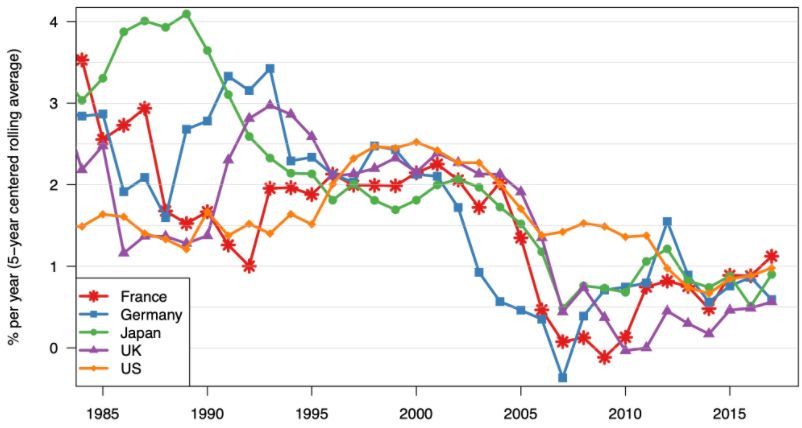

While labor productivity

growth in five advanced economies has seen a downturn,

as creators and workers realize their collective power in the coming

months and years, these movements will grow in number. And as demonstrated

throughout history, many can sometimes significantly outperform

the power of the hierarchical few:

economics and real-time revolution. Also, recently three

economists & a revolution: 2021’s economics Nobel laureates freed the discipline

from limiting theory bonds. Whereby platforms like Facebook and

other media have rewritten the contract between workers and companies.

The pandemic has made

many observers look clueless about the world economy. Few predicted $80 oil,

let alone fleets of container ships waiting outside Californian and Chinese

ports. As covid-19 let rip in 2020, forecasters overestimated how high unemployment

would be by year-end. Today prices are rising faster than expected, and nobody

knows if inflation and wages will spiral upward. Economists often struggle with

too little information to pick the policies that maximize jobs and growth.

The world is on the

brink of a real-time revolution in economics as the quality and timeliness of

information are transformed. Big firms from Amazon to Netflix already use

instant data to monitor grocery deliveries and how many people are glued to

“Squid Game.” The pandemic has led governments and central banks to experiment,

from watching restaurant bookings to tracking card payments. The results are

still rudimentary, but as digital devices, sensors, and fast prices become

ubiquitous, the ability to observe the economy will improve. That holds open

the promise of better public-sector decision-making - as well as the temptation

for governments to meddle.

The desire for better

economic data is hardly new. America’s gnp estimates

date to 1934 and initially came with a 13-month time lag. In the 1950s, a young

Alan Greenspan monitored freight-car traffic to arrive at early estimates of

steel production. Ever since Walmart pioneered supply-chain management in the

1980s, private-sector bosses have seen timely data as a source of competitive

advantage. But the public sector has been slow to reform how it works. The

official figures that economists track - think of gdp or

employment - come with lags of weeks or months and are often revised

dramatically. Productivity takes years to calculate accurately. It is only a

slight exaggeration to say that central banks are flying blind.

Insufficient and late

data can lead to policy errors costing millions of jobs and trillions of

dollars in lost output. The financial crisis would have been less harmful had

the Federal Reserve cut interest rates near zero in December 2007, when America

entered recession. Patchy data about a vast informal economy and rotten banks

have made it harder for India’s policymakers to end their country’s decade of

low growth. The European Central Bank wrongly raised interest rates in 2011

amid a temporary burst of inflation, sending the euro area back into

recession. The Bank of England may be about to make a similar

mistake today.

This week’s comments

by Andrew Bailey, the bank’s governor, led traders to place about 80% odds on a

rate increase on November 4th. While the governor has promised only to be

vigilant, the bank has not disabused bond desks of the notion that a series of rate

rises are imminent. Inflation has risen to over 3% and will probably reach 5%

by spring. But many of the forces pushing it up, such as energy-price

increases, should prove temporary. The bank should disregard inflation when it

is caused by supply disruptions, such as higher commodity prices.

The pandemic has

changed the way governments and central banks conduct business. Without the

time to wait for official surveys to reveal the effects of the virus or

lockdowns, they have experimented, tracking mobile phones, contactless

payments, and real-time use of aircraft engines. Today’s star economists run

well-staffed labs that crunch numbers. Firms such as JPMorgan Chase have opened

up treasure chests of data on bank balances and credit card bills, helping

reveal whether people are spending cash or hoarding it.

These trends will

intensify as technology permeates the economy. A larger share of spending is

shifting online, and transactions are being

processed faster. Real-time payments grew by 41% in 2020, according to

McKinsey. More machines and objects are being fitted with sensors, and Govcoins, or central-bank digital currencies (cbds), might soon provide a goldmine of real-time detail

about how the economy works.

Timely data would cut

the risk of policy cock-ups - it would be easier to judge if a dip in activity

was becoming a slump. And the levers governments can pull will improve, too.

Central bankers reckon it takes 18 months or more for a change in interest rates

to take full effect. But Hong Kong is trying out cash handouts in digital

wallets that expire if they are not spent quickly. cbd might

allow interest rates to fall profoundly negative. Good data during crises could

let support be precisely targeted; imagine loans only for firms with robust

balance sheets but a temporary liquidity problem. Instead of wasteful universal

welfare payments made through social-security bureaucracies, the poor could

enjoy instant income top-ups if they lost their job, paid into digital wallets

without any paperwork.

The real-time

revolution promises to make economic decisions more accurate, transparent, and

rules-based but also brings dangers. New indicators may be misinterpreted, as

are the detailed surveys by statistical agencies. Big firms could hoard data,

giving them an undue advantage. Private firms such as Facebook,

which launched a digital wallet this week, may one day have more

insight into consumer spending than the Fed does.

The most significant danger

is hubris. With a panopticon of the economy, it will be tempting for

politicians and officials to imagine they can see far into the future or mold

society according to their preferences and favor particular groups. This is the

dream of the Chinese Communist Party, which seeks to engage in the form of

digital central planning.

No amount of data can

reliably predict the future. Unfathomably complex, dynamic economies rely not

on Big Brother but on the spontaneous behavior of millions of independent firms

and consumers. Instant economics isn’t about clairvoyance or omniscience. Instead,

its promise is prosaic but transformative: better, timelier, and more rational

decision-making.

For updates click homepage here