By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The humiliations at the hands of foreign

powers narrative

According to Social Identity

Theory, a significant part of an individual's personal identity consists of his

or her social identity, and so depends on group membership. Group identity

tends to be defined by contrast to other groups. Membership in a group leads to

systematic comparison, differentiation, and derogation of other groups. In

conflicts between groups of people, disputants usually view people outside

their own group as less good, or in the case of the opposing group, as really

bad. The opposing group is seen as the "enemy," who is inferior to

one's own group in many ways. When people are engaged in a serious

conflict, they will normally project their own negative traits onto the other

side, ignoring their own shortcomings or misdeeds, while emphasizing the same

in the other.

Enemy images and

stereotypes are formed in response to the basic human psychological need for

identity, and as a result of group dynamics. Once a conflict becomes escalated

and polarized, enemy images are bound to be formed. This sort of inter-group

conflict occurs even in the absence of material bases for conflict. Enemy

images play an important role in perpetuating and intensifying conflict.

The zero-sum nature of face and China's history of

victimization at the hands of the West combine to make many contemporary

Chinese view diplomacy as a fierce competition between leaders who win or lose

face for the nations they embody.

Public apology

however means admitting a fault. Clinton’s full apologies and Bush’s (as

translated by the Chinese) full apologies-were skillfully “dressed up” by the

Chinese official media as diplomatic victories of Beijing. The American

apologies were also used by Beijing to put itself on the “moral high

ground”-“We are right” and “You owe us.”

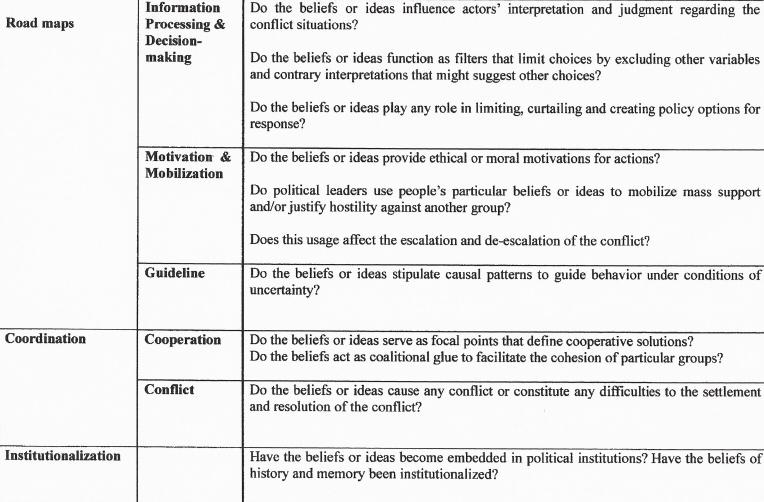

The following now is

designed to examine how, the beliefs of history and memory influenced the

Party’s decision-making during the three incidents we promised to make sense

of.

In the eyes of many

Americans and international observers, issuing Taiwanese President Lee the visa

to deliver the graduation address at his alma mater was innocuous, the 1999

embassy bombing was merely a technical mi stake and the U.S. government offered

official apologies fully and quickly, and the 2001 plan collision happened

outside Chinese territorial waters, therefore, they would not think that any of

these incidents were intentional or any kind of bullying or aggression to China

or the Chinese people.

However, as we have

seen, the majority of Chinese people, including the majority members of the CCP

Politburo, believed that the embassy bombing was a deliberate action, an

American conspiracy; even though the EP-3 was outside Chinese territorial

waters, it was conducting spying against China, and the collision caused the

damage of Chinese jet and the death of Chinese pilot; therefore, they saw both

incidents as American aggression, many of them even viewed them as China’s new

humiliation, another in a long line of humiliations that China has suffered

since the Opium War. Why did people of the two parties have such huge

differences in perceptions and interpretations regarding the same conflict

situation?

The concepts of

security dilemma and enemy images provide alternative explanations for the

Chinese people’s perception of the United States. However, both concepts cannot

fully explain why the rise of anti-Americanism, especially the rising vigilance

and suspicions to the United States, happened at a time when China’s contacts

and exchanges with the U.S. have been greatly increasing. The rapid changes in

the context of US-China relationship and the development of globalization have

made the two countries more closely connected with other.

Like culture, history

and memory are rarely by themselves the direct causes of conflict, but they

provide the “lens” by which we view and bring into focus our world; through the

lens differences are refracted. The lens of historical memory helps both masses

and elites interpret the present and decide on policy. (See Kevin Avruch, Culture and Conflict Resolution, Washington D.C.,

1998).

Through this lens of

historical memory, an isolated and/or accidental event (as viewed by the

Americans) was perceived by Chinese leaders as a new humiliation. The disputes

in question, thus easily touched on sensitive Chinese feelings about Western

imperialist nations taking advantage of a weakened China in the 19th

and early 20th centuries.

History and memory

also provide individuals a reservoir of shared symbols that may be enlisted to

constitute contesting social groups. (See Allen Tidwell, Conflict

resolved? A Critical Assessment of Conflict Resolution, 1998).

Following the 1840

Opium War, China was on the verge of subjugation and loss of its

thousands-year-long national identity. The Eight-Power Allied Forces occupied

Beijing in 1900. Japan annexed Taiwan and Manchuria and occupied more than 900

cities from China. Hong Kong, Macao, and numerous small areas became concession

zones to foreign powers. The invasion by Western powers and Japan reduced China

to the status of semi-colonial society. The Chinese nation was facing a grave

threat to national survival.

As represented by

China’s national anthem, a very strong sense of crisis, or sense of insecurity,

has always been an important theme of the national political discourse in

China. Thus, the narrative of national salvation depends upon national

humiliation; the narrative of national security depends upon national

insecurity. There is a popular political slogan in China, “Never let the

historical tragedies be repeated.” The government therefore asks people to

always keep a wary eye on international “anti-China forces.” “Heighten our

vigilance and defend our motherland” is another political slogan that was

particular popular in China during the 1970s. Such kind of remarks on vigilance

as we have seen have now become a sign of being “patriotic” and “sober-minded”

for the speakers, and especially also during the three incidents we have

commented on.

The one hundred year

national humiliation has provided the current Chinese leaders a lot of

historical analogies to use and they often draw a parallel between a current

event and a historical event, as the previous sections have shown. A deep

historical sense of victimization by outside powers, a long-held suspicions

about foreign conspiracies against China, and the powerful governmental

education and propaganda campaigns on historical humiliation, all these have

worked together to construct a special Chinese “culture of insecurity.” Under

this mindset, international confrontations are easily perceived and experienced

by the Chinese as assaults on fundamental identity, dignity (face), authority

and power. They are also oversensitive to grievances of old (this nation’s

“chosen trauma”), which renders the country over prone to tantrums at the

slightest international offense, real or imagined.

Peter Hays Gries’

research on the embassy bombing supports the above analysis. As he wrote: “the

tales of the ‘Century of Humiliation’ which began with the First Opium War and

the renting out of Hong Kong to the British in 1842, powerfully shaped the way

that Chinese both interpreted and reacted to the Belgrade bombing.” The

“sense of victimization” and “suspicion syndrome” deeply affected Chinese

people’s attitudes, interpretation and judgment regarding the conflict

situations. (Gries, “Tears of rage: Chinese nationalist reactions to the

Belgrade embassy bombing,” China Journal, No. 46, July 2001, p. 26.)

But why did neither

Chinese leaders nor the Chinese people seem to believe that the bombing of the

Embassy was a technical mistake? Why are there widely-believed conspiracy

theories in China regarding U.S. intentions? As we have discussed in the

previous sections, history and memory constitute a powerful force over Chinese

people’s thought, feelings and action. As a result of the Patriotic Education

Campaign, many Chinese have begun to confront rather than avoid their past

humiliation.

The new focus on

Chinese misery during the “one hundred years of national humiliation” has given

rise to an outpouring of victim consciousness among the Chinese public. All the

three incidents fed into a renowned “Chinese sense 01 victimization,” of having

been the world’s greatest nation only to be humiliated in the 19th

and early 20th centuries. The accidental or mischievous behavior on

the part of the U.S. caused sufferings (e.g., the injuries and deaths), and

therefore touched on sensitive Chinese feelings about Western imperialist

nations taking advantage of a weakened China in the 19th and early

20th centuries.

Just as Chinese

leader Deng Xiaoping drew a parallel between the western economic sanctions in

1990 with eight powers’ invasion to China in 1900, so, according to Zhu Wengli’s research, when NATO started bombing Yugoslavia,

“the historical precedent the Chinese referred to was not the ethnic cleansing

against the Jews by Hitler as in the West, but the allied military intervention

during the Boxer Rebellion.” (Wenli, How Chinese see

America, paper presented at “China-U. S. Substantial China

Dialogue,” November 1, 2000.)

Clearly, historical

analogies function as important information processors. They help resolve

conflicting incoming information in ways consistent with the expectations of

the analogy.

Just as the Cuban

missile crisis was a “cultural production”, in which the official U.S. state

narrative marginalized alternative understandings of these events, so the three

US-China incidents were also “eultural produetions”. The Chinese official state narrative of past

humiliation, the “sense of victimization”, and “suspicion syndrome” both

constituted three incidents as crises and marginalized alternative

understandings.

In fact the central

myth of the ruling party today is that its historical “sacrifices and

contribution” have “put an end to the history of humiliating diplomacy in modem

China.” The legitimacy of current China’s rulers is thus highly dependent upon

successful performances on the international stage. The CCP leadership is

responsible for maintaining China’s “national face” in its dealings with other

nations. Therefore, whenever an international incident might be perceived

as a new humiliation, it immediately became a test for the ruling party. To

Beijing, each of the three incidents was much more than a simple violation of

Chinese sovereignty: it was seen as a test for the Party-not a test-of-will for

power competition, but a test of the ruling party’s legitimacy and “political

credibility.” The Chinese government needed to be able to show the people, the

public, that it would not allow humiliation again. Being tough and aggressive

thus became the natural choice of the Party. Otherwise, they would not pass the

“test.”

For all the three

crises, there existed other options for response, there were also some

international practices for handing these kinds of incidents. For example, a

“normal” response for handing the EP-3 plane collision accident could be that

the 24 crew members of the EP-3 would be allowed to return home in the first

several days, China might hold the plane and then the two countries start to

negotiate about compensation and settlement. For the embassy bombing, if the

same kind of incident happened between the U.S. and another country, it would

certainly arouse a very strong response in many countries of the world, even an

ally. Emotional demonstrations were almost certainly expected to happen.

However, for most countries, the demonstrations would be spontaneous, the

governments would not organize them and should also try their best to prevent

the protesters for destroying U.S. property or besieging the U.S. ambassador

and staff. Although the anti-American demonstrations in response to the bombing

were overwhelmingly voluntary, they were still indirectly endorsed by the

government: in a single-party regime, only the government would be able to

provide transportation, to loosen security procedures allowing the masses to

apply for demonstration permits, and to tacitly tolerate physical damage to the

US Embassy in Beijing.

Similarly, if the

decision that the Clinton administration made to issue Taiwanese president the

visa to visit the U.S. reversed a 16-year-old U.S. practice, diplomatic

protests, including even actions such as recalling ambassador could be choice

of options, but the responses should be kept in the diplomatic sphere. But

China’s responses in 1995 and 1996 were three rounds of large-scale

live-ammunition military exercises with ballistic missiles flying over Taiwan.

Table 6.2 is a summary of China’s conflict behavior during the three crises

contrasting with the hypothetical more “normal” diplomatic practice.

The historical memory

variable helps explain why Chinese leaders did not choose to resolve the three

incidents through cool diplomacy. When the incidents were perceived as

bullying, and when the central myth and the legitimacy of the government are

highly dependent upon maintaining China’s “national face,” it became natural

and understandable that the government needed to be “tough.” “Cool diplomacy”

would not pass the domestic test and therefore was eliminated as an option.

In case of the

embassy bombing the instrumental stakes were too high, and the assault on

Chinese self-esteem was too acute. Popular nationalists had taken to the

streets in protest, and Chinese diplomats were forced to take a public posture

of rejecting American apologies and explanations. Like a father refusing his

son’s repeated prostrations of forgiveness, rejecting America’s repeated

apologies was one of the few ways China’s leadership could seek to restore

Chinese self-esteem in the eyes of the Chinese people.

Through the lens of

historical memory, isolated and/or accidental events were magnified and

rendered emotional. Diplomacy between the two states therefore quickly became

games. Both Clinton’s full apologies and Bush’s two regrets—translated by the

Chinese as full apologies-were skillfully “dressed up” by the Chinese official

media as diplomatic victories. In the EP-3 ease, at the juncture when Beijing

could not get what they wanted (the full apology from the U.S.) and might lose

the competition, linguistic differences between the two countries were

creatively used to create a solution.

The three US-China

crises should also be understood in the context of the rising nationalism in

China after the June Fourth tragedy and the end of the Cold War. In the

previous part we discussed how the state-led “Campaign of Patriotic Education”

has promoted the “national humiliation education” and greatly contributed to

the rise of nationalism in China. The rise of nationalism did help Beijing to

regain its ethical and moral legitimacy.

The communist party

dressed itself up as a nationalist party ever since the end of the Cold War and

the collapse of “international” communism. The three incidents cut “perfectly”

into the emerging “victimization narrative’ in China and thus provided the fuses

to touch off Chinese popular nationalism. However, the rise of nationalism is

also a double-edge sword. During all the three crises, the government not only

negotiated with the U.S. government, but had to “negotiate” with its domestic

audiences too. The rise of nationalism put pressure on the government’s

policy-making. The government needed to be tough to maintain its legitimacy.

Through the lens of history and memory, the three events were perceived and

experienced by the Chinese as assaults on fundamental identity, dignity (face),

authority and power. The beliefs of history and memory thus justified the

escalation of the conflict and the course of its development. Being tough and

aggressive thus had ethical and moral correctness. This helps to explain why

many of Chinese government’s actions in external affairs are regarded as

“harsh” by foreigners but perceived as “soft” by much of its domestic audience.

And finally, the

three crises share a striking similarity. Escalation from an international

incident or accident to a serious crisis was in each case caused by China’s

unexpectedly strong reaction to accidental or mischievous behavior on the part

of the U.S. In other words, it appeared as if China intended to escalate the

crisis. Oddly, however, at the same time during the course of each crisis,

China also desired to develop a better bilateral relationship. The collapse of

communism in Eastern Europe, especially the overthrow of the Romanian regime,

has had a particularly chilling effect on Chinese leaders. The subsequent

sanctions and pressures from the West have further added to Beijing’s anxiety

and nervousness. In general, China’s leadership in the 1990’s has tried hard to

avoid direct conflict with the West, particularly the United States-in contrast

to Mao’s approach. China’s leaders in many cases have adopted moderate stances

on many occasions, and at times even submitted to what they considered insulting

demands. For example, China allowed the United States to search publicly its Yinhe vessel for chemical weapons in 1993, even though

there were no such weapons on board. China also began to cooperate with the US

in the field of arms control, agreeing to join the Nuclear Nonproliferation

Treaty (NPT) in 1991, acceding to the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR)

in 1992, and agreeing to join the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) in 1996.

China has steadfastly attended multilateral negotiations on arms control and

disarmament, and has signed or ratified almost all the multilateral arms

control treaties, making a positive contribution to the progress of

international arms control and disarmament. China signed the WTO entry

agreements with U.s. even though many of its domestic

critics drew parallel between the WTO treaties with those ‘unequal treaties”

that the Qing Dynasty signed with the western powers one hundred years ago. Why

did China cooperate with the U.S. in the same period of time on some issues but

turn aggressive on these other issues?

To answer this

question, it is necessary to compare the three non-conflict US-China events

(WTO Negotiations, Arms Control Negotiations and the Yinhe

Incident) with the three conflict cases (1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis, Embassy

Bombing Crisis and the EP-3 Crisis). To put the first three cases into the

category of “non-conflict” does not mean there were no disputes or

confrontations in the three cases. The US-China WTO Negotiations, for example,

took thirteen years and experienced many setbacks and serious disputes during

the processes. However, China’s main approach of handling the three events was

cooperative, trying hard to avoid the escalation of conflict. There was also

some cooperation between the two states during the three conflict incidents.

For example, as we discussed earlier, at the last stage of the EP-3 crisis, the

two governments, somehow were cooperating tacitly with each other to. But yet

in all the three cases, China intentionally escalated the crisis.

One similarity

uniting all the six cases was they concerned sovereignty issues. The WTO

negotiations and the arms control negotiation were about China’s two vital

interests: trade and security. The six cases have three major differences:

(1) Emergency

The WTO negotiations

and the arms control negotiation both involved long processes. But the other

four cases happened suddenly as emergencies. Five 2000-pound Joint Direct

Attack M4J1itions (JDAMs) attacked the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade on May 7,

1999; On April I, 2001, a V.S. EP-3 Aries 11 airplane collided with a Chinese

F-8 fighter jets and made an emergency landing on China's Hainan Island at Lingshui; The Clinton administration unexpectedly made a

decision to issue Taiwanese President Lee Teng-hui the visa to visit the United

States; On July 23, 1993, the CIA alleged that a Chinese container ship, the Yinhe, was carrying chemical weapons material to Iran and

three U.S. military ships began to chase Yinhe in the

public sea. Meanwhile U.S. pressure persuaded Gulf countries not to permit the

ship to dock, unload cargo, or take on fresh food and water for twenty days.

(2) Public awareness

The Chinese Communist

Party maintains a tight control of all the media in China. Public awareness of

a particular international incident therefore is dependent on whether the Party

allows the media to report this event or not. However, for some international

crises or emergencies that happened in China, especially the events with

casualties and injuries, it is difficult for the Party to hide them, even

though the Party can still control the flow of information and filter the news.

For example, the embassy bombing happened at midnight on May. 8, but the

Chinese official media did not report it until noon of the next day. The media

did not report Bill Clinton's first apology on May 8 because the government

needed to flame the public' s hatred at the early stage of the crisis. During

the 1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis, Beijing actually carried out a media blitz

against the U.S. and the Taiwanese leader. The EP-3 Incident was called

"Spy Plane Incident" in Chinese media. The official media gave

detailed reports about the accident and why it was the EP 3's fault, as well as

and the humanitarian treat that China provided to the V.S. crew members.

For the 13-year WTO

negotiations and the 6-year arms control negotiations, the Chinese people were

aware of the ongoing negotiations between the two countries. However, they did

not know about any detail about theses negotiations.

For example, even today, ordinary people do not have access to the WTO treaties

the two countries signed, even though some of them have changed their courses

of life. For most Chinese people, the Yinhe Incident

is an unheard name. There were almost no official reports about this event.

Why?

First, this incident

did not happen inside China, so the government could hide it from public

awareness; second, for the first one or two weeks, the government itself was

not quite sure whether there were chemical weapons material in this container

ship or not; third, if the media were allowed to report it, the public might

think it was a humiliation to China for allowing the U.S. to conduct an open

inspection of this Chinese ship.

(3) Negotiation mode

All the six cases

involved negotiations and finally were settled that way. But there were

differences in the negotiation modes that distinguish the three non-conflict

cases from the three cases of escalation. The negotiations of "the first

type were conducted mainly among the professional experts of the two countries.

For example, the Chinese team participating in the arms control negotiations

was composed of nuclear experts, officials from the Arms Control Bureau of the

Foreign Affairs Ministry and scholars on arms control issues from government

think tanks. The Yinhe Incident was negotiated solely

by the officials of the Arms Control Bureau of the Foreign Affairs Ministry.

The negotiations of the other type, however, were meanly political and very

public. Not only were the diplomats of the two involved, but also the military,

the U.S. congress and even the media were indirectly involved in the talks. The

top leaders of the two countries made open statements and exchanged letters

during the processes.

The three U.S. China

crises were actually China's only "hot" conflicts with foreign

countries after the end of the Cold War. However, during this period of time,

China had territorial disputes with some ASEAN countries. In the late 1990s, as

a new strategy of strengthening their territorial claims, Philippines and

Vietnam took the lead to intensify the situation by seizing and attacking

Chinese fishermen and fishing boats in the South China Sea. However, the

Chinese government demonstrated a very restrained response to these

provocations. In 1998 too, Chinese government expressed only verbal concern but

did not take any actions during the massive anti-Chinese riots in Indonesia. It

seems that China treated different countries differently when dealing with conflicts.

Comparing the above

mentioned three non-U.S. cases with the three US-China Crises, the six cases

share three important similarities:

(5) Each of them

involved Chinese casualties and injuries. Compared with the three US-China

crises, the Chinese casualties and injuries were even much bigger in the three

non-U.S. cases. For example, Indonesia's ethnic Chinese were the main target of

the bloody Jakarta riot in May 1998. According to Indonesian government

sources, over 1,000 Chinese people died during these riots, many women were

raped, 2,479 shop-houses, 1,026 ordinary houses, 1,604 shops, 383 private

offices, 65 bank offices were destroyed. (http://en.

wikipedia.org/wiki/Indonesian _1998_ Revolution)

(6) All of them were

emergencies. The leaders had to make decision quickly.

(7) Each of them was related

to sovereignty issues. The South China Sea disputes were about territory. Even

though the Indonesian ethnic Chinese are no longer citizens of People's

Republic of China (China does not accept dual citizenship), however, supporting

and protecting citizens who live abroad should be the responsibility of any

state.

For the public, the

Chinese official media did report about the South China Sea disputes and the

Indonesia riots, but without providing any details. During the Indonesia riots,

many photos of the riots were spread on the Internet. Some Chinese people, mainly

students and intellectuals who had access to Internet, strongly criticized the

government for being cold and detached toward overseas Chinese.

For updates

click homepage here