The reason why the Hess/Hitler overture to England was ignored by Churchill et al is because they knew

of potential much better deals that included the replacement of

Hitler. With the knowledge of Hitler’s spy chief who was in constant contact

with London since 1938 two attemps where made to

murder Hitler. And by the summer of 1942-if not before, in December 1941, when

the United States entered the War Heinrich Himmler was convinced that Germany

would lose, and begun searching for ways to ingratiate himself with the Western

Allies, using the SS and the Nazi Party security apparatus as bargaining chips.In fact in 1941 British intelligence had been passed

off fake ‘Nazi documents’ to the US President, which he used to persuade

Congress to bring America ever closer to direct engagement. Although it gives

me no pleasure to revisit legends such as Stalin, Hitler, Churchill and

Roosevelt.

Social Science Discovers: Heinrich Himmler's High

Treason Rendezvous at Zhitomir

Convinced since early

1942 that Germany would lose the War, in August 1942 Himmler proceeded to

Zhitomir where he explained the head of the "Sicherheitsdienst"

Schellenberg, how to unseat Hitler in a putsch that would be followed by a secret

deal for a negotiated peace with the Western Allies in exchange for license to

continue Germany's war with the Soviet Union.

|

|

|

|

Schellenberg (far right),

a witness at the Nuremberg war crimes trials, sits with former subordinates

in the Sicherheitsdienst-foreign intelligence-including Wilhelm Hoettl (on his right), who handled Balkan intelligence

for Schellenberg.

|

|

In Germany, Hitler's

reaction to Hess's flight was largely motivated by fear of losing face before

his own people should they discover that their Führer, whilst exhorting them to

fight on in his war of conquest, had actually been secretly involved in

negotiations with certain top Britons to make peace and end the war. Indeed, he

had even offered to at some point to withdraw all German forces from occupied

Western Europe in order to attain a deal.

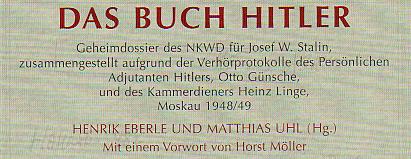

Aus der Akte Nr. 462a im Bestand 5 Verzeichnis 30 im Russischen

Staatsarchiv für Zeitgeschichte, Moskau. (English text

continues underneath)

„Aus Hitlers Umgebung sickerte durch, dass die

Entscheidung, Heß für geistesgestört zu erklären, in Hitlers Besprechung mit

Göring, Ribbentrop und Bormann gefallen war.

Als aus London die Meldung kam, der Duke of

Hamilton bestreite, mit Heß bekannt zu sein, entfuhr es Hitler spontan: »Was

für eine Heuchelei! Jetzt will er ihn nicht einmal kennen!«

Bei den Gesprächen in Hitlers Stab über den Flug von Heß wurde

unter dem Siegel der Verschwiegenheit geäußert, dass dieser ein Memorandum über

die Friedensbedingungen mit England bei sich habe: Heß hätte es aufgesetzt und

Hitler zugestimmt.

Dessen Hauptpunkt sei gewesen, dass England Deutschland freie

Hand gegenüber Sowjetrussland lassen werde, während Deutschland England den

Erhalt seines Kolonialbesitzes und die Vorherrschaft im Mittelmeerraum

garantiere.

Außerdem würde in dem Memorandum herausgestellt, dass ein

Bündnis »der großen Kontinentalmacht Deutschland« mit der »großen Seemacht

England« ihnen die Herrschaft über die ganze Welt sichern werde. Zudem wurde

bekannt, dass Heß seit dem Februar 1941 intensiv- mit der Ausarbeitung der

politischen und wirtschaftlichen Vorschläge befasst gewesen sei, die die

Grundlage der Verhandlungen mit den Engländern bilden sollten. Daran waren

weiter beteiligt: der Chef der Auslandsorganisation der nationalsozialistischen

Partei Bohle, der Ministerialrat im Reichswirtschaftsministerium Jagwitz, General Karl Haushofer und Heß' Bruder Alfred, Bohles Stellvertreter. P. 145 from:

The extraordinary

truth is that, for sixty years, a potentially devastating political secret has

been covered up by subterfuge. This secret was related to British fears in 1940

and 1941 that the country might go down to crushing defeat, and to how Britain's

top political minds determined that Britain would survive. The means they used

to accomplish this were ingenious and extremely subtle, but also unscrupulous.

They were the acts of desperate men, faced with the options of either

catastrophic defeat or national survival.

By its very nature,

what was done became a secret that could never be revealed. The decision to

promulgate the legend of the standalone nation - that Britain had survived

through pure military endeavour and luck - meant that

disclosure during the dangerous years of the Cold War would have resulted in

the shattering of Britain's international credibility, and the ruin of many

political careers.

Yet it could also be

said that there was another, more noble, purpose to keeping this secret for all

time. The impression has always been maintained that the Nazi leaders were a

bizarre range of individuals, devoid of compassion for humanity - and, in many

cases, evil personified. If, however, the truth should turn out to be that some

of these men had considerable political acumen, but that the inexorable spread

of the Second World War resulted largely from their inability to control the

situation, the distinction between pernicious men of evil intent, and

politicians unable to control the flames of war they had themselves lit,

becomes less clear-cut.

As early as January

1936, shortly after succeeding to the throne, King Edward VIII had sent word to

Hitler via a German kinsman, Carl Eduard, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, to say

that he believed an alliance between Great Britain and Germany was politically

necessary and that it could even lead to a military pact including France. It

was therefore his wish, King Edward said, to speak personally to the Reich

Chancellor as soon as possible, either in Britain or Germany.

Hitler thus saw

Edward's abdication as a victory for those forces in Britain that were hostile

to Germany. Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German ambassador in London, confirmed

Hitler's view that `the King had been deposed as the result of a

“Jewish-Masonic conspiracy” (the traditional view of the Nazi’s overall,

see: Hitler’s Secret Protocols.)

After Edward's

abdication One of the first big projects the Windsors undertook in 1937 was a

trip to National Socialist Germany. Now would come the meeting that Edward had

wished for: as Duke of Windsor he visited Adolf Hitler, Chancellor of the

German Reich, albeit not in Berlin, but at his private residence, the Berghof,

near Berchtesgaden in Bavaria.

There have never been

any British disclosures of the details of what the Duke of Windsor was

negotiating with Hitler and later the German government when he was working for

the British Foreign Office in Portugal. The only clues to have surfaced allude

to a seven-point plan, which was of sufficient importance for Hess secretly to

meet the Duke in the privacy of the Sacramento a Lapa home of the German

Ambassador to Portugal, Hoyningen-Huene, on Sunday,

28 July 1940, for a series of secret meetings. Unfortunately, the Duke was

spotted by expatriates living nearby.

And on 1 August the

Duke, under increasing pressure from the London, departed for the faraway

Bahamas. His endeavours to negotiate a peaceable

accord proceeded not one jot further, for the British government refused to

countenance any more interference from the man who had caused such

constitutional turmoil less than four years before. Also, unbeknownst to the

Duke of Windsor, peace with Germany was the last thing on Winston Churchill's

mind.

The next (some say it

was the fourth) peace offer would emanate directly from Hitler himself, and it

would be so secret that the Führer told no one in Germany about it at all, not

in the diplomatic service, the government, or the party; not even his inner

circle.

This latest attempt

to open peace discussions caused considerable consternation in Whitehall. The

very few men in the British Foreign Office who knew about it feared that the

more impressive these peaceable attempts became, the greater the likelihood that

they might dent Lord Halifax's determination to stand by Churchill and his `no

surrender' policy, and the resolve of those in the government who might be

tempted to accept a quick fix today, and worry about a Europe dominated by Nazi

Germany tomorrow. There was concern that the British government might split

between those determined to defeat Germany, and those who might vote against

Churchill in the House of Commons for peace, to save Britain from any further

suffering. This new initiative came at the height of the Blitz, those crucial

weeks of the Battle for Britain, which made the situation all the more

worrying.

Hitler's offer on

this occasion indicated that he was now approaching peace from a geopolitical,

rather than military, point of view, revealing the continuing influence of his

long discussions with Karl Haushofer in the 1920s and thirties. It also perhaps

indicates that the intellect and the foreign affairs interests of Rudolf Hess

lay behind the offer now being proposed to the British Ambassador in Stockholm,

Victor Mallet, via Swedish High Court Justice Dr Ekeberg, duly reported back to

London that:

Hitler's peace

terms as follows:

1 The Empire remains

with all the colonies and mandates.

2 The continental supremacy of Germany will not be called into question.

3 All questions concerning the Mediterranean and the French, Belgian and Dutch

colonies are open to discussion.

4 Poland. There must be `a Polish State'.

5 Czechoslovakia must belong to Germany.

But, that Hitler

wished to re-establish the sovereignty of all the occupied countries 'auf die dauer' [i.e. later on, on a permanent basis]. In the

economic sphere, however, the occupied countries must be part of the European

continent, but with complete political liberty (Doc. No. FO 371/24408 - Public

Records Office, Kew, England).

Seen in context, by

the summer of 1940 Germany had conquered Poland, Norway, Denmark, Luxembourg,

Holland, Belgium and France. The British Army had been defeated and only just

escaped from Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain was raging in the skies over London

and the Home Counties, and Britain's cities were suffering a ferocious blitz

both night and day. Vansittart's letter to Lord Halifax makes it clear

that Whitehall and especially Churchill, had viewed Germany - and not

particularly Nazism - as a threat ever since WWI (Doc. No. FO 837/593 - Public

Records Office, Kew). This emanated from the German policy of 'Drang nach Osten', which came with the fall of the Ottoman

Empire, when General von Moltke and later the Kaiser became convinced that

Germany could fill the resultant power-vacuum.

For updates

click homepage here