

rule into western Serbia and took most of the Adriatic coast. With respect to

his political plans, he aimed to develop Bosnia into an ethnically united entity.97

At the time of Tvrtko, there were two legal and political bodies in Bosnia: the

court and the rule or state council with equal powers in decision-making in

legal matters.98 After supporting the uprising of Croatian and Dalmatian

leaders against the Hungarian Empire in 1389, Tvrtko became the ruler of

Croatia and Dalmatia in 1390. In 1414. There was a military and political

disruption of the balance of power created by the Ottoman Turks, who proclaimed

Tvrtko II as rightful King of Bosnia, and sent a large military force to

Bosnia. The Hungarian anny was defeated and the

Ottoman Empire would have an influence rivaling that of Hungary over Bosnian

affairs.99 Tvrtko II held on to power until his death in 1443 while Stephen Vukcic, the lord of Hum, continued to obtain more power. At

first Viukcic refused to recognize Tvrtko’s

successor, Stephen Tomas, and several years of civil war followed. To emphasize

his own independent status, Vukcic gave himself a new

title in 1448 as the ‘Herzeg (Duke) of Hum and the Coast’ which he later

changed to ‘Herceg (Duke) of Sava’. In the early 1450s he faced a war against

Ragusa and a civil war with his eldest son. The conflict in the family only

intensified and in 1462 the son sought help from the Turks and encouraged them

to include Herzegovina, along with Bosnia, in their plans for a massive assault

in 1463.100

That same year

Turkish army under Mehmet II marched into Bosnia which was defeated rather

easily due to internal disagreements over religion.101 During the Turkish rule,

Bosnia went through the process of islamization.102 In 1580, the Ottomans

decided to make Bosnia into one elayet or province,

which meant that it would be ruled by the highest rank of pasha or beglerbeg, the lord of lords. The Bosnian entity included

the whole of modem Bosnia and Herzegovina, plus some neighboring parts of

Slavonia. Croatia. Dalmatia and Serbia. The elayet

was to serve as a barrier against further expansion and defense against Austria

and Venice. During the Ottoman rule Bosnia enjoyed a special status as a

distinct entity. While the old kingdom of Serbia was to remain divided into a

number of smaller units. Bosnia retained a unique status for the rest of the

Ottoman period. The main authorities for the Ottoman legal system were the

sharia law and the state (sultan) law or kanun which was imposed in Bosnia.103

State laws were published in special orders (ferman)

and later in characters hatishari. State law

regulated relations not covered or partly covered by sharia law. Such as

administration. Hierarchy and taxes. Some of the weaknesses that were apparent

in the structure of the Ottoman Empire aided the growth of power and autonomy

in the hands of local semi-independent Muslim lords.104 This period was

characterized by frequent clashes among different religions. However this was

not the main reason for the fall of Ottoman rule and Austrian intervention. In

the summer of 1875 there was a growing discontent among the Christian peasants

in Herzegovina. Who had to pay very high taxes.105 The basic cause of

dissatisfaction was agrarian but also due to the fact that the Orthodox population

publicly declared its loyalty to the Serbian state.106 The Bosnian governor

assembled an army in Herzegovina. Which acted with brutality during the autumn

and winter of 1875-6. By mid-1876. The local crisis became international and in

July, Serbia and Montenegro declared war on the Ottoman Empire.107

However it was not

until Russia became involved and declared war on the Ottoman Empire in 1877

that the Turks perceived the threat seriously. There had already been much

negotiation between the Russians and the Austrians to carve out the Balkan

lands. By early 1878 with Russian troops approaching Istanbul, Russia dictated

a settlement under the Treaty of San Stefano. Under the Treaty, Bosnia was to

remain Ottoman territory, but various reforms were introduced.108 Bosnia was

provided with more freedoms and was able to have its own administration,

however it did not possess full sovereignty over its territory and was still

under the Ottoman Empire. Finally the question of whether to assign Bosnia to

Austria or Hungary was resolved by making it a Crown land, which meant that it

was ruled by neither and at the same time by both.109

From the legal

perspective, the Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina can be divided

into two periods. The first one was from 1878 to the 1908 annexation, when its

rule was interim, under the mandate of the international community, while the

sultan still held formal sovereignty over Bosnia. The second lasted from 1908

until 1918 when Bosnia was annexed and transformed into a colony of

Austro-Hungarian Empire, with its full sovereignty held by the Empire, but with

certain forms of political authority exercised with participation of the local

populations under the control and authorization of the central authority in

Yienna.110 Even though significant elements of military rule and limited civil

rights were present throughout Austrian rule, Bosnia and Herzegovina was never

an integral part of the Austro-Hungarian state structure. When the great powers

of Europe met at the Congress of Berlin in July 1878 to rewrite the settlement

made at San Stefano, they were concerned about Russia’s influence in the Balkans

and its drive to the Mediterranean. The main legal documents determining the

status of Bosnia and Herzegovina after 1878 were Article XXY111 of the Berlin

Treaty and the Istanbul Convention of 1879. The Congress of Berlin announced

that Bosnia and Herzegovina, while still in theory under Ottoman suzerainty,

would be occupied and administered by Austria-Hungary.112

This was exemplary of

the way the fate of small countries was decided.

The Dual Monarchy did not bring the promised changes to Bosnia.113 The main

effect of the annexation on Bosnia’s internal life was beneficial. The man in

charge of Bosnia from 1882 to 1903 was uncrowned king Benjamin Kallay, an

Austro-Hungarian diplomat and a historian and author of History of Serbian

People.114 He was put to power with a mission to protect Austro-Hungarian

interests. Interestingly in 1883 a Croatian Ban was chosen who was also a

Hungarian, Lord Kuen. Both of them ruled Bosnia and Croatia with a clear goal

to prevent any attempt on the part of Serbia and Croatia to enter into a

coalition against Hungary.115

The legal position of

Bosnia and Herzegovina after the occupation was an anomaly in comparison with

the then legal norm. The sultan was the legitimate sovereign ruler but the real

power rested with the Austro-Hungarians. This made the position of Bosnia rather

unclear. Theoretically the sultan held sovereignty, but in reality it was a

legal illusion with no significance in actions. On the other hand Bosnia and

Herzegovina was not an integral part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but rather

an annexed territory, thanks to the will of Europe and the agreement by

Turkey.116 The Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina was limited by

three factors arising from the Berlin Treaty: I) objectives of the European

mandate to introduce peace and order; 2) continuous sovereignty of the Ottoman

Empire in Bosnia, obliging the Austro-Hungarian administration to submit all

its laws to the sultan for approval; 3) provisions of the basic international

contracts, showing that the administration was interim. However since the real

intentions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire were to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina

permanently as a strategic access to Dalmatia and Istria, with an intention of

further expansion and gaining access to the sea, it was not possible to

reconcile the sultan’s sovereign rights in Bosnia and historical realities. The

Austro-Hungarian Empire held only the right to internal sovereignty in Bosnia

and Hezegovina.117

As the Ottomans began

to weaken and withdraw from Central Europe, the Habsburg Monarchy also began to

weaken, since there was no longer a need to gather different countries to fight

the Ottoman threat. The Monarchy’s economic policy in Bosnia was colonial.

After the 1908 annexation, Bosnia formally became an Austro Hungarian colony,

since that was the end of the European mandate, and the sultan sold his

sovereignty to the Austro-Hungarian Empire for two and a half pounds sterling,

thus extending the legitimacy of its rule in Bosnia.118 Since 1910 when the

emperor sanctioned the constitution of Bosnia, laws proposed by the newly

established Bosnian Parliament within their competence started to appear as new

legal authorities. 119

By the spring of 1913

relations between Austria-Hungary and Serbia were extremely tense. Serbia’s

conquests had already almost doubled the size of its territories.

Austria-Hungary knew that if Serbia acquired Albanian coastland that it would

pose a strategic threat to the Austro-Hungarians in the Adriatic.120 The

assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Habsburg throne, ignited

the First World War after Austria-Hungary declared a war on Serbia.121 Muslims

formed a powerful organization under the name of “Yugoslav Muslim Organization

founded in Sarajevo in February 1919.122 Dr. Mehmed Spaho123, a savvy

politician argued that Bosnia should seek to preserve its identity as an

autonomous unit within the Yugoslav State,124, Military defeats of the Axis

Forces allowed political parties and groups to publish their memoranda in

Zagreb on September 1918 stating that they no longer recognized the royal

Austro-Hungarian rule, and denying its right to represent them at peace

negotiations. The National Council of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was

established on October 6 while the exclusion of South Slavic lands from the

Austro-Hungarian Empire and their declaration of independence took place on

October 29-1918.125 Establishment of the National Council of Serbs, Croats and

Slovenes- and establishment of the national governments of Bosnia and

Herzegovina, Slovenia, Dalmatia and Croatia, was accompanied by the creation of

a new State of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, covering the territory of South

Slavic lands previously under the Austro-Hungarian rule. The Yugoslav Communist

Party rejected any idea that a set of people defined by their religion could

have a political or national identity.126 In 1936 a Communist intellectual- the

Slovene Edvard Kardelj, wrote “We cannot speak of

Muslims as a nation, but ...as a special ethnic group.”S6S An ‘open letter’

written by Communists in Bosnia in 1939 said that the Muslims had always been a

separate entity (posebna cjelina).127

In March 1941 a young activist, Alija Izetbegovic, and his supporters tried to

found a young Muslims’ Association and to register it on basis of the

regulations in force. The organization was to represent an opposition to

fascism and communism. Its official registration was interrupted by the

invasion of the Germans. As Izetbegovic recalls, after the war, the

organization continued its activities which imprisoned him for three years.

After the start of

the Second World War, on 6 April 1941 the German forces invaded Yugoslavia. In

September 1943, after Italy surrendered and the victory of allied forces became

clear, preparations were launched for the establishment of central authority in

Bosnia and Herzegovina. This took place on November 25, 1943 as the State’s

Anti-Fascist Council of People’s Liberation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Zemaljsko Anti-Fasisticko Vece Bosne I Herzegovine, ZA VNOBIH)

held its first session. This date was considered the date of renewal of

Bosnia’s statehood and establishment of the new Bosnian state on principles of

democracy and respect for human and civil rightS.128 The political basis for

the renewal of Bosnia’s statehood was mass determination of all three peoples

of Bosnia in favor of political autonomy of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the

democratic and federal Yugoslavia as a separate federal unit. The historical

basis was the medieval Bosnian state and the existence of a single Bosnian

nation which preserved an awareness of its political and cultural identity and

its statehood with political particularities preserved by generations

ofBosnians.129 At its Second Session on November 29, 1943, The Anti-Fascist

Council of People’s Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ) issued a Decision on

establishment of Yugoslavia following a federal principle determining the

position of ZA VNOBIH as the holder of legal and state functions of the federal

unit of Bosnia and Herzegovina.130 The Partisans liberated Sarajevo on 6 April 1945

and within a few weeks the whole territory of Bosnia was under their full

control. A ‘Peoples Government’ for Bosnia was appointed on 28 April and

instead of being incorporated into Croatia (the Ustasha

solution) or absorbed into Serbia (the Cetnik plan),

Muslims were offered a federal solution in which Bosnia would continue to exist

as an equal entity within Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav Federal Constitution

proclaimed in January 1946 in which it proclaimed that Yugoslavia would

maintain the freedom of belief and the separation of Church and state. The

conditions of religious life in Yugoslavia did improve after 1954, when a new

law was passed guaranteeing freedom of religion while placing the Churches

under direct state control.

In Bosnia-Herzegovina

Muslim national ideologies developed in two different forms. One was an

officially sanctioned non-religious ideology; the other was a pan Islamist

national ideology. The former explained the recognition of the Muslim nation

as the sixth constituent nation in Yugoslavia in 1968 and the latter

continued the tradition of the religious and political movement Young Muslims (Mladi Muslimani) formed in March 1941 in Sarajevo.131

According to the officially sanctioned ideology, the Muslims affirmed their

socio-ethnic identity through “spiritual traditions and new spiritual,

literary, political and cultural features.“132 The process of affirmation

culminated in communist Yugoslavia with the recognition of Muslims, first

through the introduction, in 1948, of the census category of’ Muslims of

undeclared nationality’, which was transformed into the 1971 census category of

‘Muslims’ under the ‘stated nationality’ rubric. Without the support of the

Yugoslav Communist Party, the official account implied, the Muslims of

Yugoslavia would not have achieved either nationhood or the recognition.133

The pan-Islamist

version of Muslim nationalism regarded Islam as the essence of Muslim national

and political identity. From 1941 the Islamic ideology emphasized the education

of Muslims in the correct Islamic spirit, the creation of a true Islamic society

and the liberation and unification of the Islamic world. While the communist

authorities were able to suppress the organization in the late 1940s by

imprisoning and even executing some of its members, Alija Izetbegovic134

emerged in the late 1960s leading a discussion group consisting mainly of

students of Muslim medresas or seminaries

(theological schools). Izetbegovic wrote a book Islam Between East and West

(Islam Izmedju Istoka I Zapada)

which dealt with finding a place for Islam between East and West. Even though

he wrote the book before his imprisonment in 1946. Manuscript remained hidden

for over 20 years. In 1984 while he was serving his prison sentence. The book

was issued by an American publisher. 135

At the First Party

Congress after the end of the war it was stated that: “Bosnia cannot be divided

between Serbia and Croatia. Not only because Serbs and Croats live mixed

together on the whole territory but because the territory is inhabited by

Muslims who have not yet decided on their national identity136 Historically.

Muslim affiliation and association with Serb or Croat was a reflection of the

political life in Bosnia at the time. It was clear though that Muslims were not

prepared to give up their nationality.137

In spring of 1965

during the Fourth Congress of the League of Communists of Bosnia-Herzegovina,

the Muslim population was given the right to national self determinations138

providing them with a nation as well as a religious form of identity. In 1970

Alija Izetbegovic wrote and circulated a short Treatise entitled “The Islamic

Declaration: A programme of the Islamisation

of Muslims and Muslim peoples”. 139 This program had as a goal liberation of

the Muslim peoples from communist and capitalist influence through a revival of

an authentic Islamic consciousness. The Declaration promoted the idea that only

Islam can reawaken the imagination of the Muslim masses and enable them to

engage in determining their own history.140 The Treatise condemned

authoritarian regimes, proposed more expenditure on education and advocated a

new position for women, non-violence and the rights of minorities. Islam was at

the heart of the solution as it offered a comprehensive and distinct model of

individual, social and political life. The program identified three

‘republican’ principles of political order that were of utmost importance: the

electability of the head of state, the accountability of the head of state to

the people and the obligation of solving communally general and social

issues.141

The attainment of the

Islamic order, according to the program, was considered to be a sacred goal and

could not be overridden by any vote. This meant that while the ‘republican’

principles were not applicable in an Islamic state, the ultimate goal of establishing

such a state was not subject to a democratic procedure but rather the

institution of an Islamic state was a divinely proclaimed historical goal.

Izetbegovic argued that an Islamic movement can take over political power only

when it is morally and numerically sufficiently strong not only to overthrow

the existing non-Islamic authority but also to build a new Islamic one.142

Since Islam is a supranational religion, an Islamic state would not be a

national state. Yet it is to be established in any country in which Muslims

form a majority.143 In 1970 in Bosnia Herzegovina Muslims formed a relative but

not an absolute majority of slightly less than 40 per cent of the population.

At that time two distinct trends developed, one was a movement of secular ‘Muslim

nationalism’ and the other was a separate revival of Islamic religious

belief.144 Izetbegovic’s programme made a successful

connection between Muslim national identity and politics in a rather simple

way. He argued that their Muslim religion defined their national identity and

in that also determined their political preferences. A Muslim’s true allegiance

was to an Islamic movement, which aimed at the affirmation of Muslim religious

and moral conceptions in all aspects of life including politics. The year 1989,

two years after Izetbegovic’s release from prison, marked the beginning of the

Islamic movement. The main goals of the Izetbegovic’s Party of Democratic

Action (Stranka Demokratske

Akcije – SDA) which won the elections in the

Parliament and enabled Izetbegovic to be the elected President of the

republic’s collective presidency, were centered around the spiritual

regeneration of the Muslim nation, its political and social organization and

the takeover of positions of power in all Muslim populated areas.146 Tudjman

made one last attempt to sidetrade Izetbegovic’ s

agenda and incorporate Muslims into Croatia. Izetbegovic in his autobiography

recalled meeting Franjo Tudjman who tried to educate Izetbegovic by saying:

“Mr. Izetbegovic, don’t create some Muslim party, it’s quite wrong, for the

Croats and the Muslims in Bosnia and Herzegovina are one people.147 The Muslims

are Croats and that’s what they feel themselves to be”. Izetbegovic replied

that Tudjman was fooling himself and that the Muslims felt themselves to be

Muslims, who liked and respected the Croats but were not Croats.148

Negotiations between the republics and Serbia broke down in early 1991. On

December 20, 1991 the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina requested

recognition for the CommWlity. On February 28 and

March 1, 1992, a vote was held which the Serbian Democratic Party (SDS) under

Radovan Kardzic boycotted. In an almost unanimous

decision by the 66 percent of the electorate who voted, the republic chose to

separate from Yugoslavia.149 In a SDS plebiscite held before this official

referendum about 90% of the Serbs agreed to remain within the nation.150 On

April 7, 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina was internationally recognized as

politically independent and sovereign state.

Conclusion

Bosnia and

Herzegovina has a Wlique and rich history mostly

characterized by conquest and annexations by foreign Empires. In the period

when it was ruled by a Ban and then a King, Bosnia and Herzegovina was an

independent entity. Other than those two medieval periods its fate was determined

initially by Empires and then European powers. Bosnia and Herzegovina often fOWld itself and its future in the hands of either

Austria-Hungary or the Ottoman Empire. It rarely had a voice or an opportunity

to express its desires with respect to the nature of its political system. The

Yugoslav Communist Party rejected any idea of that a set of people defined by

their religion could have a political or national identity. Therefore Muslims

were always viewed as only a religious group without any prospects of existing

within their own state. During the existence of the Independent State of

Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina was incorporated into the territory of NDH.

Alija Izetbegovic played a crucial role in promoting the idea of an Islamic

Bosnian state. He believed that the attainment of the Islamic order was the

ultimate, sacred goal of all Bosnians. The main problem was that Bosnia and

Herzegovina was not a mono(ethnic) state. The Serbs living in Bosnia were

Orthodox and owed their allegiance to Belgrade, while Croats were of Roman

Catholic faith and they looked up to Zagreb. Neither Croats nor Serbs would

have ever agreed to live in an Islamic, Muslim state and owe allegiance to such

a Bosnian Government. Both Belgrade and Zagreb have over the years tried to

incorporate Muslims into their states and have even tried to persuade Muslims

that they were historically Serbs or Croats. This is the main reason why the

Bosnian statehood was so difficult to achieve, why it caused so many human

lives to be divided and why as we can see from the recent resignation of its Serbian Prime Minister, remains divided.

1 The medieval Sabor

is held to have continued the tradition of Croat statehood by freely electing

kings other than the rulers of Hungary. The thousand year long history of the

Sabor is within this myth portrayed as a protracted political struggle for the

preservation of old historical rights of the Croatian state against the

encroachments of the Austrian Hapsburgs and later, the Hungarian parliament -

both of which were aimed at assimilating Croats and Croatian lands. This

protracted struggle, according to this myth, continued in the Yugoslav state in

which the Serbs, like the Austrians and Hungarians, denied the Croats their

distinct national identity, as well as sovereignty and political independence.

The ultimate goal of this mythical struggle is clearly a sovereign and

independent Croatian state, the very state which was created in 1991 by

Croatia's disassociation from the Yugoslav federation. In Alexandar Pavkovic, The Fragmentation of Yugoslavia, p.8.

2 The Krajina region

was established as a military region or a buffer zone and the Serbian

population enjoyed some special privileges. For example, they were able to have

their social organization called zadruga, their orthodox religious institutions

and most importantly they remained independent from the Croatian feudal system.

3 William Bartlett,

Croatia: Between Europe and the Balkans, p.8.