By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Göbekli Tepe revisited part two

As we have seen in

part one, whether we go with Hobbes (or Rousseau), we are left with

the idea that the most we can do to change our current predicament are a bit of

modest political tinkering. Hierarchy and inequality are the inevitable prices

to pay for having genuinely come of age yet except what the available

evidence shows are that the trajectory of human history has been a good deal

more diverse and exciting and less boring than we tend to assume because, in an

important sense, it has not been a trajectory.

James C. Scott – a renowned political scientist

who has devoted much of his career to understanding the role of states (and

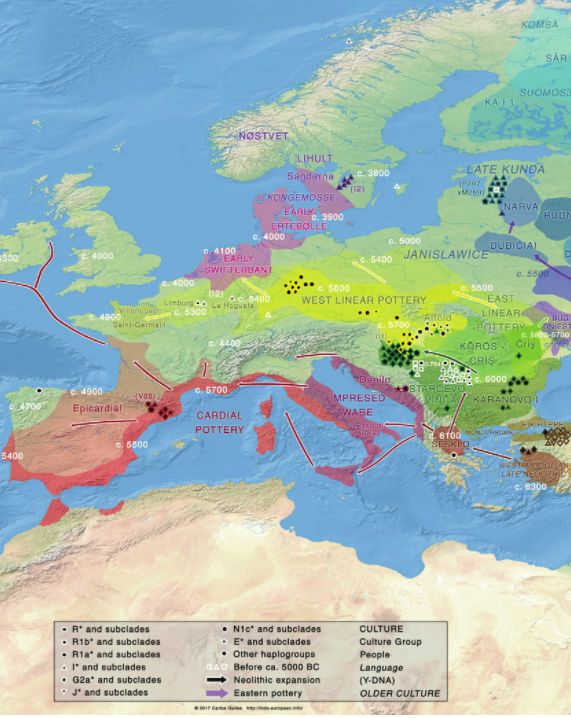

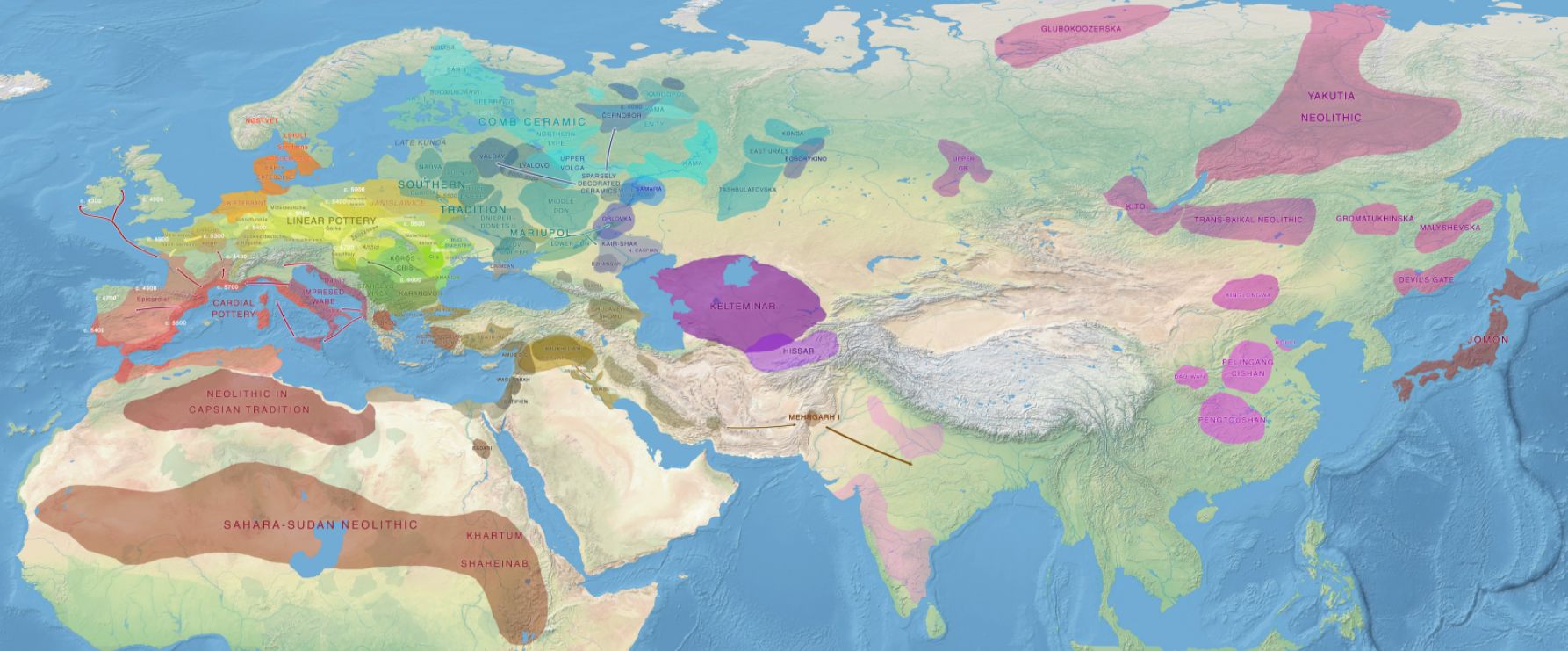

those who succeed in evading them) in human history. The Neolithic, he

suggests, began with flood-retreat agriculture, which was easy work and

encouraged redistribution; the largest populations were, indeed, concentrated

in deltaic environments, but the first states in the Middle East developed

upriver, in areas with a solid focus on cereal agriculture – wheat, barley,

millet – and relatively limited access to a range of other staples. The key to

the importance of grain, Scott notes, is that it was durable, portable, easily

divisible, and quantifiable by bulk. Therefore, it was an ideal medium to serve

as a basis for taxation. Growing above ground – like certain tubers or legumes

– grain crops were also evident and amenable to appropriation. Cereal

agriculture did not cause the rise of extractive states, but it was certainly

predisposed to their fiscal requirements.1

That indigenous doctrines of individual liberty,

mutual aid, and political equality, which made such an impression on French

Enlightenment thinkers, were neither (as many of them supposed) the way all

humans can be expected to behave in the State of Nature. Instead, certain

freedoms – to move, disobey, and rearrange social ties – tend to be taken for

granted by anyone who has not been trained explicitly into obedience (as anyone

reading this book, for instance, is likely to have been). Still, the societies that

European settlers encountered only really make sense as the product of a

specific political history: a history in which questions of hereditary power,

revealed religion, personal freedom, and the independence of women were still

very much matters of self-conscious debate,

Most people feel a spontaneous affinity with the

story’s tragic version, not just because of its scriptural roots. The more

rosy, optimistic narrative fails to explain why Western civilization inevitably

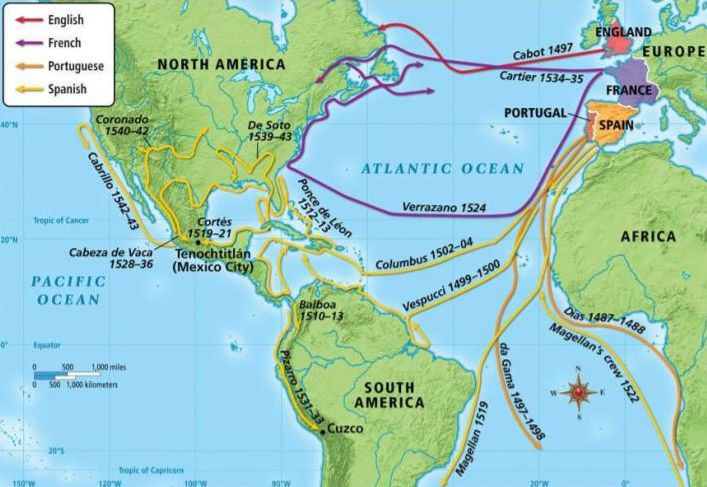

makes everyone happier, wealthier, and more secure. This is why European powers

should have been obliged to spend 500 or so years (as we have seen in the economics of colonialism) aiming guns at

people’s heads to force them to adopt it. During the nineteenth-century heyday

of European imperialism, everyone seemed more keenly aware of this.

European statesmen and intellectuals of that time were

just as likely to be obsessed with the dangers of decadence and disintegration.

Many were overt racists who held that most humans are not capable of progress

and therefore looked forward to their physical extermination. Even those who

did not share such views tended to feel that Enlightenment schemes for

improving the human condition had been catastrophically naive. As a result, the

social sciences were conceived and organized around two core questions: (1)

what had gone wrong with the project of Enlightenment, with the unity of

scientific and moral progress, and with schemes for the improvement of human

society? And: (2) why is it that well-meaning attempts to fix society’s

problems so often end up making things even worse?

But throughout the argument, all parties have come to

agree on one key point: that there was indeed something called ‘the

Enlightenment, that it marked a fundamental break in human history, and that

the American and French Revolutions were in some sense the result of this

rupture. The Enlightenment is seen as introducing a possibility that had not

existed before: that of self-conscious projects for reshaping society in accord

with some rational ideal.

For much of the twentieth century, anthropologists

described the societies they studied in ahistorical terms as living in a kind

of eternal present. Some of this was an effect of the colonial situation under which

much ethnographic research was carried out. The British Empire, for instance, maintained

a system of indirect rule in various parts of Africa, India, and the Middle

East where local institutions like royal courts, earth shrines, associations of

clan elders, men’s houses, and the like were maintained in place, indeed fixed

by legislation. Significant political change – forming a political party, say,

or leading a prophetic movement – was in turn entirely illegal, and anyone who

tried to do such things was likely to be put in prison. This made it easier to

describe the people anthropologists studied as having a way of life that was

timeless and unchanging. Since historical events are by definition

unpredictable, it seemed more scientific to study those phenomena one could

predict: the things that kept happening, over and over, in roughly the same

way.

Social science has mainly been a study of how human

beings are not free: the way that our actions and understandings might be

determined by forces outside our control. Any account which appears to show

human beings collectively shaping their destiny, or even expressing freedom for

its own sake, will likely be written off as illusory, awaiting ‘real’

scientific explanation; or if none is forthcoming, as outside the scope of

social theory entirely. This is one reason why most ‘extensive histories’ place

such a strong focus on technology. Dividing up the human past according to the

primary material from which tools and weapons were made (Stone Age, Bronze Age,

Iron Age) or else describing it as a series of revolutionary breakthroughs,

they then assume that the technologies themselves largely determine the shape

that human societies will take for centuries to come or at least until the next

abrupt and unexpected breakthrough comes along to change everything again.

Technologies play an essential role in shaping

society. They open up new social possibilities never before. It’s easy to

overstate the importance of new technologies in setting the overall direction

of social change. For example, it’s well known that Teotihuacanos

or Tlaxcalteca employed

stone tools to build and maintain their cities.

This, while the inhabitants of Mohenjo-Daro or

Knossos, used

metal, which seems to have made surprisingly little difference to those

cities’ internal organization or even size. Nor does our evidence support the

notion that significant innovations always occur in sudden, revolutionary

bursts, transforming everything in their wake.

While human beings have always been capable of physically

attacking one another (and it’s difficult to find examples of societies where

no one ever attacks anyone else, under any circumstances), there’s no actual

reason to assume that war has always existed. Technically, war refers to

organized violence and a kind of contest between two demarcated sides. As

Raymond Kelly has adroitly pointed out, it’s based on a logical principle

that’s by no means natural or self-evident, which states that significant

violence involves two teams. Any member of one team treats all members of the

other as equal targets. Kelly calls this the principle of ‘social

substitutability.’

Another question is whether there is a relationship

between external warfare and the internal loss of freedoms that opened the way,

first to systems of ranking and then to large-scale systems of domination. How

direct was this correlation? One thing we’ve learned is that it’s a mistake to

assume these ancient polities were simply archaic versions of our modern

states. As we know it today, the state results from a distinct combination of

elements – sovereignty, bureaucracy, and a competitive political field.

Where two axes of power were developed and formalized

into a single system of domination, we can begin to talk of ‘second-order

regimes.’ The architects of Egypt’s Old Kingdom, for example, armed the

principle of sovereignty with a bureaucracy and managed to extend it across a

large territory. By contrast, the rulers of ancient Mesopotamian city-states

made no direct claims to sovereignty, which for them resided properly in

heaven. When they engaged in wars over land or irrigation systems, it was only

as secondary agents of the gods. Instead, they combined charismatic competition

with a highly developed administrative order. The Classic Maya was different

again, confining administrative activities mainly to monitoring cosmic affairs

while basing their earthly power on a potent fusion of sovereignty and

inter-dynastic politics. Insofar as these and other polities commonly regarded

as ‘early states’ (Shang China, for instance) share any common features, they

seem to lie in altogether different areas – which brings us back to the

question of warfare and the loss of freedoms within society. All of them

deployed spectacular violence at the pinnacle of the system (whether that

violence was conceived as a direct extension of royal sovereignty or carried

out at the behest of divinities), and all to some degree modeled their centers

of power – the court or palace – on the organization of patriarchal households.

Is this merely a coincidence? On reflection, the same combination of features

can be found in most later kingdoms or empires, such as the Han, Aztec or

Roman.

Shang China might well

be considered the paradigm for what the anthropologist Stanley Tambiah (1973)

has described as ‘galactic

polities’, also the most common form in later Southeast Asian history,

where sovereignty concentrated at the center and then attenuated outwards,

focusing in some places, fading in others to the point where, at the edges,

certain rulers or nobles might actually claim to be part of empires – even

distant descendants of the founders of empires – whose current ruler had never

heard of them. We can contrast this sort of outward proliferation of

sovereignty with another kind of macro-political pattern, emerging first in the

Middle East and then gradually across

much of Eurasia, where diametrically opposed notions of what actually

constitutes ‘government’ would face off against each other in dynamic tension,

creating the great frontier zones that separated bureaucratic regimes

(whether in China, India or Rome) from the heroic politics of nomadic peoples

which threatened constantly to overwhelm them.

James Scott, a renowned political scientist who has

devoted much of his career to understanding the role of states in human

history, has a compelling description of how this agricultural trap works. The

Neolithic, he suggests, began with flood-retreat agriculture, which was easy

work and encouraged redistribution; the most significant populations were

concentrated in deltaic environments. However, the first states in the Middle

East developed upriver, in areas with an especially strong focus on cereal agriculture.

The key to the importance of grain, Scott notes, is its durable, portable,

easily divisible, and quantifiable by bulk. Therefore, it was an ideal medium

to serve as a basis for taxation. Growing above ground – like certain tubers or

legumes – grain crops were also obvious and amenable to appropriation. Cereal

agriculture did not cause the rise of extractive states, but it was certainly

predisposed to their fiscal requirements.1

That indigenous doctrines of individual liberty,

mutual aid, and political equality, which made such an impression on French

Enlightenment thinkers, were neither the way all humans can be expected to

behave in the State of Nature. Nor were they (as many now assume) simply the

way culture happened to crumble in that particular part of the world. This is

not to say there is no truth whatsoever in either of these positions. There are

certain freedoms – to move, to disobey, to rearrange social ties – that tend to

be taken for granted by anyone who has not been trained explicitly into

obedience, is likely to have been. Still, the societies that European settlers

encountered only really make sense as the product of a specific political

history: a history in which questions of hereditary power, revealed religion,

personal freedom, and the independence of women were still very much matters of

self-conscious debate.

Most people feel a spontaneous affinity with the

story’s tragic version, not just because of its scriptural roots. The more

rosy, optimistic narrative – whereby the progress of Western civilization

inevitably makes everyone happier, wealthier, and more secure – has at least

one obvious disadvantage. It fails to explain why that civilization did not

simply spread of its own accord; that is, why European powers should have been

obliged to spend the last 500 or so years aiming guns at people’s heads to force

them to adopt it. (Also, if being in a ‘savage’ state was so inherently

miserable, why so many of those same Westerners, given an informed choice, were

so eager to defect to it at the earliest opportunity.) During the

nineteenth-century heyday of European imperialism, everyone seemed more keenly

aware of this.

An answer is suggested by the West Indian sociologist

Orlando Patterson, who points out that Roman Law conceptions of property (and

hence of freedom) essentially trace back to slave law.2 The reason it is

possible to imagine the property as a relationship of domination between a

person and a thing is that, in Roman Law, the power of the master rendered the

slave a thing (res, meaning an object), not a person with social rights or

legal obligations to anyone else. Property law, in turn, was mainly about the complicated

situations that might arise as a result. It is important to recall, for a

moment, who these Roman jurists were that laid down the basis for our current

legal order – our theories of justice, the language of contract and torts, the

distinction of public and private, and so forth. While they spent their public

lives making sober judgments as magistrates, they lived their personal lives in

households where they not only had near-total authority over their wives,

children, and other dependants but also had all their

needs taken care of by dozens, perhaps hundreds of slaves. Slaves trimmed their

hair, carried their towels, fed their pets, repaired their sandals, played

music at their dinner parties, and instructed their children in history and maths. At the same time, in terms of legal theory, these

slaves were classified as captive foreigners who, conquered in battle, had

forfeited rights of any kind. As a result, the Roman jurist was free to rape,

torture, mutilate or kill any of them at any time and in any way he had a mind

to, without the matter being considered anything other than a private affair.

(Only under the reign of Tiberius were any restrictions imposed on what a

master could do to a slave, and what this meant was simply that permission from

a local magistrate had to be obtained before a slave could be ripped apart by

wild animals; other forms of execution could still be imposed at the owner’s

whim.) On the one hand, freedom and liberty were private affairs; on the other,

private life was marked by the absolute power of the patriarch over conquered

people who were considered his private property.3 The fact that most Roman

slaves were not prisoners of war, in the literal sense, doesn’t make much

difference here.

We can also look at monarchy, warrior aristocracies,

or other forms of stratification taking hold in urban contexts. When this

happened, the consequences were dramatic. Still, the mere existence of large

human settlements in no way caused these phenomena and certainly didn’t make

them inevitable. We must look elsewhere. Hereditary aristocracies were just as

likely to exist among demographically small or modest-sized groups, such as the

societies of the Anatolian highlands.

Social theorists tend to write about the past as if

everything that happened could have been predicted. This is somewhat dishonest

since we’re all aware that when we try to predict the future, we almost

invariably get it wrong – and this is just as true of social theorists as

anybody else. Nonetheless, it’s hard to resist the temptation to write and

think as if the current state of the world, in the early twenty-first century,

is the inevitable outcome of the last 10,000 years of history, while in reality,

of course, we have little or no idea what the world will be like even in 2075,

let alone 2150.

On the one hand, fundamental breakthroughs in the

physical sciences, or even artistic expression, no longer seem to occur with

anything like the regularity people came to expect in the late nineteenth and

early twentieth centuries. Yet, at the same time, our scientific means of

understanding the past, not just our species’ past but that of our planet, has

been advancing with dizzying speed. Scientists in 2020 are not (as readers of

mid-twentieth-century science fiction might have hoped) encountering alien civilizations

in distant star systems, but they are encountering radically different forms of

society under their own feet, some forgotten and newly rediscovered, others

more familiar, but now understood in entirely new ways.

No doubt, for a while, at least, very little will

change. Whole fields of knowledge – not to mention university chairs and

departments, scientific journals, prestigious research grants, libraries,

databases, school curricula, and the like – have been designed to fit the old

structures and the old questions.

Max Planck once remarked that new scientific truths

don’t replace old ones by convincing established scientists that they were

wrong; they do so because proponents of the older theory eventually die, and

generations find the new truths and theories familiar evident even.

We can see more clearly now what is going on when, for

example, a study that is rigorous in every other respect begins from the

unexamined assumption that there was some ‘original’ form of human society;

that its nature was fundamentally good or evil; that a time before inequality

and political awareness existed; that something happened to change all this;

that ‘civilization’ and ‘complexity’ always come at the price of human

freedoms; that participatory democracy is natural in small groups but cannot

possibly scale up to anything like a city or a nation-state. We know, now, that

we are in the presence of myths.

1. James C. Scott, Against the Grain:

A Deep History of the Earliest States, 2017,129-30.

2. Orlando Patterson, Slavery and

Social Death: A Comparative Study. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press, 1982, 10.

3. David Graeber, Debt: The First 5,000

Year, 2011, 198–201

For updates click homepage here