By Eric Vandenbroeck

Bankrupting The Enemy

While previously we mentioned that Japanese textbooks

generally referred to a U.S. financial siege of Japan "before" Pearl Harbor,

US documents released in the context of the Holocaust Era Records Act between 8

and 10 years ago show among others that from 1937 to 1940 a dozen experts in

U.S. financial agencies analyzed Japan's balance of payments, gold production

and reserves, scrap gold collection, liquidation of foreign investments, and

other financial data. They also predicted when Japan would be bankrupt and have

to stop the war in China, always six to eighteen months in the future. It was a

comforting thought to policy makers, but the analyses were wrong. From

1938 to the summer of 1940 the Bank of Japan secretly accumulated $160 million

in the New York agency of the Yokohama Specie Bank. It began with funds removed

from London. It was a sum equal to three years' of oil purchases from the U.S.

The YSB did not report the deposits, as required by law. Bank examiners

discovered the fraud in August 1940. Japan raced to withdraw the money during

the first half of 1941. The fraud accelerated thinking in Washington toward a

dollar freeze, instead of commodity embargos, as the most deadly sanction. The

freeze order was drafted in March 1941. As is well known, It was imposed on 26

July 1941 when Japan occupied southern Indochina. After the freeze, Japanese

diplomats and agents proposed many ideas to unfreeze dollars in order to reopen

trade. Dean Acheson, the effective manager of the freeze policy, rejected them

all. In August 1941 the Japanese government, through Mitsui, made an

extraordinary offer to barter $60 million of silk for $60 million of US

commodities, mainly oil. Barter would not require unfreezing dollars, they

thought. Strangely, they chose as spokesman a Roosevelt-hating

lawyer named Raoul Desvernine.

Acheson and Vice President Wallace rejected the scheme on 15 September, about

the time the Japanese government was deciding for war. Furthermore features of

the prewar situation from records that were not classified but that are omitted

from other history books, thus there are a large number of vulnerability

studies, of Japan's foreign trade written in April 1941 by committees of trade

experts of U.S. agencies under direction of the Export Control Administration.

Reviewing the oil and tanker situation in both Japan and the U.S. for example

one will here find that FDR blamed an imaginary shortage of gasoline in America

as a reason for the freeze of Japan. There was no shortage despite the loan of

20% of US tankers to Britain. Two-thirds of Japan's dollar earnings were due to

exports of raw silk to America. (When war began in Europe all other currencies

became blocked and inconvertible.) The Great Depression and rayon substitution

destroyed the silk dress industry. After 1930 nearly all Japan's silk went for American

women's stockings, which was a strong market despite the Depression. On 15 May

1939, however, DuPont introduced nylon stockings at the New York Worlds Fair. They were a great success. By 1941 nylons

gained 30% of the market, and were on track to 100% in 1943 if no war. The

market loss of $100 million per year would have been a disaster for Japan if it

had not gone to war. Yet what the following case study furthermore shows is

that Roosevelt's idea of a financial siege of Japan in fact backfired by exacerbating

rather than defusing Japan's aggression. And for sure the attack on Pearl

Harbor was not the result of a deliberate Roosevelt strategy (as right-wing

conspiracy theorists claim), but a Roosevelt miscalculation.

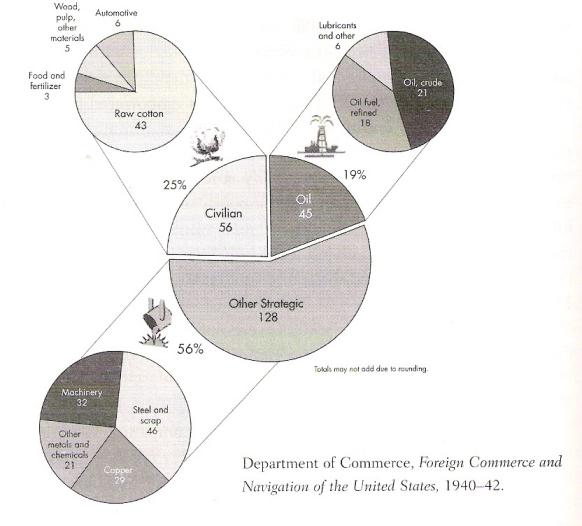

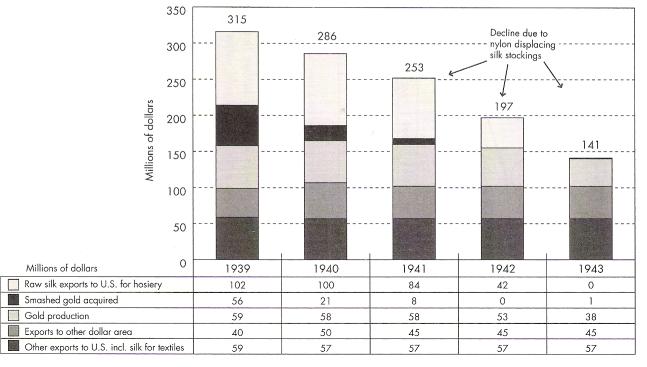

U.S.Exports to Japan 1939 (in Millions of Dollars)

U.S.Exports to Japan 1940 (in Millions of Dollars)

U.S.Exports to Japan 1941 (in Millions of Dollars)

The American

perception of Japan's economic and financial vulnerability dated back to a time

thirty-five years before Pearl Harbor. President Theodore Roosevelt grew

concerned after the victory over Russia in 1905 that Japan would seek to

dominate China in contravention of the U.S. Open Door policy, which championed

independence and free trade for China. Japan would perceive that policy, and

U.S. bases in the Philippines and Hawaii, as barriers to building an empire.

Roosevelt asked the U.S. Navy for a plan to fight Japan, if and when necessary.

The result, War Plan Orange, was fundamentally an economic strategy in both

origins and outcome. (Japan was code-named Orange, the United States Blue.) The

godfathers of the plan, Admirals George Dewey and Alfred Thayer Mahan, had

served as young officers enforcing the Union's Anaconda Plan against the

Confederacy, an "island" vulnerable to economic blockade. They and

later disciples in the War Plans Division of the Navy demonstrated a fierce

mindset favoring vigorous action, a mindset echoed by civilian bureaucrats who

advocated a nonviolent economic and financial "war" against Japan in

the crisis years before Pearl Harbor.

While U.S. military

planners assumed Japan's war aims would be limited --a surprise attack, victory

in naval battle, and a negotiated peace ceding dominance of East Asia--their

aim was a crushing defeat of the enemy, an aim demanded by an aroused public.

They understood that Japan, an island nation poor in natural resources,

depended on overseas trade for the sinews of war and its very economic life.

The Japanese Empire produced food enough, but industrialization and conquests

led to voracious needs of metals and fuels. The planners designed a strategy of

siege. After initial losses, Blue forces would fight back island by island,

sink the enemy fleet, seize bases near Japan, starve it of vital imports, and

ultimately force it to capitulate. Japan's financial destitution would be

ensured by "coercive pressure" on world lenders to deny funds such as

Wall Street provided during the Russo-Japanese War. Plans rang with confidence

that the United States could enforce "final and complete commercial

isolation" (1906), leading to "eventual impoverishment and

exhaustion" (1911) and "in the end ... economic ruin" (1920). As

air power came of age, bombing of industry and transportation intensified the

siege plan. In 1941 Plan Orange morphed into global Plan Rainbow Five, and in

1942-45 it was executed in most major respects. The Pacific war culminated in

unconditional surrender after devastation of Japan's economy, including, at the

end, the deployment of atomic bombs.

In the 1930s

peaceable internationalist governments in Tokyo gave way to military-dominated

regimes. The anticipated violations of the Open Door unfolded in the invasion

of China and designs against colonies of the Western powers. The helplessness

of Japan, if isolated economically and financially, evolved into an axiom at a

time when the U.S. government was averse to fighting a war. When national

policy to deter Japanese aggression took root, the United States gradually

deployed its vast economic and financial powers to strangle Japan by means

other than ships and bombs. It was a Plan Orange strategy in peacetime. The

story now turns to the U.S. strategy of achieving the nation's foreign policy

aims, without combat, by bankrupting Japan.

When Japan invaded

China on 7 July 1937, U.S. government financial experts reckoned the aggressor

could not wage a long war because it lacked hard currency to purchase essential

commodities abroad. As Herbert Feis, the economic adviser of the State Department,

wrote, "Warfare requires many vital raw materials which Japan does not

possess at all or in sufficient quantities, and which must by

purchased with foreign exchange." Therefore, the "ability of Japan to

carry on a protracted war depends ultimately upon her actual and potential

foreign exchange resources." 1

And as early as 1935,

it sought to regulate its position as the world's most important supplier of

materials for war, it was in the summer of 1941 the United States decided to

deploy its most powerful economic sanction against Japan, dollar freezing. The

first steps, taken at a time when Japan was not yet an aggressor in China, were

aimed at keeping the United States from being drawn into another foreign war.

Later steps were taken by so-called voluntary means and by executive orders to

ensure that the nation's exports did not support Japanese aggression in China.

In fact sanctioning to impose a nation's will on others in peacetime was also,

not a novel concept, as it was based on international law governing trade

relations among sovereign states laid down by the European jurists Hugo Grotius

and Emeric de Vattel in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Thus in the autumn of

1937 Franklin Delano Roosevelt brooded about deterring foreign military

dictatorships from attacking peaceful nations. On 5 October, thirteen weeks

after Japan invaded China, the president delivered his famous

"quarantine" speech. Likening the spreading aggressions to an

epidemic disease, he suggested that law-abiding countries ought to quarantine

the aggressors. When pressed by reporters, he denied that he meant economic

sanctions, calling sanctions "a terrible word to use." "There are,"

he said, "a lot of methods in the world that have never been tried

yet."! Roosevelt was not sure what he meant until December, after Japanese

bombers sank a U.S. gunboat in China. He turned to his energetic secretary of

the treasury, Henry Morgenthau Jr., for a "modern" weapon to wield

against Japan. Treasury experts unearthed the perfect device: a relic of the

First World War known as Section 5(b) of the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA),

a single paragraph that empowered the president to paralyze dollars owned by

foreign countries, whether enemy or not. Denial of U.S. dollars, a key reserve

currency of the world and indispensable to Japan for waging war, could dissuade

Japan from belligerence. That surviving section of the act had arisen from an

obscure spat in 1917 between government agencies that foreshadowed the

bureaucratic grasping for power in Washington during 1937-41 as the United

States groped toward invoking its great financial powers to render Japan

effectively bankrupt in the world.

And finally the first

months of 1941 then, marked a turning point in the will of the United States to

advance from a patchwork of export restrictions to full-blooded financial

warfare against Japan. A spurt of work from January through March established the

nature of the financial punishment it would mete out when the time came. Above

all, that the levers of control would be manipulated not by learned economists

and banking technicians, nor by moderate diplomats seeking bargaining leverage,

but by truculent lawyers determined to show Japan no mercy.

In common English

usage, "bankruptcy" is a synonym for "impoverishment."

Japan was cast into international bankruptcy, a condition of absolute

illiquidity, by the U.S. financial weapon. The choke hold of the relentless

freeze rendered its dollars and gold worthless for national survival. It was a

strange sort of bankruptcy. Japan's reserve of gold and dollars exceeded $200

million in late 1941, enough to buy, for example, four years of U.S. oil at

pre-freeze shipment rates, yet it was rendered useless. Thereafter Japan piled

$60 million of new gold and $15 million of silver into the useless reserve

every year until it suspended mining of precious metals in 1944. Japan had

invested in gold mines, collected gold ornaments, and nurtured dollar-earning

exports.1 It had husbanded its reserve for future purchases of resources for

its war economy, inflicting "the curse of gold" on its people by a

"wholesale attack on the standard of living." At the end of the war,

although the economy was in a shambles, the government of Japan was awash in

gold amounting to twice its hoard in 1941. After the surrender the gold and

silver in the Bank of Japan and other government vaults was sequestered by

MacArthur's occupation forces. As to Japan's frozen dollars, they were never returned.2

A contemporary

journalist summed it up. He could not have known that for four years, U.S.

Treasury and Federal Reserve analysts had predicted Japan would soon exhaust

its assets and necessarily abandon its aggressive policies. However, he wrote,

"Japanese leaders exerted every possible effort to avoid this outcome.

They succeeded .... Gold production was stimulated A vast foreign exchange

reserve was maintained." Although U.S. forecasts of empty vaults proved

false, Japan was plunged into the international bankruptcy they predicted

because of a stroke of a pen in Washington.3 Two views, one American and one

Japanese, illustrate the attitudes about Japan's bankruptcy on the eve of war.

When Dean Acheson

arrived at the State Department in January 1941 he rediscovered the prodigious

powers of Section 5(b) of the 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act. He and

colleagues of like mind promoted its deployment against Japan, then twisted a

cautious squeeze designed "to bring Japan to its senses, not its

knees" into strangulation. Acheson, an officer of the department charged

with peaceful solutions through diplomacy, boasted to Cordell Hull on 22

November 1941 that financial crippling had proven far more devastating to Japan

than embargoes. The freeze administrators thwarted Japan from removing its

dollars from U.S. control as it had been doing for a year. Their actions

slashed U.S. exports to zero despite Japan's valid export licenses for oil, and

other licenses it would have been entitled to for cotton, lumber, and

foodstuffs. Nor could Japan pay the mineral-rich nations of North and South

America or the Dutch Indies, which demanded dollars, while the sterling bloc

joined in the freeze. U.S. markets abruptly closed to Japan. Washington refused

to allow Japanese trading companies to receive dollars, even if paid into their

blocked accounts, hastening the ascendancy of nylon, which devastated silk

farmers and demolished Japan's largest renewable flow of dollars.4

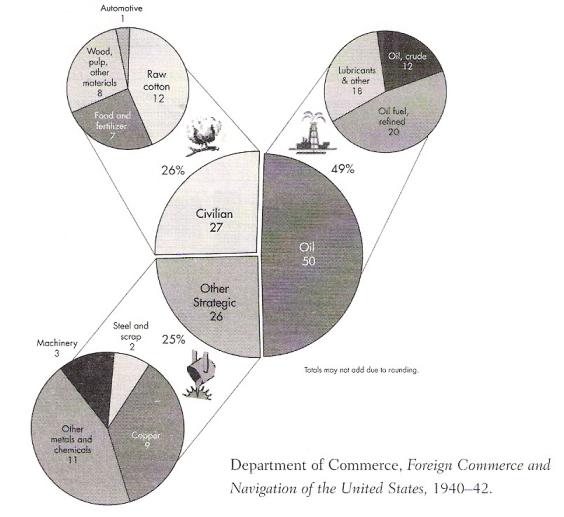

U.S.Forecasts of Japan’s International “Bankrupty,”

1937-1941

In Japanese eyes the bankruptcy

was a lethal threat, an assault on the nation’s very existence. After the war,

Koichi Kido, lord keeper of the privy seal and adviser to Emperor Hirohito,

delivered an eloquent statement through his American defense counsel, William

Logan Jr., before the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. (Kido

was found guilty of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment but was

released in 1955.) Kido styled his defense “Japan Was Provoked into a War of

Self-Defense.” Allied charges of war crimes defined aggression as “a first or

unprovoked attack or act of hostility.” Kido argued that strangling an island

nation dependent on foreign resources was a method of warfare more drastic than

physical force because it aimed at undermining national morale and the

well-being of the entire population through starvation. A nation, he concluded,

had the right to decide when economic and financial blockade was an act of war

that placed its survival in jeopardy. Kido thereby harked back to the dawn of

international law three centuries earlier when jurists held that refusal to

sell to another nation might well be a valid casus belli under extraordinary

circumstances such as starvation.The defense added,

“We know of no parallel case in history where an eco

nomic blockade … was enforced on such a vast scale with such deliberate,

premeditated, and coordinated precision …. Responsible leaders at that time

sincerely and honestly believe[d] that Japan’s national existence was at

stake.” Because sanctions “threatened Japan’s very existence and if continued

would have destroyed her,” the “first blow was not struck at Pearl Harbor.”

Indeed, Lojan continued, the “Pacific War was not a war of aggression by Japan.

It was a war of self defense and self

preservation.”5

The OSS Document

Unfortunately for

Japan, its leaders chose a war that brought upon it far more economic

devastation than any sanctions, along with great loss of life and untold

misery. Although struggling along under bankruptcy without going to war was a

dreary prospect, a third course was open to Japan: renouncing imperial

aggression in return for thawing of the freeze. One may wonder, what if Japan

had endured the freeze long enough to ascertain that Germany could not win and

had then abandoned the Axis, perhaps even joined the Allied side as it had in

1914? It would have prospered mightily by selling ships, machinery, and other

goods to the Allies. It would have emerged after the war as the strongest

regional power, with a world-class navy, an overflowing treasury, and a zeal

for industrial modernization, just as colonial empires in Asia were crumbling.

It might have shored up China against communism. A cooperative Japanese

commercial "empire" in East Asia, economically buoyant and trading

internationally on a grand scale a generation sooner, could have changed the

course of history in the twentieth century and beyond.

Arthur B. Hersey titled his study for the Office of

Strategic Services and the Department of State "The Place of Foreign Trade

in the Japanese Economy; an analysis of the external trade of Japan proper

between 1930 and 1943 focusing on possible or probable postwar development."

He comprehensively analyzed Japan's external trade with both the yen bloc and

the rest of the world in three representative prewar years: 1930, 1936, and, to

a lesser extent, 1938.6 His goal was to outline a possible range of conditions

of Japan's economy about five years after the end of World War II to assist

U.S. planners contemplating post-surrender and occupation policies. The

methodology was complex. To link actual past to hypothetical future years

Hersey converted physical units (pounds, bales, square yards, calories, etc.)

to a common denominator of "constant yen," a proxy for physical units

that also allowed him to adjust erratic prices of internationally traded goods

into more comparable units.7

During the war many

economists expected a return of the global Depression after a brief postwar

boom. Hersey believed Japan's future in international trade to be especially

bleak. Its appetite for imports of minerals, industrial crops, machinery, and

even foodstuffs was almost unbounded. But its capacity to import would be

limited to the hard currency it could earn from exporting goods and services

and from gold mining. (He considered foreign loans unlikely.) In the 1930s

Japanese exports had expanded rapidly, but the benefits to the people had been

circumscribed for several reasons. A rising share of exports went to the yen

bloc, which could neither pay in hard currency nor deliver the most needed

commodities. While foreign countries erected barriers against Japanese goods,

the terms of trade (relative world prices) worsened after 1930. No foreign

loans were available due to disorganized financial markets in America and

Europe and active discouragement of lenders by those governments because of

Japan's aggressions.

"The core of the

analysis," Hersey wrote, was a classification of Japan's imports

(typically 90 percent raw and semiprocessed materials

and foods and 10 percent manufactures) into two categories: commodities

required by factories that manufactured products for export and commodities for

final consumption within Japan. The latter, labeled "retained

imports," comprising 59 to 68 percent of all imports in the 1930s,

contributed directly to the standard of living. Another 25 percent of imports

were materials for processing and resale abroad, primarily raw cotton for

textiles, wood pulp and salt for rayon, and metals, chemicals, and fuels for

other manufactures. A final 8 percent of imports were offsets to exports of a

similar nature, swapped, in effect, because Japan both bought and sold in

various grades and processed forms, wheat, sugar, fish, coal, and fertilizer.8

Japan's greatest dilemma in the 1930s, Hersey believed, had been deterioration

of the "barter terms of trade," that is, weak export prices and high

import prices. Japan had to run harder to stay in the same place

internationally. For consistency he recast the data into indexes of

"constant yen" at 1930 terms of trade. (He also calculated 1936 and

1938 terms of trade although they were of less relevance to his conclusions.)

Hersey selected 1930 as a "best case" year, similar to the relatively

prosperous 1920s, and the last equilibrium year of Japan's international trade

before the turmoil of world depression, yen devaluation, the Manchurian

adventure, and foreign trade discrimination. In 1930 Japan's upscale products

enjoyed high prices abroad, notably raw silk and silk fabrics, premium

seafoods, fine pottery, and other consumer luxuries, while prices of raw cotton

and most other imported agricultural and forestry products were low. (Japan did

not yet import oil, metals, or minerals on a large scale in 1930, and not much

machinery).9

A terms-of-trade

index is not the same as the familiar domestic price index. It is a ratio of

relative prices, that is, an export price index divided by an import price

index. Hersey calculated data for twenty internationally traded product classes

that he aggregated into eight groups: food; fertilizer and fodder; coal and

petroleum; metals and minerals; cotton, wool, and pulp for rayon; lumber and

paper pulp; and manufactured goods. He assigned to the terms of trade in 1930

an arbitrary index number of 100. The index for any other year, actual or

predicted, was that year's export price index divided by its import price

index. A resulting index above 100 meant a favorable trend for Japan, and vice

versa for numbers below 100. Although any prediction was "pure

guesswork," Hersey admitted, a postwar Japan enjoying 1930 terms of trade

could fare adequately in the world, though not richly. "It is

doubtful," he opined, "whether Japan's terms of trade will under any

circumstances be more favorable than they were in the 1920s and 1930."

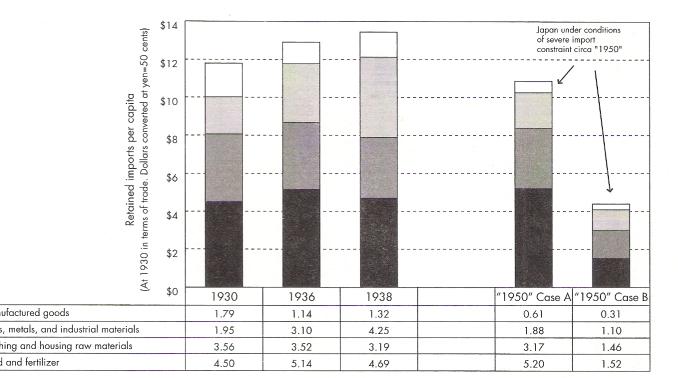

Hersey examined the

improvements of the Japanese standard of living before the war. Economists had

been awed by a surge of retained imports-79 percent higher in 1936 and 86

percent higher in 1938 compared with 1930but the benefit to ordinary Japanese

families was somewhat illusory. Yen devaluation, worsening terms of trade, and

a massive switch to importing and stockpiling of industrial and strategic goods

left the rise of retained imports for the benefit of the public at only 14

percent, barely more than population growth of 9 and 12 percent respectively

since 1930. Yet the Japanese standard of living had undeniably improved, by

about 10 percent per capita. Food consumption per capita was thought to be

unchanged; the rising population was fed from rising domestic farm output

through intensive fertilization. Gains in nonfood goods and services ranged

from 20 percent to more than 30 percent per capita. As with food, the gains

were mostly achieved by surges in production from domestic resources, notably

chemicals, electrical energy, and paper, and by the effect of rayon pulp (10

percent of textiles cost) substituting for raw cotton (50 percent of textile

cost). The experience implied that if postwar Japan could import consumer needs

for its populace at the 1930 rate in real terms per capita, reduction of the

standard of living would be tolerable, although disappointing for a population

used to improving conditions.10

For his "highly

tentative" postwar models of trade and living standards Hersey adopted the

hypothetical year" 1950" to represent a date a few years after the

war when physical reconstruction would be largely completed, production of most

domestic-sourced goods recovered, and crop yields normal. Population growth was

a crucial assumption. Japan's population had risen steadily at about 1 million

per year, from 64.4 million in 1930 to 72 million in 1938. Expecting

continuation of that rate, Hersey expected a population increase to 81 or 82

million in "1950," after adjusting for war casualties and

repatriation of Japanese émigrés from Asia.11 For a country that historically

found difficulty in feeding itself, millions of extra mouths would intensify the

dilemma of maintaining living standards in the face of weakened exports. Three

adjustments have been made here to adapt Hersey's data from "1950" to

represent Japan in, say, 1942, under a freeze but not at war with the Allies.

First, the population differences between the periods of seven to eight million

people are neutralized by converting trade to per capita values. Second, yen

are converted to dollars at appropriate exchange rates. Third, his eight

commodity groups are simplified into two: consumer commodities and other.

Japan's postwar

future was clouded by an anticipated vicious cycle of trade: uncertain markets,

adverse prices, and technological changes (notably the substitution of nylon,

reducing raw silk exports by an assumed 50 percent)12 resulting in a shortage

of hard currency to buy raw materials for factories that produced for export.

The uncertainties were profound. Rather than guess at world appetite for

Japan's specialized goods, Hersey found it easier and surer to calculate

imports essential for survival of an impoverished populace. He therefore set

imports as the independent variable and assumed two levels of

"retained" and other imports. He then "reverse engineered"

his models to determine the exports necessary to fund the purchasing abroad.

Japan's exporting capability became the dependent variable. Hersey developed

two scenarios of the Japanese standard of living in "1950" by

arbitrarily assuming two levels of nutrition, expressed as daily calories per

person, which set an upper limit on non-food imports. Case A assumed the 2,250

calories prevailing in 1930, which had not increased much if any in the

following ten years. Assuming, however, that Japan's capacity to harvest crops

and fish had topped out by 1941, a larger share of its limited postwar earnings

would necessarily have to pay for imported food, fertilizer, and fishing boat

fuel. Imports of materials for clothing, shelter, and infrastructure would have

to be severely constrained by government priority rules, leaving little or

nothing for other consumer goods such as foodstuff varieties. The procedure

resulted in reduced postwar living standards of 25 to 33 percent depending on

the details assumed.13

Case B envisioned a

horrendous outcome for the Japanese people because of an exporting capacity so

enfeebled that not even basic nourishment and health could be maintained.

Hersey arbitrarily assumed a 20 percent reduction in nutrition below Case A, to

1,800 calories per person per day. Food and fertilizer needs would overwhelm

other import priorities. Only minor imports could be financed for other

consumer needs and urgent infrastructure. Retained imports per capita would

slump 67 percent below 1930.14 Hersey also calculated terms of trade for 1936,

the last peacetime year and a "worst case" year for Japan. Raw silk

prices had fallen disastrously. Textiles and other wares were restricted by

U.S. tariffs and quotas and by British imperial preference. Although exports of

chemicals and mechanical products-bicycles, sewing machines, industrial

machinery-held up better, Japan mostly sold them to the empire for yen.

Meanwhile, prices of

imported commodities were propped up by dominant suppliers such as U.S.

government supports of cotton. (Strategic metals and fuels remained relatively

cheap but were minor items of import before the war in China.) Relative to a

1930 index of 100, export prices in 1936 dropped to 95 whereas import prices

soared to 129. Japan then had to sell 33 percent more goods to buy the same

basket of imports. Because Hersey assumed the value of other imports as equal

to Japan's residual buying power after meeting food and fertilizer needs, the

large difference between 1930 and 1936 terms of trade dictated a necessity of

much larger exports, but did not alter his Case A and B models of

"1950." For example, Case A, calibrated to the 1936 terms of trade,

required 55 percent more exports versus the 1930 terms of trade model, $1.62

billion versus $1.05 billion, to achieve the same standard of living

established by Hersey's assumptions. (Hersey did not itemize exports in detail

as he did for imports because of extreme uncertainty over the products Japan

could sell, and to which countries, after the war.) Despite Japanese censorship

of data from 1936 onward, Hersey calculated a somewhat improved 1938 terms of

trade index but did not rely on it because distortions caused by the war in

China, commodity stockpiling, and a renewed U.S. depression that lowered the

cost of Japanese imports rendered it irrelevant to his vision of

"1950."15

As indicated above,

Japan's de facto bankruptcy proved a crucial factor in the failure of

negotiations for a peaceful settlement with the United States. The diplomatic

maneuverings of 1940-41 have been exhaustively described in documents, memoirs,

diaries, interviews, postwar investigations, and war crimes trials.16 Thus we

briefly summarize the events, focusing on the significance of the dollar

freeze. U.S. resentment against Japanese aggressions began with the seizure of

Manchuria in 1931 and accelerated when Japan assaulted China in 1937. The'

country initially reacted with diplomatic scolding’s, aid to China, and

embargoing exports of a few arms-related products. In 1940 tensions grew acute

when Japan signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy whereby the three

powers pledged to assist each other in wars, under certain circumstances. The

United States, inching toward war in the Atlantic through pro-British policies,

grew concerned that it might have to fight Japan as well. Negotiations for a settlement

of tensions began in earnest in April 1941. All discussions were conducted in

Washington between Ambassador Kichisaburo Nomura

(assisted after 15 November by special envoy Saburo Kurusu) and Secretary of

State Cordell Hull. The Japanese diplomats also met directly with President

Roosevelt, and occasionally with civilian and naval officials Nomura new

personally.

Other U.S. officials

played relatively minor roles.17 Hull advanced four "principles" for

Asia: respect for the territory and sovereignty of all nations, noninterference

in their internal affairs, equal commercial opportunity, and maintenance of the

status quo in the Pacific-the principles established by the Nine Power Treaty

of 1922. For Japan the main stumbling block was surrendering its decade of

conquests by withdrawing from Indochina and China, perhaps even from Manchuria.

In Japanese eyes a retreat would mean giving up any possibility of gain from a

war that had cost two hundred thousand dead soldiers, required huge outlays of

national treasure, and caused economic hardships for its people. The United

States further demanded assurances that Japan would renounce the Tripartite

Pact, or at least refrain from fighting it as an ally of Hitler. To prod Japan,

Washington embarked on three programs: arms and financial aid to China, a

buildup of forces at Pearl Harbor and in the Philippines, and barring exports

of commodities needed for its own defense.

The Japanese position

was, simply, resistance to Hull's proposals: no U.S. interference in

China-Japan affairs, no military withdrawals from occupied territories,

maintaining ties with Germany, and continuing trade with the United States. In

1941 events in Europe emboldened Japanese leaders. Hitler's attack on Russia on

22 June quelled the army's fears of a Soviet attack on the empire, and it

joined the navy in favoring a war to seize the resources of western colonies in

Asia. On 24 July, Japan, having coerced Vichy France, occupied southern

Indochina, triggering the U.S. freezing orders two days later and those of the

Allies soon after. After 26 July 1941 Japan's priority shifted to demanding an

end of the dollar freeze, or at least an easing so that deliveries of oil and

perhaps other strategic commodities might resume. At first Tokyo phrased the

aim in generalities while its representatives in the United States searched for

loopholes. In August banking and consular officials petitioned for financial licenses

to pay for two shiploads of oil and probed the possibilities of paying with

dollars or gold held outside the frozen accounts. They were rebuffed at every

turn by the Foreign Funds Control Committee dominated by Dean Acheson.

Early in August Prime

Minister Prince Fumimaro Konoe launched an initiative

to meet with President Roosevelt personally, perhaps in Hawaii or Alaska, in

what later generations would call a summit meeting. To placate the generals and

admirals, Foreign Minister Teijiro Toyoda drafted

demands that the United States halt reinforcement of the Southwest Pacific,

mediate a peace settlement in China (a euphemism for abandoning aid to Chiang Kai-Shek), and restore normal commercial

relations (a euphemism for ending the freeze). In return Japan offered not to

advance beyond Indochina and to withdraw troops from China when the war ended

at some vague future date. FDR was intrigued but the State Department deemed

the tradeoffs unacceptable, especially because Japan refused to start

evacuating promptly. The United States declined the summit offer.

Japanese military and

naval leaders moved forward with plans to launch a war before the year was out.

On 6 September 1941 an imperial conference agreed to make a decision during the

first ten days of October about war against the United States, Britain, and the

Dutch Indies (a deadline gradually moved back to 29 November) unless Japan's

demands were met.3 On 18 September Acheson disclosed that the United States had

rejected Japan's last ditch barter scheme of oil for silk. Mobilizing for an

attack began in earnest in Tokyo in the second half of the month. Nevertheless,

Toyoda wished to test other avenues of negotiation. The deadlock between the

war hawks on one hand and Konoe and Toyoda, who favored some troop withdrawals,

on the other hand, led to the fall of Konoe and his replacement as prime

minister by General Tōjō Hideki on 17 October. Last-chance diplomacy

passed to a new foreign minister, Shigenori Togo.

Japanese agents had

continued to poke about desultorily for token financial licenses for oil or

minor freeze-evading transactions, without success. On 24 October, however,

Acheson told Counselor Tsutomo Nishiyama that the

looming insolvency of the Yokohama Specie Bank in New York, where Japan had

mobilized its dollars-a bank failure engineered by the U.S. government's

barring the bank from collecting money for silk delivered to the United States

before the freeze-would permanently lock up Japan's main holding of blocked

dollars. It was clear that oil cargoes would never sail. This casting away of

hope immediately preceded Tokyo's decision to demand financial relief, explicit

in time and very substantial in amount, countered by American musings of barter

concessions much below Japanese needs.

As resource

stockpiles dwindled, and with the military's reluctant consent, Shigenori Togo

proposed "Plan A," an offer reciting kinder words about free trade in

China but standing firm on the Axis pact and rejecting troop withdrawals for

twenty-five years. As expected, Hull rebuffed it. Togo followed with "Plan

an interim truce. Japan would evacuate Indochina if the United States kept its

nose out of China, resumed trade promptly at pre-freeze levels, supplied oil in

abundance, and prodded the Dutch to supply more.19 The army insisted on

amending Plan B so that "the United States will promise to supply Japan

with the petroleum it needs." On 14 November the generals defined their

terms:

The United States

must sell a tonnage of oil equivalent to 42 million barrels per year (converted

here at 7 barrels per metric ton), including 10.5 million barrels of avgas, and

ensure another 14 million barrels from the East Indies. If the Dutch did not

agree, Japan would occupy the Indies. If the United States did not comply one

week after signing an agreement, war would begin. Shigenori Togo and

General Tōjō Hideki scaled down the extravagant demands to 28 million

barrels of U.S. oil, still a wildly improbable figure 34 percent greater than

the annual rate of U.S. sales in January-July 1941. The amount was 259 percent

greater than the 7.8 million barrel annual quota based on 1935-36 that

Washington had contemplated in August for possible trade resumption. Avgas had

been effectively embargoed since December 1939. Nomura did not present the

exorbitant demand because Hull's response to Togo's first plan intervened.20

In November special

ambassador Saburo Kurusu arrived to assist Nomura, whose English was not the

best. As presented to Hull on 20 November, Plan B proposed evacuation of

Indochina, American noninterference in China matters, restoring pre-freeze

trade, including an undefined volume of oil, and helping obtain Indies

resources. Considering the plan "preposterous," Hull pondered a

response, urged by the military services to buy time for defense preparations

and by China and England not to go soft.6 On 18 October Hull had mused to Lord

Halifax, the British ambassador, about a minor swap of silk for cotton-not

oil-in exchange for a promise of a status quo in the Pacific. Anxious to avoid

a rupture, the Japanese envoys suggested another humble accommodation: small

quantities of U.S. rice and oil for Japan, far less than its full requirements,

with guarantees that none would go to its armed forces. Hull was willing to

think about it. Roosevelt informed Winston Churchill that the United States

might thaw the freeze slightly on quasi-barter terms, strictly for civilian

goods, for a three-month trial. The United States would license exports of food

products, ships' bunker fuel, pharmaceuticals, raw cotton worth up to six

hundred thousand dollars per month, and some petroleum for civilian needs while

encouraging the Dutch to supply more. Yet the United States would not unfreeze

Japan's dollars. Instead, it would buy Japanese products, two-thirds of which

was to be raw silk-about 5 percent of the pre-freeze rate of silk purchases-just

sufficient to finance the U.S. exports and to service Japanese bonds owned by

Americans.7 But the gesture, overtaken by the onrushing crisis, was never

offered to Japan. For six crucial days in November Hull played with notions of

a modus vivendi ("manner of living"), a standstill of three months

during which Japan would abandon southern Indochina, limit forces in the north,

and commence peace discussions with China. In return the United States would

unfreeze some Japanese dollars and resume some exports, although export

controls in effect "for reasons of national defense" would remain. It

would encourage the British and Dutch to act similarly. Between 20 and 26

November, Hull reviewed a slew of proposals and modifications from administration

officials that watered down his proposal. Acheson's boastful report of the

excellent results of the financial freeze arrived on his desk. By 24 November

Hull's draft conceded a barter-type exchange of raw silk for oil and other

goods, amounts not specified, but no release of blocked dollars.

The eviscerated modus

vivendi was never offered to the Japanese. Allied scouting planes spotted a

troop convoy heading for Thailand and Malaya. Landings there were sure to

provoke war. On 26 November Hull's definitive response, approved by FDR,

retreated all the way back to stiff-necked demands for the four principles and

unlinking from Germany. General Tōjō Hideki deemed deemed it an ultimatum.23 When six Japanese aircraft

carriers sorties from the Kurile Islands, Washington sent a war warning to

Pearl Harbor and other bases. An imperial conference of 1 December gave up on

negotiations and decided irretrievably that the empire would attack. On 4

December the southern invasion force sailed for Malaya from Hainan Island. On

the sixth Roosevelt made a futile personal appeal for peace to Emperor

Hirohito. On 7 December Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. The two nations were at

war.

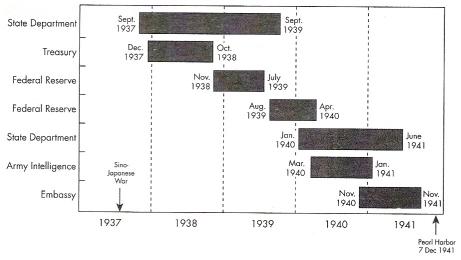

Japan Sources of Dollars, Actual, 1939-1940, and

Projected, 1941-1943

Japan: Retained Imports per Capita, 1930s and “1950”

Projections

Sources Including For Further Research

The focus of this

case study is the United States' financial and economic sanctions against Japan

before Pearl Harbor, reconstructed primarily from official U.S. sources. Many

histories have been written about the run-up to the Pacific war, largely by

diplomatic historians, understandably in view of the centrality of the

Department of State in U.S.-Japanese negotiations and that department's

voluminous, well-organized files, which were declassified long ago, some as

early as 1943, supplemented by forty volumes of congressional hearings of 1946

about Pearl Harbor and precursor events.35

Not until 1996 did

the National Archives, at the prompting of a U.S. interagency group on Nazi

assets, declassify and make more readily available the worldwide papers of the

Treasury Department's Office of the Assistant Secretary of International

Affairs, established on 25 March 1938 and directed by Harry Dexter White.36

These records contain a trove of U.S. assessments of Japan's financial

problems, and U.S. proposals to exploit them, that have not appeared in other

histories. A similar wealth of information is in the records, first opened to

the public in 1996-97, of the Division of International Finance of the Board of

Governors of the Federal Reserve system, primarily from 1935 to 1955. The

Federal Reserve Bank of New York voluntarily sent to the National Archives

those of its records "that relate to the activity in accounts for foreign

governments" in the same era.37 The files of the U.S. Alien Property

Custodian, which include the 1880-1942 records of Japanese bank branches in the

United States seized in 1941, were closed until fifty years after seizure to

researchers lacking special permission and were inconveniently located until

transferred to the National Archives II in 1995-96 and "bulk

declassified." The records of the Tariff Commission (now the U.S.

International Trade Commission), with a wealth of studies on specific Japanese

products, were open but not properly described and arranged until 1992.4 The

planning records of the Administrator of Export Control, the office that led

the drive for sanctions against Japan during the crucial months of September

1940 to May 1941, were difficult for researchers to use until recently, when

they were rearranged and a finding aid was prepared at the National Archives.

That office was subsumed in September 1941 into the vast wartime bureaucracy of

the Foreign Economic Administration, which in turn was reorganized three or

four times during the war. Its boxed records extend 3,817 cubic feet and weigh

seventy-five tons. A comprehensive catalogue of all international records of

the era, which are mostly located at National Archives II in College Park,

Maryland, was completed in 1999 under the direction of Greg Bradsher and is

available online at http://www.archives.gov/research/ holocaust/finding-aid.

The main Japanese

sources are the excellent historical data published in bilingual tables by the

Japan Statistical Association, and Japanese commercial and diplomatic studies

published in English. Most of Japan's official records of 1931 to 1945 were burned

in the two-week interval between the surrender and the occupation in 1945 in

anticipation of war crimes trials. However, economic information for the last

prewar decade was reconstructed in detail and published by the U.S. Strategic

Bombing Survey and by investigators of the Supreme Commander of the Allied

Powers during the postwar occupation. Japanese financial and trade statistics

are usually presented for fiscal years beginning I April, so that, for example,

"1940" means the twelve months beginning 1 April 1940 and ending 31

March 1941. U.S. statistics are usually given for calendar years, making some

comparisons awkward. Physical trade units are stated here in U.S. measures such

as ounces, tons, or yards, or occasionally in metric measures. Some Japanese

figures have been converted from metric units or the ancient weights and

measures then used in trade.

Money figures are

stated in U.S. dollars, the dominant world currency then and now. The 1935-41

dollar was worth about $10 in 2007 dollars if measured by an average of U.S.

prices of goods, or about $25 if measured by average U.S. wages. In exchange

markets the yen was worth 49 to 50 cents from 1899 until devalued on 14

December 1931. It dipped as low as 20 cents in 1932-33, then stabilized at 28.3

cents until 24 October 1939, when it was devalued to 23.4 cents. There was no

organized exchange market after 25 July 1941; fragmentary trading in China

suggests that in late 1941 the yen's gray market value was much lower, perhaps

II or 12 cents.5 After a devastating wartime and postwar inflation, the yen was

stabilized at 0.28 cents (360 per dollar). It subsequently has risen to almost

I cent (l00 per dollar). The U.S. economy is roughly 150 times larger than in

1935-40 in unadjusted dollars and about 10 times larger adjusted for price

inflation. The Japanese economy is about 500 times larger in unadjusted U.S. dollars

and about 50 times larger adjusted for U.S. inflation. The prewar Japanese

economy was about 8 percent the size of the American. In 2006 it was about 40

percent as large. Japanese foreign trade is now about seven hundred times

greater in nominal value, $1.1 trillion versus $1.5 billion before the war, of

which half was within the "yen bloc." (Both figures are unadjusted

for inflation.) To grasp the relative significance in twenty-first century

terms of $100 million in 1941, a very large fraction of Japan's international

liquidity at the time, the reader may wish to multiply by a factor of one

thousand.

As seen above, the

United States forced Japan into international bankruptcy to deter its

aggression after Washington experts confidently predicted that the war in China

would bankrupt Japan. However, the United States did not know the Japanese

government had a huge cache of dollars fraudulently hidden in New York. Once

discovered, Japan scrambled to extract the money. But, in July 1941 President

Roosevelt invoked a long-forgotten clause of the Trading with the Enemy Act of

1917 to freeze Japan s dollars and forbade it to sell its hoard of gold to the

U.S. Treasury, the only open gold market after 1939. Roosevelt s temporary

gambit to bring Japan to its senses, not its knees, was thwarted, however, by

opportunistic bureaucrats. Dean Acheson, his handpicked administrator, slyly

maneuvered to deny Japan the dollars needed to buy oil and other resources for

war and for economic survival. So it is to the oil issue we now turn, continue...

1 Herbert Feis,

Economic Adviser, "Japan's Ultimate Foreign Exchange Resources," 20

September 1937, Box 21, File Japan Foreign Exchange Position, OASIA.

For updates

click homepage here