By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

The search for Nextpolis

Yesterday the highly

anticipated COP26 climate change summit began in the Scottish city of Glasgow. Delegates

from about 200 countries will announce how they will cut emissions by 2030 and

help the planet.

With world warming

because of fossil fuel emissions caused by humans, scientists warn that urgent

action is needed to avoid a climate catastrophe.

A previously unnamed

glacier in West Antarctica is to be called Glasgow Glacier to mark the Scottish

city's hosting of the COP26 climate meeting:

Speaking to reporters

on the way to Rome on Friday, the British PM Boris Johnson used

the example of

the Roman empire’s collapse to highlight what he said was the possibility of

runaway climate change bringing a decline in civilization.

Questioned about the

stakes for Cop26 in Rome, where he was interviewed next to the

Coliseum, Johnson reiterated his warnings about the consequences for the globe.

“If you increase the temperatures

of the planet by four degrees or more, as they are predicted to do

remorselessly, you’ll have seen the graphs, then you produce these very

difficult geopolitical events,” he told Channel 4 News.

“You produce

shortages, you produce desertification, habitat loss, movements, contests for

water, for food, huge movements of peoples. Those are things that are going to

be politically very, very difficult to control.

“When the Roman

Empire fell, it was large as a result of uncontrolled immigration. The empire

could no longer control its borders, people came in from the east, all over the

place, and we went into a dark age, Europe went into a dark age that lasted a

very long time. The point of that is to say it can happen again. People should

not be so conceited as to imagine that history is a one-way ratchet.

“Unless you can make

sure next week at Cop in Glasgow that we keep alive this prospect of

restricting the growth in the temperature of the planet then we really face a

real problem for humanity.”

Johnson has faced

criticism this week for his own inaction over tackling emissions, with

Wednesday’s autumn budget again froze fuel duty, and cut levies on

shorter, domestic flights,

but he arrived in Rome bearing a blunt message for fellow G20 leaders.

In Rome, Johnson will

hold bilateral talks with Scott Morrison, the Australian prime minister, whose

own record on reducing emissions has been

heavily criticised, as well as Canada’s Justin Trudeau and Italy’s Mario

Draghi.

Also attending this

meeting will be the French president, Emmanuel Macron, and the German

chancellor, Angela Merkel, who is expected to bring along her likely successor,

Olaf Scholz, currently the finance minister.

The search for Nextpolis

Thus many, especially this past year, wondered where

to move.

During the pandemic

spring of 2020, our Mesopotamian instincts

refreshed as naturally as riding a bicycle. Australia and New Zealand,

Switzerland and Austria, Finland and Estonia, pairs of like-minded neighbors

with small populations reopened borders exclusively to each other. “Green

lanes” and “immunity bubbles” kicked in, signifying how trust in each other’s

health systems mattered more than centuries of inter-state diplomatic

conventions. The US passport was suddenly welcome in just 30 countries instead

of the usual 150.

The planned site for Necropolis:

Nobody wants a

trade-off between health and wealth. Our vague loyalty to the nation pales in

comparison to our visceral desire to be ensconced inside a green zone. Well-governed

territories would instead connect than be chained to weak links next door.

Indeed, most striking was the behavior of states and provinces within countries

that had no legal right to close internal borders. Hawaii sought to reopen

tourism for Australians and Japanese, but not fellow Americans. Police in Rhode

Island searched neighborhoods for New York license plates; even fellow New

Yorkers in the Hamptons suspected wealthy refugees from New York City of

unfairly plundering their grocery stores. As Scotland brought Covid under

control, it had no interest in letting in undisciplined compatriots from

England.

Anyone who can afford

to is moving away from red zones and into green zones, places with robust virus

testing and vaccination programs. Within the US, that means ditching states

where armed militias occupy capitol buildings to prevent lockdowns while anti-vaxxers

and other “Covidiots” run amok. More broadly, green zones tend to be countries

where politics doesn’t interfere with science and where technology is

aggressively being applied to public health, such as South Korea. Canada’s BlueDot system integrates medical records, geolocated web

search metadata, and mobile phone patterns to warn of virus outbreaks. Swedes

have begun having RFID-tagged chips inserted under their skin that can affirm

their health status. AI now scans health records in China, Singapore, and

elsewhere, and free screenings anticipate the potential onset of cancer and

other conditions. Next, we might see governments proactively offer treatments

using genomics and synthetic biology.

No doubt, public

health will become a significant priority in countries that failed the Covid

test, much as after the Black Death, European societies introduced sewers and

paved roads. But why gamble with your life when life is no longer short?

Indeed, today’s mobile class is looking for “blue zones” that combine

preventive measures and pro-longevity interventions. Places such as Sardinia in

Italy and Okinawa in Japan have earned the blue zone moniker for their

combination of the new environment, organic diet, regular exercise, and strong

community bonds that have propelled locals to the most extended lifespans of

any place on Earth. Humanity would be better off with the blue zone diet of

vegetables, grains, seeds, fruits, nuts, beans, and fish. Longer biological

lifespans could elevate people’s desire to live in places free of arbitrary

violence. Since America is the only rich country with frequent mass shootings,

talented people with a healthy sense of self-preservation will either continue

to raise their security walls or move to more trustworthy communities. In 2019,

San Francisco labeled the NRA a “domestic terrorist organization,” but now that

guns can be 3D-printed, sensible locales will have to monitor those

technologies as well. At the intersection of green zones and blue zones, one

finds societies that have affordable housing and wage protections and female

leaders and community policing.1

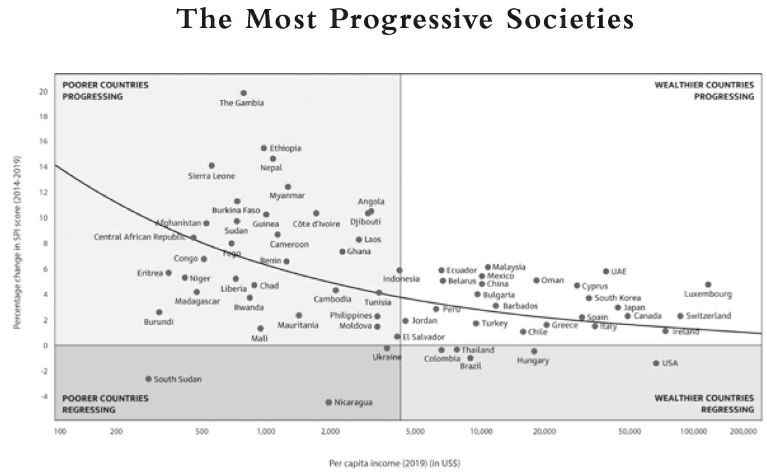

This is a reminder

that people don’t plan their next moves searching for high GDP growth. GDP as a

measure of welfare is the statistical equivalent of gold: It’s only valuable if

people believe in it. Instead, today’s youth are more inclined to put their

faith in sustainable economies, diverse and inclusive societies, and a culture

of rights and wellness. There is an arms race underway to rank countries

according to their socioeconomic inclusion and environmental sustainability

balance. Comparing countries by their GDP versus their rank in the recently

launched Social Progress Index (SPI) is startling. The US, for example, is

wealthier per capita than all but a few small European tax-havens. But given

its poor healthcare, violence, and inequality, it ranks only twenty-sixth in

the SPI. The top tier of SPI countries is made up of the usual suspects in

northern Europe and Switzerland, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand, and large

countries such as Germany, Japan, Canada, and France. Even amid Europe’s low-growth

trajectory, wealth tempered by fairness suggests more excellent social

stability.

Heliogen technology

Canadian, European,

and Australian cities have made the most significant strides toward alternative

and renewable energy such as solar, wind, and nuclear power. No country is

decarbonizing faster than France, which has invited a multinational consortium

to construct the world’s most powerful fusion reactor. Cold fusion technology

has the support of Google and Japan’s Mitsubishi and Bill

Gates, who also backs Heliogen. This concentrated

solar technology could provide enough power even for industrial cement making.

(Companies such as Carbon Cure also inject carbon captured from cement making

back into the cement.) Hydrogen power can already replace coal and gas for steel

making and energy extraction (two other emissions-intensive sectors). Japan is

building two dozen new coal-fired power plants to compensate for its closing of

nuclear plants after the Fukushima disaster. Still, it’s also importing

compressed liquid hydrogen from Australia in a bid to become the world’s clean

energy leader. South Korea is well on its way to having multiple cities fueled

by hydrogen for heating, cooling, and electricity. Fusion, hydrogen, solar, and

wind power can also be used to cool our data centers, the fastest-growing

source of emissions. A city of any size should be able to power itself.

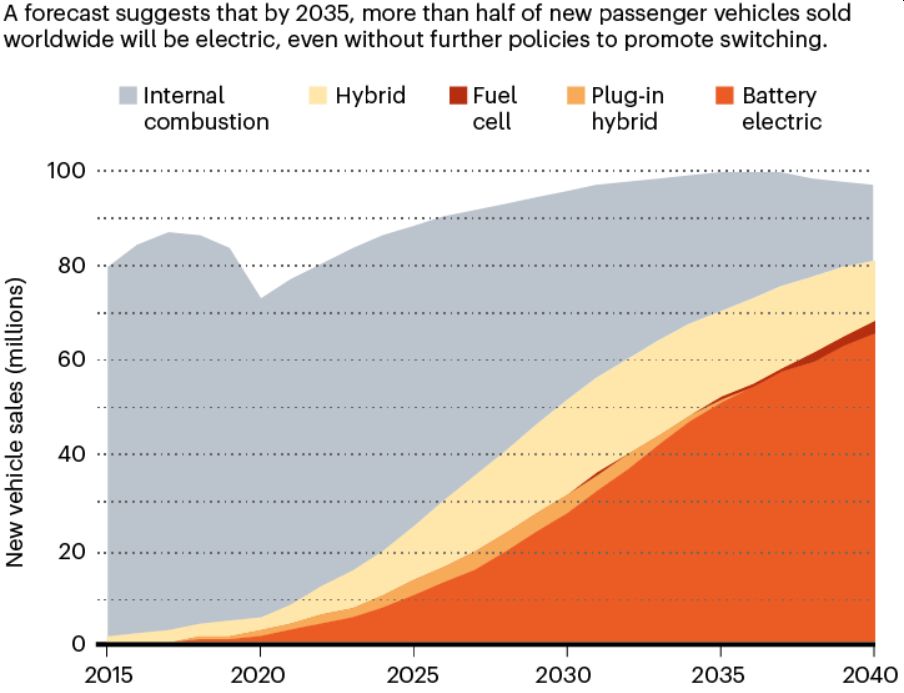

This means that our

mobility within and between cities should have a far smaller environmental

footprint. Thanks to Tesla, BYD in China, and the many European and Japanese

carmakers ramping up electric vehicle production, the EV share of total car

sales is rising steadily worldwide. But even though Germany and Sweden have

roads that charge them, the global supply chain for lithium-ion batteries is

dirty and vulnerable. That’s why China’s CATL is developing (for Tesla)

cobalt-free batteries that don’t require mining in Africa and South America.

Hydrogen-powered public transport and cars are taking off in Japan, South

Korea, and China. Organic waste can be turned into synthetic gas to power

garbage trucks. And Toyota’s solar panel–covered car provides a day’s worth of

urban driving with no charging required.

It’s common today to

hear pronouncements about the “death of globalization.” Generations past have

presumed the same about their times. Yet much like Europe after World War I,

each period of retrenchment is followed by an even broader and deeper globalization

wave. So it shall be again. Oil trade may decrease, but the digital exchange is

exploding. Trade-in manufactured goods have ebbed, but capital flows and

cryptocurrencies are thriving. Populism and the pandemic have tightened some

borders, but climate change will drive ever more people across them. Remember

the most fundamental truth about humanity through the ages: We keep building

connectivity across the planet, and we keep using it.

Mobility is destiny.

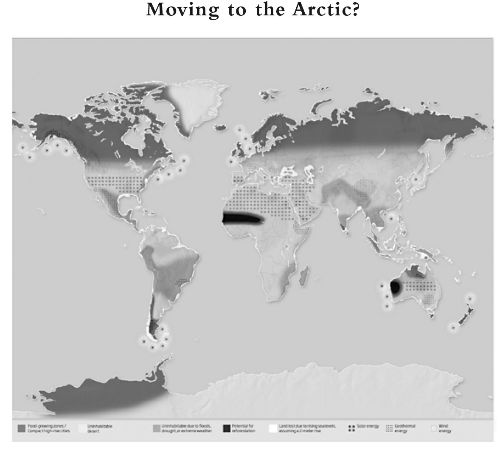

A map of the world population distribution in 2020 shows large concentrations

along the coasts of North America and the Pacific Rim and the dense urban

clusters of Europe, Africa, and South Asia. But as we animate that map toward

2050, the coastlines of North America and Asia will submerge, and their people

will retreat inland. South Americans and Africans will surge northward as their

farmland desertifies and their economies crumble.

South Asia, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, will be the origin of an even more

significant exodus as sea levels rise and rivers dry up. At the same time,

automation makes human labor redundant, and governments fail to provide

stability and welfare. As the decades unfold, dozens of new cities will pop up in

previously uninhabited regions, from the Canadian Arctic and Greenland to

Russian Siberia and the Central Asian steppe. Some towns will move with their

inhabitants.

The Covid lockdown

crushed the economy but (temporarily) cleared the skies. Millions of Indians

living in the foothills of the Himalayas had never seen its peaks until March

2020, when decades of oppressive smog were temporarily removed. Can we maintain

economic vibrancy while also eliminating noxious greenhouse gas emissions? The

Paris climate agreement has been held up as a road map for the world, but no

collective action has backed it up. American presidents can make promises that

their successors reject and Congress fails to legislate, and that would take

decades to implement. Canada is a signatory to the Paris Agreement but has just

approved the development of a massive new tar sands oil field. Europe is

reducing its emissions, but its efforts are more than outweighed by their

growth everywhere else. China is cleaning up at home but exporting dirty coal

abroad. India and Brazil decry climate colonialism while India remains reliant

on coal power, and Brazil logs the Amazon. Carbon taxes are gaining ground, but

these are, at best half measures. Markets, many critics argue, are what got us

into this mess in the first place.

Our many colonial-era

borders hinder cooperation on today’s existential challenges. For example,

India and Pakistan dispute the Sir Creek estuary that forms the Feni River’s

delta into the Arabian Sea. Here and elsewhere, countries can’t agree on a

river border. Instead, they should have been turned into wetland conservation

areas long ago. Some sub-Saharan African nations, such as Botswana and Zambia,

have managed to establish cross-border ecological preserves. The same should be

done in the precarious but ecologically precious Demilitarized Zone between

North and South Korea. Such thinking is needed across the world. Though the

notorious 1885 Congress of Berlin is where Africa got many of its straight-line

borders, Europeans also utilized the legal concept of do ut

des, meaning “giving to receive.” Today, they can also share sovereignty.

Sovereignty today

serves to demarcate zones of political control, but it also shields governments

from complying with transnational responsibilities. Yet climate change raises

new questions about countries’ obligations to conserve habitats, reduce greenhouse

gas emissions, and accept migrants. At the heart of these queries lies a stark

choice. What matters more: nationality or sustainability? Should states be

permitted to have leaders who ruin the Earth for all of us? Is the territory of

Canada or Russia too crucial to the world to be left to Canadians and Russians

alone to govern? Can we evolve from sovereignty to stewardship?

Repurposing vast

swaths of the planet for large-scale resettlement requires re-coding territory

away from strict sovereignty into administrative protectorates designated for

agriculture, forestry, marine life, or habitation. Countries could lease

critical habitats to international cooperatives for their sustainable

cultivation. When spaces are so crucial that no one government should control

them exclusively, we can design mechanisms that balance sustainability with

fair access. IUCN helps countries designate nature reserves, wilderness areas,

national parks, and sustainable resource development areas and finds partners

to assist them. To date, such technical support by IUCN and the World Wildlife

Fund has led to 15 percent of the Earth’s land area being designated as

protected areas. E. O. Wilson argued our target should be 50 percent. Linking

biospheres would allow many currently endangered species and natural habitats

to regenerate.

Twenty years ago, we

feared rampant overpopulation. Today’s most urgent task is to nurture those

alive and yet to be born to ensure the survival of humanity through this

century. Will people have to move, but will we let them? Is there any

justification for a system in which large and resource-rich countries close

their borders while those least responsible for climate change are sinking or

running out of water? To lock the world population into its present position

amounts to ecocide, yet it won’t make those who survive better off. Our

economies will still face acute labor shortages, and the wealth created from

the global exchange will halt. We should cultivate the planet’s habitable oases

and move people there.

Moral philosophers

have nonetheless put the nation ahead of humanity in their inquiries. For

example, seventeenth-century English philosopher John Locke argued for

naturalizing immigrants to enlarge the labor pool and expand production. He was

clear that migration should not deprive locals of their property rights. The

eighteenth-century Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant advocated a right to

hospitality for all people, but this was understood more as a temporary sojourn

rather than permanent residence. As with Locke, it was conditioned on the

visitor not causing harm to his hosts.2

Kant’s ideas

continued to animate twentieth-century debates about migrant rights. Living

through the postwar decades of significant migrations between Britain and its

former colonies, the late Oxford philosopher Michael Dummett echoed Kant in his

view that a moral state should provide fundamental rights to both citizens and

noncitizens alike. The right to migrate is such a right, as is the right of

stateless people to become citizens of some state. Jacques Derrida similarly

argued for strict national sovereignty to soften in favor of more ethical

hospitality toward foreigners. But even for famed philosophers such as John

Rawls, migration played a minor role in his thought experiments about

self-contained states. He supported people’s right to move, but not any

imposition on national sovereignty. Instead, a just global system would

eliminate the root causes of poverty, corruption, or other motivations for

migration.

Some European

conservatives argue that citizenship should only be conferred on those with a

“genuine” link to the country. This usage of “genuine” is specious, effectively

reducing citizenship back to the arbitrary happenstance of birth, hardly a

measure of genuine volition. The actual intent of criticizing

citizenship-for-sale programs, of course, is to avoid losing tax revenue. The

“Paradise Papers” (a trove of 13 million documents disclosing offshore

financial holdings of elites from around the world) revealed the extent to

which wealthy individuals, like stateless global companies, will go to hide

their assets in offshore jurisdictions.

The EU is pushing

back, demanding that companies registered in low-tax countries prove their

“economic substance” involves actual people living there. There must be

employees, not just shell companies. Governments count the number of days

people spend within their borders to tax them; soon, they will check your

passport dates and stamps and for whom you did the work. The likely result is

that people will vote with their wallets, moving themselves or their staff to

more tax-efficient places. Companies certainly are, whether Dyson is shifting

its headquarters from London to Singapore or SoftBank’s Vision Fund relocating

from London to Abu Dhabi.

Ireland is already a

tax haven for global tech companies and takes in tens of thousands of new

skilled residents each year, many living in “Googleville”

in central Dublin. After just one year and paying 1 million euros, residents

are eligible to apply for citizenship, enabling them to move at will to other

EU countries competing to attract migrant investors. (In mid-2020, Hong Kong

tycoon Ivan Ho proposed building a new city in Ireland called

Nextpolis to relocate fifty thousand Hong Kong

citizens.)

If countries don’t do

a better job moving their passports up the rankings of global access, their

citizens will just move and change citizenship. While Asian passports from

Japan, South Korea, and Singapore now sit atop the ranking of most powerful

passports, China ranks seventy-fourth, and India is far lower still. Each year,

about one hundred thousand, mostly Chinese and Indians, have come into New

Zealand either to stay or use it as a back door to enter Australia. After alarm

bells sounded, New Zealand backtracked on allowing any foreigners (save for

those from a handful of friendly countries or selected billionaires) to buy

property at all. Now those would-be Kiwis will likely become Canucks instead. A

Chinese proverb advises that a wise rabbit always has three holes to burrow in.

Chinese should know: They’re buying up properties and passports from Canada to

Portugal to Singapore.

So too are Americans.

Historically, Americans only expatriate after many years of frustration at US

tax filings. The ultra-rich 1 percent of American ex-pats can easily afford

either to renounce or to keep US citizenship. Still, it’s the 2 percent, 5 percent,

10 percent, and everyone else that struggles to save money while paying taxes

in two countries simultaneously.2 Punitive tax policy, political populism, and Covid

mismanagement drove a growing number of Americans to the exits throughout the

2010s. In the first half of 2020 alone, American expatriation reached nearly

six thousand worldwide, a 1,200 percent jump over the entire total of 2019, and

would have been even higher if not for the backlog of applicants at various

embassies. Departing elites have their pick of justifications: authoritarian

populist Republicans or woke socialist Democrats. Ironically, Italy and

Ireland, which provided so many grateful migrants to America in the nineteenth

century, are top destinations for Americans using their lineage to obtain

European passports for themselves, and their children too. Who knows where

America’s growing diaspora will go next?

Even those with an American

passport or green card have no longer considered America a haven. An estimated

6 million Americans also hold other passports, they’re “American” on paper, but

America is more a backup plan than a pledge of allegiance. Now both Americans

and these secondary US passport holders are having second thoughts. Even more,

foreigners give up their green cards each year than Americans give up

passports. America’s lost its dominant grip on the best and brightest students,

is losing appeal as a nationality, and is competing in a war for global wealth

and talent, including Americans.

The term “user

experience” applies as much to cities as it does to companies for youth. They

demand that local governance leapfrog from decrepit infrastructure and shoddy

services to sensors managing traffic and digital referenda gathering their

views in real-time. Small and wealthy countries tend to offer the best

combination of security and lifestyle that youth seek, but cities will compete

to be “smarter” than their peers within large countries such as the US.3

“Smart city” now

denotes everything from telemedicine to pervasive surveillance. The

technological dimension of smart city life is a mix of alluring and

discomforting. Apartments are becoming configurable spaces where the furniture

folds itself up to fit the area depending on whether you need a couch, bed,

kitchen, or office.

It’s common today to

hear pronouncements about the “death of globalization.” Generations past have

presumed the same about their times. Yet much like Europe after World War I,

each period of retrenchment is followed by an even broader and deeper globalization

wave. So it shall be again. Oil trade may decrease, but the digital exchange is

exploding. Trade-in manufactured goods have ebbed, but capital flows and

cryptocurrencies are thriving. Populism and the pandemic have tightened some

borders, but climate change will drive ever more people across them. Remember

the most fundamental truth about humanity through the ages: We keep building

connectivity across the planet, and we keep using it.

Mobility is destiny.

A map of the world population distribution in 2020 shows large concentrations

along the coasts of North America and the Pacific Rim and the dense urban

clusters of Europe, Africa, and South Asia. But as we animate that map toward

2050, the coastlines of North America and Asia will submerge, and their people

will retreat inland. South Americans and Africans will surge northward as their

farmland desertifies and their economies crumble.

South Asia, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, will be the origin of an even more

significant exodus as sea levels rise and rivers dry up. At the same time,

automation makes human labor redundant, and governments fail to provide

stability and welfare. As the decades unfold, dozens of new cities will pop up in

previously uninhabited regions, from the Canadian Arctic and Greenland to

Russian Siberia and the Central Asian steppe. Some towns will move with their

inhabitants.

Our many arbitrary

colonial-era borders hinder cooperation on today’s existential demographic and

environmental challenges. For example, India and Pakistan dispute the Sir Creek

estuary that forms the Feni River’s delta into the Arabian Sea. Here and elsewhere,

countries can’t agree whether a river border should be defined at the midpoint

or the banks. Yet as University of Maryland professor Saleem Ali argues, such

fragile ecosystems should have been turned into wetland conservation areas long

ago rather than militarized. Some sub-Saharan African nations, such as Botswana

and Zambia and Mozambique, and South Africa, have established cross-border

ecological preserves. The same should be done in the precarious but

ecologically precious Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea. Such

thinking is needed across the world. Though the notorious 1885 Congress of

Berlin is where Africa got many of its straight-line borders, Europeans also

utilized the legal concept of do ut des, meaning

“giving to receive,” or simply tit-for-tat. Today countries can do better than

that: They can also share sovereignty.

Sovereignty today

serves to demarcate zones of political control, but it also shields governments

from complying with transnational responsibilities. Yet climate change raises

new questions about countries’ obligations to conserve habitats, reduce greenhouse

gas emissions, and accept migrants. At the heart of these queries lies a stark

choice. What matters more: nationality or sustainability? Should states be

permitted to have leaders who ruin the Earth for all of us? Is the territory of

Canada or Russia too crucial to the world to be left to Canadians and Russians

alone to govern? Can we evolve from sovereignty to stewardship?

Repurposing entire

swaths of the planet for large-scale resettlement requires re-coding territory

away from strict sovereignty into administrative protectorates designated for

agriculture, forestry, marine life, or habitation. In this spirit, countries could

lease critical habitats to international cooperatives for their sustainable

cultivation. When spaces are so crucial that no one government should control

them exclusively, we can design mechanisms that balance sustainability with

fair access. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) helps

countries designate nature reserves, wilderness areas, national parks, and

sustainable resource development areas and finds the right partners to assist

them to protect, regenerate, or attract tourists to these ecozones. To date,

such technical support by IUCN and the World Wildlife Fund has led to 15

percent of the Earth’s land area being designated as protected areas. E. O.

Wilson argued our target should be 50 percent, half the Earth. Linking biospheres

would allow many currently endangered species and natural habitats to

regenerate, from North American forests to the Amazon river basin to African

grasslands.

If temperatures rise

by four degrees Celsius, Canada, northern Europe, and Russia would be the only

regions of the planet suitable for year-round human habitation. Due to droughts

and other environmental hazards, today’s most populous countries, such as China,

India, and the US, would be unsuitable. However, the US and other parts of the

world could still be producers of solar, wind, and other renewable power

sources.

And yet, we will try.

America’s only partially Arctic state, Alaska, has been flagged in the EPA’s

Climate Resilience Screening Index (CSRI) as having the highest number of counties

prepared for climate hazards. With its low population density, it also had the

lowest Covid infection rate of any American state. But currently, Alaska is

losing people annually to better jobs in the lower forty-eight states. It will

undoubtedly attract rugged Americans seeking a low tax escape to start a new

life and enjoy less scorching weather. But even in Alaska, dozens of coastal

towns are engulfed by rising Pacific tides, while heat waves have been killing

salmon in rivers before they can spawn. Farther inland, oil drilling and timber

logging threaten the state’s nature preserves. A fresh start may well mean

building new towns altogether. There and across Canada, one will find an

archipelago of new Arctic melting pots.

In Europe, the gold

rush for Arctic real estate has already begun, driven not least by massive

gusts of hot Saharan desert blasting north from Africa. Before the long heat

spell of 2019 arrived, a Spanish meteorologist announced, “Hell is coming.” A

longer dry season in Germany’s Brandenburg region has caused wildfires and

ashen haze in Berlin, with similarly black-red skies during heat waves in

Moscow as well. Scandinavian property developers keenly offer summer dachas to

Europeans from farther south. The first company that announces it’s building an

Arctic outpost to relocate its staff during the summer will need AI to scan

through all the CVs flooding its inbox. After all, with twenty-plus hours of

daylight in the summer, there will be plenty of time for both works and

play.

Arctic territories

will take on a new purpose: to build something for humanity where there was

only nature before. Like the Amish or Mennonite communities who pioneered

westward in nineteenth-century America, small communes will strive to live

off-grid, harnessing local water supplies and agriculture to reduce dependence

on the wild world beyond their horizon. The Arctic will also be tempting for

scientists, engineers, environmentalists, and financiers to establish research

settlements. They’re already coding their digital community by simulating

architecture in VR and transacting in cashless blockchain contracts. Next,

they’ll raise funds from investors and negotiate with governments to grant them

land to colonize in exchange for investment and access to the benefits from

these new businesses. It will be, in the words of Balaji Srinivasan,

“Cloud-first, land last.”

A more populous

Arctic region may come to resemble the resource-rich continent of South

America, where indigenous people, Iberian colonists, African slaves, Europeans

and Asians escaping hunger, and Arabs fleeing civil war have all layered over

the centuries into a unique milieu. Over time, one should expect to see in the

Arctic not only Europeans, Russians, and North Americans, but Syrian and Indian

farmers, Chinese and Turkish industrial engineers, and dozens of other

nationalities planting trees, building settlements, and harvesting resources.

What better geography to promote a new orientation for human identity than the

barren far north, which for centuries was stateless terrain?

When the ice melts

At the same time, the

land grab for resource extraction, agro-industry, and real estate development

will accelerate. The

Inuit and Sami people already subsist precariously off the land and sea as the

ice melts. A new commercial influx may further force them onto

reservations, as with Native Americans in the US and aboriginals in Australia.

This would be a reversal for Canada, given the First Nations' significant

autonomy in recent decades. Mining companies, billionaire environmentalists,

and indigenous peoples may battle in courts and on the ground over

sovereignty.

Arctic geopolitics

may also further heat the already warming northern cone. New shipping routes

allow North Americans, Europeans, and Asians to evade traditional bottlenecks

such as the Suez Canal or Strait of Malacca. At the same time, Russia is

deploying armored icebreakers and nuclear submarines to assert its territorial

claims as mineral deposits are discovered. Once Arctic states disputed claims

on the ice sheet, they’ll now do so on the ocean floor. Given the lucrative

resources and trade routes, the Arctic represents, perhaps piracy will migrate

north too.

China has taken a

growing interest in the Arctic, declaring it a “polar Silk Road.” Chinese

investors have sought to buy strategic tracts of land in Iceland and Norway,

but Nordic democracies have rebuffed offers that don’t involve full local

control and democratic scrutiny.

Shanghai:

A scenario

amalgamating these trends points to the rise of a network of northern

hemispheric trading hubs across which hundreds of millions of people may

eventually circulate. This revival of the early medieval Hanseatic League, with

members spanning beyond Hamburg and Tallinn to include St. Petersburg,

Reykjavik, Kirkenes, Aberdeen, Nuuk, Churchill, and other like-minded

entrepôts, signals a future in which once again city-states and their chambers

of commerce drive vital global relations among pragmatic trading powers.

Can we pre-design our

movements into the Arctic latitudes in such a way that we tread lightly,

gradually preparing the terrain to absorb populations without destroying the

resources on which we depend? Or will we bring rapacious extraction,

pestilence, and geopolitical troubles as we have elsewhere in the past? If we

don’t get the Arctic right, there won’t be any other options left.

1. According to the Healthcare

Access and Quality (HAQ) Index, the three best healthcare systems are in Iceland,

Norway, and the Netherlands. Universal healthcare is offered in eighteen

countries: Australia, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland,

Ireland, Israel, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, the Slovak

Republic, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. In addition,

Austria, Belgium, Japan, and Spain have near-universal health coverage.

2. Kant was, not

incidentally, one of the first philosophers to treat geography as a discipline,

outlining its subcategories, such as physical, economic, and moral. He wrote of

a “philosophical topography” to explain how spaces and places shape human experience

and knowledge. Malpas and Thiel, “Kant’s Geography of Reason,” Reading Kant’s

Geography (2011), in Robert B. Louden, “The Last Frontier: The Importance of

Kant’s Geography,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32, no.3

(January 2014): 450–465.

3. A joint report by

IMD of Switzerland and the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD)

ranks cities based

on their technology deployment to improve citizen experience.

For updates click homepage here