By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Göbekli Tepe revisited

part three

Of the world’s significant Neolithic expansions

took place in island Oceania. Its origins lay at the other end of Asia, in the

rice- and millet-growing cultures of Taiwan and the Philippines (the deeper

roots are in China). Around 1600 BC, a striking dispersal of farming groups

occurred, starting here and ending over 5,000 miles to the east in Polynesia.

Local seed crops were cultivated by 3000

BC, but there was no ‘serious farming’ until around AD 1000. China follows a

similar pattern. Millet farming began on a small scale around 8000 BC as a

seasonal complement to foraging and dog-assisted hunting. It remained so for

3,000 years until the introduction of cultivated millets into the basin of the

Yellow River. Similarly, on the lower and middle reaches of the Yangtze, fully

domesticated rice strains only appeared fifteen centuries after the first

cultivation of wild rice. It might have taken longer were it not for a snap of

global cooling around 5000 BC, which depleted wild rice stands and nut

harvests.1 In both parts of China, pigs still came second to wild boar and deer

in terms of dietary significance long after their domestication.

But the scale of pre-Columbian capitals

like Teotihuacan or Tenochtitlan dwarfs that of the earliest cities in China

and Mesopotamia. It makes the ‘city-states’ of Bronze Age Greece (like Tiryns

and Mycenae) seem little more than fortified hamlets.

We now know that in China’s Shandong

province, on the lower reaches of the Yellow River, settlements of 300 hectares

or more were present by no later than 2500 BC, which is over 1,000 years before

the earliest royal dynasties developed on the Central Chinese plains. On the

other side of the Pacific, around the same time, ceremonial centers of great

magnitude developed in the valley of Peru’s Rio Supe, notably at Caral.2 The

extent of human habitation around these great centers is still to be

determined. These new findings show that archaeologists still have much to find

out about the distribution of the world’s first cities. They also indicate how

much older those cities may be than the systems of authoritarian government and

literate administration that were once assumed necessary for their foundation.

When historians, philosophers, or

political scientists argue about the origin of the state in ancient Peru or

China, what they are doing is projecting that a rather unusual constellation of

elements backward: typically, by trying to find a moment when something like

sovereign power came together with something like an administrative system (the

competitive political field is usually considered somewhat optional). What

interests them is precisely how and why these elements came together in the

first place. For instance, a classic story of human political evolution told by

earlier scholars was that states arose from the need to manage complex

irrigation systems, or perhaps just large concentrations of people and

information. This gave rise to top-down power, which eventually came to be

tempered by democratic institutions.

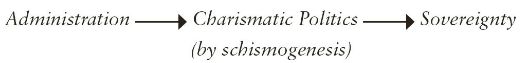

That would imply a sequence of

development somewhat like this:

![]()

Evidence from ancient Eurasia now points

to a different pattern, where urban administrative systems inspire a cultural

counter-reaction (a further example of schismogenesis), in the form of squabbling highland

princedoms (‘barbarians,’ from the perspective of the city dwellers),3 which

eventually leads to some of those princes establishing themselves in cities and

systematizing their power:

This may well have happened in some

cases, but it seems unlikely to be the only way in which such developments

might culminate in something resembling a state. In other places and times, the

process may begin with the elevation to pre-eminent roles of charismatic

individuals who inspire followers to make a radical break with the past.

Eventually, such figureheads assume a kind of absolute, cosmic authority, which

is finally translated into a system of bureaucratic roles and offices.4 The

path than might look more like this:

![]()

What we are challenging here is not any

particular formulation but the underlying teleology. All these accounts seem to

assume that there is only one possible endpoint to this process: that these

various types of domination were somehow bound to come together, sooner or

later, in something like the particular form taken by modern nation-states in

at the end of the eighteenth century. What if this wasn’t true?

Already during the early 1940’s Alfred

Kroeber, a pre-eminent anthropologist of his day spent decades on a research

project aimed at determining if identifiable laws lie behind the rhythms and

patterns of cultural growth and decay: whether systematic relations could be

established between artistic fashions, economic booms and busts, periods of

intellectual creativity and conservatism, and the expansion and collapse of

empires. It was an intriguing question, but his ultimate conclusion was: no,

there were no such laws after many years. In his Configurations of Cultural

Growth (1944), Kroeber examined the relation of the arts, philosophy, science,

and population across human history and found no evidence for any consistent

pattern; nor has any such pattern been successfully discerned in those few more

recent studies which continue to plow the same furrow.5

Despite this, when we write about the

past today, we almost invariably organize our thinking as if such patterns did

exist. Civilizations are typically represented either as flower-like – growing,

blooming, and then shriveling up – or like some grand building, painstakingly

constructed but prone to sudden ‘collapse.’

Some periods are dismissed as prefaces,

others as postfaces, but Egypt is one of those. Museumgoers will likely know

the division of ancient Egyptian history into Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms.

Each is separated by an ‘intermediate’ period, often described as epochs of

‘chaos and cultural degeneration.’ These were simply periods when there was no

single ruler. Authority devolved to local factions or, as we will shortly see,

changed its nature altogether. Taken together, these intermediate periods span

about a third of Egypt’s ancient history, down to the accession of a series of

foreign or vassal kings, and they saw some very significant political

developments of their own.

To take just one example, at Thebes

between 754 and 525 BC – spanning the Third Intermediate and Late periods – a

series of five unmarried, childless princesses (of Libyan and Nubian descent)

were elevated to the position of ‘god’s wife of Amun,’ a title and role which

acquired not just supreme religious, but also significant economic and

political weight at this time. In official representations, these women are

given ‘throne names’ framed by cartouches, just like kings, and appear leading

royal festivals and making offerings to the gods.6 They also owned some of the

wealthiest estates in Egypt, including extensive lands and a large staff of

priests and scribes. To have a situation in which women not only command power

on such a scale but in which this power is linked to an office reserved

explicitly for single women. Yet this political innovation is little discussed,

partly because it is already framed within an ‘intermediate’ or ‘late’ period

that signals its transitory (or even decadent) nature.7 One might assume the

division into Old, Middle and New Kingdoms is very ancient, perhaps going back

thousands of years to Greek sources like the third-century BC Aegyptiaca, composed by Egyptian chronicler Manetho, or

even to the hieroglyphic records themselves. Not so. The tripartite division

only began to be proposed by modern Egyptologists in the late nineteenth

century. The terms they introduced (initially ‘Reich’ or ‘empire,’ later

‘kingdom’) were explicitly modeled on European nation-states. German, mainly Prussian,

scholars played a leading role here. Their tendency to perceive ancient Egypt’s

past as a series of cyclical alternations between unity and disintegration

echoes the political concerns of Bismarck’s Germany, where an authoritarian

government was trying to assemble a unified nation-state from an endless

variety of tiny statelets. After the First World War, as Europe’s regime of old

monarchies was coming apart, prominent Egyptologists such as Adolf Erman

granted the ‘Intermediate’ periods their place in history, drawing comparisons

between the end of the Old Kingdom and the Bolshevik Revolution of their own

time.8

With hindsight, it’s easy to see just

how much these chronological schemes reflect their authors’ political concerns.

Or even, perhaps, a tendency – when casting their minds back in time – to

imagine themselves either as part of the ruling elite or as having roles

somewhat analogous to ones they had in their societies: the Egyptian or Maya

equivalents of museum curators, professors, and middle-range functionaries. But

why, then, have these schemes become effectively canonical?

Consider the Middle Kingdom (2055–1650

BC), represented in standard histories as a time when Egypt moved from the

supposed chaos of the First Intermediate period into a renewed phase of strong

and stable government, bringing artistic and literary renaissance.9 Even if we

set aside the question of just how chaotic the ‘intermediate period’ really was

(we’ll get to that soon), the Middle Kingdom could equally well be represented

as a period of violent disputes over royal succession, crippling taxation, state-sponsored

suppression of ethnic minorities, and the growth of forced labor to support

royal mining expeditions and construction projects – not to mention the brutal

plundering of Egypt’s southern neighbors for slaves and gold. However many

future Egyptologists would come to appreciate them, the elegance of Middle

Kingdom literature like The Story of Sinuhe and the proliferation of Osiris

cults likely offered little solace to the thousands of military conscripts,

forced laborers, and persecuted minorities of the time, many of whose

grandparents were living relatively peaceful lives in the preceding ‘dark

ages.’

What is true of time, incidentally, is

also true of space. For the last 5,000 years of human history – i.e., our

conventional vision of world history is a chequerboard of cities, empires, and

kingdoms; but, for most of this period, these were exceptional islands of

political hierarchy, surrounded by much larger territories whose inhabitants,

if visible at all to historians’ eyes, are variously described as ‘tribal

confederacies,’ ‘amphictyonies’ or (if you’re an anthropologist) ‘segmentary

societies’ – that is, people who systematically avoided fixed, overarching

systems of authority.

Those times and places have usually

taken to mark ‘the birth of the state.’ We may be seeing how very different

kinds of power crystallize, each with its peculiar mix of violence, knowledge,

and charisma: our three elementary forms of domination.

In China, archaeology has opened a

yawning chasm between the birth of cities and the appearance of the earliest

named royal dynasty, the Shang.

Early on Swedish geologist Johan Gunnar

Andersson discovered similarities between the Yangshao

Culture's unearthed painted pottery and the painted pottery of Central Asia. as

well as those of the Tripolye Culture in Tripoli in

the northwest of the Black Sea.

Seen here are three Chalcolithic ceramic

vessels (from left to right): a bowl on stand, a vessel on the stand, and an

amphora, ca. 4300–4000 BC; from Scânteia, Romania:

The Yangshao

Culture, which can be traced back to 4,900BC to 2,900BC, is a Neolithic culture

that existed extensively along the Yellow River in China. The culture

flourished mainly in what is today Northwest China's Shaanxi Province, North

China's Shanxi Province, and Central China's Henan Province.

Unearthed painted pottery from the Yangshao

Culture

As we have seen in part one the problem is not merely

one of time but also of space. Astonishingly, some of the most striking

‘Neolithic’ leaps towards urban life are now known to have taken place in the

far north, on the frontier with Mongolia. From the perspective of later Chinese

empires (and the historians who described them), these regions were already

halfway to ‘nomad barbarian and would eventually go beyond the Great Wall.

Nobody expected archaeologists to find there, of all places, a 4,000-year-old

city, extending over 400 hectares, with a great stone wall enclosing palaces

and a step-pyramid, lording it over a subservient rural hinterland nearly 1,000

years pre-Shang.

At the site of Taosi –

contemporary with Shimao, but located far to the south in the Jinnan basin – we find a rather different story.

Between 2300 and 1800 BC, Taosi went

through three phases of expansion.

According to Chinese archaeologists, the

Yangshao Culture was the first integration of Chinese

prehistoric culture. And agreed that in the future, we might not limit Chinese

history to the Zhou, Qin, and Han dynasties (1046 BC-AD 220), but will trace it back

to the Yangshao era.

That indigenous doctrines of individual

liberty, mutual aid, and political equality, which made such an impression on

French Enlightenment thinkers, were neither (as many of them supposed) the way

all humans can be expected to behave in the State of Nature. Instead, certain

freedoms – to move, disobey, and rearrange social ties – tend to be taken for

granted by anyone who has not been trained explicitly into obedience (as anyone

reading this book, for instance, is likely to have been). Still, the societies that European settlers

encountered only really make sense as the product of a specific political

history: a history in which questions of hereditary power, revealed religion,

personal freedom, and the independence of women were still very much matters of

self-conscious debate.

Tianyuan Man, from near present-day Beijing, and Hòabìnhian people, from present-day Laos and Malaysia,

represent two very old lineages that are distinct from today’s East Asians.

The sequences from ancient DNA were extracted from the leg bones of the Tianyuan Man,

a 40,000-year-old

individual, and

discovered near a famous paleoanthropological site in western Beijing. One of the earliest modern

humans found in East Asia, his genetic sequence marks him as an early ancestor

of today’s Asians and Native Americans. That he lived where China’s current

capital stands indicates that the ancestors of today’s Asians began placing

roots in East Asia as early as 40,000 years ago.

Farther south, two 8,000- to 4,000-year-old

Southeast Asian hunter-gatherers from Laos and Malaysia associated with the Hòabìnhian culture have DNA that, like the Tianyuan Man, shows they’re early ancestors of Asians and

Native Americans. These two came from a completely different lineage than the Tianyuan Man, which suggested that many genetically

distinct populations occupied Asia in the past.

But no humans today share the same genetic makeup as

either Hòabìnhians or the Tianyuan

Man, in both East and Southeast Asia. Why did ancestries that persisted for so

long vanish from the gene pool of people alive now? Ancient farmers carry the

key to that answer.

Rice farmers, possibly from around the Yangtze River,

moved south into Southeast Asia, while millet farmers from around the Yellow

River moved north into Siberia:

Based on plant remains found at archaeological sites,

scientists know that people

domesticated millet in northern

China’s Yellow River region about 10,000 years ago. Around the same time,

people in southern China’s Yangtze River region domesticated rice.

Because their archaeology and morphology was different from that of the Yellow River

farmers, we had thought these coastal people might come from a lineage not

closely related to those first agricultural East Asians. Maybe this group’s

ancestry would be similar to the Tianyuan Man or Hòabìnhians.

Today’s northern and southern Chinese populations

share more in common with ancient Yellow River populations than with ancient

coastal southern Chinese. Thus, early Yellow River farmers migrated both north

and south, contributing to the gene pool of humans across East and Southeast

Asia.

The coastal southern Chinese ancestry did not vanish,

though. It persisted in small amounts and did increase in northern China’s Yellow River region

over time. The influence of

ancient southern East Asians is low on the mainland, but they had a huge impact

elsewhere. On islands spanning from the Taiwan Strait to Polynesia live

the Austronesians, best known for their seafaring. They possess

the highest amount of southern East

Asian ancestry today,

highlighting their ancestry’s roots in coastal southern China.

Other emerging genetic patterns show connections between Tibetans and ancient

individuals from Mongolia and northern China, raising questions about the

peopling of the Tibetan Plateau.

Ancient DNA reveals rapid shifts in ancestry over the

last 10,000 years across Asia, likely due to migration and cultural exchange.

Until more ancient human DNA is retrieved, scientists can only speculate as to

exactly who, genetically speaking, lived in East Asia prior to that.

But what happened on land also span the oceans,

thus 3000 years ago that humans first set foot on Fiji and other isolated

islands of the Pacific, having sailed across thousands of kilometers of ocean.

Yet the identity of these intrepid seafarers has been lost to time. They left a

trail of distinctive red pottery but few other clues and scientists have

confronted two different scenarios: The explorers were either farmer who sailed

directly from mainland East Asia to the remote islands, or people who mixed with

hunter-gatherers they met along the way in Melanesia, including Papua New

Guinea.

Recently, the

first genome-wide study of ancient DNA from prehistoric Polynesians has

boosted the first idea: that these ancient mariners were East Asians who swept

out into the Pacific. It wasn't until much later that Melanesians, probably

men, ventured out into Oceania and mixed with the Polynesians.

And coming back to our

starting point as we have maintained from the beginning Anatolia was

home to some of the earliest farming communities. It has been long debated

whether the migration of farming groups introduced agriculture to central

Anatolia. Here, we report the first genome-wide data from a 15,000-year-old

Anatolian hunter-gatherer and from seven Anatolian and Levantine early farmers.

We find high genetic continuity (~80-90%) between the hunter-gatherers and

early farmers of Anatolia and detect two distinct incoming ancestries: an early

Iranian/Caucasus related one and a later one linked to the ancient Levant.

Finally, we observe a genetic link between southern Europe and the Near East

predating 15,000 years ago. Our results suggest

a limited role of human migration in the emergence of agriculture in central

Anatolia.

That indigenous doctrines of individual

liberty, mutual aid, and political equality, which made such an impression on

French Enlightenment thinkers, were neither (as many of them supposed) the way

all humans can be expected to behave in the State of Nature. Instead, certain

freedoms – to move, disobey, and rearrange social ties – tend to be taken for

granted by anyone who has not been trained explicitly into obedience (as anyone

reading this book, for instance, is likely to have been). Still, the societies that

European settlers encountered only really make sense as the product of a

specific political history: a history in which questions of hereditary power,

revealed religion, personal freedom, and the independence of women were still

very much matters of self-conscious debate.

Göbekli Tepe revisited part four will address

subjects like why and in what context did cave paintings (discovered

in late 2017) like the following pig appeared at least

45,500 years ago in what is now Sulawesi Indonesia. Whereby the suggestion

was that they are signs of those who first migrated down the

Indonesian island chain and onto the northern tip of Australia some 65,000

years ago.

1. Dorian Q.Fuller,‘Contrasting

patterns in crop domestication and domestication rates: recent

2. For China see Anne P. Underhill

et al, ‘Changes in regional settlement patterns and the development of complex

societies in southeastern Shandong, China.’ Journal of Anthropological

Archaeology 27 (1),2008, 1–29; for Peru see RuthSolis,,

Jonathan Haas and Winifred Creamer. ‘Dating Caral, a Preceramic site in the

Supe Valley on the central coast of Peru.’ Science 292 (5517), 2001,

723–6.

3. On ‘Early Bronze Age urbanism and its

periphery’ in western Eurasia see Andrew. Sherratt, Economy and

Society in Prehistoric Europe. Changing Perspectives. Edinburgh: Edinburgh

University Press,1997, 457–70; and more generally, James C.Scott’s, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the

Earliest States. New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press,2017, 219–56,

'reflections on ‘The golden age of the barbarians’.

4. This pattern much resembles Max Weber’s

famous notion of ‘the routinization of charisma, where the vision of a

‘religious virtuoso’, whose charismatic quality was based explicitly on

presenting a total break with traditional ideas and practices, is gradually

bureaucratized in subsequent generations. Weber argued that this was the key to

understanding the internal dynamics of religious change.

5. Kroeber (1944: 761) began his grand

conclusion as follows: ‘I see no evidence of any true law in the phenomena

dealt with; nothing cyclical, regularly repetitive, or necessary. There is

nothing to show either that every culture must develop patterns within which a

florescence of quality is possible, or that, having once so flowered, it must

wither without chance of revival.’ Neither did he find any necessary relation

between cultural achievement and systems of government.

6. In their additional cultic role as

the ‘god’s hand’ the wives of Amun – such as Amenirdis I and Shepenupet II – were also obliged to assist the male

creator-god in acts of cosmic masturbation; so, in ritual terms, she was as

subordinate to a male principal as one could possibly imagine, while in reality

running a good portion of Upper Egypt’s economy and calling political shots at

court. Judging by the grand locations of their funerary chapels at Karnak and Medinet Habu, the combination made for some very effective

realpolitik.

7. See John Taylor’s chapter on ‘The

Third Intermediate Period’ in Shaw (ed.) 2000: 330–69, especially 360–62.

8. Schneider 2008: 184. 37. In The

Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Shaw ed. 2000), for instance, the relevant

chapter is called ‘Middle Kingdom Renaissance (c.2055–1650 BC).’

9. In The Oxford History of Ancient

Egypt (Shaw ed. 2000), for instance, the relevant chapter is called ‘Middle

Kingdom Renaissance (c.2055–1650 BC).

For updates click homepage here