By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

Challenges In Drawing Lessons From

History

Why study history? We

hope to better guide our future by understanding the past. History also could

prepare us for action. In this context, the diplomat and historian George F.

Kennan ranks as one of the most influential figures in foreign

policy. Kennan was a sui generis thinker, a trenchant critic of communism

and capitalism, and a pioneering environmentalist. Living between Russia and

the United States, he witnessed firsthand Stalin’s tightening grip on the

Soviet Union, the collapse of Europe during World War II, and the nuclear arms

race of the Cold War.

The history of the

world has evolved through the interactions of billions of individuals, each

pursuing various goals and faced with multiple challenges. We have in this book

spoken a great deal about the challenges but less about the plans – beyond the

basic human needs for food and shelter and certain psychological temptations

that humans commonly face. We reflect here on what world history might tell us

about the purposes of human life.

Individuals, each

pursuing various goals and each faced with multiple challenges. We have in this

book spoken a great deal about the challenges but less about the plans –

beyond the basic human needs for food and shelter and certain psychological

temptations that humans commonly face. We reflect here on what world history

might tell us about the purposes of human life.

It seems worthwhile

to reflect on whether the combined efforts of billions of humans over the

millennia have had any sound effects. We could enhance our confidence that our

actions today will lead to a better future if we identify progress in the past

course of human history.

Making the world a

better place may seem a tall order – though only if we neglect the

evolutionary insight that the world has improved chiefly through multiple minor

changes. It is, therefore, tempting to follow a thought process such as: “I am

an X,”; “The X is worthy,”; or “Therefore, it is meaningful to be an X.” There

is a formidable logic to this source of meaning. And it resonates with the basic

human tendency to identify with groups. It can complement our first source of

sense if it guides us to work toward the prosperity and happiness of group X in

a way that is not harmful to the members of not-X. Humans can accomplish much

when we jointly attach a shared meaning to specific activities. The danger, of

course, is that a strong group identity can guide us toward acts of hostility

toward non-members. It can also steer us away from self-knowledge by

encouraging us to absorb group X’s beliefs and practices without question.

World history provides a set of lessons that should guide us toward a positive

type of group identity:

For example, at the

advanced age of 94, George Kennan was still arguing that the Cold War hadn’t

been inevitable—that it could have been avoided or, at least, ameliorated. A

decade after that 44-year conflict ended, Kennan, the somewhat dovish father of

the United States Cold War containment strategy, contended in a letter to his

more hawkish biographer, John Lewis Gaddis, that while Soviet dictator Joseph

Stalin was alive, an early way out might have been possible.

The so-called Stalin

Note from March 1952—an offer from Moscow to hold talks over the shape of

post-World War II Europe—showed that the United States had ignored the

possibilities of peace accomplished through “negotiation, and

genuine negotiation, in distinction from public posturing (italics

original),” Kennan wrote in 1999.

Those words still

resonate today. Because public posturing is mostly what we’re seeing as the

United States finds itself spiraling toward a new kind of cold war with China

and Russia. Yet almost no debate or discussion about these policies is taking

place in Washington. Especially when it comes to the challenge from China—which

has replaced the Soviet Union as the primary geopolitical threat to the United

States—politicians on both sides of the aisle see political gain in out-hawking

each other by calling for a tougher stance against Beijing. What is emerging,

as a result, is a long-term struggle for global power and influence that could

easily outlast the first Cold War. This is despite President Joe Biden’s

insistence after a November 2022 summit meeting with Chinese leader Xi Jinping

that “there need not be a new Cold War.” When Secretary of State Antony Blinken

makes his first visit to Beijing in a few weeks, it will be an attempt to

repair diplomatic relations suspended since former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s

visit to Taiwan last year.

The reasons for the

ultra-nationalism and anti-Western fervor of Putin and his Kremlin

supporters are complex and reach back deeply into Russian history.

But Kennan may well have been right about the perils of poking the Russian bear

too hard for too long. A little-noted U.S. Army study commissioned by the Trump administration nearly

five years ago anticipated both Putin’s aggression and popular Russian support

for his Ukraine invasion. The study, co-authored by intelligence specialist C.

Anthony Pfaff, concluded that “the Russian people share the same sense of

geographic insecurity and political humiliation as their government [and]

demonstrations of global power and confrontation with the West, especially in

Eastern Europe, will only serve to bolster the popularity of any future Russian

government.”

This realpolitik

sensitivity to other nations’ strategic interests was a constant theme in

Kennan’s thinking. In the late 1950s, in a series of radio addresses that Costigliola writes were “arguably more impressive”

than Kennan’s famed “long telegram” and “X” article laying out the

groundwork for containment, Kennan “shook the very foundations of Cold War

regime in Britain, West Germany, and the United States.” He challenged the

division of Germany into western and eastern halves, the rigid heart of the Cold

War orthodoxy at the time. Kennan proposed that the West and East could find a

way to negotiate a partial disengagement if the Westerners withdrew from

Germany in return for a Soviet military pullback from Eastern Europe. A

reunified Germany that would remain neutral and only lightly armed would be a

buffer, avoiding the brinkmanship that occurred later in 1958-59 and then again

in 1961-62, culminating in the Cuban missile crisis and the threat of

Armageddon. Germany would also not remain in NATO—echoing the deal first

offered by Stalin in 1952. Kennan proposed keeping some nuclear weapons

for deterrence, but he said that tactical nukes would only cement the division

of Europe. He warned that a runaway nuclear arms race would ensue if nothing

were done.

His proposals, the

so-called Reith lectures, never went anywhere—especially after Moscow launched

Sputnik in 1957, raising the threat of nuclear apocalypse on New York and

Washington—and Kennan was accused of Munich-style appeasement. His friend and

strategic archrival, Dean Acheson, complained that Kennan “lived part of the

time in a world of fantasy” and even, at one point, compared his old diplomatic

comrade to a species of ape engaged in “absurd and idle chatter.” Kennan was

devastated and lamented that no one in power was “interested in a

political settlement with the Russians.” The Soviet collapse a little over

three decades later appeared to vindicate Washington’s hard-line

strategy, but people also tend to forget just how close the world came to all-out

nuclear war in the interim.

Kennan also

presciently opposed the Vietnam War. In Senate testimony in 1966 that was so

closely followed around the country that it “pre-empted I Love Lucy,”

Costigliola writes, Kennan declared that containment

did not apply to a civil war in Vietnam that would only damage prestige by

attacking “a poor and helpless people.” Quoting John Quincy Adams, he said the

U.S. should not go “abroad in search of monsters to destroy.” But as with

NATO’s response, U.S. policies were entrenched by then.

The critical question

today is whether Washington’s posture of confrontation is similarly

entrenched. One reason both Democrats and Republicans agree on a harsh response

to China is a mutual sense that Beijing has long duped them. For most of the

last quarter-century, both U.S. political parties were eager to engage China,

only to conclude that its leaders were mainly interested in stealing

intellectual property and building up China’s economy to displace the United

States as the world’s leading power. Biden, accordingly, has populated his

China advisory team with hawks such as Kurt Campbell and Rush Doshi.

Beyond that

bipartisan consensus, there has long been a political bias toward confrontation

over negotiation—at least since former British Prime Minister Neville

Chamberlain gave a bad name to appeasement at Munich. The politics of all

wars—including cold wars—are such that presidents gain an advantage by looking

decisive and tough-minded. The benefits of such an approach are immediate—a

robust and leaderly image for the president and

higher poll ratings—while the costs are long-term and diffuse: ever-worsening

global warming, the slow escalation of an arms race, and the even slower

unraveling of the international system, the vague but increasing threat of

future pandemics. As for a more conciliatory, realpolitik approach, on the

other hand, its benefits are long-term and diffuse, and its costs

immediate: an image of weakness and indecisiveness, which no U.S. president

likes, especially when he’s fighting a war.

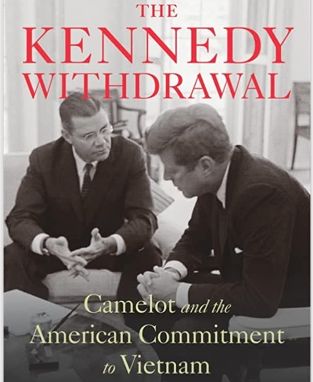

Those questions go to

the heart of a book about the Cold War, The Kennedy Withdrawal: Camelot

and the American Commitment to Vietnam, where it is argued that even

presidents who might realize the potential hazard of overreacting can

nonetheless be pulled in. In his book, Selverstone

dissects one of the last enduring shibboleths of the Cold War: the Camelot myth

that President John F. Kennedy would have avoided the quagmire of Vietnam had

he lived.

True, Kennedy was, by

many accounts, always leery of being pulled into a conflict that he, as a young

senator, recognized was essentially a nationalist movement against French

colonialism. As Silverstone writes, Kennedy told his Senate colleagues as far

back as 1954 that “no amount of American military assistance … can conquer an

enemy which is everywhere and at the same time nowhere.” The Kennedy

Withdrawal: Camelot and the American Commitment to Vietnam. Even so, he was

still a confirmed Cold Warrior, worried about credibility and ready to “pay any

price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support.

Silverstone depicts

Kennedy and his national security team as believers in the “domino theory” that

President Eisenhower first explicated in the 1950s. This theory held that if

South Vietnam fell to the communists, other nations in the region would also

fall like dominoes—one after the other. And in the “long twilight struggle”

(Kennedy’s words) known as the Cold War, the fall of those Asian dominoes would

undermine American credibility worldwide.

Silverstone

challenges what he calls the “Camelot” view of the Kennedy withdrawal—the

notion promoted by Kennedy court historians and partisans that Kennedy was

determined to withdraw U.S. forces from Vietnam, thus avoiding President

Johnson’s quagmire supposedly created in the wake of Kennedy’s assassination.

Very little in history or politics, and very little about the machinations of

the Kennedys is that simple.

As a Senator from

Massachusetts, Kennedy, Silverstone notes, took public positions that “were

sharply critical of the Truman administration--for its handling of the Chinese

civil war . . . and for its handling of the Korean War.” Senator Kennedy was a

foreign policy “hawk” who criticized Eisenhower for not spending enough on

conventional defenses and negligently allowing a “missile gap” to develop in

favor of the Soviet Union. Kennedy ran to the “right” of Vice President Richard

Nixon on foreign policy issues during the 1960 presidential campaign.

President Kennedy, in

his inaugural address, promised to “bear any burden” and “pay any price” to

defend liberty. He significantly increased the number of U.S. military forces

in South Vietnam. Kennedy and some of his advisers characterized the defense of

South Vietnam as a “vital” or “significant” U.S. interest. Silverstone

identifies the considerations that shaped JFK’s approach to Vietnam as

“modernization, foreign aid, counterinsurgency, . . . flexible response . . .

[and] general concerns about credibility and falling dominoes.”

Domestic politics was

never too far away from Kennedy’s consideration of Vietnam or, for that matter,

any other issue. And it was here that Kennedy and his advisers formulated plans

for a symbolic withdrawal of 1000 troops in 1964 or 1965. But Kennedy did not

want to be the president who “lost” Vietnam the way Truman “lost” China. Truman

suffered politically both for the “loss” of China and the stalemate of the

Korean War.

Silverstone notes

that the critical national security document on U.S. policy toward Vietnam

produced by Kennedy’s task force on Southeast Asia was NSAM 52, which “pledged

the administration ‘to prevent Communist domination of South Vietnam; to create

in that country a viable and increasingly democratic society; and to initiate,

on an accelerated basis, a series of mutually supporting actions of a military,

a political, economic, psychological and covert character designed to achieve

this objective.’” Under this plan, the Kennedy administration sent U.S.

servicemen “streaming into South Vietnam.”

Silverstone

criticizes the Kennedy team for their “reluctance to distinguish between

peripheral and state interests” and for developing a habit of using U.S.

military forces to “send signals” of American resolve. Kennedy’s military

“advisers,” Silverstone notes, were engaging in combat, regularly accompanying

South Vietnamese troops into the field against the Viet Cong.

Kennedy consistently

portrayed his administration’s actions as helping South Vietnam “win its

fight.” Kennedy understood the political danger of over-committing American

forces in a country most Americans knew little about. But he also understood

the political minefields of the “falling dominoes” and another Korean War-like stalemate.

Kennedy was nothing if not politically cautious.

Silverstone provides

plenty of evidence for a token Kennedy withdrawal of forces but very little

evidence—other than self-serving recollections of Kenneth O’Donnell, Arthur

Schlesinger, Jr., and the egregious Robert McNamara--that Kennedy intended to

withdraw U.S. military forces from Vietnam. The “Camelot” version of the

Kennedy presidency is as fictitious as the English legend.

The best Silverstone

can do to speculate about JFK’s real intentions in Vietnam. And he suggests

that Kennedy and his national security team would probably have acted based on

the military situation on the ground as it evolved over the next several years.

And it is worth remembering that most of the people advising Lyndon Johnson on

Vietnam after Kennedy’s death were Kennedy’s people.

“Rather than signal

an eagerness to wind down the U.S. assistance effort,” Silverstone concludes,

“the policy of withdrawal—the Kennedy withdrawal—allowed JFK to preserve the

American commitment to Vietnam.” The rest, as they say, is history.

There are, no doubt,

more differences than similarities between the Cold War conflict that pitted the

Soviet Union and the United States against each other and the current tensions

between Beijing and Washington. And yet those differences might offer an even

greater chance for breaking the descent into long-term Sino-American conflict

than existed during the Cold War. In contrast to that earlier era, when the

Soviet Union and the United States lived in entirely separate spheres of

influence, the world economy is well integrated, and both the United States and

China have gained much of their wealth by trading and investing in it. Xi

discovered this anew as the Chinese economy slowed dramatically last year, and

its population shrank. Moreover, the new challenges demanding sustained

international cooperation—in particular, stopping climate change and future

pandemics—are far more pressing than they were then. Indeed, it is very likely

that the threats from global warming and new COVID-like viruses are far greater

than the strategic threat that China and the United States pose to each other.

Unlike the Soviet

Union, which surrounded itself with cooperative, tightly controlled

governments, China today finds itself virtually surrounded by U.S. allies or

Westernized states that counterbalance its growing military power. The Biden

administration has already laid down a strict policy approach to China,

including helping arm Australia and Japan; forming the Quadrilateral Security

Dialogue with Japan, India, and Australia; and orchestrating an unprecedented

decoupling of high-tech trade with China, including a frankly protectionist

industrial policy aimed at boosting U.S. competitiveness.

Friend, oppose any

foe to assure the survival and success of liberty,” as Kennedy declared in his

inaugural address. Selverstone argues that Kennedy

“continued to operate from a worldview that embraced the precepts of domino

thinking … and the demonstration of resolve.” Costigliola

notes that Kennedy shied away from embracing Kennan because the latter

supported “disengagement.”

But other scholars

disagree. Harvard University historian Fredrik Logevall,

author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Embers of War: The Fall of an

Empire and the Making of America’s Vietnam, and a not

fully completed two-volume biography of Kennedy, said that Kennedy was a far

more subtle student of history than former President Lyndon B. Johnson and was

skeptical of the domino theory. He believes Kennedy would have found a way to

scale down the U.S. presence in an unwinnable war. “I don’t think the Cold War

was inevitable, and I don’t believe a major U.S. war in Vietnam was

inevitable,” Logevall said in an email.

What do you think

about it now? Just as Acheson and others argued about the Soviet Union during

the Cold War, many policymakers today say that China under Xi seeks only to buy

time while it grows stronger vis-a-vis U.S. power—and then strikes against

Taiwan. Beyond that, Beijing is looking to supplant the United States as the

world’s leading power, no matter what it takes, the hawks say. And Xi is

marrying his vast, technologically advanced economy with Russia’s resource-rich

state to see this ambition through.

Perhaps. But it is

worth noting that while Beijing has backed Putin rhetorically, it has not

delivered military or much economic aid to Moscow’s aggression in Ukraine. The

China-Russia partnership may be flimsy as the Sino-Soviet association did in

the early Cold War. Meanwhile, the Biden administration’s apparent preference

for public posturing over genuine efforts at a realist approach—negotiating a

modus vivendi with China and, perhaps someday, a post-Putin Russia—poses

serious risks. Once again, with almost no debate in Washington or other Western

capitals, NATO plays a controversial role.

Although the alliance

was expressly designed for threats across the “north Atlantic,” to little

notice last summer, NATO expanded its focus to what was effectively a new

containment policy toward China. At its summit in Madrid, the alliance invited

the leaders of Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand to join in for

the first time, and NATO’s new “strategic

concept” named China as one of its priorities, saying Beijing’s ambitions

challenge the West’s “interests, security, and values.”

If Biden doesn’t want

a new cold war, it would hardly be surprising if Xi thought he did. And yet,

with Xi on a back foot because of his disastrous COVID shutdown and a sagging

economy, new possibilities for diplomatic engagement may now exist. “I do not

think Xi sees himself or China in an existential struggle with the United

States over competing for ideological systems,” Leffler said. “I do not think

Xi thinks American and Chinese interests are mutually exclusive.” Or, as Kennan

would put it, according to Frank Costigliola’s

book, “sharply opposed positions are just the asking price in the long,

necessarily patient process of diplomacy.” One thing is certain: We won’t

know for sure unless serious diplomacy is attempted if Kennan were alive today

if he would agree.

For updates click hompage here