Over the nearly two

thousand years of the development of the religion of Daoism many denominations

and sects have come into being due to differences in interpretations of

teachings, lineages, and transmission, and methods of organizing and forming

institutions. There are eighty-six denominations and sects recorded in

documents at White Cloud Temple in Beijing. After the 15th century, more

eclectic sects emerged among the people because of Daoist intercourse with

Confucianism and Buddhism. Among these numerous sects, some were named after

famous historical masters, some after their places of origin, some after

particular Daoist scriptures they followed, and some after cultivation methods.

However, throughout history there have been only four widely recognized major

denominations, which can be categorized in turn under one of the two systems of

Zhengyi Dao (Orthodox Unity Dao) and Quanzhen Dao

(Complete Realization Dao). Zhengyi Dao evolved directly from the Celestial

Masters Way In the middle of the 3rd century, central China was reunited after

many decades of war and chaos.

Many wrote new

treatises on Daoist tenets and many Daoist ceremonies and ritual practices were

accordingly adjusted. Thus, during this period of fragmentation of China

following the four centuries of the Han, a Daoist reformation took place, with

thinkers like Gehong (284-364), of the Eastern Jin

dynasty, Kou Qianzhi (365-448), of the Northern Wei

dynasty, Lu Xiujing (406-477), of the Liu Song

dynasty, and Tao Hongjin (456-536), of the Liang

dynasty leading the way. The inner and outer chapters of Baopuzi

(The Philosopher Who Embraces Simplicity) by Gehong

were canonized by later Daoists as major theoretical

works. Gehong shifted the goal of Daoist ideology

from a pursuit of millennial salvation to one of personal delivery and

immortality. He argued eloquently for the existence of immortals and the

possibility of immortality through self-cultivation, and meticulously itemized

various methods of cultivation and alchemy. He also re-annotated Daoist

theological works according to Confucian thought, argued Daoist cultivation

practice was consistent with Confucian morality, and accepted Confucian norms

of righteous words and deeds as being a necessary precondition of cultivation.

Yan Dynasty relief of Daoist subjects:

In the 2nd century,

the books that were canonized by the earliest Daoist religious sects, the Five

Bushels Sect and the Supreme Peace Sect, were the Book of Supreme Peace, and

the Daode ling and its commentaries,

such as those of Xiang'er and Heshanggong.

Since its first appearance, the Book of Supreme Peace has had many

different names and versions, while the Daode

ling has been the text most widely propagated and explicated by Daoist

masters and their followers from varying perspectives. Among the commentaries

available today, that of Heshanggong (literally, the

"Revered Old Man by the River"), was the first to explain the Daodeling from the perspective of Huang-Lao

Daoism. This commentary, which is commonly regarded as a work edited during the

middle of the Later Han dynasty, formulated the theory of "identification

of body and state," which proposed that the principles of cultivation of

personal health and state management are identical in that both require purity,

reduction of desire, and accomplishment by means of wu

wei.

The number of Daoist

scriptures increased with the development and spread of Daoism. During the

Eastern Jin dynasty, Gehong listed a catalogue of

1299 scrolls of Daoist books in the "Further Reading" chapter of his The

Philosopher Who Embraces Simplicity. With the rapid spread of the Zhengyi

Sect, Daoist charms and liturgies had been further elaborated on, resulting in

the production of a many classics. These works come from three major

traditions: Shangqing, Lingbao, and Sanhuang. The Shangqing tradition

honored its founder, Madam Wei, who ascended on the Southern Sacred Mountain.

Its exponents, among whom were Yangxi and Xumi, composed many works in Madam Wei's name.

The Lingbao tradition

claimed that its earliest scripture had been found in a stone city by Helu,

King of the State of Wu during the Warring States Period. The Supreme Master

Lao had sent Three Sage-Perfect Men to grant many scriptures to Gexuan, who had practiced cultivation at Tiantai Mountain. The Lingbao tradition continued to amass

scriptures as well.

The Sanhuang tradition honored Baoliang,

father-in-law of Gehong, as its founder. There are

different stories concerning the origin of these scriptures: one held that they

were found in a stone house on the central sacred mountain by Baoliang in 292 AD; the other is that they were granted to Baoliang by his teacher, Zuo Yuanfang,

or Zhengying, an occult practitioner of the Later Han

dynasty The majority of the contents of the Sanhuang

scriptures concern rituals of exorcism, charms, talismans, and cultivation

methods based of concentration on deities. All of the scriptures of these three

traditions converged into the Daoist Canon. The compilation of the Daoist

Canon began during the Tang dynasty, when Daoism had its first prosperous

period. Under the powerful patronage of emperors of the Li family, the

collection and compilation of Daoist scriptures reached new heights. Tang

Emperor Xuanzong ordered Shi Chongxuan and another 40

scholars to compile a complete set of Daoist scriptures during his Kaiyuan era

(713-741). Using this work of 113 scrolls as a base, he sent researchers into

provinces to bring back more Daoist texts. These were then compiled into the

first Daoist Canon, the Exquisite Compendium of Three Insights. "Insight"

is a translation of the Chinese dong, which many Western scholars

translate as "grottoes," because the basic meaning of dong is

"cave" or "grotto." However, in this sense it is equivalent

to tong, which means "to communicate." Thus the "three

insights" (sandong) are actually three

ways of communicating with deities, in other words, three insights into the

supernatural. These texts are all believed to be revelations from deities. The

total number of scrolls recorded was 3744, which were classified according to

their contents into three canons, each with 36 subdivisions: Insights into

the Perfect, with 12 subdivisions; Insights into the Mysterious, with

12 subdivisions; and Insights into the Sacred, with 12 subdivisions. It

was titled the Daoist Canon of Kaiyuan because it was printed in the

Kaiyuan era.

The Song dynasty is

the second period of the expansion and promotion of Daoism. Daoist canons were

compiled on six occasions during the Song: 1) In the early years of the Song

dynasty, Emperor Taizong ordered officials of all

local governments to search for Daoist texts. More than 7000 scrolls were

collected. After making many amendments, duplicates were expunged, resulting in

a compilation of 3737 scrolls. 2) In 1008, a further supplement reached 4359

total scrolls. 3) In 1012, this work was again supplemented to become the Precious

Canon of the Celestial Palace of the Great Song, in 4565 scrolls. 4) For

the convenience of the emperor's reading, chief editor Zhang junfang extracted 122 scrolls from the more than 700

designated as the most important classics in the Great Song compilation,

resulting in the Yunji Qiqian

(literally, Cloud Chests with Seven Labels) in fact meaning a

complete Daoist canon, but popularly referred to as the Small Daoist Canon. 5)

During the reign of Emperor Song Huizong, who as an ardent believer in Daoism,

the Daoist Canon was re-compiled twice; the 6455 scrolls. The recent

edition of the Xuandu Canon, compiled

in 1244 during the Yuan Dynasty, contained 7800 scrolls and was supplemented

with scriptures of the Quanzhen sect that was in

ascendancy at that time.

These editions of the

Daoist Canon have mostly been lost; only a few remnant scrolls survive.

The available editions today are the Zhentong

Daoist Canon and Wanli Supplementary Daoist Canon. These are fruits

of projects undertaken under Ming rulers Yingzong in

the 15th century and Shenzong in the 17th century The

total of the two editions is 5485 scrolls.

The scriptures were

arranged in Three Insights or Three Primary Canons, Four Secondary

Canons, and Twelve Accessory Canons. The so-called Three Insights

or Three Primary Canons followed the classification system of past

editions. All scriptures believed to be granted by the Heavenly Sage of the

Pre-existence (Yuanshi Tianzun)

were included in Insights into the Perfect, of which most were from the

Lingbao tradition; all scriptures that were believed to be bestowed by Supreme

Master of Dao (Heavenly Sage of the Lingbao) were classified as Insights

into the Mysterious, of which most were from the Lingbao tradition; all

scriptures that were believed to be granted by Supreme Master of Lao were

classified as Insights into the Sacred, of which most were from the Sanhuang tradition. The so-called Four Secondary Canons include

Great Purity, Great Peace, Great Mystery, and Zhengyi canons. All

books in these canons were expository and complementary to one or more of the Three

Insights. Great Purity texts were expository and complementary to Insights

into the Perfect; Great Peace texts to Insights into the Mysterious;

Great Mystery texts to Insights into the Sacred; and Zhengyi to

all Three Insights. Twelve Accessory Canons were miscellaneous

scriptures that could not be classified into the Three Insights Oy the Four

Secondary Canons.

Kou Qianzhi lived in the years of the split between the

Southern and Northern dynasties. Supported by imperial family members and

nobles of the Northern dynasty, he claimed to have been visited by Supreme

Master Lao, who gave him the title of Celestial Master, along with the New

Musical Liturgy of Commandments from the Clouds (clouds representing the

heavenly realm), a classic in 20 scrolls. He courageously reformed the

teachings of the Celestial Masters Way (now Datong in Shanxi Province) during the Northern

Wei dynasty Kou successfully effected the unification of Daoism with feudal

power. Lu Xiujing lived in southern China. His major

contribution was to inherit and develop Gehong's

theories and apply them in the reformation of extant Daoist organizations. He

collected large numbers of Daoist scriptures and improved liturgies. His

reformed Daoism is called the Southern Celestial Masters Way.

Tao Hongjing enriched and developed Daoist cosmology on the

basis of Laozi and the Yijing (Book of

Changes). He was among the earliest advocates for the unification of

Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism. In his Catalogue of the Daoist Pantheon,

he arranged various Daoist deities into a great hierarchical system for the

first time, and promoted the unification and systematization of Daoist

theories.

In 364, during the

Eastern Jin dynasty, a Daoist priest named Yangxi

claimed that the goddess Madam Wei had given him a scripture in 31 scrolls

titled the True Book of Shangqing (shangqing means "supreme purity"). He

subsequently founded the Shangqing Sect, which took

the True Book of Shangqing as its central

text, promoted the Heavenly King of the Origin and Supreme Master Lao as its

two highest celestial gods, and adopted a practice called cunxiang

as its chief method of cultivation. By this method, a practitioner can

guide celestial gods into his body and communicate with the gods of his own

internal organs. The practitioners internal gods report his or her behavior to

the celestial gods, who in turn raise or lower the practitioner's status.

Followers continue with this practice until they are ready to ascend to heaven

as immortals. As this practice became more widespread, the sect became popular

on Mount Mao, in Jiangsu Province.

There are some Daoists who have chosen the Sacred Jewel Scriptures as

their central texts. This tradition is the called Lingbao Sect (lingbao translates roughly as "sacred

jewel"). lts main characteristics include

declaring universal salvation, paying special attention to liturgies and

rituals, and emphasizing moral conversions. lts most

sacred mountain is Mount Gezao in Jiangxi Province.

Many other Daoist sects, including the Pure Bright Qingming) Sect, the Highest

Heaven (Shenxiao) Sect, the Dragon Tiger (Longhu) Sect, the Wudang Sect

(which originated at Mount Wudang), and the Pure

Beauty (Qingwei) Sect, continued to emerge throughout

the jin, Tang, and Song dynasties. They both

coexisted and communicated, learning from each other.

This changed in 1304,

during Yuan Dynasty, when the emperor granted the honorific title of Orthodoxy

Oneness Lord (Zhengyi Lord) to Zhang Yucai, the 38th

generation Celestial Master, and placed him in charge of all Daoist sects in

China. Since then, Southern and Northern Celestial Master Sects, the Shangqing Sect, and the Lingbao Sect, have been generally

called Zhengyi Dao. Their common characteristics are: they take Zhengyi

classics as their central scriptures; they undertake liturgy and exorcist

rituals as their major religious services; their clerics are allowed to marry

and have children; they are not forced to live in temples and lead monastic

lives; and their commandments are not particularly strict. Zhengyi Dao is the

general name for all kinds of talismanic sects directed from Mount Dragon and

Tiger, formed after Daoism had already entered a relatively mature stage. Among

the sects in this denomination, some have preserved their own unique tenets and

liturgies, whilst others have conformed to Zhengyi norms.

There were once other

important Daoist sects in China, among which the most famous were Taiyi (Great Unity) Daoism, and Zhenda

(True Great) Daoism. However, they only survive in various forms on Taiwan, and

only the Zhengyi Dao and Quanzhen Dao denominations

have survived in mainland China.

In 1900, when Western

forces invaded Beijing, the wooden printing blocks of the Zhentong

Daoist Canon and the Wanli Supplementary Daoist Canon were burned.

Only one set of the Daoist Canon from the Ming was kept preserved, at

the White Cloud Temple. From 1923 to 1936, in order to rescue this cultural

heritage, Zhao Erxun and other important scholars

initiated a program of reprinting these texts. Using the Daoist Canon of White

Cloud Temple as the source, they engaged Hanfenlou

Bookstore in Shanghai to reprint 350 sets, each with 1120 volumes. These copies

were called the Hanfenlou edition, which is the major

version of the Daoist Canon available today. The familiar classics such

as Daode Jing, Zhuangzi, Book oJ Divine Deliverance, Classic oJ

Pure Quit, and Book of the Intuitive Enlightenment, are all included

in this collection.

Although there was no

new compilation of the Daoist Canon undertaken in Qing dynasty, some

important reference works were published, including the Compilation oJ Important Books in the Daoist Canon, the Contents

oJ the Compilation oJ

Important Books in the Daoist Canon, and the Basic Index oJ Compilation oJ Important Books

in the Daoist Canon. The earliest edition of the Compilation of

Important Books in the Daoist Canon was completed by abstracting 173 books

from the Daoist Canon of the Ming during the Jiaqing

era (1796-1820). This collection was gradually supplemented, reaGhing 287 volumes in 1906. Since none of the 114 books

which were added were included in the Ming dynasty Daoist Canon, they

naturally became important materials for the study of Daoism during the Ming

and Qing dynasties.

Another important

event during the Qing dynasty was the discovery at the beginning of the 20th

century by a Daoist monk named Wang Yuanlu of ancient

scrolls in cave number 17 at Mogao Caves at Dunhuang, in western China. Some

long-lost Daoist classics were found among these scrolls, which are now called

the Dunhuang Daoist Scriptures. These books, numbering 496 items, are

hand-written, and date from the 6th to the 10th century, mostly from the reigns

of Gaozong and Xuanzong of the Tang dynasty Most of them are fragmentary, yet

they remain important relics of great historical value for Daoist studies, and

are crucial for both supplementing and collating the Daoist Canon of the

Ming dynasty Unfortunately, as a result of political corruption during the Qing

dynasty, these scrolls were stolen from China, a first large batch by the

British explorer Aurel Stein in 1907, and subsequently more scrolls by a

Frenchman, Paul Pelliot, then a Russian, Pyotr

Koslov, and finally a Japanese, Zuicho Tachibana.

After the establishment of People's Republic of China, through the joint

efforts of the Chinese government and overseas friends, a small number of the

priceless Dunhuang scrolls have been brought back to their homeland and

preserved.

The Quanzhen and Zhengyi sects have their own specific

succession systems and liturgies; those of Quanzhen

are called chuanjie (literally,

"to pass down commandments"), while those of Zhengyi are called shoulu (literally, "to bestow the sacred

registry"). The system of chuanjie in

Quanzhen Daoism, founded by Qiu ehuji

in the 13th century, has a history of over 700 years; and that of shoulu in Zhengyi Daoism, founded by Zhang

Daoling in the 2nd century, has a history of over 1800 years. The shoulu assemblies were often held on the days

before Triplet Days, because these are occasions when the Three Elements Gods

inspect human deeds and determine blessings and punishments accordingly

It subsequently

became a custom for the Celestial Masters to descend to altars to bestow sacred

registries in the Mansion on Mount Dragon and Tiger on the Triplet Days. Lu is

an entry in the registry book of deities from all directions, but also the

certificate to summon divine generals to execute Daoist orders. Zhengyi Daoists believe that only after having been bestowed with lu can they ascend-to the Heavenly Court and

get divine positions. Only those who have divine positions can make their

memorials to Heaven heard or seen in ceremonies, and thereby command divine

soldiers or generals.

Shoulu ceremonies

are presided over by the Three Masters, of Proselytism, Inspection, and

Recommendation. Since the 24th generation, the Celestial Master was authorized

by Emperor Zhengzong of the Northern Song Cr.

997-1022) to set up a shoulu court in

the capital city, and in these ceremonies the Proselytizing Master has always

been played by the Celestial Masters themselves.

In the Daoist

tradition, chuanjie and shoulu are not only ordination ceremonies

which call for participants' belief in Dao and their commitment to priesthood,

but also educational ceremonies to regulate the words and deeds of priests. In

modern times, war and chaotic conditions halted the practice of these rituals

for decades. Although the White Cloud Temple in Beijing was the central place

for chuanjie, no such ceremony had been

held since the 1920s.

More recently then,

following the founding of the Government sponsored Chinese Taoist Association traditional

systems and rituals that had not been practiced since the 1920’s a chuanjie ceremony was first re-introduced

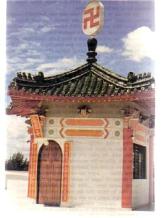

again on Dec. 2, 1989 see picture:

Since then the Chinese

Taoist Association CTA has grown into an International organization and March

17th to 20th, 2003, the CTA hosted a ‘Laozi’ Celebration where concerts were

performed by Daoist orchestras of White Cloud Temple in Beijing, Mount Mao in jiangsu, Xuanmiao Temple in

Suzhou, Mount Mian in Shanxi, the Hong Kong Penglai Daoist Temple, Gaoxiong

Culture Institute, Wall and Moat God Temple in Singapore, and the Choir of Daode jing of Dashibo

Palace in Singapore.

Continue to History of Early Taoism, Tantra, and

Buddhism Project, P.1:

For updates

click homepage here