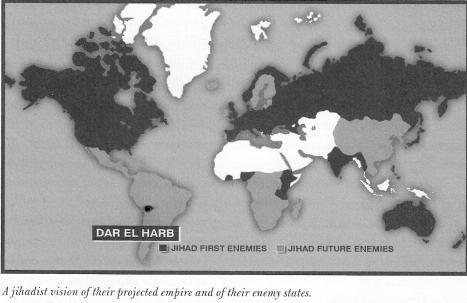

What few people in

Europe and the USA seem to be aware of are the actual future war projections by

Islamists and Jihadists, see map underneath. A first question to ask here then

is of course also, what will be their future alliances?

In fact one can see

hints of possible future alliances forming among the Islamists/ jihadists by

looking at the complex alliances of the past. After most of the Arab Middle

East fell under European rule as a result of the Ottoman collapse, the Islamic

fundamentalist movement began to look worldwide to find potential allies

against the Franco-British occupation. The Muslim Brotherhood, the Wahabis, and

even the Pan Arab nationalists viewed the rise of radical nationalism in Europe

as a historic opportunity. The convergence between the two currents across the

Mediterranean, although ultimately fruitless, had grounds in pure geopolitics.

From various quarters of the region, including Cairo, Jerusalem, and Baghdad,

leading figures of the transnational Salafi movement opted for a rapprochement

with the emerging Nazi and fascist regimes in Berlin and Rome. The jihadi

movement operated through the ancient geopolitical logic that the enemy of

one's enemy could be a potential ally. Thus arose the Islamist-Jihadic-Nazi-fascist

axis.

Ideologically, the

equation had no philosophical pillars. The National Socialists of Germany

promoted German racial superiority. Arabs and other Mideastern Semites were at

the bottom of the ladder, lower even than the Slavs and Turks. The racist

ideology of nazism was thus inherently incompatible

and could not be adopted by the Islamic fundamentalists because of their own

ethnicities. In a global society ruled by the Third Reich, by "Aryan

standards" Arab Muslims would be one level above the Jews. In Nazi thinking,

a universal Germanic empire would not be co ruled with southern Mediterranean

"races" who were considered inferior, and a longterm

joint venture between Hitler and potential allies in the Arab world was

impossible.

For the Italian

fascists, with their idea of the Roman "Mare nostra," the

Mediterranean could accommodate neither Arab nationalism nor Islamic fun damentalism. On the Arab Islamic end, cooperation also was

not possible, for the simple reason that the agenda of the jihadic

forces called for the removal of all infidel presence from Arab and Muslim

lands. Mussolini had been engaged in the opposite activity, having invaded

Ethiopia and dreamed of a new Italian empire. Italians would have had to

evacuate Libya and the Germans (if successful) would have to surrender British

and French colonies and mandates back to a caliphate. Further down the

doctrinal and geopolitical road, the supporters of the Islamic conquest-or el Fatah-were dedicated to resuming it beyond the borders

of the old Ottoman empire. Thus, after the Axis victory over the Allies,

another round of jihad would take place against the German Nazis and the

Italian fascists. An ultimate confrontation along the lines of the clash of

civilizations, regardless of who was on the other side, was ineluctable. The

logic ofjihad is not flexible, but can absorb a time

factor. In sum, Salafi political thought throughout the late 1930s and at the

onset of World War II sought an alliance with the German-Italian kuffar against

the Franco-British kuffar, even though, on doctrinal grounds, a universal

project with Nazis and facsists was not possible. But

the calculation was rational, even within the Islamic fundamentalist ideology,

insofar as the ultimate goal for the jihadists was to reemerge as a force

capable of restoring the caliphate. What superseded in the jihadist agenda was

the return of the global institution inside the Muslim lands. Reestablishing

the caliphate was equated with satisfYing Allah, and

therefore benefited from divine support. Striking deals with some kuffar

against other kuffar was in line with Salafi thinking; they often referred to

examples from the preceding founders and even from previous caliphs. According

to these references, in the early days of Islam, Prophet Mohammed had concluded

agreements with non-Muslims as a way to concentrate on other enemies (also

non-Muslims). Also, Abbasid Caliph Harun el Rashid

signed treaties with the "infidel" emperor Charlemagne to balance

power with the other "infidel" emperors of Constantinople. Islamic

history abounds with these examples, and the twentieth-century Salafis used all

of them to show theologicallegitimacy for their

strategic choices.

But in view of the

situation prevailing in the Middle East since the 1920s, the jihadic rationale in the 1930s was first and foremost

geopolitical. Hitler's and Mussolini's armies were the rivals of French and

British powers. Most Muslim lands were occupied by the latter colonial powers.

The resources of industrial Germany and agricultural Italy were being massed

against the interests of the Allies, and therefore were beneficial for jihad

and fatah. The Ottoman Empire adopted a similar

strategy at the beginning of the century. Istanbul perceived Britain, France,

and Russia as its greater threats; hence the Turks sided with Berlin and Vienna

against London and Paris, forming the Central Powers alliance. Although the

move was clearly based on geopolitical equations, it was perceived by the

post-Ottoman Islamic fundamentalists as a deliberate choice by the ruler ofIslam-the sultan-to use the forces of two kuffar powers

against even more threatening infidel powers. But after the abolition of the

caliphate and the sultanate in 1923 at the hands of Kemal Mustafa Ataturk, the

central decision-making authority in the Muslim world vanished. The Wahabis and

Muslim Brotherhood took it upon themselves to embody the international decisions

of the caliphate. They felt, like all Salafis, that the jihadic

strategic decisions were to be decided and developed by them until the return

of the khilafa (succession). Hence, as the collision

between the Berlin-Rome axis with the London-Paris axis was projected,

Islamists (but also many Pan Arabists) saw the strategic convergence of

interest (Taqatuh al Masalih).

Germany had developed enough military power to confront France and England in

Europe, potentially weakening them in the Middle East and North Africa. At the

same time, fascist Italy would disrupt British and French maritime power in the

Mediterranean. Although all these considerations favored siding with the Axis

against the Allies, perhaps the most inflammatory argument in favor of an

alliance with the Nazis was the Jewish question.

The Jewish question

in the Salafi doctrine is threefold: theological, historical, and

geopolitical. It is obviously a major feature of the current jihadist-J ewish conflict (to be discussed in due course), but

already in the 1930s both Arab nationalists and Islamic fundamentalists had

perceived the growth of Jewish settlement in British-mandated Palestine as a

"dagger planted in the midst of the umma (nation)." Arabs in

Palestine had launched an insurrection against British rule and aimed at

uprooting the developing Yishuv (the term for the localJewish

community prior to 1947). The Salafi-jihadic movement

intended to reverse the process of infidel settlement on that very strategic

area of Muslim land known to the West as the Holy Land. Their vision of events

in Palestine was as follows: The British invaded the Arab Middle East,

including Palestine, in 1919. The Jews had concluded a treaty with the British

in 1917, embodied in the Balfour declaration. British infidels had since

allowed Jewish infidels to immigrate onto the Muslim land of Palestine. Hence,

by the same logic, the growth of the Jewish community in that area was not the

result of natural demography under Muslim sovereignty but a consequence of a

strategy designed jointly by two kuffar powers: the British and the Jews. The

conclusion to this jihadic logic was simple:

The Islamic

fundamentalists had to shop for an ally with an ideology that sought to destroy

the Jewish community universally and that had enough military strength and

intent to clash with the other infidel power protecting the Jewish entity in

Palestine. In the 1930s, such an ally was not difficult to identify: Nazi

Germany. Thus, the jihadist solution to the mounting threat of Zionism in

Palestine was to develop an alliance across the Mediterranean with Hitler's

regime. A Nazi higher technology that would confront Jewish technological

superiority and its British protection in Palestine, coupled with the Nazi's

intention to destroy Jewish communities wherever they encountered them and

their imminent confrontation with and likely defeat of the British empire, made

the Nazi option too attractive in realistic political terms to be analyzed in

strictly theological terms (under which, of course, it would have to be

rejected). While Nazi infidels were ultimately anathema to jihadists, the

alliance answered all their practical needs at the moment.

By the end of the

1930s, Islamic fundamentalist networks, often under the auspices of traditional

leadership and sometimes within the wider context of radical Arab nationalists,

sought rapprochement and alliance with Berlin. In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood

hoped a war with the Axis would bring in the German-Italian forces from Libya

across the border to seize the Suez Canal, ejecting the British from the

region. In Syria and Lebanon, fundamentalist leaders envisioned that a defeat

at the hands of the Germans would evacuate the French from the area. In

Palestine and Iraq, revolts were brewing, waiting to be triggered by the

advance of Nazi forces across Europe.

As the Wehrmacht

marched into Czechoslovakia and Poland, and as the Luftwaffe bombarded the

British Isles after the invasion of France, the Islamic fundamentalist and Pan

Arabist movements of the Middle East rose up at different times, in different

areas, and in different circumstances. In Cairo, according to Anwar Sadat's

memoirs, the Muslim Brotherhood and a number of officers in the military were

preparing to revolt had Bernard Montgomery's 8th Army not been able to stop

Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps. The plan was to inflame Egypt from the inside and

explode an intifada along the valley of the Nile all the way to Ethiopia. In

Palestine, the clearest pro-Nazi move was embodied by the mufti of Jerusalem,

al Husseini.

Descending from a

prominent Qudsi (Jerusalemite) family, which claimed its own descent from the

Prophet, the Husseini were the most visible leaders of the city and of tlle Arab population. But the religious cleric H'!ij Ali al Amin al Husseini jumped from anti-British

colonialism to radical anti-Semitism, becoming Hitler's closest ally in the

Arab-Muslim world. Traveling to Berlin, Mufti Husseini met with the Fuhrer,

established an alliance, and projected himself not only as the Arab leader of

Palestine but as the Third Reich's leading Muslim ally. The Nazi strategists

wanted to see him play a role beyond Palestine; with a special program in

Arabic broadcasting on Radio Berlin, the pro-German cleric mobilized Muslims in

the Balkans against the Serbs and called on Muslim soldiers serving with the

Allies to desert or rise up. Husseini was the highest hope Berlin had for an

offensive south and east of the Mediterranean behind enemy lines.

In Iraq, Mohammed

Rashid al Kailani led a military uprising against British rule in 1941 centered

in what is today the Sunni triangle. In Syria and the Muslim areas of Leba~n, similar groups readied themselves for an eventual

German landing as Nazi forces reached the Greek island of Rhodes. Had the Axis

forces been successful at El Alamein, jihadic

insurgencies would have met up with them in Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and Iraq.

But the British were fast on all fronts:

They eliminated

Kailani's militias in Iraq and invaded Lebanon and Syria with de Gaulle's

French forces to remove the Vichy France representatives. More important, they

destroyed Rommel's Panzers in the Egyptian desert and in 1942 went on the

offensive in Libya, rolling back the Axis and severing the strategic bridge

between Nazism and jihadism. The attempt to defeat the infidel allies using the

fascist infidels was over by 1943; with the fall of Berlin two years later, a

new era started and the forces ofjihad had to

consider new strategies.

World War II was a

major subject of contemplation for the Sunni Wahabi and Muslim Brotherhood and,

later, for the Shi'a Khumeinists. Throughout the

decades, jihadi intellectuals would rethink their strategies based on what

their contemporaries had witnessed and the accounts by historians. In the years

after September 11, 2001, bold extrapolations would be made public by Islamist

thinkers. On al Jazeera TV, leading Ikhwan scholar Sheikh Yussef al Qardawi often cited World War II as a "war to learn

from" and repetitively went over its imthula, or

lessons. Similar conclusions were found on the web, particularly on al Muhajirun, al Khilafa, and al

Ansar.

Al Qardawi spoke of the huge military machinery that

"consumed millions of humans and an incredible amount of material within

the world of kujJar." He drew the viewers'

attention to the fact that the infidels had destroyed each other's powers in an

incredible way in the twentieth century, particularly during World War II.

Asked about the wisdom of his predecessors-meaning the jihadic

forces of the 1930s and 1940s-having sided with the Axis, he argued that

Muslims should perform their wajib (duty) and Allah

would decide the case. The Islamists focused on the fact that the West may well

possess huge military power and resources, but Allah has his own way to destroy

it. Some Salafi analysts reminded their audience of the mere size of the

infidel global force at the eve of the war. 'Just imagine," said a cleric

in a chat room:

How gigantic was the

combination of all kufr powers in 1939. Just add the military strength of Great

Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, America, let alone Japan. By our aqida (doctrine ) they are all Kuffar. Had they united

against Muslims in the 1940s, we wouldn't have had any chance. We were occupied,

divided, weak, uneducated, and deprived of military power. But Allah subhanahu [religious praise] unleashed them against each

other. They destroyed their military machines against each other in Europe,

Russia, and the Pacific. Every battle they fought was a battle where the

infidels were being destroyed, whatever was the winning side. That war [World

War IIJ was preparing the path for Jihad. It helped us weaken them, then

remove many of their armies from our midst. (Paltalk.com in the

"al-ansar" discussion room, September 23, 2004.)

The philosophical

conclusion is that jihadism does not have to fight all wars to defeat all

enemies. The injunction to the mujahidin is to sacrifice all they can,

including themselves when needed. Their contribution is part of a greater plan.

A Salafi commentator reminded his audience of the early stages of the latah:

"Remember when

our ancestors left Arabia in the first century [seventh A.D./e.E.]. The two superpowers of the time were the Persians

and the Byzantines. They have been at each other's throats for hundreds of

years.” (Paltalk.com in the "ansar al sunna wal Jihad" discussion room, January 20, 2005.)

When the Muslim

armies moved forward, he said the kuffars were weak

and exhausted. Islamists have explained World War II in Europe as a sign by

Allah, signaling the impending decline of the infidels after centuries of

military and economic rise. Before the war, most of the Muslim world was under

colonial infidel occupation. In the years after the war, one land after another

was freed from the British, French, Italians, Dutch, and Portuguese. Hundreds

of millions of Muslims obtained independence from foreign occupiers. This was

seen as stage one of a Muslim "reconquista"-first

of the traditional Muslim lands of the caliphate and later of the dar el harb.

By attempting to ally

themselves with the Nazis and fascists in midcentury, modern Islamists sent

this message: Their strategies for jihad and latah supercede

human rights, democracy, and peace. They were able to hold their noses and

countenance an alliance with the Nazis. To them, jihad and ultimately latah are

all there is in international relations. Their alliances with the

antidemocratic forces were not a "balancing act"; there simply was

not anything else on the other side of the scale. Many westerners still

believe that there is some sort of restraint on what the jihadists will do and

what their ambitions are. But theoretically there is no limit to the latah

until the dar el harb ceases to exist, and there are no limits on the

tactics to be used against the infidels.

The trigger of bin

Laden's war against America was-as he often charged-the deployment of American

forces on Muslim lands, and particularly in 1990 in Saudi Arabia, which he

labeled as holy land. Interestingly enough, the actual area forbidden to

non-Muslims is only the rectangle of the Hijaz area, covering Mecca and Medina.

Non-Muslims, including Americans and others, in fact have been present on the

peninsula for decades in great numbers. The British maintained forces in Oman

for ages. But in the Salafi vision of the world, the insult is more about

infidel forces crushing an Arab Muslim force: the Iraqi army. Salafi chats and

websites blamed both Saddam and the Saudis for allowing the Americans to crush

one of the largest and most powerful armed forces in the Arab world. This

ideological vision of international relations is at the root of the Salafi

anger that triggered attacks against the United States.6 Strangely enough, the

Wahabis, the state Salafists, have made the case for not engaging the Americans

as long as they are (or were) supporting Muslim causes, such as defending the

kingdom during the Gulf War and defeating the "Christian" Serbs in

the 1990s. On both accounts the radical Salafis responded that "America

is an infidel power that cannot be trusted." In the jihadi view, Americans

came to help the royal family against Saddam and control oil. And in Bosnia,

they allowed the Serbs to massacre the Muslims first, before they came to their

rescue. There was no argument to convince Osama and his men that America was

not the enemy. It was an ideological decision that transformed the ally of the

past on the plateau of Afghanistan into the next target.

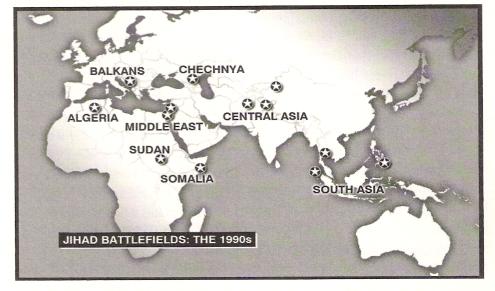

In fact beginning in

1990, Salafi violence erupted in Algeria, Kashmir, Chechnya, Israel, and

elsewhere. In each of these battlefields, local conflicts were different:

political, ethnic,

religious. But, in addition, they were all fueled by one international brand

of ideology: Wahabism and Ikhwan doctrine. The Salafists moved inside these

conflicts and made them into Islamist instead of nationalist ones. For example,

Hezbollah in Lebanon asserted itself among Shiites (as opposed to Sunni

Salafis) and transformed the secular struggle against Israel into a fundamentalist

one. In a sense, these localjihads married the

nationalist conflicts but drove them in one global direction, jihadism,

connecting them to the mother ship of al Qaeda.

As local fires

erupted in several countries, the central force ofjihad,

particularly after the Khartoum gathering in 1992, targeted the United States

head-on, both overseas and at home. By this point al Qaeda was in charge of the

world conflict with America. The "princes" (or emirs) were assigned

the various battlefields, but the "Lord" assumed the task of

destroying the "greater Satan," America.

The first wave

started in 1993 on two axes: One was in Somalia, where jihadists met U.S.

Marines in Mogadishu in bloodshed. The United States withdrew. The same year,

the blind sheikh Abdul Rahman and Ramzi Yusuf conspired to blow up the Twin

Towers in New York. Washington sent in the FBI and treated it as a criminal

case, not as a war on terror. This was another form of withdrawal, and bin

Laden and his brigades got the message. The test was clear: The United States

will not fight the jihadists as a global threat. Something inside America was

"paralyzing" it from even consideringjihad

a threat.

Ironically, the first

ones to understand the message were the jihad terrorists. The events of 1993

were a benchmark in the decision that led to September 11 years later. Bin

Laden said later that the successful suicide attacks by Hezbollah against the

Marines in 1983 convinced him that the United States would not retaliate

against terror. The jihadists tested the United States twice ten years later,

and twice they found the path open.

In 1994, a bomb

destroyed a U.S. facility of Khubar in Saudi Arabia,

killing American military personnel. The "tower" was blown up by

jihadists, but the investigation was not able to determine which group. The

Saudis did not crack down on their radicals and the U.S. administration

absorbed the strike. This was a third test, well appreciated by the jihadists.

Meanwhile, three "wars" erupted worldwide with Salafists either

leading or participating. In Algeria, the fundamentalists have been involved in

tens of thousands of murders against secular, mostly Muslim civilians. The

Algerian regime was responding harshly too. But the United States and France

did not focus on Salafi ideology and organizations. This was a fourth test that

America and the West failed. In Chechnya, the Russians were fighting with the

separatists, whom the Wahabis infiltrated. Some among them would become part of

al Qaeda. Washington addressed veiled criticism to Moscow but kept silent on

the jihadist infiltration of the Chechens. This was the fifth test.

By the early 1990s,

the Bosnian conflict had exploded with its bloody ethnic cleansing. The United

States was first to call for intervention, while the Europeans hesitated.

Washington stood by the besieged Muslims against Serbs and Croats and mounted a

military expedition to help them maintain their government. The jihadists formed

a brigade and fought the Serbs fiercely, expending efforts to recruit elements

for a local jihad-and eventually ship them to other battlefields. Not only did

the United States tolerate the jihadists on the ground, but it even allowed

Wahabi fundraisers in America to support their networks in the Balkans; that

was the sixth test.

In 1996 the Taliban,

one of the most radical Islamist militias on Earth, took over in Kabul. The old

anti-Soviet Afghan allies were pushed all the way north to a precarious

position. The ideology of the Taliban did not seem to impress or worry the

foreign policy decision makers in Washington. The group's ruthless treatment

of women, minorities, and other religious groups went unchecked. Its hosting of

Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda was not dealt with. Worse, businessmen were

interested in contracts under the new "stable" regime, and some

American scholars were impressed with the Taliban's "achievements."

This was the seventh instance of American failure to take any significant stand

against the jihadists anywhere on any issue. It became almost certain that some

"power" inside the United States was moding

America's response and blurring its vision. That year, 1996, bin Laden issued

his first international fatwa against the infidels.

(http://www.defenddemocracy.org/research_topics/ research_topics_show.htm?doc_id=

18567 3 &attrib_id= 7 580.)

Encouraged by the

passivity of the U.S. executive branch toward the escalating jihadi assault

worldwide and against American targets and interests, the "central

computer" launched the second wave. This one was explicit, direct, and

daring, targeting the infidel's diplomatic and military hardware.

On February 22, 1998,

Osama bin Laden appeared on television for about twenty-seven minutes and

issued a full-fledged declaration of war against the kuf

far, America, the crusaders, and the Jews. The text was impeccable, with all

the needed religious references to validate a legitimate jihad. The declaration

was based on a fatwa signed by a number of Salafi clerics. (See The 9/11

Commission Report, op. cit.: "A Declaration of War," p. 47, and

"Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States," p.

59.)

It was the most

comprehensive Sunni Islamist edict of total war with the United States, and it

was met with total dismissal by Washington. It evoked a few lines in the New

York Times, no significant analysis on National Public Radio, and no debating

on C-SPAN. The Middle East Studies Association had no panels on it, and the

leading experts who advised the government downplayed it. During the 9/11

Commission hearings, U.S. officials said they noted it and that plans were

designed to deal with it. As one commissioner asked, "This was a

declaration of war. Why did not the President or anyone declare war or take it

to Congress?"

Here was the leader

of international jihad serving the United States and the infidels with a formal

declaration of war grounded in ideological texts with religious references:

Why did no one answer him? "Expert advice" within the Beltway ruled

against it. Obviously, the Wahabis on the inside did not want to awaken the

sleepy nation. If the U.S. government were to question the basis of Osama's

jihad it would soon recognize the presence of an "internaljihad."

For this reason, the debate about the declaration had to be suppressed and with

it the warning about its upcoming threat. AI Qaeda must have been stunned. They

openly declare war on the infidels, and rather than responding, the Americans

are busy addressing political scandals instead. Osama must have thought:

"Well, that's what the Byzantines did, when the sultan got to their walls

centuries ago. They weren't mobilizing against the fatah,

they were busy arguing about the sex of angels. This must be another sign from

Allah that America is ripe. Let's hit them directly."

And indeed, in August

1998, Osama hit hard: two U.S. embassies, hundreds of victims, and massive

humiliation. The retaliation? A missile was launched on a pharmaceutical plant

in Sudan. Bin Laden had already left the country two years before. A wave of

tomahawk missiles dug up the dirt in Afghanistan. Right place, wrong policy.

Al Qaeda was indeed based in Afghanistan at the time, openly protected by the

Taliban. According to counterterrorism officials and military experts, a plan

was prepared to produce a regime change in Kabul. But again, the "holy

whisper" in the U.S. capital advised against intervention. "It will

create complications in international relations and will have a negative

impact in the Muslim world” Yet the following year, an all-out campaign by al

Qaeda destroyed the Serbian army in Kosovo and led to a regime change in

Serbia. There were no complications in international relations in that case.

The nonresponse of the United States after a declaration of war and a massive

attack against American diplomatic installations was not a mere signal anymore,

it was an invitation to attack America.

In 1999, a plot was

under way to blow up several targets worldwide. Reports circulated about an

earlier plot in 1995 to down several airliners. Intense jihadi activity was

going on; propaganda was spreading around the world. But in the United States,

the elite dismissed any accusation against the Islamists. Worse, the inside

jihadists had initiated a defamation campaign against the very few who were

trying to warn the public and government. America was driven to the

slaughterhouse, politically blindfolded, and intellectually drugged. The

fine-tuning between the outside ninjas and the inside cells was peaking. In

2000, al Qaeda crossed the line to test the U.S. military itself. A fishing

boat blew up, damaging the USS Cole in Yemen. Back in Afghanistan, bin Laden

analyzed the reactions. He did not have much work to do; there was no D.S.

reaction. The anti-American forces worldwide escalated their propaganda

campaign. One cycle led to another, as the jihadists were emboldened on all

battlefields. In Lebanon, Hezbollah overran the South Lebanon Army security

zone after the Israelis abandoned the area in May 2000. In September of that

year, Hamas and Islamic jihad escalated their suicide attacks. And as Americans

were embroiled in counting the Florida votes after the disputed 2000 election,

al Qaeda was scouting the East Coast of the United States. The path to

Manhattan and Washington was wide open.

Since 2001, world

leaders and international public opinion has concluded that the jihadists have

no international law and relations. The Salafi ideological teachings do not

recognize the United Nations, the principles of international law as we know

it, other treaties, conventions, and codes, unless under their doctrinal norms.

In contrast with the communists, who ideologically rejected the capitalist

world but nevertheless recognized international laws and treaties (even though

they often breached them), the jihadists simply do not recognize any system the

international community has reached since the Peace of Westphalia; no

conception of sovereignty, human rights, humanitarian rights, the Geneva

Convention, or even Red Cross agreements. This may seem hard to believe,

especially if you absorb the analysis of the apologists, particularly the Wahabi

lobbies. (See Robert Baer, Sleeping with the Devil: How Washington Sold Our

Soul for Saudi Crude, 2003: "The Honeymoon," p. 91.)

But the easiest way

to learn about it is to read the jihadist literature, study their principles of

action, and listen to their spokespersons and activists. They all confirm with

clarity that the League of Nations, United Nations, Universal Declaration of

Human Rights, democracy, secularism, freedom of religions, freedom of speech

(when not applied in their interest) are to them all "products of the

infidels." Hence, there are no boundaries to jihadist actions. Therefore,

the understanding of their strategies and future plans cannot be predicted

based on expectations of the international community and accepted norms. With

this in mind, we can begin to understand the objectives of September 11 and the

shadow of future jihads.

Of course, the

jihadists, including bin Laden's al Qaeda and the myriad of other radical

Islamist warriors, have a system of reference for their actions. Their clerics

and "legislators" have an entire system oflaws

and regulations, including war codes and traditions (see the 6e pillar of Islam

described earlier in this article series). They, the Islamic fundamentalists,

claim it is the "true Islamic code"; Muslim reformers negate this

claim. This debate existed in the past, continues to exist, and will be much

wider in the future. But the bottom line is that the jihad terror networks

abide by their own vision of international relations: It is the web of

relationship between dar el

harb and dar el Islam. The latter must defeat the former; the rest is

details. But even in the details there are nuances, differences, and multiple subdoctrines. For example, a former member of the Muslim

Brotherhood, Sayid Qutb of Egypt, developed his own vision of warfare and jihad

against the infidels.4 He centered his doctrine almost entirely on constant

violence again the "enemies of religion" until they submit. He did

not spare Muslims of Shiite background or Sunnis of non-Salafi background. Qutb

may be one of the most radical fathers of modernjihadism,

a logical inspiration to al Qaeda, Zarqawi, and future extremists.

When mounting

operations in the 1990s, Osama bin Laden and his men had no limits with regard

to international relations and did not take world opinion into consideration.

In contrast, the state Wahabis were very concerned about al Qaeda's tactics,

fearing they would destroy the credibility of Islamic fundamentalism worldwide.

In the United States and to a certain degree in Europe and elsewhere in the

West, the oil-financed apologists had the choice between condemning the

jihadists and covering up for them. One of their major mistakes was to attack

the target-the United States-instead ofthejihadists.

In fact, the apologists were forced by their ties to the Wahabis to cover up

for the political objectives of the terrorists, and for a simple reason: in the

long term, both the Wahabis and the terrorists have the same objectives. If the

terrorists are exposed, so too will their ideology be exposed. If that happens,

the long-term objectives of the lobbies that are working within the law

internationally and in the United States will be exposed; and just as much as

al Qaeda, the lobbies too believe that the dar el Islam is destined, and in fact, obligated to ovewhelm and absorb the dar el harb. As mentioned in an

earlier chapter, the various parties who debated the September 11 attacks on al

Jazeera television were not arguing about whether the attacks were wrong or

right; they were arguing about whether they'd been mounted at the right time.

It remains to explain

why the American public and the international community were not informed or

educated as to the jihadists' real attitude regarding world affairs. Why were

the terrorists presented either positively, as "freedom fighters," or

negatively, as "mere gangs," and never realistically, as an

ideological network with a worldview rooted in hundreds of years of tradition

and example (the caliphate), and now aiming at the destruction of the world international

structure and the United States in particular? The fundamentalists realized

that they were operating in an ideal context: Not only were they not on their

enemies' radar, but someone on the "inside" was blurring the enemy's

understanding of the networks.

To know what was in

the mind of Osama when he engineered what he called "blessed strikes"

(al-darabat al mubaraka),

short of interviewing him directly or reading his memoirs, requires us to

connect the dots from a combination of statements, over a span of a decade at

least, and to read that material with the deepest possible knowledge of the

movement that produced bin Laden.

It is a certainty

that the man who ordered the destruction of the American centers of finance and

of military and political power aimed to create chaos in the United States. The

mass killing of civilians and persons in the military bureaucracy does not

produce a battlefield defeat, as Pearl Harbor did. Although the element of

strategic surprise was the most common characteristic of the two acts, Japan's

ultimate goal was to break down U.S. military power in the Pacific, hence

removing American deterrence from Japanese calculations in Asia. The direct

outcome the jihad war room sought from the events of September 11 was to bring

chaos to the American mainland, leaving U.S. forces around the world untouched.

The real and first objective of the Ghazwa (jihad raid, as Osama called it) was

to trigger a chain of reactions, on both the popular and political levels.

Osama expected up to a million Americans to demonstrate in the streets against

their government, as Israelis had done against their cabinets in the 1980s. He

hoped that Congress would split in two and become paralyzed, campuses would

rebel, and companies would collapse. He wanted chaos and a divided nation,

scared and turning upon itself. He believed, for many reasons, that the time

was ripe for the fall of the giant. (See "Warning to the United

States," October 7, 2001, http://news. bbc.co.uk/l fhi/world/south_asiaJ1585636.stm.)

Based on how things

are dealt with in his part of the world, Osama probably was expecting

Americans to attack Arabs and Muslims in some sort of ethnic strife

model, in which thousands of armed civilians wreak havoc on entire

neighborhoods. He fantasized about Arab and Muslim blood spilled in the streets

of American cities. AI Qaeda projected mass retaliations similar to sectarian

backlashes in the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent. Ironically, in the

first days after September 11 some jihadist callers were reporting alleged

backlashes live to alJazeera. Had such a nightmare

occurred in America, al Qaeda would have ruled in Muslim lands and recruited

hundreds of thousands of new members.

With chaos and ethnic

wounds raging inside the country, the engineer of mass death projected that

America would sow grapes of wrath abroad. Had he had such military power, and

had his "caliphate" been attacked in similar ways, he would have unleashed

Armageddon against the infidel world. Reversing the psychology, bin Laden

expected the U.S. military to carpet bomb Afghanistan and elsewhere. He thought

he would draw the Yankees' raw power into the entire Muslim world and expected

a global intifada to ensue. Interestingly enough, the jihadists anticipated

millions of deaths in Afghanistan and the Middle East. Some indications lead me

to guess that the sultan of the mujahedin wanted the "great Satan" to

do the unthinkable and resort to doomsday devices. (See for example Sulaiman

Abu Ghaith, official spokesperson of the organization in a message aired on alJazeera, October 14,2001, "Retaliation for Air

Strikes on Afghanistan," http://news.bbc.co.uk/lfhi/world/middle_east/

1598146.stm.)

In the web site and alJazeera debates that followed and continue to this day,

we can see the emergence of three remarkably strategic consequences that al

Qaeda hopes for. A long-term "internal" tension in the United States,

one fed by actions such as sniper activities, dirty bombs, and government

reactions, will lead to what they hope will become an "ethnic

crumbling." Once that stage is reached, an irreversible mechanism will

take over. In parallel, a world intifada will explode in several spots fueled

by the jihadists around the world. With these two cataclysmic developments

taking place simultaneously, bin Laden or his successors will hope to witness

the withdrawal of U.S. forces deployed worldwide and the general collapse of

that nation. These end of-times projections were made before September 11 and

resumed afterward, and in fact continue today. They explain clearly the

reasoning behind the attacks on September 11, and subsequent strikes elsewhere

such as the March 11, 2004, bombing in Madrid, the Saudi attacks, as well as

strikes in Turkey, Tunisia, Kashmir, Chechnya, Moscow, London, and the ongoing

bursts in Iraq's Sunni triangle.

However, and as we

will discuss later, what was not on the jihadist map of operations was the

unexpected U.S. reaction and how the American public backed the government's

counteroffensives, as well as the international solidarity with the war on

terror.

For updates click homepage here