The following is a

continuation of our our original six part Global Jihad study whereby we investigate here by

analyzing the original writings, that is what is considered the original

version (although even there varying opinions exist) of Islam.

Historically, Muslims

have dealt with questions about right and wrong in a variety of ways. Early on,

Islamic civilization produced a number of exceptional philosophers. The great

al-Farabi (d. 945) modeled his work The Virtuous City on Plato's dialogue Laws.

Ibn Sina (d. 1045) wrote on medicine and politics. Ibn Rushd (d. 1145) composed

a number of important and innovative commentaries on the works of

Aristotle.1Even more substantial is the literature Muslims call adab, letters, the reflections of cultivated and learned

people on the manners and morals appropriate to particular issues and types of

work. Thus, al-Jahiz (d. 839) compiled a formidable collection of tales about

miserly behavior, the moral import of which was to demonstrate the problems

stemming from a lack of generosity. Others wrote works reflecting on the

professional ethics appropriate to the practice of medicine. Still others

composed "mirrors for princes;' reflecting on the problems of statecraft.2

Alongside these modes

of reflection is another that stands out partly because of its endurance and

partly because of its contemporary significance. This is the way of thinking I

call Shari'a reasoning. Al-shari'a

is usually translated as Islamic "law."3 But it is more than that.

Literally, al-shari'a means "the path." In

a more extended sense, it refers to the path that "leads to refreshment:'

With the advent of Islam, this extended sense lent itself to the notion of a

path ding to "success;' a way to paradise, a way associated with happi5S

in this world and the next. AI-shari'a is thus a

metaphorical representation of a mode of behavior that leads to salvation. As

the lr'an has it, those who walk the "straight

path" (sirat al-mustaqim)

are "successful" with respect to the judgment of God (1:6-7).

More prosaically, al-shari'a stands for the notion that there is a ht way to live. The good life is not a matter of behaving

in whatever ways human beings may dream up. It is a matter of

"walking" in the way approved by God; or, reflecting the notion of

Islam as the natural religion, the good life involves behavior that is

consistent with the status of human beings as creatures. As Muslim theologians d it, it is possible to imagine God creating other worlds,

in which creatures unlike human beings might be judged according to a different

standard.4 Once God created the world in which we live, however, he did so in a

way that distinguished right from wrong, good and evil. Further, God set these

distinctions in the context of a world that ultimately moves toward judgment.

On the great and sintar day which the Qur' an speaks of in terms such as al-akhira

(thereafter) or yawm aI-din

(the Day of Judgment or of Justice), hum beings will see clearly the rewards or

punishments they have aquired by acting in certain ways.

Given such notions, it is hardly strange to find Muslims inquiring out right

and wrong very early on. The Qur' an summoned its

hearers to right behavior and exhorted believers to refer questions to God and

God's Prophet. Indeed, the Qur'an indicates that submission is measured in

terms of obedience to these two sources, which Muslim tradition came to

associate with the Qur' an and with the sunna, or example of Muhammad, particularly as related in ahadith, or reports, of the Prophet's words and deeds, as

witnessed by his companions.

From very early on,

then, Muslim inquiry regarding right and wrong was associated with the

interpretation of texts. Not surprisingly, a class of specialists emerged,

trained in the reading and interpretation of the Qur'an and ahadith.

The 'ulama, or learned ones, became an important resource for a community

devoted to inquiry regarding the Shari'a,

particularly in contexts where literacy levels were low, and where the

available means of book production made texts rare and expensive. More

recently, however, groups of "lay" Muslims have asserted their right

and duty to read and interpret, sometimes in conversation with the 'ulama, and

sometimes in opposition to them. As such groups have it, comprehension of the Shari'a is the duty of all Muslims, who must read and

interpret the sacred texts to the best of their ability. As we move through the

twentieth and into the twenty-first century, the participation of such groups

must be viewed as one of the most important developments in the story of Shari'a reasoning.

When Umar, second

leader after the Prophet, died in 644, the first wave of Muslim expansion was drawing to a

close. According to standard tradition, 'Uthman, as third leader, inherited

'Umar's system of administering the newly established Muslim regimes. In this

system, a centrally located group of officials, buttressed by a military

presence, governed a prescribed territory.

Income from taxes

levied on land held by (pre-Islamic) residents of each territory provided both funding

for local administration and revenues to the leader in Medina. The latter used

these funds to support further expansion, in line with the mission of Islam.

In each territory,

the establishment of a new administration bore witness to the hegemony of

Islam; the priority of Islamic values provided legitimacy for political

authority. Territorial governors, along with the fighters supporting them,

conducted prayers after the pattern established in the Arabian Peninsula. Along

with the prayers came religious instruction. In this connection, the foremost

activity, requiring the specialized knowledge of teachers, was recitation of

the Qur' an. Although it is difficult to evaluate the

traditional report that credits 'Uthman with standardizing the written text of

the Qur' an, it makes sense that systematization of

the scriptural text would coincide with the expansion of Islam. When

pre-Islamic residents of the territories converted to Islam-and certainly some

did-the specialists trained in reciting the Qur' an

acquired additional authority and importance.5

Given the report of

'Uthman's role in establishing the Qur'anic text, it is ironic that opposition

to his rule developed around the charge that he failed to govern by the Book of

God. In 656 a group of fighters dissatisfied with the administration of affairs

in Egypt came to Medina, seeking 'Uthman's intervention. Seemingly satisfied

with his response, the group began the return journey. Along the way, it seems

they began to doubt the leader's intention to carry through as promised. Some

returned to Medina and assassinated 'Uthman.6

By prior agreement,

leadership passed to 'Ali ibn Abi Talib, the cousin of Muhammad and one of the

earliest converts to the prophetic mission. 'Ali sought reconciliation with

those responsible for 'Uthman's death. In doing so he offended the members of 'Uthman's

family, in particular the territorial governor of Syria. Mu'awiya, arguing that

'Ali's failure to punish the rebels constituted a failure of justice, brought

his army to challenge the leader. As the opposing forces approached each other,

ready for battle, Mu'awiya's men placed copies of the Qur'

an on their lance points and advanced, chanting "Let the Qur'an

decide!" 'Ali accepted the challenge, thereby sending the dispute to

arbitration. Conducted by those who knew the Qur' an

best, the judgment nevertheless failed to provide a clear resolution. Even

more, the process of arbitration led to further divisions among the Muslims, so

that a certain number seceded from the ranks of 'Ali's supporters, declaring

themselves bound only by God and God's Book. These Kharijites (al-khawarij, those who exited) constituted a kind of pious

opposition. In the ensuing strife, they declared themselves opposed to both

sides. In the end, however, their activities did more harm to 'Ali than to

Mu'awiya. One of their number assassinated the fourth leader in 661.

Thus began a period

of great disorder, which in Islamic tradition received the name "first fitnd' -what one might call a civil war-as various groups

competed for power. Of these, Mu'awiya's was the strongest, not least because

the territory of Syria provided economic resources superior to those elsewhere.

When the Syrian forces, by now commanded by Mu'awiya's son Yazid, destroyed the

army of 'Ali's son Husayn at Karbala (in southern Iraq) in 680, the great

conflict was, for all practical purposes, resolved. Rebel forces in Iraq and in

the holy cities of Arabia continued to mount an intermittent resistance, and in

692 'Abd aI-Malik even attacked the Ka'ba to put down

a rebellion. Nevertheless, for the next sixty years (that is, until the 740s)

the political and military epicenter of Islam would be Damascus. Polemics

between the two most important divisions within Islam take the events of this

first fitna as a point of departure. The Shi'a, or

partisans of 'Ali, claim that the victory of Mu'awiya and his descendants

constituted a rejection of right leadership, and thus a departure from the

Prophet's (and God's) design for the Muslim community. Sunni Muslims, or, as

the traditional description has it, "the people of the prophetic example

and the consensus (of the Muslims)" (ahl al-sunna

wa' I-jama'a), also

perceive these early struggles as critical, though typically they assign blame

to all involved. Both labels, Sunni and Shi'i, cover a multitude of

subgroupings, and their use with respect to Muslims in this very early period

is not entirely appropriate. But the labels would emerge strongly as the

different perspectives of these divisions became relevant to the development of

Shari'a reasoning.

More interesting is

the clear priority of the Qur' an in arguments about

right and wrong, even in this very early period. The slogan "Let the

Qur'an decide!" indicates that most Muslims recognized the relevance of

the revealed text in ascertaining guidance. Similarly, the role of the mediators

in the dispute provides a glimpse of the importance of a class of specialists

whose role was to preserve and recite the Qur' anic text. The importance of this class increased with the

consolidation of power by Mu'awiya's descendants in Damascus. Sometimes known

as the Marwanids, and more typically as the Umayyads, these constituted the

first imperial rulers in Islam. As their critics put it, with the Umayyads,

leadership changed from al-khilafat, or governance by one fit to be called the

successor to Muhammad, to al-mulk, the kingship,

meaning a system in which leadership is passed from father to son, without

concern about qualities of character. The Umayyads, of course, preferred to

cast their regime as alkhilafat, and presented

themselves as God's appointed rulers. In court poetry from the time, we read

propaganda consistent with this claim:

The earth is God's.

He has entrusted it to his khalifa.

The one who is head in it will not be overcome.?

God has garlanded you [Umayyad rulers] with the khilafa

and guidance;

For what God decrees, there is no change.8

We [God] have found the sons of Marwan [Umayyads] pillars of our religion,

As the earth has mountains for its pillars.9 Were it not for the caliph and the

Qur' and he recites, the people had no judgments

established for them and no communal worship.10

Of course, recitation

of the Qur' an was not

confined to the caliph. The class of specialists responsible for it was to some

extent sponsored by Umayyad rulers, as is suggested in this poetry.

Nevertheless, some reciters apparently maintained an independent center of

power. One of the first of these independent scholars was aI-Hasan

al Basri (d. 728). As the name indicates, al-Hasan's location was Basra, in the

south of Iraq, the geographic center of resistance to the Umayyads. Al-Hasan's

fame seems to exceed our actual information about him. Subsequent generations

have claimed him as the inspiration for Sufism, that peculiar form of popular

Islam that gained a massive following in later centuries. At the same time,

various Sunni and Shi'i groups claim aI-Hasan as one

of the early advocates of their favorite doctrines.l1 His exploits are

legendary, and sayings attributed to him often cryptic. What does seem clear is

that aI-Hasan functioned as a critic of some Umayyad

claims, and that he did so in a way that advanced the notion that learning

itself constitutes a kind of authority. When asked about Umayyad claims to

divine legitimacy, aI-Hasan supposedly said:

"There is no obedience owed to a creature in respect of a sin against the

Creator;' thus pointing to a limit on Umayyad (or other human) authority. That

this claim follows from the Qur'anic text seems obvious; after all, there is no

god but God.12

As noted, aI-Hasan claimed authority on the basis of 'jIm, or knowledge, and specifically of knowledge of Islamic

texts. By the 730s the phenomenon of authority based on learning was

widespread, with particular centers in Damascus (or, more generally, Syria),

Iraq, and the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.

We know only a little

about the activities of scholars in Damascus. Local traditions focus on a

figure called al-Awza'i, who is cited as the founder

of a distinctive approach to Shari'a reasoning. No

works of al-Awza'i are available to us, though some

of his opinions are quoted by other scholars. We can surmise that there was a

sustained conversation between Muslims and Christians (and perhaps Jews) in the

region, not least because works by John of Damascus (d. 750), a prominent

Christian theologian, are posed in terms of dialogues between scholars of these

traditions concerning issues related to the attributes of God.13 These

dialogues (and, one assumes, the attendant discussions) would become important

in the development of Shari'a reasoning somewhat

later, in the ninth century.

The most notable

learned figure in Mecca and Medina at this time was Malik ibn Anas (d. 795).

Here again, information is not extensive. If we take Malik's great work, aI-Muwatta (The Well-Trodden), as representative, it seems

clear that some Muslim scholars were developing a way of thinking in which

verses from the Qur' an were connected with, and thus

interpreted through, reports of the practice of Muhammad, his companions, and

the continuing tradition of practice of the Muslims in Mecca and Medina.14

By contrast with

Damascus and with the holy cities, we have a great deal of information

regarding Iraq. If we take aI-Hasan al-Basri less as

an individual, and more as a "type;' representative of the behavior of a

group of learned people in the first half of the eighth century, we begin to

see the lines of a religious critique of Umayyad rule. Indeed, much of what we

have from later generations of Muslims suggests that scholars located in Iraq

in the 720s and 730s spent a great deal of time and energy discussing the

grounds of such criticism and, beyond this, the proper mode of resistance to

what they deemed illegitimate rule. One must use such reports with caution, of

course, as later generations often read back into the eighth century something

of their own concerns-such as the tendency of various groups to claim al-Hasan

al-Basri as the source of their own movements. There is no reason to doubt,

however, that numbers of religious specialists in Iraq constituted an

intellectual wing of a growing "pious opposition" to Umayyad rule.

Our information about these is connected to the success of the Abbasid revolt,

which by the late 740s or early 750s attained a level of success sufficient for

historians to speak of a relocation of power in the Islamic empire from

Damascus to Baghdad, and from the Umayyad to the Abbasid clan.

By the time the

Abbasid clan established its khilafat, there was a growing class of religious

specialists in Iraq, claiming the authority to distinguish right from wrong on

the basis of religious knowledge. All of these connected authority with the

text of the Qur' an, and the Abbasids took note of

this fact. They promoted their cause by promising to establish "government

by the Book of God." Having acknowledged the priority of the Qur'an,

however, those claiming authority by reason of knowledge differed considerably

in approach. Some, who came to be associated with the kind of the dialectical

theology Muslims called al-kalam, literally "speech" but in this

context "theological disputation," held that the import of the Qur' an was best extracted

through a process of rigorous, systematic argument. The most influential of

these, in the early years of Abbasid rule, came to be known as Mu'tazilites, separatists. Mu'tazilites

focused on clarifying the system of doctrine outlined in the Qur' an. Their interpretations are not themselves an

example of Shari'a reasoning, though they had clear

political import and, through the ministrations of the Abbasid caliphs, would

come to playa critical role in the development of the

practice. For late eighth-century examples of Shari'a

reasoning, we must turn to a different circle of Iraqi scholars, of whom the

most famous were Abu Hanifa (d. 767), Abu Yusuf (d. 798), and al-Shaybani (d. 804). Muslim sources assign credit to the

first of these as the founder of the circle, which eventually came to bear his

name. Abu Yusuf and al-Shaybani were the two greatest

students of Abu Hanifa, and their works bear witness to the approach taken in

his "school:' Two such works are particularly important. Abu Yusuf's Kitab

al-kharaj deals with the administration of

territories in which an Islamic regime comes to power. It thus reflects a

continuing discussion regarding governance of conquered or liberated areas.15

Al-Shaybani's Kitab al-Siyar, by contrast, deals with

"movements" or "relations" between territories. Al-Shaybani was thus interested in international relations.

Indeed, the modern historian of international relations Majid Khadduri once

spoke of this early Iraqi scholar as the Hugo Grotius of Islam, implying that

al-Shaybani stands to the development of an Islamic

"public international law" as does Grotius to the development of the

Western version of such norms. 16 Whether or not Khadduri's comparison is apt,

it is true that al-Shaybani's work reflects judgments

or opinions on a number of important political and military topics: the

declaration and conduct of war, the status of treaties between rulers, grants

of safe passage for persons traveling from one territory to another for purposes

of diplomacy, trade, and the like are all at issue, as are matters of policy

within Islamic territory-for example, the status of rebels, the collection of

taxes, and the obligations of Jews, Christians, and other "protected"

communities.17

In the works of Abu

Yusuf and al-Shaybani, we see the emergence of a

specific class of religious specialists, and also of a particular style of

reasoning about matters of right and wrong. Al-Shaybani's

work is especially instructive. The book is constructed in terms of a series of

judgments, or more properly "opinions" (al-fatawa),

issued by Abu Hanifa, Abu Yusuf, or al-Shaybani. At

one point, for example, the text indicates a question directed to al-Shaybani: "Would a sudden attack at night be

objectionable to you?;' that is, as a tactic in war. The reply, "No harm

in it;' is to be taken as al-Shaybani's response,

reflecting the consensus of the school on this point.18

We get a better sense

of how these scholars worked by attending to a story related by Muslim

historians. Here, Harun aI-Rashid, the Abbasid ruler

in Baghdad from 786 to 809, famous to all readers of the Thousand and One

Nights, calls on several scholars to render an opinion on a vexing question.

Faced with unrest in Iran, Harun sought peace by offering clemency and protection

to a rebel leader. Having accepted Harun's offer, the leader returned to his

province, where he promptly reorganized his forces and resumed his troublesome

activities. Does this subsequent behavior render Harun's promise of clemency

and protection moot?

The question is not

to be taken lightly. Technically, Harun provided the rebel leader with al-aman, a trust or pledge of safe passage. On pragmatic

grounds, it is not good policy for rulers to violate their word; further, the

granting of such a pledge establishes a religious obligation. As the story

proceeds, we find Abu Yusuf and alShaybani arguing

that, having given the pledge, the Abbasid ruler is obligated to treat the

rebel leader in a distinct fashion. He may entreat the leader to cease his

troublesome activities, of course. And if rebel troops violate certain

standards of conduct, the Abbasid fighters may act as a police force quelling a

public disturbance. But Harun ought not to authorize his troops to capture the

leader directly, nor, if the leader is captured in the course of a police

action, is Harun permitted to authorize the summary execution of the man in question.Abu Yusuf and al-Shaybani

do not stand alone in this instance. Other scholars provide Harun with a

different opinion. In this case, the argument is that the grant of al-aman presumed the rebel leader would behave in a certain

way; since he did not, the trust is null and void. Harun is justified in

authorizing his troops to capture the leader, and further in ordering his

execution. In this particular instance, the Abbasid ruler chose the second

opinion. Nevertheless, both Abu Yusuf and al-Shaybani

subsequently served in an official capacity, and Muslim historians remember

their names-not the names of those scholars whose advice pleased Harun

al-Rashid.19

The primary work of

scholars like Abu Yusuf and al-Shaybani, of course,

was teaching. The Hanafi school developed as men like these trained others. As

we read their texts, we see them citing the Qur' an

and reports of the practice of Muhammad and his companions. We also see them

issuing opinions that do not directly invoke these sources, but rather appear

to involve a claim that learned men, devoted to a life of study, can render

trustworthy opinions on matters of right and wrong. Their authority thus rests

on the notion that devotion to learning creates a disposition for justice, or a

leaning toward virtue. Here, it is interesting that the Hanafi school spoke of aI-ray (opinion) and of al-istihsan

(good opinion) as legitimate grounds of judgment. The combination of learning

and piety makes for wise people-not perfect or infallible, of course, but

nevertheless "sound"-and for wise judgment.

We know more about

the Hanafi school than about others, for the obvious reason that scholars like

Abu Yusuf and al-Shaybani had dealings with the

Abbasid court. The existence of the schools associated with al-Awza'i and Malik ibn Anas, as well as the existence of

disagreement among scholars (as, for example, in the story about Harun and the

rebel leader), suggested to some that the Hanafi approach, however exemplary,

did not command universal assent. It is not strange, then, that we find

scholars arguing for a synthesis that would take the best of the various

schools and place Islamic practical reason-that is, Shari'a

reasoning-on a firmer, more systematic theoretical ground. Of these, the most

outstanding was and remains the great al-Shafi'i (d. 820). His works, in

particular al-Risala (The Treatise), on the sources by which one comprehends

the guidance of God, set forth proposals that transformed the practice of Shari'a reasoning.20

Standard histories of

Islamic jurisprudence credit al-Shafi'i with establishing a full-blown theory

of Islamic law. That claim is not quite accurate.21 Al-Shafi'i's real

contribution lies in his insistence that all local or regional traditions, as

well as all scholarly opinions, must be judged with respect to two sources: the

Qur'an, and the sunna, or exemplary practice of the

Prophet. With respect to developments described thus far, this meant, for

example, that the traditions associated with al-Awza'i,

Malik, and Abu Hanifa and his students could not stand on their own. Even

Malik's Muwatta, with its claim to represent a

continuous tradition of practice going back to the earliest Muslims, must be

subjected to review. One can be certain of God's guidance only by referring to

a sound or well documented report of the Prophet's words and/or deeds. The

import of this point becomes clear if we attend to the fullness of al-Shafi'i's

argument. He begins with praise of and petition to God: Praise be to God who

created the heavens and the earth, and made the darkness and the light . . .

Praise be to God to whom gratitude for one of his favors cannot be paid save

through another favor from him, which necessitates that the giver of thanks for

his past favors repay it by a new favor, which in turn makes obligatory upon

him gratitude for it ... I ask him for his guidance: the guidance whereby no

one who takes refuge in it will ever be led astray.22

Al-Shafi'i's petition

for guidance sets the tone for his argument, which is that God provided for

this human need by sending the Prophet Muhammad with a "book sublime:'

With respect to this Book, God "made clear to [human beings] what He

permitted ... and what He prohibited, as He knows best what pertains to their

felicity in this world and in the hereafter."23 Al-Shafi'i stresses that

the guidance offered in the Qur'an is comprehensive and sure: "No

misfortune will ever descend upon any of the followers of God's religion for

which there is no guidance in the Book of God to indicate the right

way."24

According to

al-Shafi'i, the general mode by which God provides guidance may be described as

aI-bayan, a declaration. There are, however, several

categories of declaration, and some of these suggest the necessity of other

sources accompanying or alongside the Qur'an. Thus, one may speak of

declarations "explicit" in the Qur' an, as

in commands that believers pray. One may also speak of declarations tied to

specific Qur' anic texts,

but for which the Prophet's words specify the proper form of obedience. An example

is that prayer should be performed five times a day, and at specific times.

Then, too, there are declarations from the Prophet, establishing duties even

where there exists no specific Qur' ank text. Finally, there are declarations apprehended by

human beings through the use of their capacity for reason, for example in

locating the precise direction of prayer.25

This discussion of

the various types of declaration by which God provides guidance serves to

establish that the quest for the Shari'a, or oath,

involves reference to a set of sources, which must be construed in relation to

one another. Theoretically, the entire world constitutes a "sign;' a

source by which human beings may ascertain God's guidance. More concretely

those in search of guidance refer to texts-to the Qur'an, which as God's speech

constitutes a source "about which there can be no doubt" (2:1); to

reliable reports concerning the exemplary practice of the Prophet; and to

"reasoning" in the sense of interpreting and applying the signs

provided by God in the interests of obedience. In each and all of these

sources, God's declarations are clear. That does not mean, however, that

ascertaining them is simple. To begin, al-Shafi'i says, the Qur'an and reports

of the Prophet's practice are in Arabic. This is not a language everyone knows;

and those who do know it are not equal in their comprehension of its rules. For

some (in effect, many) purposes, reading and interpreting these texts requires

expertise, and there is thus an important role for experts that is, the

"learned"-in ascertaining the guidance of God. al Shafi'i reinforces

this point with reference to a series of distinctions designed to facilitate

interpretation of revealed texts. Some have "general" applicability,

as in "God is the creator of everything, and He is a guardian of

everything" (Qur'an 39:63). Some have "particular" reference;

that is, the declarations are directed toward particular people or contexts, as

in "The people have gathered against you, so be afraid of them"

(Qur'an 3:167). Of course, in some cases declarations with particular

references may take on or contain a general point.26

In some cases, the

meaning is clarified with reference to the sunna, or

exemplary practice, of Muhammad. At this point, al-Shafi'i's unique

contribution becomes clear. As he has it, the Qur' an

contains God's declaration that obedience to God requires obedience to the

Prophet. For God has placed His Apostle [in relation to] His religion, His

commands, and His Book, in the position made clear by Him as a distinguishing

standard of His religion by imposing the duty of obedience to him [the Prophet]

as well as prohibiting disobedience to him.27

For this reason, one

who wishes to identify with Islam must pronounce the shahada (confession of

faith), indicating faith in God and in Muhammad as the messenger of God. As

al-Shafi'i has it, the authority of the Prophet is such that reports of his

words and deeds confirm and explain the guidance contained in the Qur' an. They also extend it, in the sense that a sound

report of the Muhammad's words or deeds may itself establish a duty in cases in

which there is no Qur' anic

text. We have, as it were, two sets of texts with which Shari'a

reasoning must work: the Qur' an, as the Book of God;

and ahadith, reports of the sunna,

or practice, of the Prophet. The latter may interpret the former but will never

contradict it; the former establishes the importance of the latter. To show

this, al-Shafi'i embarks on a long discussion of "the abrogating and the

abrogated;' by which we come to understand that interpretation of the divine

declarations sometimes involves understanding that a text revealed at one time

may be abrogated or rendered null and void by a text revealed at a later point.

For al-Shafi'i, verses of the Qur' an may be

abrogated only by other verses of the Qur'an; while one report of the Prophet's

practice may abrogate another report, it can never be the case that any report

of the words and deeds of Muhammad abrogates any verse of the Qur'an.28 Of

course, such stress on ahadith makes it crucial that

one have a way of distinguishing "sound" reports-those in which one

may have confidence that its text stems from the Prophet himself-from those

which are "weak;' and thus not suitable for use in making judgments. And

if some sound reports abrogate others, one must have a way of relating specific

sayings or deeds of the Prophet to particular times in his career. Al-Shafi'i's

treatise relates some of the basic rules of what one might call "hadith

criticism;' particularly with respect to the problems of judging the

"chain" (al-isnad) by which reports are transmitted. During the next

century several other scholars would devote their skills to this issue, with

the result that six major collections of ahadith came

to be identified as useful in the context of Shari'a

reasoning.29

If all this sounds

very complex, that is because it is so! Al-Shafi'i's text promises that God

provides guidance. The comprehension of guidance involves struggle, however,

and in that struggle, not everyone is equal In particular, those who understand

the language and rules of interpretation pertaining to the signs provided by

God serve as guardians of right and wrong, in the sense of rendering opinions

on the duties incumbent on human beings. The learned are not infallible, of

course. Indeed, the system outlined by al-Shafi'i is made to order for

disagreement. After all, the meaning of God's declarations is not obvious. This

much al-Shafi'i has said, and he reinforces it again and again. As the argument

continues, we learn of the variety of ways by which scholars attempt to extract

guidance from the Qur' an and from the practice of

the Prophet. Some, by which al-Shafi'i means the scholars of the Iraqi school,

rest their opinions on ra'yor istihsan.

Others trumpet the validity of other modes of reasoning. All are engaged in

ijtihad, meaning that they exert "effort" in the attempt to ascertain

the path of God. But the best form of such effort, says al-Shafi'i, is one that

stays as close as possible to God's declarations. This is called al-qiyas, a kind

of reasoning by analogy, in which the texts of the Qur'

an and the sunna are treated as precedents from which

one may draw wisdom. In this connection, the objective of interpretation is to

establish a fit between precedent and current circumstance, by way of identifying

a principle or ground that unites them. As an example, consider al-Shafi'i's

discussion of the duties pertaining to parents and children:

The Book of God and

the sunna of the Prophet indicate that it is the duty

of the father to see to it that his children are suckled and that they are

supported as long as they are young. Since the child is an issue of the father,

the father is under an obligation to provide for the child's support while the

child is unable to do that for himself. So I hold by analogical deduction

[that] when the father becomes incapable of providing for himself by his

earnings, or from what he owns, then it is an obligation on his children to

support him by paying for his expenses and clothing. Since the child is from

the father, the child should not cause the father from whom he comes to lose

anything, just as the child should not lose anything belonging to his children,

because the child is from the father. So the forefathers, even if they are

distant, and the children, even if they are remote descendants, fall into this

category. Thus I hold that by analogy he who is retired and in need should be

supported by him who is rich and still active. 30

The duties of

children to support their elderly parents, and even a more extended duty of

those who are active to support those who are retired, are drawn by way of

analogy from textual precedents requiring parents to care for children. As

al-Shafi'i's text shows, such judgments are not self-evident. Throughout, he

engages the views of others from the learned class. In the end, effort is what

is required; in effect, God requires a conscientious attempt at the

comprehension of guidance. How does one distinguish one opinion from another?

According to al-Shafi'i, one should look for consensus, a convergence of views.

The more extensive the consensus, the more likely that a particular opinion is

in fact correct. Even here, however, disagreement is possible, unless one finds

an opinion on which the entire Muslim community agrees. In that case, the

opinion must be correct, for the Prophet said: "My community will never

agree on an error." Such agreement must have been a rare thing, however;

al-Shafi'i provides no examples.3l

Al-Shafi'i did not

develop his system in a vacuum. That much is already clear, by way of the

relation of his argument to the regional "schools" in which religious

specialists developed their distinctive approaches to the problem of guidance.

But we must fill out the picture with a brief account of the religious policies

of the Abbasid caliphs. The Abbasids came to power in the 740s. In doing so,

they rode the wave of religious criticism of the Umayyads. Promising government

by the Book of God, the new rulers appealed to many in the developing class of

the learned, and through them to popular religious sentiment. In so doing, the

Abbasids obtained a measure of legitimacy. They also pointed to a problematic

that would persist throughout the centuries of their dominance. The problem was

as follows: a slogan like "Government by the Book of God" is

appealing, in part, because it is simple. Followers of Iraqi scholars like Abu

Hanifa understood it, as did everyone else in the 740s. Once in power, however,

the Abbasids found such general appeals of limited use. What mattered, with

respect to actual governance, was the ability of a ruler to command the loyalty

of particular groups, each of which varied in important details. One might, of

course, decide to rule by using a large measure of coercion. The Umayyads had

shown that such a strategy could work, at least for a time. And, from another

point of view, the true problems of governance in the far-flung realm now

controlled by Muslims had to do with economic integration and reform,

especially as these matters affected the competing interests of merchants and

the landed class.

Abbasid rulers

clearly spent a great deal of time on such matters, and they showed themselves

willing to use coercive measures. As Max Weber put it in his studies of

political economy, however, rulers seek legitimacy, at least in part to avoid

the costs of coercive governance. The goal is to rule with authority, meaning

that the subjects of rule believe there are reasons to follow the ruler's

directives other than those associated with fear.32 The Abbasids understood

this psychology, and they sought to ally themselves

with various religious parties, searching for a message of broad appeal.

Indeed, in some cases the search seems to have been not only a matter of

political expediency. The caliph al-Ma'mun, for example, is reported as a man

genuinely interested in the debates of the learned, responsible for (among

other things) the institution of a major translation project by which works

from antiquity were put into Arabic.33

Al-Ma'mun ruled from

813 to 833. His quest for religious allies led him, first, to break with

precedent by appointing someone other than a family member as his successor. In

817 'Ali al-Rida, a man of piety revered by large segments of Muslim society,

agreed to succeed al-Ma'mun as ruler. When al-Rida died the following year,

this particular plan became moot.34 Al-Ma'mun possessed other resources,

however. Thus he turned to some of the scholars associated with the Mu'tazila,

which formed part of the general religious movement during the Abbasid revolt.

Its members practiced a highly distinctive form of religious reasoning called az-kazam, a kind of dialectic argumentation focused on

doctrinal concerns. By the time of al-Ma'mun, members were known for adherence

to five principles: az-tawhid, or unity, stressing

the uniqueness of God in relation to God's creatures; az-

'adz, or justice, in the sense that God is the author of moral law, always does

what is right or best for God's creatures, and requires that human beings use

their freedom to follow in this path; "the promise and the threat;'

meaning that God will enforce the moral law by means of rewards and

punishments, in this world and the next; "commanding right and forbidding

wrong:' in the sense that human beings have a duty to pursue justice; and

"the intermediate position:' indicating the distinctive way the group

approached the religio-political disputes associated

with the early conflicts between 'Ali and Mu'awiya.35

For our purposes, the

Mu'tazili teaching on al-tawhid is the most

important; for it was this principle that led to a highly distinctive and

controversial judgment regarding the Qur'an. When al-Ma'mun's alliance with

members of the group led him to impose a mihna, or

test, upon important members of the learned class, the resulting outcry had

important consequences for the development of Shari'a

reasoning. For the Mu'tazila, al-tawhid meant that God is "incapable of

description" in human terms. In a certain sense, this is a notion shared

by all Muslims. The Qur' an declares: He is God, the

one; God, the eternal, absolute; He does not beget, nor is He begotten; And

there is none like Him. (112)

At the same time, the

Qur'an speaks of God as "all-seeing:' "allknowing:'

"powerful:' "wise" -in effect, attributing to God the kinds of

abilities characteristic of human beings, albeit in superlative quantities. At

2:256 we read: God! There is no god but God, The Living, the self-subsisting,

supporter of all. No slumber can seize Him, nor sleep. To him belong all things

in the heavens and on earth. Who can intercede with Him, except as He permits?

He knows that which is before, and after, and behind his creatures. They shall

not comprehend any aspect of His knowledge, save as he wills. His Throne

extends over the heavens and the earth, and He feels no fatigue in guarding and

preserving them, for He is the Most High, the Supreme.

The image of God here

is as a king-a superlative one, to be sure, mt comparable to those familiar in

human experience. The suggesion is that one trying to

think about God should take human kinghip to the

maximum, and in doing so will begin to understand the lwesome

power of deity. The Mu'tazila feared the possibility of misunderstanding

presented by such anthropocentric language. Their interpretation of al-tawhic, ",as designed to clarify the meaning of the Qur' an, specifically by means of a proposal about the

relationship between human language and the deity of God. Mu'tazili

thinkers insisted that all speech about God was metaphorical. This stricture

applied not only to ordinary speech but even to the "divine speech"

enshrined in the Qur'an. When the sacred text speaks of God's throne extending ove] the heavens and the earth, this is a kind of

accommodation on God': part, employing a vivid image in order to suggest the

sense of awe appropriate to creatures encountering the deity. The "throne

verse; powerful as it is, does not reach to God's "essence;' which

ultimately must be described in negative terms: God is "not finite;'

"has no beginning and no end;' "begets not, and is not

begotten."36

The Mu'tazila spoke

of the Qur' an as "God's created speech:' The'

insisted that the Holy Book provided the best guide with respect to human

attempts to acknowledge and respond to the maker 0 heaven and earth. Yet they

thought it important to signify that eve] this book, "within which there

is no doubt;' and which provide "guidance for the pious;' did not

constitute a mode of direct address There were several reasons for this Mu'tazili version of al-tawhid. Not least was their worry

that popular modes of interpretation might elide the distinctions between

Islamic and Christian representations of deity. As Muslims understood it, the

practice by which Christians referred to Jesus of Nazareth as "son of

God" confused the creature with the Creator. If popular piety presented

God as sitting on an actual, albeit heavenly, throne, or as actually seeing (by

means of some superlative capacity of vision), how much difference would remain

between Muslims and their Christian subjects?38

And there is in

fact evidence that Muslims did speak in ways that suggested the kind of

embodied God who might be able to sit on a throne, watch over humanity, and so

on. Popular creeds promised that the blessed would "behold the face of God"

in paradise. In doing so, the creeds rested on the notion that the Qur'an, as

God's speech, is God's self-description. For many reciting the creeds, the

pages of the Qur' an might be created, as were the

ink and the voice of the reader. But the speech is God's speech. One who hears

the Qur'an recited or reads with comprehension does not simply encounter

notions of deity. Such a person is in the presence of nothing less than the

living God. Under Mu'tazili tutelage, al-Ma'mun

determined to institute a test by which the learned would testify to their

adherence to the doctrine of God's created speech. According to standard

accounts, the test focused on well-known scholars in and around the capital.

The same accounts insist that most of those subjected to the test swore their

allegiance to the Mu'tazili doctrine of the Qur'an.

It seemed that al- Ma 'mun was well on his way to ensuring a uniform notion of

orthodox practice, which would certainly serve well in the Abbasid quest to

secure religious support. The main (and, in some accounts, the sole) holdout

among the learned was Ahmad ibn Hanbal (d. 855).39

Ahmad was a scholar

of ahadith; that is, he specialized in collecting

reports about Muhamad's words and deeds, and in searching these out so as to

ascertain hose that were sound.40 The connection between Ahmad's scholar;hip and the work of al-Shafi'i is striking. Not

that they agreed on all Joints; however, Ahmad shared with al-Shafi'i the idea

that the dirine path was best comprehended by a

faithful reading of the precedents established in the Qur'

an and the sunna. It is significant that much of the

substance of popular piety involved appeals to the Prophet's words and deeds.

Thus, the notion that the blessed will see 30d's face rests not on the Qur'an,

but on reports from the Prophet. Similarly, stories of God shaping the human

creature out of clay and Jreathing life into it are

prophetic extensions or elaborations of verses in the Qur'

an. Perhaps most important, sayings attributed to the Prophet tie the Qur' an and other scriptural texts to a heavenly book,

specifically characterizing the Qur' an as an Arabic

version of the divine speech enshrined in this "mother of books."

Accounts of the mihna thus present Ahmad ibn Hanbal as the champion of the

kind of popular piety associated with ahadith. He was

an adherent of the sunna of the Prophet who did not

substitute his own theory of religious language for the Prophet's

characterization of the Holy Book. And, true to this image, Ahmad did not swear

allegiance to Mu'tazili doctrine. Rather, he insisted

that he would not answer, because the caliph lacked competence to put the

question. It is important to note the technical and reserved way in which Ahmad

ibn Hanbal resisted the mihna. Traditional accounts

do suggest that his differences with al-Ma'mun and thus with the Mu'tazila were

substantive. For Ahmad, faithfulness required staying within the language of

revealed texts. One might qualify the throne verse by saying something to the

effect that God's throne is unlike any present to ordinary experience. One

would not, however, speak of the depiction as metaphorical; the verse is God's

self-description. Nevertheless, Ahmad's resistance to the test was technical.

Claiming that the authority of the caliph rested on adherence to the Shari'a, he noted that there was no text in the Qur' an or in sound reports of the prophetic sunna on which to base the claim that the Qur' an was "created"

speech. Where there was no text, there could be no binding judgment; where

there was no binding judgment, there could be no obligation; where there was no

obligation, there was no right or duty of the ruler to. demand obedience. With

respect to the question at hand, the caliph had no right to restrict the

conscience of a Muslim. Al-Ma'mun had overstepped his bounds.

Answering the

caliph's summons, Ahmad appeared at court. By this time, al-Mu'tasim (833-847)

held the office, al-Ma'mun having died. Having been flogged and imprisoned by

order of the ruler, Ahmad presented a careful justification for resistance. A

Muslim, he said, is obligated to honor the ruler, and to obey all lawful

orders. Faced with an unjust command, the same Muslim is obligated to refuse

obedience. According to Ahmad, such refusal ought not to be confused with a

right to revolt. Ahmad seems to have been one of those scholars who held that

revolution is never (or almost never) justified. Rather, the refusal of an

unjust command should be construed as "omitting to obey." Ahmad's

resistance to the mihna thus provides a fascinating

instance of political behavior. On the basis of the stories of the mihna and of Ahmad's continuing refusal of association with

the Abbasids, even after the caliph al-Mutawakkil (847861) succeeded to power

and reversed al-Ma'mun's order, Michael Cook speaks of Ahmad's "apolitical

politics."41 By this, Cook means to capture the political relevance of a

life devoted to religious testimony, inclusive of a refusal of any and all directassociations with governing institutions.

One could say more

about this episode in Islamic history. However, the point with respect to our

interests has to do with Ahmad ibn Hanbal as an exemplar of developing trends

in the practice of Shari'a reasoning. Devotion to the

Prophet and, with it, the interest of the learned in identifying sound reports

of the prophetic sunna had tremendous implications

for the development of Shari'a reasoning. Al-Shafi'i

and Ahmad ibn Hanbal are two of the most important figures in this development.

Indeed, Ahmad would be remembered as much for his collection of prophetic

reports as for his various responses to questions, even as al-Shafi'i would be

remembered for his systematic statement defining the Qur'

an and the prophetic sunna as primary sources for

comprehending the Shari'a.

By the eleventh and

twelfth centuries, the system toward which alShafi'i

and Ahmad ibn Hanbal pointed was firmly in place, with scholars like al-Mawardi (d. 1058), al-Sarakhsi

(d. 1096 or 1101), Ibn 'Aqil (d. 1119), and Ibn Rushd (d. 1198) as exemplary

practitioners. Their goal, via Shari'a reasoning, was

comprehension of the divine path. To this end, they worked with usul al-fiqh, the sources of

comprehension, meaning a system of agreed-upon texts and rules of

interpretation by which the learned might craft al-fatawa,

opinions or responses to questions raised by the faithful, and thus facilitate

the Muslim community's fulfillment of its mission, namely, commanding right and

forbidding wrong, for the good of all humankind.

As an example,

consider the brief account given in Ibn Rushd's prefatory remarks to Bidayat

al-Mujtahid, a book intended to aid in the training of the special class of the

learned trained in al-fiqh, or comprehension, of the

Shari'a.42 Ibn Rushd's work is a compilation of the opinions of the learned on

a variety of questions. The opinions gathered on these questions show the ways

in which the learned work with texts (the Qur'an and the sunna)

in order to judge cases. In some cases, judgments are based on explicit texts.

There may nevertheless be important issues of interpretation, such as those

related to whether a given prescription is general or particular. Thus, when

the Qur'an (at 9:103) orders the Prophet to "take zakat [alms] of their

[believers'] mal [wealth], wherewith you may purify them and may make them

grow;' it is important to know that the word mal applies only to certain kinds

of holdings. Or again, when Qur' an 17:23 orders

"Do not say 'fie' unto them nor repulse them, but speak to them a gracious

word;' it is important to understand that the prohibition is not only of one

specific kind of act, but of all sorts of rude or antisocial behavior:

"beating, abuse, and whatever is more griev 43

Similarly, it is

important to know the type of prescription or prohibition implied by a

particular text. Some judgments indicate that a particular act is

"obligatory;' as in the order to establish right worship by praying five

times daily. Others are recommended, as in acts of worship above and beyond

such required prayers. Still others are forbidden, as in the command against

eating carrion. Others are "reprehensible;' in that they make it easier

for one to perform forbidden acts. Finally, some judgments indicate that a

particular act is "permissible"; that is, there is choice with

respect to its commission or omission. In each case, it is critical to know not

only how to classify an act, but also how it applies to particular agents.

Thus, some acts are "communal" obligations; that is, so long as some

perform them, others may be excused. Others, by contrast, are

"individual" obligations, which no one can perform for anyone else.

Fighting in war, at least in most circumstances, provides an example of a

communal obligation. Praying five times a day provides an example of individual

duty.

In ascertaining the

type of judgment enshrined in the Qur' an and the sunna, some opinions are clear, in the sense that there is

no dispute about them, while others must be described as "probable:' The

latter are within a range of acceptable interpretations, and thus reasonable or

conscientious disagreement is tolerated. There are cases, however, for which

there is no clear text. With respect to these, a scholar must exert his reason.

The preferred mode for such effort is al-qiyas, or analogy, already mentioned

in our discussion of al-Shafi'i's work. As Ibn Rushd puts it, legitimate

"analogy is the assigning of the obligatory judgment for a thing to

another thing, about which the Shari'a is silent,

[because of] its resemblance to the thing for which the Shari'a

has obligated the judgment or [because of] a common underlying cause between

them:'44 In some cases, the analogy between a judgment enshrined in the Qur'an

and the sunna is established through a kind of

similitude (al-shabah) of cases; in others, by an

appeal to a common principle (al- 'illa) that joins

them. As Ibn Rushd has it, the differences between these are subtle, and they

often lead to disagreement. With respect to such differences, one may often be

instructed by the consensual judgment of the learned, which suggests that a

given judgment (attained by reasoning) is "considered definitive [because

of] predominant probability."45 But the fact that such consensus (al-

'ijma) rests on interpretations of the Qur' an and

the sunna always leaves open the possibility that a

specific judgment might be overturned or overridden as a result of new

information, difference of circumstance, and the like. Thus Ibn Rushd

establishes the notion that independent judgment-that is, the promulgation of a

learned opinion that overturns a precedent established in the judgment of

earlier generations of scholars-always remains a possibility. Wael Hallaq

characterizes the work of Ibn Rushd and other 'ulama of the eleventh and

twelfth centuries as a kind of "golden age" of Shari'a

reasoning among Sunni Muslims. The terminology of Sunni and Shi'i is not

particularly useful for the very early period of Islamic history. It is

relevant at this point, however, and thus it is useful to think of a comparable

golden age among Shi'i scholars, either in connection with the work of noteworthies like al- Mufid (d. 1023) and his students

Sharif al-Murtada (d. 1044) and Muhammad ibn al- Hasan al- Tusi (d. 1068) in

eleventh -century Baghdad, or in connection with the school of aI-Hilla, a town located between Kufa and Baghdad, in the

thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.46 As the locations suggest, a

distinctively Shi'i approach to Shari'a reasoning

grew up in the southern and eastern portions of Iraq; Iran also became an

important center. Both Baghdad and Hilla scholars may be associated with the Ithna ash'ari, or Twelver,

version of Shi'ism, meaning that they accepted the notion that after the death

of Muhammad, leadership of the umma passed to 'Ali as his designated successor,

and then to a series of others, up to the twelfth imam, Muhammad, son of Hasan

al-Askari.’ As the Shi'a had it, the infant Muhammad was taken into hiding by

the will and purpose of God in 873/874, where he will remain until the day of

God's decision. At that point the hidden imam will appear as al-Mahdi, the

rightly guided one, who will lead the faithful in establishing the reign of

justice and equity, and will rule over humanity for a thousand years.

From the Shi'i point

of view, the events of the first fitna thus

constituted a rejection of the Prophet's plan for his community, and further

created a context in which the majority of Muslims were prevented from

following the straight path associated with alshari'a.

This rejection, confirmed in the subsequent careers of 'Ali's sons and their

successors, meant that important parts of the enterprise of Shari'a

reasoning were to be viewed with suspicion. In particular, the use of reports

of the Prophet's sunna needed critical scrutiny, so

as to ascertain when and where persons involved in the rejection of 'Ali's

leadership might have altered or even fabricated these important texts.

The work of Shi'i

'ulama thus presupposed an alternative to the great collections of ahadith utilized by Sunni scholars. In this regard, the

Shi'a drew on tenth-century works by collectors like al-Kulayni

(d. 941/942) and Ibn Babuya (d. 991), each of whom

focused on the isnad, or chain, of transmitters attached to a specific report.

Reports were judged "sound;' and thus useful for the normative purposes of

Shari'a reasoning, only in cases in which the chain

was secured through the inclusion of the name of one of the designated imams or

leaders, or of the names of people whose trustworthiness was established by the

leaders' testimony.48

Interestingly,

certain of the reports approved in Shi'i collections testify to the authority

of "reason" (al- 'aql) in the affairs of

humanity. These reports correlate with the general tendency of Twelver 'ulama

to affirm al- 'aql as one of the sources of Shari'a reasoning. The precise import of this

affirmation-that is, in what way it serves to distinguish Shi'i from Sunni

versions of the practice of Shari'a reasoning-is a

matter of some debate. We might note the way in which Shi'i scholarship and

piety delighted in stories whereby the learned find consensus on a certain

matter, only to have one dissenter rise and prove the consensus wrong-in which

case "consensus" is the error of the majority, and "right

reason" the mode by which the dissenter makes the case. Such stories

fostered a culture in which the learned considered themselves more independent,

and thus more willing to revise precedent than in the Sunni case.49 At the same

time, the development of the Shi'i approach to Shari'a

reasoning indicates that the Twelver 'ulama were not always clear about the

extent to which reason should be viewed as an independent source of judgment.

In the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century debates between usulis,

advocates of reason, and akhbari, advocates of

textual precedent, Twelver 'ulama engaged in complicated disputes regarding

this question. While all parties asserted that, in principle, a sound judgment

is in accord with right reason, it was not-some would say, still is not clear

just how this claim works in relation to specific cases. 50

The judgments

scholars in the eleventh and twelfth centuries reached about specific

questions-for example, "When may the ruler of the Muslims authorize

military force?" or "What tactics are acceptable in the conduct of

war?" -served as precedents to which subsequent generations of scholars

would recur.

In either case-that

is, whether one is speaking about the framework of Shari'a

reasoning or about judgments pertaining to specific questions of right and

wrong-the practice of Shari'a reasoning involved a

balance between continuity and creativity. With respect to continuity, the

accomplishments of earlier generations demanded respect. A scholar working in

the fourteenth century, as did Ibn Taymiyya (d.

1328), styled himself a follower of Ahmad ibn Hanbal and his disciples,

referred to his predecessors as guides and teachers, and clearly thought that

in some sense they were his betters. Similarly, al-Wansharisi

(d. 1508) expressed his particular debt to Malik ibn Anas and his followers,

and in his opinions showed particular deference to their approaches and

judgments. In this emphasis on continuity with the past, Ibn Taymiyya and al- Wansharisi were

typical. Scholars learned the craft of Shari'a

reasoning at one or another center of Islamic learning-Damascus, Baghdad,

Cairo, the holy cities-in terms of the practice of one of several madahib, schools, or, perhaps more accurately, trajectories

of interpretation. Having mastered a set curriculum, a scholar received a

certificate signifying qualification to advise believers regarding the Shari'a in a manner appropriate to his level of attainment.

For most, this meant practicing al-taqlid, or imitation, meaning a

qualification to repeat the consensual judgment of scholars associated with a

particular trajectory of interpretation. For others, it meant practicing al-taqlid

with a wider range; these were qualified to repeat the consensual judgments .f

each of the four standard schools, and to engage in comparison nd contrast so that those seeking advice might select the

judgment hat seemed best, or most advantageous.

For a few,

however-scholars like Ibn Taymiyya and altVansharisi-training in Shari'a

reasoning provided a platform by I'hich to engage in

independent judgment. Here, the ability to crete

might rest on fresh insight into the sources and framework of ;hari'a reasoning. As noted in the discussion of Ibn Rushd's

sumnary of the theory of sources, analogical

reasoning could be the ource of much disagreement.

Ibn Taymiyya understood this, and he lrgued that many of his predecessors leaned on this

overmuch in heir attempts to distinguish right from

wrong. Appealing to the exlmple of Ahmad ibn Hanbal,

Ibn Taymiyya held that a direct appeal o al-maslaha, "that which is

salutary with respect to public interest;' n many cases constituted a more

honest and better approach, not east because it did

not attempt to force connections between textual )recedents

and contemporary judgment. At other times, the ability to create rested on an

understanding hat distinctive circumstances call for

new judgments. Thus, when u-Wansharisi dealt with the

question "Are Muslims living under a lon-Islamic

government required to emigrate to the realm of Isam?" he argued that the

proper answer would be yes, despite the fact hat the

consensual precedent of several generations suggested the opposite. In doing

so, al- Wansharisi appealed to the special circum,tances created by the Spanish reconquista,

and argued that these constituted a renewed threat, not only to the security of

Muslims livng in this formerly Islamic territory but

to the rest of Islamic civilizations1 Muslims who continued to reside in Spain

constituted a security risk, in the sense that their lives and property might

be seized 'y the new regime and utilized to extort territorial or other conces:ions from the Muslim ruler.

Thus, new times or

new insights might yield new approaches or judgments. Nevertheless, Shari'a reasoning is properly characterized as a

conservative practice, in the sense that it requires that most participants

follow the line of precedent. True creativity, in the sense of establishing new

or further precedent, is reserved for the few. When those few claim the right

of independent judgment, their claims are likely to be controversial. It is not

surprising, then, that the history of Shari'a

reasoning is a history of conflict, in which argument is often connected with

violence. That Ibn Taymiyya spent much of his life,

and wrote most of his books, in the prison of the Mamluk ruler in Cairo, is

instructive. Similarly instructive are the careers of several figures who stand

out as early respondents to the great changes that began to affect Muslim

societies in the mid to late eighteenth centuries. The first, Shah WaliAllah of Delhi (1703-1762), was the most eminent member

of the learned class working during the closing decades of Mughal rule.52

Beginning in the sixteenth century with Babur (d. 1530), the Mughal rulers

asserted Islamic dominance in India. By the time of Wali Allah's birth, the

power of the Muslims was fading, and Aurangzeb (d. 1707) was the last great

Mughal ruler in the Indian subcontinent. Muslim scholars like Wali Allah hoped

to revivify Islamic power through renewed attention to the practice of Shari'a reasoning. To that end, he established a new center

for the training of young scholars, whose job it would be to call the Muslims

of India to fulfill their vocation of exercising leadership by commanding right

and forbidding wrong.

The project would

prove difficult, however, not least because of the gradual yet seemingly

irresistible growth of British power. One of the sons of Wali Allah would deem

it necessary to declare in 1820 that India should no longer be regarded as

Islamic territory. In part, 'Abd al- 'Aziz's fatwa, or opinion, reflected

intra-Muslim polemics. In solidifying their power, the British turned first to

Shi'i Muslims, who were concentrated in the north; Abd al- Aziz and other Sunni

culama regarded this recognition of the Shica as an establishment of heresy.

At the same time, the

1820 ruling reflected a more basic reality: whether working through the Shica or through the Hindus, the British were not dedicated

to the Sharica. From cAbd al- cAziz's

perspective, British rule meant a non-Islamic establishment, in which the

ability of the Muslim community to carry out its historical mission would

necessarily be limited. For Islam to flourish, there should be a political

entity dedicated to rule by the Sharica. A Muslim ruler or a group of Muslim

rulers should plan and carry out policy, in consultation with the learned

class. And in such a context, the flourishing of Islam would redound to the

benefit of all those governed, and indeed of all humanity-even, or perhaps

especially, those members of the protected Jewish and Christian-or, more

importantly in India, Hindu and Parsee (Zoroastrian)-communities. While Abd al-

Aziz did not declare that the new situation required armed resistance, his

opinion did suggest the need for struggle aimed at change. The participation of

Muslims in the 1857 rebellion known as the Sepoy Mutiny summons echoes of the

opinion of cAbd al- cAziz.

And when a number of the learned responded to this failed rebellion by founding

a new center of Islamic Studies in Deoband in 1867, the spiritual and physical

descendants ofWali Allah and cAbd

al- cAziz were important participants. 53 Today their

influence is most clearly felt in the activities of two quite distinctive

groups: the Tablighi JamaCat, which aims at revival

of Islamic influence through the cultivation of spirituality among Muslims; and

the Taliban, best known for their brief but noteworthy period of governance in

Afghanistan between 1990 and 2001.54

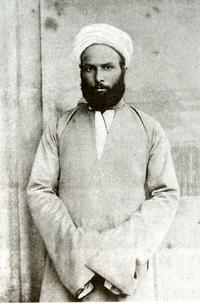

A second figure

illustrating the early modern course of Sharica reasoning is Muhammad ibn cabd al-Wahhab (1703-1791), the founder of the Wahhabi

movement.55 cAbd al-Wahhab's legacy in Saudi Arabia

and, through Saudi missions, throughout the world is pervasive. His career

began in relative modesty, however. In the eighteenth century, the Arabian

Peninsula was regarded as a backwater by the rulers of the Ottoman state.

Perhaps, though, the very distance between economic and cultural centers like

Istanbul, Damascus, and Baghdad provided space for a reformer like 'Abd al-

Wahhab. In any event, he and his colleagues began to issue Shari'a

opinions condemning much of the religious practice of those living in the historicalland of Muhammad. In 1746 the group of scholars

formed an alliance with the family of al-Sa'ud,

adding political and military force to their campaign against jahiliyya. As the Wahhabi-Saudi leadership understood it,

the combination of "calling" Muslims to repentance and punishing

(fighting) anyone who refused the invitation was consistent with the Shari'a vision of Muslim responsibility. Commanding right

and forbidding wrong through the establishment of an Islamic state was the key

in carrying out the mission of Islam.

For a third set of

developments in the early modern period, we turn to Iran, where Shi'i scholars

found it necessary to issue opinions urging the Qajar rulers to use military

force in order to resist Russian incursions into Iranian territory. In doing so,

the Twelver 'ulama presented themselves as guardians of the Shi'i (and thus,

from their point of view, the Islamic) character of the Iranian state. While

not without precedent in the premodern practice of Shi'i scholars, such

judgments did move the 'ulama in the direction of an activism that would

enhance their authority as leaders of a resistance intended to safeguard the

territory of Islam against foreign intruders.56

Shari'a reasoning is best regarded as an open practice, in

that readings of its sources with a view toward discerning divine guidance in

particular contexts can yield disagreement. So it is not surprising that the

course of Shari'a reasoning from the 1700s to the

present is characterized by vigorous (and not always irenic) argument. Thus,

even as some of those inheriting Wali Allah's mantle took Shari'a

precedents to suggest a duty of armed resistance to British rule in India,

others suggested that the new context led in a different direction. Similarly,

even as the Wahhabi scholars allied themselves with the Saudi clan in a

movement that would issue in the founding of a new state, or as the Shi'i

'ulama urged resistance to foreign influence in Iran, their judgments were

subjected to criticism. For now, let us focus on India, where the scholars of

Deoband could support the pietistic revival of the Tablighi Jama'at,

as well as the political and military campaign of the Taliban. Even more

distinct was the program of educational reform advocated by Sayyid Ahmad Khan.

Declaring that armed struggle cannot be required in the face of superior force,

Sayyid Ahmad cited Qur'an 13:11 (God "never changes the condition of a

people until they change themselves") in support of a program of modern

scientific and technical as well as traditional learning. By this means, he

argued, the historical stature of the Muslim community might be restored, for

those who control scientific and technical knowledge hold the keys to political

influence. And political influence, in turn, would create a space for Muslims

to command right and forbid wrong. 57

Sayyid Ahmad's

program of reform provided the inspiration for a new center of learning,

Aligarh Muslim University, which came to represent a kind of

"modernist" or "reformist" approach to the new situation of

Muslims. Whereas Deoband maintained a more or less traditional approach,

particularly with respect to the training of religious specialists, Aligarh

Muslim University sought to train a new type of Muslim leader: a

"lay" person, literate in the sources of Shari'a

reasoning, but also trained in the kinds of scientific and technical learning

that Sayyid Ahmad saw as the root of British power. But although both

institutions could be described as "Shari'a

minded;' in the sense of advocating a particular role for the Muslim community,

connected with its historical mission of religious and moral leadership, Sayyid

Ahmad's university came under serious criticism from those who thought they

discerned in its program an overly cooperative, even conciliatory, approach to

British rule. In particular, Jamal al-Din, known as aI-Afghani

(1839-1897), mounted a vigorous critique of Sayyid Ahmad, arguing that the

first task before the Muslims was to free themselves from British dominance.

Only afterward would it make sense for Muslims to determine the course of

reform most appropriate for carrying out their mission in the modern world.

AI-Afghani advocated extensive reform.58

From his perspective,

the traditionalism represented by Deoband was inadequate to the condition of

Muslims in the nineteenth century. Muslims must first comprehend the nature and

scope of the change affecting the Indian subcontinent, and indeed the whole of

the realm of Islam. AIAfghani thought the change

could be described only as a catastrophe. Moving from India to Turkey to Egypt

to Iran, this mysterious and charismatic personality carried a message of

reform based on a return to authentic Islamic sources. For al-Afghani, however,

such return could not simply be a matter of reading and rereading precedents

set in other generations. To cope with their loss of power, Muslims needed to

recover a sense of the openness of the Shari'a

vision, particularly with respect to scientific and technical learning. Quoting

the Prophet, "Seek knowledge, wherever you may find it;' aI-Afghani argued that true religion-true Islam-supports

scientific inquiry, and that a community practicing true religion-again, true

Islam-would find itself, as a matter of course, fostering scientific and

technical expertise. Noting that Christian scriptures are filled with such

otherworldly sentiments as Jesus' or Paul's suggestions that poverty or

celibacy might be of greater value than the creation of wealth or the building

and maintenance of families represented in marriage, aI-Afghani

argued that Europeans had obtained scientific and technical prowess only by the

abandonment of faith represented by the Enlightenment. By contrast, Muslims lost

such prowess as a result of their lack of piety, and recovery of piety would go

hand in glove with recovery of scientific power.

The first order of

the day, however, should be the reassertion of the political vision associated

with Shari'a reasoning. Given that Muslims were

called to lead humanity, al-Afghani argued, how could they accept the dominance

of Great Britain, of France, or of Russia, particularly in the territories

historically associated with Islamic rule?

Al-Afghani's legacy transcended a career marked by recurrent failures.

His encounter with Ahmad Khan occurred during a sojourn in India in 1879 after time

spent in Afghanistan, Turkey, and Egypt. In every case, his personal charisma

proved sufficient to secure him access to circles of power, seemingly with

great ease. But his outspokenness proved equally sufficient to ensure that no

circle of power could long abide al-Afghani's presence. By the early 1880s he

was living in Paris, where he wrote several influential works, in particular a

response to Ernst Renan's portrayal of an inevitable rivalry between science

and religion. In the early 1890s al-Afghani reemerged as a player in the

Iranian resistance to British rule, even traveling to Russia in order to