By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

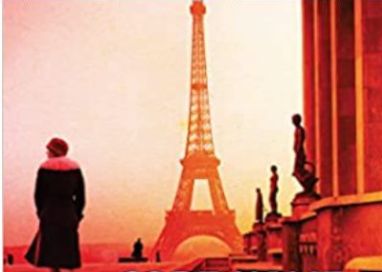

Codename Madeleine

At the beginning of WWII, with Britain becoming desperate,

Churchill orders his new spy agency—the Special Operations Executive (SOE)—to

recruit and train women as spies. Their daunting mission: conduct sabotage and

build a resistance. SOE's "spymistress," Vera

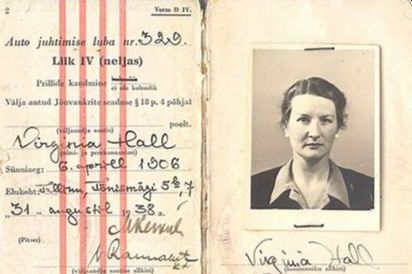

Atkins (Stana Katic), recruits two unusual candidates: Virginia

Hall (Thomas), an ambitious American with a wooden leg.

And as detailed below Inayat Khan (Radhika Apte), an

Indian Muslim pacifist.[1] Together, these women help to undermine the Nazi

regime in France, leaving an unmistakable legacy in their wake.

In January, U.K.

broadcaster Sky History acquired “Liberté” which tells the true story of

Noor Inayat Khan, the daughter of a Sufi preacher and an American, who became a

France-based spy and radio operator for the British during the war, something we

follow up on underneath.

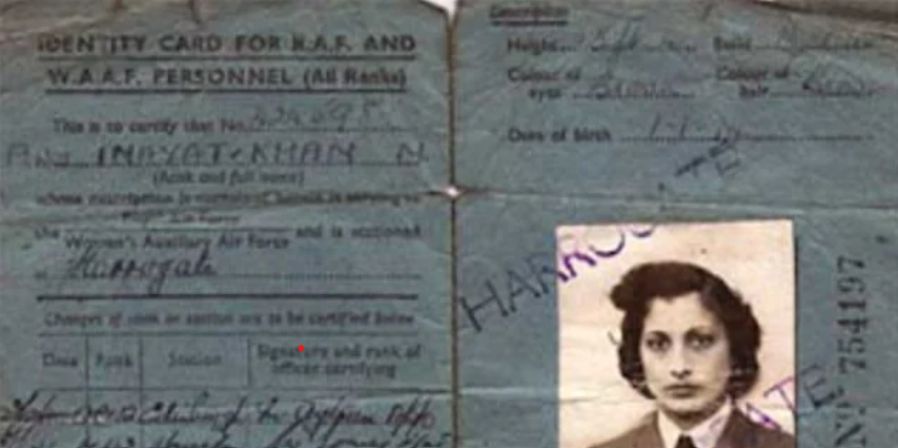

Noor Inayat Khan,

also known as Nora Inayat-Khan and Nora Baker, was a British resistance agent

in France in World War II who served as the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

Many years ago, we posted extensive coverage of both The Political Warfare

Executive (PWE) And The Special Operations Executive

(SOE'), to which the subtitle The Special Operations Executive

below is intended as a brief update.

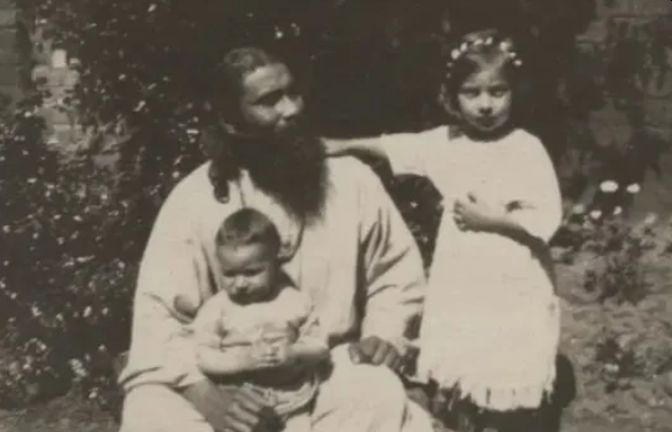

Noor Inayat Khan was

born on 1 January 1914 in Moscow. She was the eldest of four children.

Her father was Vilayat Inayat Khan, an author, and Sufi

teacher; Hidayat Inayat Khan, a composer, and Sufi teacher.

Her mother, Pirani

Ameena Begum (born Ora Ray Baker), was an American. from Albuquerque, New

Mexico, who met Inayat Khan during his travels in the United States. Afterward,

Vilayat became head of the "Sufi Order of the West," later renamed

the Sufi Order International, and now the Inayati Order.

In 1914, shortly before

the outbreak of the First World War, the family left Russia for London and

lived in Bloomsbury. Noor attended nursery in Notting Hill. In 1920,

the family moved to France, settling in Suresnes near Paris.

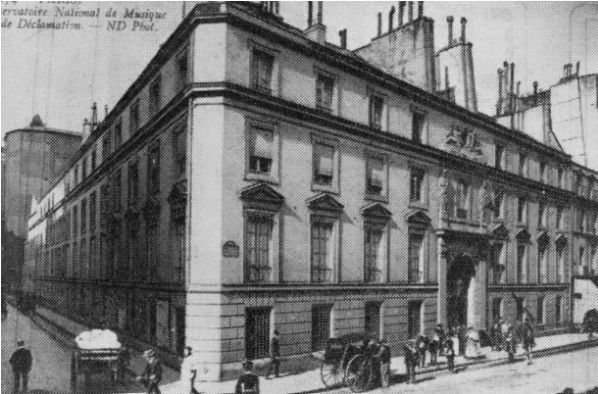

Noor was earnest

about feeling for music and went to the Paris Conservatory to learn

music professionally.

She learned to play the harp and piano and composed

music before long.

Noor may have loved

music, but she had other dreams and interests too. She was studying Child

Psychology at the Sorbonne at the same time that she was pursuing her musical

passions, so who knows? It’s possible she planned on working as a psychologist

while playing music for herself. Or maybe she was trying to keep her options

open.

Although the whole

family mourned Inayat Khan’s passing, his wife took the loss, especially to

heart. She confined herself upstairs, refusing to come down or meet anyone.

Noor had to step up and assume a maternal role for her three younger siblings.

And that was just the

beginning of her journey. In 1940 when France fell to Nazi Germany, Noor fled

to Britain with her family.

The Special Operations Executive

The Special

Operations Executive (SOE) was a secret British organization created during the

Second World War to encourage resistance and carry out sabotage in enemy

territory. It was formed in July 1940 by the amalgamation of three

existing organizations.

One of these was

Section D, part of the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS, also known as MI6).

Set up under Major Laurence Grand of the Royal Engineers, Section D had been

planning clandestine sabotage and propaganda operations to undermine the German

economy since 1938.

The second of SOE’s

forebears was Military Intelligence (Research), a ‘think-tank’ in the War

Office tasked with studying and planning irregular warfare projects. In charge

of MI(R) was another Royal Engineer, Major J.C.F Holland. The third

organization was Electra House, a Foreign Office secret propaganda operation

created after the Munich crisis.

Britain’s new Prime

Minister, Winston Churchill, was enthusiastic about the concept and, at the

outset, placed Hugh Dalton, the dynamic socialist Minister of Economic Warfare,

in charge of SOE. According to Dalton, Churchill commanded him to ‘set Europe ablaze!’

This stirring quotation has come to be seen as Churchill's founding command to

SOE. The less dramatic but official definition of SOE’s role was 'to coordinate

all action, by way of subversion and sabotage, against the enemy overseas’. By

the war's end, SOE’s role was global (though naturally, its early and principal

thrusts were in the Axis-occupied territories of Europe and

the Middle and Far East).

SOE’s principal headquarters

was at 64 Baker Street in London; as the war progressed, it took over many more

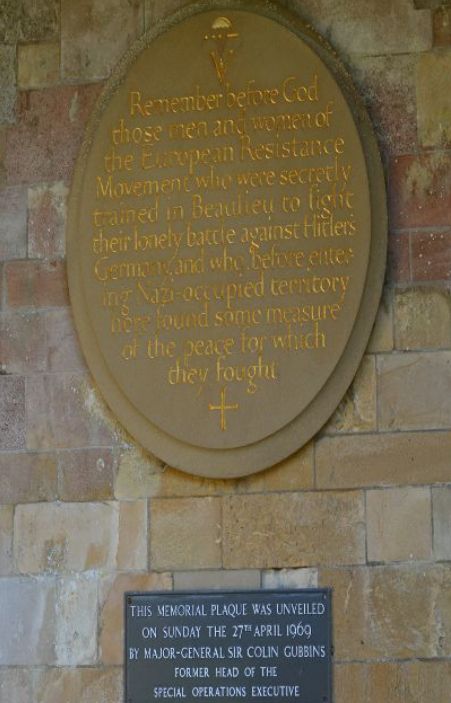

buildings in surrounding streets. Training and holding schools were also

established to prepare candidates recruited as prospective agents. In Britain,

many of these schools were requisitioned country estates and houses:

paramilitary training took place in the Scottish highlands, for example, and

parachuting was taught at Ringway, now Manchester airport, while SOE’s famous

‘finishing school’ for agents occupied several houses on the Beaulieu estate in

Hampshire.

Other premises acted

as the wireless stations by which SOE kept in contact by radio with its agents

in enemy territory. Research establishments were also devoted to developing new

equipment, methods, and devices for sabotage and clandestine warfare, from

silenced pistols to time-delay detonators.

Other headquarters

and training schools were also established overseas. Operations into the

Balkans, for example, were chiefly planned and directed from the Middle East

and, later, Italy. India and Ceylon were the main bases for operations into

Burma and Malaya. Many operations into Borneo and other Japanese-occupied

territories were planned and launched from Australia.

Many SOE operations

aimed to undermine the enemy's military, economic and industrial strength by

targeting raw materials, industry, communications, and supply lines. Among its

most famous exploits was the successful sabotage in 1943 of the Norsk Hydro ‘heavy

water’ plant at Vemork in Norway by a team of

Norwegian SOE agents; the operation was aimed at disrupting German attempts to

develop an atomic bomb.

SOE also played an

essential role in supporting and coordinating local resistance groups to divert

enemy attention from the significant fighting fronts. In France, for example,

the German Das Reich Division, ordered to reinforce the German forces in Normandy

after D-Day, was delayed in its journey from the Toulouse area for a critical

seventeen days by SOE-backed ambushes and sabotage. Altogether, SOE put 10,000

tons of warlike stores into France alone: 4,000 of them before and 6,000 after

D-Day; by 6 June, it also had some fifty wireless links to French resistance

movements.

Arguably one of SOE’s

most important contributions was its ability to encourage and fuel a spirit of

resistance among Axis-dominated populations, which remains a source of enduring

national pride and inspiration in many corners of the world.

At the dawn of World

War II, Winston Churchill, the former PM of UK ordered his new spy agency to

train women for covert operations as there was a shortage of men. Aged 26, Noor

became a radio operator and the first woman wireless operator to be sent to Nazi-occupied

France. She went undercover and worked in France for three months to set up

crucial links and send information back to London.

Codename Madeleine

When Mark B.

Fuller walked onto a podium. Seated before him were forty young women in

uniform, SOE’s army of codebreakers. The title of Marks’s address was: ‘There

Is No Such Thing as an Indecipherable Message.’ He looked at the upturned faces

of forty female codebreakers. Marks had never considered cryptography to be the

most seductive part of the war, but the women sat in rapt attention and made

him feel, for once, like an Apollonian Spitfire pilot.

Marks gave

well-chosen examples of Station 53a being ‘Undefeated in Difficulties’:

codebreakers attacking mutilated codes through the night to find epiphany at

dawn. He recalled instances of codebreaking that had saved lives. The end of

his talk was met with rapturous applause. Marks took questions from the

audience. As the meeting dispersed, a few codebreakers queued to ask more

informed questions. One was blonde. She wrote down his pearls of wisdom in an

exercise book. Each time she looked up, she shone her eyes on Marks as if he

were a rare animal. After the blonde closed her exercise book and walked away,

looking over her shoulder, the ground under Marks’s feet started to shake. It

was the codebreaker behind it. She stood with Cleopatra-black hair, animated

dark eyes and olive skin. She introduced herself as Ruth.

The full moon was

approaching. The next batch of F-Section agents was undergoing final

preparations for their drop. One was a harpist. The night before she left

Beaulieu, Noor Inayat Khan sat cross-legged beside her bed. She closed her eyes

and began the descent.

Marks sat reading the

file on the agent he was due to brief. The agent’s details were intriguing.

Gender: Female. Codename: MADELEINE. Education: Sorbonne. Former occupation:

Children’s author. Original unit: WAAF. Agent status: Wireless operator. Proficiencies:

Morse code, pistol marksmanship, unarmed combat. Special attributes: Harpist.

Religion: Sufi

Muslim. Next of kin: Amina Begum (mother). Her name was Noor Inayat Khan.

Marks’ cryptographer’s instincts were piqued. She was a puzzle. It was time to

assemble the pieces.

They met whenever

Ruth could escape on leave. She had studied archaeology at University College,

London. She had done a Ph.D. in deciphering Linear B. She could hold her own

with Marks on any subject, from poetry to cryptoanalysis. Marks even dared to

think about what they would do after the war.

Marks was at his desk

in Baker Street when there was a knock at the door. A bespectacled secretary in

a cardigan put her head around the door. ‘Agent Khan is here for your twelve

o’clock, sir.’

‘I am going to circle

five words to make the key,’ said Marks. ‘The first letters of each word will

become your indicator group.’ Marks wrote out the coding key at the top of the

squared paper and a twelve-word message in plain text.

The Drop Will Be North Of Paris At The Next Full Moon.

The following day,

Noor returned. Everything about her spoke of purpose.

Marks gave her six

passages to code. She took up her pencil and started work. Twenty minutes

later, six passages were in code. Marks looked over the codes. Something,

please, Yahweh, to prevent her from going. Her coding was perfect. With any

other agent, this was cause for celebration. In Noor’s case, it made Marks’s’s heart sink. ‘What about your bluff check and true

check?’ said Marks. ‘We were taught about both at Beaulieu. A bluff check means

the operator is transmitting freely. Inclusion of the true check means the

operator is transmitting under duress.’ ‘Correct.’ Noor smiled.

‘But who knows how

one’s mind works if it all kicks off? So I am going to give you a system that

is unique to you. If you transmit a message that is eighteen characters long,

you are operating under duress.’

‘Eighteen?’ said

Noor. ‘That’s my lucky number.’ ‘Mine too,’ said Marks. ‘It’s the code for

life.’

Marks signed off

F-Section’s only harpist as code-ready. He frowned. A quartermaster handing out

weapons that might explode during handling? It was time to put on his surgeon’s

gloves and take a scalpel to the entire poem-code system.

‘Never accept the

received view on anything. If something is so, why is it so? Test it. If it

fails the test, replace it with something better.’

The system was

devised shortly after SOE was formed. The rationale was that the agent did not

have to carry encryption keys. Memorized poems were invisible. That was fine if

the enemy did not have saws, pliers, and truth serum. The other problem was

that mistakes might be made if an agent was transmitting quickly under

challenging circumstances. There was also the problem of ‘Morse mutilation’ –

an indecipherable message would be transmitted sooner or later. Why? Because

mused Marks, the agent was in a hurry or made a mistake coding the message into

Morse. Or worse, the agent was transmitting under duress. That was why so many

messages required the coders of Grendon.

There was, however,

one anomaly. Holland. Since the first SOE agent was dropped into Holland, all

messages had come through loud and clear. No agonizing dissection at the hands

of the Grendon coders. It was a clue to catching the attention of even the most

preoccupied detective.

The Dutch agents were

on the low dark verge of life. Captured. The Abwehr used their radios to

spoon-feed Baker Street, a stroopwafel of false

intelligence. If there was a Eureka moment in Marks's life, this was it. Marks

fed a sheet of paper into his typewriter and tapped out the title.

Insecurities Of The Soe Poem Code

A plan formulated in

his mind over the next few days. It was vintage Marks, but it was not without

its risks. He would feed the Abwehr some of their stroopwafel.

Before leaving for a meeting in Duke Street with the French

government-in-exile, he left instructions for a message of sixty-four

characters to be transmitted to Agent Boni in Holland. Sixty-four seemed as

good a number as any from No. 64 Baker Street. The message was an intricate

concoction of gobbledygook. An Indecipherable. If the Abwehr controlled Boni’s

radio, how would they deal with something unexpected? The ultimate spin ball.

Marks smiled as he imagined the looks on the Abwehr’s faces.

‘The chief wants to

see you,’ said Captain Owen, poking his head round the door. Something in his

expression made Marks think it was not a courtesy call. Marks entered Gubbins’

office. It was obvious that something was wrong.

Gubbins sat in

silence. The samurai swords on the wall glinted. The crossed swords on Gubbins’

shoulder flashes sharpened in response. The brigadier held a memo in his hands.

His face was pale, the glass of his word.

‘Sit down, Marks,’

said the brigadier. ‘The answers you give me will be the truth, the whole

truth, and nothing but the truth. Do you understand?’

‘Yes, sir,’ said

Marks.

‘SOE message Number

59 transmitted to Dutch agent Boni in 64 characters was indecipherable. I have

reason to believe it emanated from you. And that it was deliberate.’

‘Guilty,’ said Marks.

‘Both charges.’

‘And since when,

Marks, do members of this organization act outside their orders?’

‘I had reason to

believe Agent Boni has been captured.’

‘Did you,

Marks?’

Gubbins was a small

man with large lungs.

‘DID YOU?’

‘Yes, sir,’ said

Marks.

‘Did you deign to

share your theory with anyone, Marks? Or did you go on a frolic of your own?’

‘I did not share my

theory, sir. But I drafted a report.’

‘You drafted a

report?’

‘I did, sir.’

‘And where is this

report, Marks?’

Marks found himself

racing through SOE headquarters like a hare on amphetamine. He returned, report

in hand. As Gubbins scanned each page, brow taut, Marks remembered he had left

in the footnote. Gubbins looked up after turning the final page. The room was

silent, save for breath.

Marks kept a low

profile for the next three months. Rumors went around SOE that he had done

something so bad it was good. It gave him an unexpected cachet. Marks said

nothing. He concentrated on his codebreaking. A penance. He made himself

invaluable to SOE and Grendon Hall, whatever the hour. He played chess against

himself over lunch and did what he was told.

On a crisp blue

afternoon, a letter arrived addressed to Leo Marks Esq., c/o The Ministry of

Economic Warfare, 64 Baker Street, London NW1. It was written in a clear hand.

The stamp was Highgate, London.

It was from Ruth’s

father. Each word ached with pain and dignity. The writer’s sad duty was to

pass on that Ruth had been killed in a plane crash. The transport plane she was

traveling on crashed after taking off from Toronto Airport. There were no survivors.

There would be a funeral as soon as her remains were repatriated.

Ruth was Leo Marks’

girlfriend in WW2.

Admiral Canaris and Stewart Menzies

There was a good

reason. Admiral Canaris was now fighting a war on two fronts. The previous

month he had received two top-secret intelligence reports for the eyes of

Admiral Canaris only. The first was from an Abwehr agent inside the Vatican.

The other was from an informant within the SD. An elite Gestapo detachment was

on its way to Rome. Their mission was complex yet simple. To kidnap the pope.

The ransom? Nazi domination of the world. And it was unlikely Hitler was

ignorant of the plan.

On receiving the

reports, Canaris sat with his face in his hands. The Nazis were not just

ruthless. They were mindless. And Godless. Canaris oversaw the transmission of

an immediate warning to a staunchly Catholic Italian general. The Vatican’s

Swiss Guard was alerted, and His Holiness was evacuated.

Germany faced an

enemy from within and without. From within, the man with the black nosebleed

and his Gestapo coven. From without the prospect of invasion. Sooner or later,

the Allies would muster in England and sweep across the Channel into France.

From France, they would move east. It would be the opening of the war in

reverse. This time Berlin, not Paris, would be surrounded and suffocated. Which

front would Canaris attack first?

By the end of dinner,

Canaris was the only guest in the art deco dining room.

A young man entered

the room at ten-thirty. He walked over to the table. He was fair for a

Spaniard. ‘Está ocupado este asiento…? Is this seat taken…?’

The men spoke until

midnight over coffee and port. When the bill was presented, the younger man

insisted on paying.

‘With the compliments

of Sir Stewart,’ he said.

Canaris smiled.

‘Please return my

compliments. I look forward to our speaking direct.’

The two men stood and

shook hands. The younger man left. Canaris sat for a moment in thought. A

patriot must protect his country from its government. He knew it paid to start

at the top, whatever the danger to his own life. Especially when dealing with someone

who considered the Admiral a potential caretaker leader if Germany sued for

peace. ‘Sir Stewart’ was Sir Stewart Menzies, head of Britain’s MI6.

Angers, France

1943 The words

crackled over the radio.

‘Jasmin joue de la flûte’ – ‘Jasmine is

playing her flute.’

London was calling.

A crackle of

excitement spread around the dinner table. Four agents would be dropped the

following night. The Resistance group huddled in Monsieur Linville’s basement

went into immediate action. Within twenty-four hours, everything would be

assembled. Torches, batteries, blankets, bandages, binoculars, petrol, Sten

guns, revolvers, coffee, Armagnac, several bottles of Chinon,

and – most importantly – a corkscrew.

London, 1943

Later, Noor Inayat

Khan was recruited to join the F (France) Section of the Special Operations

Executive. In early February 1943, she was posted to the Air Ministry,

Directorate of Air Intelligence, seconded to First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY).

She was sent to Wanborough Manor, near Guildford in

Surrey, after which she was ordered to Aylesbury, in Buckinghamshire, for

special training as a wireless operator in occupied territory.

She was the first

woman to be sent over in such a capacity as all the woman agents before she had

been sent as couriers. Having had previous wireless telegraphy (W/T) training,

Noor had the edge over those who were beginning their radio training and was considered

both fast and accurate.

From Aylesbury, Noor

went on to Beaulieu, where the security training was

capped with a practice mission – in the case of wireless operators, to find a

place in a strange city from which they could transmit back to their

instructors without being detected by an agent unknown to them who would be

shadowing them.

The ultimate training

exercise was the mock Gestapo interrogation, intended to give agents a taste of

what might be in store for them if captured and some practice in maintaining

their cover story. Noor's escaping officer found her interrogation "almost

unbearable" and reported that "she seemed terrified … so overwhelmed

she nearly lost her voice" and that afterward, "she was trembling and

quite blanched." [check quotation syntax] Her final report read: "Not

overburdened with brains but has worked hard and shown keenness, apart from

some dislike of the security side of the course. She has an unstable and

temperamental personality, and it is very doubtful whether she is suited to

work in the field." Next to this comment, Maurice Buckmaster, the head of

F Section, had written in the margin, "Nonsense" and that "We

don't want them overburdened with brains."

Noor's superiors held

mixed opinions on her suitability for secret warfare, and her training needed

to be completed due to the need to get trained W/T operators into the field.

Khan's "childlike" qualities, particularly her gentle manner and "lack

of ruse", had greatly worried her instructors at SOE's training schools.

One instructor wrote that "she confesses that she would not like to have

to do anything 'two faced', while another said she was "very feminine in

character, very eager to please, very ready to adapt herself to the mood of the

company; the one of the conversation, capable of strong attachments,

kind-hearted, emotional, imaginative." A further observer said:

"Tends to give far too much information. Came here without the foggiest

idea what she was being trained for." Others later commented that she was

physically unsuited, saying she would not easily disappear into a crowd.

Physically quite

small, Noor received poor athletic reports from her instructors: "Can run

very well but otherwise clumsy. Unsuitable for jumping" "Pretty

scared of weapons but tries hard to get over it." Noor was training as a

W/T operator and getting adequate reports in that field. Her "fist",

or style of tapping the keys, was somewhat heavy, apparently owing to her

fingers being swollen by chilblains, but her speed improved daily. Khan played

the harp and was a natural signaler like many talented musicians.

Further, Vera Atkins

(the intelligence officer for F Section) insisted Noor's commitment was

unquestioned, as another training report had readily confirmed: "She felt

she had come to a dead end in the WAAF and was longing to do something more

active in the prosecution of the war, something that would demand more

sacrifice." So when Suttill's request first came, Vera saw Noor as a

natural choice, and although her final training in field security and encoding

had to be cut short, she judged her ready to go.

Noor's mission would

be an especially dangerous one. So successful had female couriers been that the

decision was made to use them as wireless operators, which was even more

hazardous work, probably the most difficult work. The operator's job was to

maintain a link between the circuit in the field and London, sending and

receiving messages about planned sabotage operations or where arms were needed

for resistance fighters. With such communication, it was almost possible for

any resistance strategy to be coordinated, but the operators were highly

vulnerable to detection, which improved as the war progressed.

Hiding as best they could,

with aerials strung up in attics or disguised as washing lines, they tapped out

Morse on the key of transmitters and would often wait for hours for a reply

saying the messages had been received. If they stayed in the air transmitting

for more than 20 minutes, their signals were likely to be picked up by the

enemy, and detection vans would trace the source of these suspect signals. When

the operator moved location, the bulky transmitter had to be carried, sometimes

concealed in a suitcase or a bundle of firewood. The operator would need a

cover story to explain the transmitter if stopped and searched. In 1943, an

operator's life expectancy was six weeks.

Ultimately, she was betrayed

by a Frenchwoman and was sent to the Dachau concentration camp. There, she went

through hell. She was tortured for information for almost ten months but

refused to reveal anything. She remained loyal to her country till her last

breath. On 13th September 1944, she was shot dead in Dachau alongside three

other SOE agents.

This year, Noor

became the first South Asian woman to be honored with the prestigious Blue

Plaque in Bloomsbury, where she lived. And in 1949, she was posthumously

awarded the George Cross, United Kingdom’s highest civilian award, for all her

efforts.

Noor had been staying

at a country house in Buckinghamshire, where agents had a final chance to

adjust to their new identities and consider their missions before departure.

Noor's conducting officer, a female companion who watched over agents in

training, told Atkins that Noor had descended into gloom and was troubled by

the thought of what she was about to undertake. Then two fellow agents staying

with Noor at the country house had written directly to Vera to say they felt

she should not go. Such an intervention at this stage was most unusual.

Atkins decided to

call Noor back to London to meet and talk. Vilayat remembered trying to stop

his sister from going on her mission exactly at the time of this meeting.

"You see, Nora and I had been brought up with the policy of Gandhi's

nonviolence, and at the outbreak of war, we discussed what we would do",

said Vilayat, who had followed his father and become a Sufi mystic. "She

said, 'Well, I must do something, but I don't want to kill anyone.' So I said,

'Well if we are going to join the war, we have to involve ourselves in the most

dangerous positions, which would mean no killing.' Then, when we eventually

went to England, I volunteered for minesweeping, and she volunteered for SOE,

so I have always felt guilty because of what I said that day."

Noor and Atkins met

at Manetta's, a restaurant in Mayfair. Atkins wanted to confirm that Noor

believed in her ability to succeed. Confidence was the most important thing for

any agent. However, poor Noor's jumping or even her encoding, Atkins thought

those agents who did well were those who knew before they set off that they

could do the job. She intended to let Noor feel she had an opportunity to back

out gracefully should she so wish. Atkins began by asking if she was happy with

what she was doing. Noor looked startled and said: "Yes, of course."

Atkins then told her

about the letter and its contents. Noor was reportedly upset that anybody would

think she was unfit. "You know that if you have doubts, it is not too late

to turn back… If you don't feel you're the type – if you don't want to go for

any reason, you only have to tell me now. I'll arrange everything so that you

have no embarrassment. You will be transferred to another branch of the service

with no adverse mark on your file. We have every respect for the man or woman

who admits frankly to not feeling up to it", Atkins told her, adding:

"For us, there is only one crime: to go out there and let your comrades

down."

Noor insisted that

she wanted to go and was competent for the work. Her only concern, she said,

was her family, and Vera sensed immediately that this was, as she had

suspected, where the problem lay. Noor had found saying goodbye to her widowed

mother the most painful thing she had ever had to do, she said. As Vera had

advised her, she had told her mother only half the truth: she had said she was

going abroad, but to Africa, and she had found maintaining the deception cruel.

Atkins asked if there

was anything she could do to help with family matters. Noor said that, should

she go missing, she would like Atkins to avoid worrying her mother as far as

possible. The normal procedure, as Noor knew, was that when an agent went to the

field, Vera would send periodic "good news" letters to the family,

letting them know the person concerned. If the agent went missing, the family

would be told so. Noor suggested that bad news should be broken to her mother

only if it was beyond doubt that she was dead. Atkins said she would agree to

this arrangement if it were what she wanted. With this assurance, Noor seemed

content and confident once more. Any doubts in Atkins's mind were also now

apparently settled.

Westland Lysander Mk III (SD) was used for special

missions in occupied France during World War II.

Atkins always

accompanied the woman agents to the departure airfields if she possibly could.

Those who were not dropped into France by parachute (as were agents like Andrée

Borrel and Lise de Baissac) were flown in on

Lysanders, a light monitoring transport aircraft designed to land on short and

rough fields. These planes were met by a "reception committee"

consisting of SOE agents and local French helpers. The reception committees

were alerted to the imminent arrival of a plane by a BBC action message inserted

as message personnel; these were broadcast across France every evening, mostly

for ordinary listeners wishing to contact friends or family separated by war.

The messages broadcast for SOE, agreed in advance between HQ and the circuit

organizer, usually by wireless signal, sounded like odd greetings or aphorisms

– "Le hibou n'est pas

un éléphant" (The owl is not an elephant) – but

the reception committee on the ground would know that the message meant a

particular (pre-planned) operation would take place.

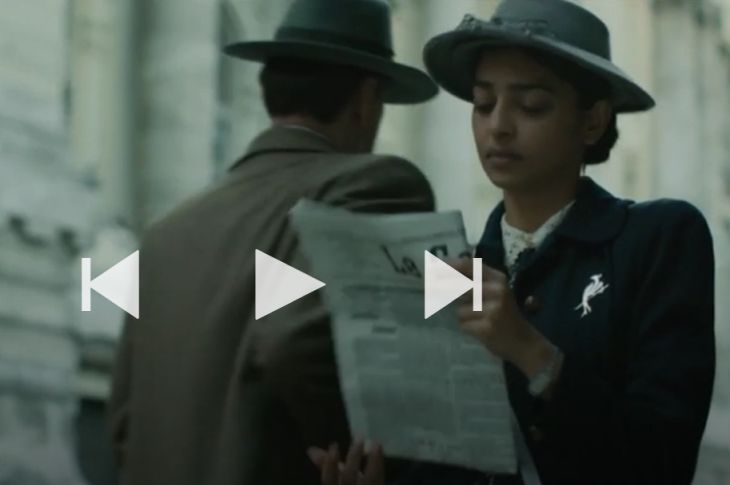

Promoted to Assistant

Section Officer (the WAAF equivalent of RAF pilot officer), Noor was to fly by

Lysander with the June moon to a field near Angers, from where she would make

her way to Paris to link up with the leader of a Prosper sub-circuit named Emile

Garry, or Cinema, an alias chosen because of his uncanny resemblance to the

film star Gary Cooper. Once on the ground, Noor would contact the Prosper

circuit organizer, Francis Suttill, and take on her new persona as a children's

nurse, "Jeanne-Marie Renier", using fake papers in that name. To her

SOE colleagues, however, she would be known simply as "Madeleine".

Regardless of her

perceived shortcomings, Noor's fluent French and her competency in wireless

operation – coupled with a shortage of experienced agents – made her a

desirable candidate for service in Nazi-occupied France. On 16/17 June 1943,

cryptonym 'Madeleine'/W/T operator 'Nurse' and under the cover identity of

Jeanne-Marie Regnier, Assistant Section Officer Noor was flown to landing

ground B/20A 'Indigestion' in Northern France on a night landing double

Lysander operation, code-named Teacher/Nurse/Chaplain/Monk, along with agents

Diana Rowden (code-named Paulette/Chaplain), and Cecily Lefort (code-named

Alice/Teacher). Henri Déricourt met them.

From 24 June 1943,

the 'Prosper' network that Noor had been sent to be a radio operator for began

to be rounded up by the Germans. Noor remained in radio contact with London.

When Buckmaster told her she would be flown home, she would prefer to remain, as

she believed she was the only radio operator remaining in Paris. Buckmaster

agreed to this, though she was told only to receive signals, not to transmit.

Noor Inayat Khan was

betrayed by the Germans, possibly by Renée Garry. Garry was the sister of Émile

Henri Garry, the head agent of the 'Cinema' and 'Phono' circuits, and Inayat

Khan's organizer in the Cinema network (later renamed Phono). Émile Henri Garry

was later arrested and executed at Buchenwald in September 1944.

Renée Garry was

allegedly paid 100,000 francs (some sources state 500 pounds). Her actions have

been attributed at least partially to Garry's suspicion that she had lost the

affection of SOE agent France Antelme to Noor. After

the war, she was tried but escaped conviction by one vote.

On or around 13

October 1943, Noor was arrested and interrogated at the SD Headquarters at 84

Avenue Foch in Paris. During that time, she attempted to escape twice. Hans

Kieffer, the former head of the SD in Paris, testified after the war that she

did not give the Gestapo a single piece of information but lied consistently.

However, other

sources indicate that Noor chatted amiably with an out-of-uniform Alsatian

interrogator and provided personal details that enabled the SD to answer random

checks in the form of questions about her childhood and family.

Inayat Khan's

inscription at the Air Forces Memorial at Runnymede, England, memorializes

those without a known grave. Noor did not talk about her activities under

interrogation, but the SD found her notebooks. Contrary to security

regulations, Noor had copied out all the messages she had sent as an SOE

operative (this may have been due to her misunderstanding what a reference to

filing meant in her orders and also the truncated nature of her security course

due to the need to insert her into France as soon as possible). Although Noor

refused to reveal any secret codes, the Germans gained enough information from

them to continue sending false messages imitating her.

Some claim London

failed to properly investigate anomalies that would have indicated the

transmissions were sent under enemy control, particularly the change in the

'fist' (the style of the operator's Morse transmission). As a WAAF signaller, Noor had been nicknamed "Bang Away

Lulu" because of her distinctively heavy-handed style, which was said to

be a result of chilblains. However, according to M.R.D. Foot, the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) were quite adept at faking

operators' fists. The well-organized and skillful counter-espionage work of the

SD under Hans Josef Kieffer is, in fact, the true reason for the intelligence

failures.

Additionally, Déricourt, F Section's air-landing officer in France,

literally gave SOE's secrets to the SD in Paris. He would later claim to have

been working for the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS, commonly known as MI6),

without the knowledge of SOE, as part of a complex deception plan in the run-up

to D-Day.

As a result, three

more agents sent to France were captured by the Germans at their parachute

landing, including Madeleine Damerment, who was later

executed. Sonya Olschanezky ('Tania'), a locally

recruited SOE agent, had learned of Noor's arrest and sent a message to London

through her fiancé, Jacques Weil, telling Baker Street of her capture and

warning HQ to suspect any transmissions from "Madeleine".

Colonel Maurice

Buckmaster ignored the message as unreliable because he did not know who Olschanezky was. As a result, German transmissions from

Noor's radio continued to be treated as genuine, leading to the unnecessary

deaths of SOE agents, including Olschanezky, who was

executed at Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp on

6 July 1944. When Vera Atkins investigated the deaths of missing SOE agents,

she initially confused Noor with Olschanezky (similar

in appearance), who was unknown to her, believing Noor had been killed at Natzweiler, correcting the record only when she learned of

Noor's fate at Dachau.

On 25 November 1943,

Noor escaped from the SD Headquarters, along with fellow SOE agent John Renshaw

Starr and resistance leader Léon Faye, but was recaptured in the vicinity.

There was an air raid alert as they escaped across the roof. Regulations required

a count of prisoners at such times, and their escape was discovered before they

could escape. After refusing to sign a declaration renouncing future escape

attempts, Noor was taken to Germany on 27 November 1943 "for safe

custody" and imprisoned at Pforzheim in solitary confinement as a

"Nacht und Nebel" ("Night and Fog": condemned to

"Disappearance without Trace") prisoner, in complete secrecy. For ten

months, she was kept there, shackled at her hands and feet.

Noor was classified

as "highly dangerous" and usually shackled in chains. As the prison

director testified after the war, Noor remained uncooperative and continued to

refuse to give any information on her work or her fellow operatives, although

in her despair at the appalling nature of her confinement, other prisoners

could hear her crying at night. However, by scratching messages on the base of

her mess cup, Noor was able to inform another inmate of her identity, giving

the name of Nora Baker and the London address of her mother's house.

Execution

Noor Inayat Khan was

abruptly transferred to the Dachau concentration camp along with her fellow

agents, Yolande Beekman, Madeleine Damerment, and

Eliane Plewman.

A Gestapo man named

Max Wassmer was in charge of prisoner transports at Karlsruhe and accompanied

the women to Dachau. Another Gestapo man named Christian Ott told US

investigators the fate of Noor and her three companions after the war. Ott was

stationed at Karlsruhe and volunteered to accompany the four women to Dachau

because he wanted to visit his family in Stuttgart on the return journey.

Although he was not present at the execution, Ott told investigators what

Wassmer had told him.

The four prisoners

had come from the barrack in the camp, where they had spent the night, into the

yard where the shooting was to take place. Here he [Wassmer] announced the

death sentence to them. Only the Lagerkommandant and

the two SS men were present. The German-speaking Englishwoman (the major)

notified her companion about the death sentence. All four prisoners had grown

pale and wept; the major asked if they could protest against the sentence. The Kommandant declared that nobody could protest against the

sentence. The major then requested to see a priest. The camp Kommandant denied the major's request on the ground that

there was no priest. Now the four prisoners were ordered to kneel with their

heads facing a small mound of earth before they were killed by the two SS men,

one after another by a shot through the back of the neck. The two Englishwomen

held hands during the shooting, and the Frenchwomen did the same. For three of

the prisoners, the first shot caused their deaths, but for the German-speaking

Englishwoman, a second shot needed to be fired because she still showed signs

of life after the first shot was fired. After shooting these prisoners, the Lagerkommandant said to the two SS men that he took a

personal interest in the women's jewelry and should be taken into his office.

This is an unreliable

account because Ott told the investigator that he had asked Wassmer the

following question after he was told what had happened to the women: "But

tell me, what happened," to which Wassmer replied: "So you want to

know how it happened?"

In 1958, an anonymous

Dutch prisoner asserted that Noor was cruelly beaten by an SS officer named

Wilhelm Ruppert before she was shot from behind. Her last word was reported as

"Liberté". Her mother and three siblings survived Noor.

Honors And Awards

Croix de Guerre avec

étoiles vermeil

Memorial bust of

Inayat Khan in Gordon Square Gardens, Bloomsbury, London

Noor Inayat Khan was

posthumously awarded the George Cross in 1949, and she was awarded a French

Croix de Guerre with a silver star (avec étoile de vermeil). Because she was

still considered "missing" in 1946, she could not be awarded a Member

of the Order of the British Empire. Still, her commission as Assistant Section

Officer was gazetted in June (with effect from 5 July

1944), and she was Mentioned in Despatches in October

1946. Noor was the third of three Second World War FANY members to be awarded

the George Cross, Britain's highest award for gallantry in the face of the

enemy.

At the beginning of

2011, a campaign to raise £100,000 to pay for the construction of a bronze bust

of her in central London close to her former home was launched. The unveiling

of the bronze bust by Princess Royal took place on 8 November 2012 in Gordon

Square Gardens, Bloomsbury, London.

Noor was commemorated

on a stamp issued by the Royal Mail on 25 March 2014 in a set of stamps about

"Remarkable Lives". In 2018, a campaign was launched to have Noor

represented on the next version of the £50 note.

1. A significant

source here is Jean Overton Fuller (1915–2009), a friend of Noor and the

Inayat Khan family. Her account of Noor’s life and wartime work was based on

in-depth research, including official documentation and extensive interviews

with Noor’s family, friends, fellow SOE agents, and administrators.

Jean Overton Fuller was also a member of the Theosophical Society based in

Adyar, India.

For updates click hompage here