A Dark Age guerrilla leader, a cavalry

commander repelling the Saxon hordes - this is the modern version of Arthur,

presented in recent books and films. This first incarnation of Arthur, however,

is only recorded well over three hundred years after these events. He first

appears in the History of the Britons, written in 830, as a heroic British

general and a Christian warrior. Attributed to a writer called Nennius, the

History of the Britons was a riposte to the patronizing English attitude

towards Welsh history. But these stories are obviously mythic in character, the

Dark Age Che Guevara verging towards the later medieval Superman.

Our one contemporary source from the

sixth century, Gildas, does not mention him and tells us that the British

leader in these battles was called Ambrosius. The case for a fifth- or

sixth-century Arthur fighting Anglo-Saxons in southern Britain looks decidedly

flimsy. He is simply not there. So who was Arthur? And where was Arthur?

The legend of Arthur as a heroic

Christian warrior starts in the ninth century in Nennius's pseudo-history.

Partly perhaps a product of Nennius's own imagination, Arthur begins as a

Celtic folk hero: a response to the growing power of the English - and to the

growing realization by the Celts that the invaders were here to stay. Whether

Arthur was a historical character in fact was of no concern to earlier writers.

The growth of his legend was in response

to the cultural and political needs of the time, just as the Arthurs of

Geoffrey of Monmouth, Malory, Spenser and Tennyson would be. But the story

was also part of a bigger theme: the Matter of Britain.

By Nennius's time - the Viking Age - the

subjugation of lowland Britain had been achieved by the Anglo-Saxons, and a

number of small kingdoms had been established. These kingdoms had adopted

Christianity and had developed a sense of identity as an English nation. Taking

a leaf out of Gildas's book, their historian Bede had portrayed the English as

a chosen people destined to rule the island of Britain, which the Celts had

lost because of God's judgement on their failings. The Matter of Britain now

had a rival: the Matter of England.

And just how these political and

cultural struggles were reflected in the literature of the day is neatly

revealed by two tenth-century poems from either side of the racial divide.

Still fondly hoping for the overthrow of the English, a Welsh cleric in South

Wales wrote the Great Prophecy of Britain - the greatest of all Welsh prophetic

poems, which would serve as a literary model for Merlin's prophecy of Arthur in

Geoffrey of Monmouth's work. In it Myrddin, the prototype of Merlin, foretells

that the Welsh will rise up, and with the help of the Irish, Scots, Bretons and

Cornish - the old Celtic world united once more - will drive the English `pale

faces' out `at Aber Sandwich' (where they had first landed). `We will pay them

back for the 404 years,' he wrote, `and the Britons will rise again.' When

these hopes were crushed at the battle of Brunanburh,

an Old English poet gloated in his turn: `Never was there such a victory since

the Angles and Saxons first sailed over the broad waves, sought out Britain,

overcame the Welsh, and seized the land.' So both poets harked back to the

Coming of the English. However, the Welshman had called not on Arthur but on

the heroes Cynan and Cadwalladr as the chieftains who would drive the English

out. In the tenth century, then, Arthur was the focus of many local legends but

not yet a pan-British hero. But his time was about to come. Soon enough the

prophesies would become attached to an Arthur in the making.

In 1066 England fell to the Normans, who

soon invaded the Celtic kingdoms too, and in the later 1100s began the attack

on Ireland, initiating a chain of bloody events whose aftermath only began to

be untangled in the twentieth century. It was in the first generations after

the Norman Conquest that the Matter of Britain began to be articulated in myth

and literature as a central theme in the mainstream culture; we are now

entering the great phase of Arthurian myth-making.

Myths and legends are often crystallized

in interesting times, times of crisis or opportunity. And the early twelfth

century was certainly that. Without doubt 1066 had been a disaster for everyone

in the British Isles, but for all the cruelty and devastation the arrival of

the Normans unleashed tremendous cultural energies, initiating exchanges and

contacts, especially with the French-speaking world, that would transform the

Arthurian tales.

The 1130s were a time of anarchy,

violence and war in England and the Celtic lands. The Norman subjugation of

Wales had gone on apace, despite Welsh protests that they were `trying to wipe

out the British so well that even the name be forgotten'.

The military war was also accompanied by

a cultural war on the Celts, who were pictured as barbarians in need of

civilizing. As a French writer put it, `the Welsh are savage by nature, wilder

than the beasts in the field.' These political and cultural struggles came to a

head in the great Welsh revolt of the 1130s, when the rebels hoped `to restore

the British kingdom'. There were dramatic reverses for the Anglo-Norman

occupiers: their leaders were killed, their armies defeated, castles taken and

large tracts of Wales reclaimed. The mood of the time in Wales is crystallized

in a poetic text of the 1130s: `The Welsh openly go around saying that in the

end they will have it all ... through Arthur they will get it back ... They

will call it Britain again.

These were grassroots ideas whose

origins lay far back in time. Arthur had in fact already been claimed in the

previous century by Welsh nationalists, who also believed that he would one day

return. `Marvellous stories of King Arthur have of

Britain' - he never once mentions `England' - he set out to provide the British

with a new national mythology masquerading as history. But where English

historians such as Bede and William of Malmesbury had attempted to do the same

thing within the confines of historical data - albeit directed and given

meaning by Christian ideology and God's miraculous interventions in human

affairs - Geoffrey cut loose from mere historical fact. He claimed to have

discovered a lost history of the Celts which he alone had read and translated,

and which was the authority behind his saga of two thousand years and

ninety-nine kings. Starting in 1115 BC (note the confident precision!), this

was Celtic history as people dreamed it might have been - and as it still

perhaps could be.

On the way Geoffrey gives us a gallery

of characters, many of whom became stars in their own right in the literature

of the Middle Ages and Renaissance: Cymbeline, Bladud, Leir and Merlin among

them. Right at the centre was the figure of Arthur,

now king. In Geoffrey's pages Arthur is a hero who bestrides Europe like a

colossus: a Napoleon of the Roman twilight. For the first time his whole life

is told: his birth at Tintagel, the son of Uther Pendragon; his battles, and

his campaigns in Europe; his eventual betrayal. There's Guinevere and Merlin,

and the treacherous Mordred; there's Caliburn, the

future Excalibur; and even the king's final resting place at Avalon.

To add verisimilitude and local colour, Geoffrey also cleverly used local legends and folk

tales about sites with Arthurian associations. For example, travelling in the

southwest he seems to have heard a story about Tintagel as the birthplace of

Arthur, and his tale of Arthur's conception by Uther Pendragon is enriched with

circumstantial local detail: he mentions, for example, the fortified camp at Dimilioc, 8 kilometres from

Tintagel, today's Castle Dameliock. The Cornish

tourist industry, for one thing, would never look back.

Even in his own day Geoffrey was

attacked by English historians as a `spinner of tall stories which should be

rubbished by everyone'. As for the lost manuscript, which he claimed as the

basis for his book - the secret history of the kings of the Britons which he

alone had been able to examine - this surely is as tongue-in-cheek as the

manuscript in Moorish script that supposedly gave Cervantes his tale of Don

Quixote. Lost manuscripts have an honourable

tradition in fictional literature, right down to Borges and Umberto Eco; and as

a device to torpedo the smug Anglo-centricity of the likes of William of

Malmesbury, Geoffrey's worked a treat. The Celts might have lost the political

war in the Middle Ages, but they would win the literary battle hands down.

So, fantasy it may be, but Geoffrey of

Monmouth's book is the real creator of Arthur as we know him. Moreover, one of

Geoffrey's themes, which recycled the political rhetoric of his own day, would

be crucial for the future. At the centre of his tale

is an extended sequence of Merlin's prophecies culminating in the omen of `a

star appearing in the sky, its head like a dragon from whose mouth two beams

came at an angle, one across Gaul, one towards Ireland: and the beam of light

was Arthur himself and the kingship of Britain'. After the fateful last battle,

and the wounded Arthur's journey to Avalon, in a literary master-stroke

Geoffrey leaves us in suspense: perhaps Arthur is not dead. An angelic voice

assures the Celts that `the British people would reoccupy the island in the

future, once the appointed moment would come'.

And did he really believe that? Reality,

unfortunately always intrudes. After all, Geoffrey was a modern man in Oxford

in the mid-1130s; the facts of contemporary history spoke for themselves. So,

after all the literary fireworks Geoffrey ends on a curious note of

disappointment and defeat for the Britons (coloured

perhaps by the crushing of the Welsh revolt in 1138 as he wrote?). The Saxons

had won and now were `opposed only by those pitiful remnants of Britons who

dwelt in the forests of Wales ... Britons who now called themselves not Britons

but Welsh'. He ends with a reflection worthy of Gildas: `And the Welsh, once

they had degenerated from the noble state enjoyed by the Britons, never

afterwards recovered the overlordship of the island.'

Geoffrey plainly could not escape the

curve of history as seen in the late 1130s. These days his brilliant fantasia

on early British history is often seen as an academic leg-pull, a playful jeu

d'esprit. But Geoffrey launched Arthur and the Matter of Britain into a

stratosphere of myth which it has occupied ever since.

So Arthur of Britain was born. In its

own day Geoffrey's book had a tremendous influence: over two hundred

manuscripts survive today - more than there are of Bede's work - and it had as

big an impact in Europe as in Britain. Geoffrey seized the imagination of

Europe, inspiring medieval romancers and chroniclers from Chrétien de Troyes

and the courtly love poets to the German Wolfram von Eschenbach, and on down to

Malory, Spenser, Shakespeare, Dryden, Tennyson, William Morris and the

Pre-Raphaelites.

Like Tolkein

and C.S. Lewis (both of them, by the way, scholars of medieval and Arthurian

literature), Geoffrey had hit on a popular form of serious entertainment which,

as one modern commentator has remarked, `in our postmodernist world is the

best any of us historians can hope to provide'. And, of course, it is true that

if it were submitted as a script for a cinema film or a TV drama serial now,

Geoffrey's book would be a lot easier to sell than Bede's providential tale, so

conspicuously lacking in irony. It is dazzling `infotainment' - much more

exciting than mere historical fact - and not surprisingly it reached a bigger

audience than other books of the time, just as books on the Holy Grail, the

Lost Ark and Da Vinci's code do better today than more sober histories.

The H.Grail

So as we have seen so far, by the

thirteenth century Arthur had become a pan-British hero. Sites associated with

him were pointed out from Scotland to Cornwall, and the poems known as the

Welsh Triads asserted that he had held his courts in Cornwall, Wales and

Scotland. Geoffrey's tale had turned him into a historical person, and it was

only a matter of time before someone tried to find him - especially in a

climate where political radicals and terrorists claimed that he would rise

again and drive the English out. This was what led to the search for his grave.

Various burial places of Arthur existed

in folk tales and local legends up and down the country. Geoffrey had named

Avalon as the place where the wounded Arthur was taken after the fateful last

battle of Camlann. In Welsh and Irish myth, Avalon,

the Isle of Apples, is an earthly paradise, the land on `the other side'.

Geoffrey did not identify it with any specific place - but it was only a small

step to do so. Within a few years of Geoffrey's book the idea arose that Avalon

was Glastonbury, and it was there in 1191, in perhaps Britain's earliest

recorded archaeological dig, that Arthur's tomb was `discovered'.

Almost as in a police investigation, the

monks conducted their dig behind screens to keep out prying eyes, between two

old Saxon stone crosses in the abbey cemetery. The chronicler Gerald of Wales

says that the place had been revealed `by strange and miraculous signs'. Monks

had had nocturnal visions, and there were even stories that King Henry II

himself had ordered the exhumation, having apparently acquired secret

information from `an ancient Welsh bard, a singer of the past', who said that

they would find the body at least 16 feet (5 metres)

beneath the earth, not in a tomb of stone but in a hollowed oak: `And the

reason why the body was placed so deep and hidden away is this: that 'it might

never be discovered by the Saxons, who occupied the island after his death,

whom he had so often in his life defeated and almost utterly destroyed ...'

Sure enough, about 5 metres

down, in a hollowed oak, they found the body of a big man and the bones of a

woman with him ... and a lead cross, engraved with the inscription: `Here lies

buried the renowned King Arthur, with Guinevere his second wife, in the Isle of

Avalon.'

With Arthur's rapidly growing status as

folk hero, tourist draw and political rallying cry, it was perhaps inevitable

that the English establishment should have wanted to find him. That way they

could hit at least two birds with one stone: both prove him dead, and reinvent

him as a tourist object. The discovery of the grave in 1191 also took place,

coincidentally or not, after a fire had badly damaged the abbey. The

restoration fund needed a boost, and finding the burial place at Glastonbury

provided it. As businessmen, medieval abbots were nothing if not pragmatic.

But could the Glastonbury skeleton

really have been Arthur? Some modern historians have argued that it was. Sadly,

however, the evidence is against them. The lead cross has since disappeared,

but it was illustrated by the antiquarian Camden in 1695, and to judge by the

letter forms in his engraving it was made in the twelfth century. The

references in the inscription to `King Arthur' and to Geoffrey's `Isle of

Avalon' point the same way. Moreover, modern re-excavation of the area located

the hole dug in 1191, and revealed the remains of two or three slab-lined

graves at the bottom, dating from the seventh century. The monks, one guesses,

had simply dug up one of their predecessors.

Although the 1191 exhumation was a fake,

it marks the appropriation of Arthur and Guinevere by the English. With hymns

and prayers, Arthur's bones would later be reburied inside the abbey in a

costly black marble shrine before the altar, in the presence of Edward I and

Queen Eleanor, like the holiest of sacred relics. From this time on he would

gradually cease to be a Welsh rallying cry - other heroes, more firmly based in

historical reality, such as Llewellyn the Great or Owain Glyndower,

would take his place. Meanwhile the exhumation only accelerated the spread of

Arthur's cult, which became all-pervasive from the late twelfth century

onwards. Indeed, the next phase of Arthur's tale moves to the Continent.

Arthur's French connection began soon

after the Norman Conquest. In the twelfth century a renaissance took place in

western Europe, driven on the one hand by the political power of the English

kingdom (a French-speaking kingdom of course) and on the other by the cultural

power of France. This is symbolized in the marriage of Henry II of England and

the vivacious and beautiful Eleanor of Aquitaine, the divorced wife of Louis

VII of France and mother of Richard the Lionheart. In this heady atmosphere

poets and troubadours transformed the Arthur legend from a political fable to a

tale of chivalric romance. The most powerful of the new twists given to the

tale at this time came from French writers. Most important among these was

Chrétien de Troyes, who worked for Eleanor's daughter Marie de Champagne. It

would be Chrétien who turned the legend from courtly romance into spiritual

quest.

Chrétien wrote several tales of Arthur

and his knights, but in the last one, written in around 1190 and left

unfinished at his death, he introduced a new and wonderful element. The knight

Perceval, young and inexperienced, is wandering in an unknown land ravaged by

war. Searching for shelter for the night, he enters a magical castle ('from

here to Beirut you would not have found a more handsome one,' writes Chrétien).

The castle is unprotected and its mysterious lord is wounded. Told to sit back

and watch, Perceval then sees a haunting vision:

A boy came in holding a white lance by

the middle of the shaft, and he passed in front of the fire. Everyone in the

hall saw the white lance with its white head, as a drop of blood issued from

the tip of the lance's head, and the red drop ran right down to the boy's hand.

Then two other boys appeared bearing candlesticks of the finest gold inlaid

with black enamel. In each one burned ten candles at the very least. Now a girl

came in, fair and comely and beautifully adorned, and between her hands she held

a grail. And when she carried the grail in, the hall was suffused by a light so

brilliant that the candles lost their brightness as do the moon or stars when

the sun rises. After her came another girl bearing a silver trencher. The grail

was made of the finest pure gold, and in it were set precious stones of many

kinds, the richest and most precious in the earth. or the sea.

Perceval is desperate to know the

meaning of the vision, `who was served from the grail', but earlier in his

adventure he was warned by an old knight not to talk too much, and he holds his

tongue.

But Perceval never learns the answer to

his questions. Very likely we will never know what Chrétien meant by the

strange vision. There are vague suggestions in his tale that the land of the

grail is ravaged by war and injustice, and that human suffering will continue

so long as humankind fails to act with the highest moral courage. But it is

Chrétien's vision of the grail itself that captured the imagination of every

writer after him. Even though his grail is pictured as a shallow serving dish,

later poets made it the cup used by Jesus at the last supper, sometimes elided

with the cup in which Mary Magdalene collected his blood at the crucifixion.

For the next three centuries this idea fired thinkers and poets across Europe,

giving birth on the way to the Glastonbury legends, and the fabulous tales of

the great German epics - Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzifal and Albrecht von Sharfenberg's Titurel. These in

turn inspired Wagner's Parsifal and such strange by-products as the Nazis'

grail castle at Wewelsburg, not to mention-one of

Hollywood's biggest grossing films of all time, Indiana Jones and the Last

Crusade.

So with Chrétien the idea of the Holy

Grail was born. Chrétien's image of the grail, luminous and other-worldly,

became a mystical symbol of all human quests, of the human yearning for

something beyond, infinitely desirable and yet ultimately unattainable. And

with that the Arthur legend enters the true realm of myth.

Chrétien's tales caught the imagination

of his age. And with the idea of the quest came the idea of the knighthood -

and the Round Table. Other writers now created full-scale literary versions of

the myth, sometimes with fabulous embellishments. Of these Robert de Boron was

the first to mention the Round Table, which now became the structuring

metaphor: binding together the disparate `histories' of the legend, and

symbolizing both high-minded fellowship and tragically flawed chivalric order -

as well as the ambiguous majesty of kingship itself. The table is depicted in

thirteenth-century art rather like the table of the Last Supper, part of the

progressive Christianizing of the story after Chrétien. Such tales proliferated

in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, clearly responding to a

psychological need in the courtly audience, and they spawned Arthurian relics:

the Winchester Round Table, for example, the most magnificent Arthurian relic,

was originally created for King into English and added his own mournful

commentary on the death of the Age of Chivalry. Born soon after Agincourt, he

had fought in the Hundred Years War in his teens and seen the collapse of

English power in Europe. He had also seen the failure of rulership at first

hand in the Wars of the Roses. These concerns were mirrored, as always, in the

Arthurian tale. Malory's Death of Arthur is a haunting vision of a knightly

golden age swept away by civil strife and the betrayal of its ideals.

Malory's was one of the first books

printed in English by Caxton in 1486. Malory identified Winchester as Camelot,

and it was there in the same year that Henry VII's eldest son was baptized as

Prince Arthur, to herald the new age. The young prince did not live to be

crowned King Arthur and usher in a true new Arthurian age, but his younger

brother became Henry VIII and took in the message. He had the Winchester Round

Table repainted, with himself depicted at the top as a latter-day Arthur, a

Christian emperor and head of a new British empire, with claims once more to

European glory, just as Malory and Geoffrey of Monmouth had described.

England was a Catholic medieval state,

of course, when Henry had his Round Table painted. A few years later the old

world of medieval Christianity in Britain was wiped away in the Protestant

Reformation. Glastonbury Abbey was plundered, the tomb of Arthur and Guinevere

was smashed and its contents were thrown to the winds. The last abbot was

dragged from the abbey on a hurdle and hanged on the Tor. So, even as the

Tudors claimed to restore the old British monarchy, they were to sever Britain

from its Catholic past, and in a sense from its imaginative past, its cultural

roots. With Henry's Reformation the old spirit world was erased, and with it

much of the fabric of language, symbols and social ideals that had given birth

to the Arthurian legends of the high Middle Ages.

But even if the medieval myth had lost

its spiritual basis, it was to enjoy many and varied afterlives in Tudor times,

especially as a political fable. The Arthurian myth was revived most famously

in Edward Spenser's The Faerie Queene, when, in a curious transformation,

Elizabeth's mythical descent from the ancient Britons and King Arthur was

presented as a Protestant imperial myth, with a pure knighthood obeying the

commands of a Virgin Queen and spreading the light of her rule through the

world. In the same way her kinsman and successor James I, in uniting the crowns

of England and Scotland, would present himself as a new Arthur of Britain. And

so, in a curious and roundabout way, the ancient prophecies of Geoffrey of

Monmouth had come to pass.

All that, of course, was a fantasy of

the ruling class. With revolution, regicide and the Protestant settlement in

the seventeenth century, it might be thought that the legend had run its course

as a myth central to the needs of political and literary culture in Britain.

Indeed, the tale did lose its popularity in the seventeenth century, but great

myths that have been built up over hundreds of years don't just disappear. They

last because their themes respond to something deep in the minds of their audience,

and in the early eighteenth century a funny thing happened.

At the Fountain Coffee House in the

Strand in 1720 a group of literary gentlemen founded the Honourable

Society of the Knights of the Round Table. In fact, it was claimed at the time

that it was a 'refoundation', and that the society really went back to before

the battle of Crécy in 1346. Be that as it may, the society is still in

existence and still meets on the site of the Fountain, now Simpsons in the

Strand. Its goal was the `perpetuation of the name and fame of King Arthur of

Britain and the ideals for which he stood', including `his Christian endeavour and beliefs'. The society, as it turned out, was

the precursor of the nineteenth-century rebirth of Arthur.

As we have already seen in this story,

the legend was often re-created in times of crisis and change. At the turn of

the nineteenth century, modernity and industrial revolution were on the

horizon. There was also a questioning of the past, especially of the old

spiritual traditions of Britain and the loss of the pre-Reformation Catholic

past. Through the myth, and the rediscovery of the sacred art of the Middle

Ages, nineteenth-century people were attempting to renew contact with the world

from which they had been irretrievably separated by the Reformation.

The rebirth of Arthur owed a great deal

to the rediscovery of Malory's book, which had a tremendous impact when it was

republished in several editions in the years after 1800. The perennial vitality

of the legend worked its magic again. Its compelling themes struck modern

people in the same way that they had thirteenth-century listeners and readers:

the quest, the pure knighthood, the fatal union of adulterous love, the deep

pathos of civil strife and the ambiguous majesty of kingship itself. All these themes

would have a powerful appeal for the Victorians.

Thus in the early nineteenth century an

Arthurian revival began which was as fervent in its way - and as brilliant - as

that in the thirteenth century. When the Houses of Parliament were rebuilt

after the disastrous fire of 1834, Arthurian themes from Malory's book were

chosen for the decoration of the queen's robing room in the House of Lords, the

symbolic centre of the British empire. The plan had

the enthusiastic support of Prince Albert himself, although the theme of

Guinevere's adultery was thought inappropriate, and the Holy Grail itself was

carefully kept out of sight as `a matter of religious controversy best

avoided'. Roman Catholics had only recently been allowed to practise

their religion freely, and it was felt that when the queen, the head of the

Church of England, was dressing for the highest state occasions, her thoughts

were best not distracted by Malory's theological - and very Catholic -

interpretation of the grail.

Nevertheless the Victorians were

irresistibly drawn to the mystical quasi-religious power of the Arthurian tale.

Poems such as Tennyson's Idylls of the King and William Morris's The Defence of Guinevere, perhaps the greatest Victorian

literary treatment of the subject, are testaments to an obsession that runs

through their art, poetry and sculpture. It is seen in the fantastically

powerful re-creations of the legend by the Pre-Raphaelite painters; and even in

the new medium of photography where Julia Margaret Cameron's haunting

compositions are a key Victorian visual imagining that has shaped our

sensibility and our versions of the tale right down to silent movies and modern

Hollywood. Boorman's Excalibur, Bresson's Lancelot and Sean Connery in First

Knight are all her children.

The Victorian Arthurian legends were

both an _expression of pan-British identity - Celtic and Saxon united - and a

nostalgic commentary on a lost spirit world. The fragility of goodness, the

burden of rule and the impermanence of empire (a deep psychological strain,

this, in the whole of nineteenth-century British literary culture) were all

resonant themes for the modern British imperialist knights, and gentlemen, on

their own road to Camelot. To which one might also add the weird feminization

of Arthur in Victoria's empire. Strange as it may seem, as with Elizabeth I the

widow of Windsor was in some sense Arthur reborn.

And there you might have thought the

story of the legend and its many transformations ends. But the Victorian Arthur

is not quite the last chapter of the story. For the latest phase of the

invention of Arthur is our own. The late twentieth century became one of the

greatest of all eras of Arthurian invention. The recent flood of books, films

and pictures is a testimony no doubt to the remarkable vitality of the legend,

but also to a new twist in the tale: archaeology.

Archaeology arose as a science in the

late nineteenth century, when its popular appeal was closely tied to the

astonishing discoveries by Heinrich Schliemann in Greece and Turkey, which

suggested that behind the myths and legends of Troy there was real history. In

our own time British archaeologists set out to find the real Arthur, just as

the Glastonbury monks did in 1191. The result was predictably similar. The

places chosen for excavation are familiar ones in our tale: Glastonbury, the

`Isle of Avalon'; Cadbury Castle in Somerset, an Iron Age fort which had been

claimed as Camelot by Henry VIII's antiquarian John Leland; Tintagel, Arthur's

birthplace in Geoffrey of Monmouth's version. In all these places enough clues

were found - feasting halls, earthen defences,

monastic settlements - to conjure up a convincing Dark Age reality. At Dinas

Emrys in Wales excavators even located the pool where, according to Geoffrey of

Monmouth, vessels were found containing the two dragons in Merlin's prophecy.

Sticking to their sources, nit-picking textual scholars pointed out that none

of this proved the existence of Arthur. By now, however, I dare say the idea of

the historical Arthur is fixed. Today films, programmes

and books about the `real' Arthur appear every year. In terms of heritage,

history and myth, his is the biggest publishing business in Britain.

Ironically, then, it is we moderns who have turned the tale into fact. Arthur

has finally become real history. How Geoffrey of Monmouth would have laughed!

Meanwhile, as twentieth-century

archaeology attempted to find a real world of Arthur in the ground, other

discoveries were being made that cast the process of the creation of such myths

in an entirely different light. Answers were being sought not in archaeological

strata, or in documentary texts, but in the nature of storytelling itself.

Modern recording of oral tale-tellers in different parts of the world has

illuminated the way in which Bronze Age stories like that of Troy came down to

bards such as Homer in the Iron Age. They show that behind a written text can

lie a story shaped over many centuries by oral transmission. These discoveries

have also opened up the deeper currents of Celtic story-telling.

In Ireland many ancient tales in the

Gaelic language that were written down in the Middle Ages offer close parallels

to the Arthur stories. Finn Macool, for example is,

like Arthur, a leader of warriors, one of whom has an affair with Finn's wife,

`the white enchantress'; Finn's warriors seek a cup; their fellowship dissolves

after a last fatal battle - and Finn will also return one day. In Ireland too

are stories of magic cauldrons `which could deliver to any company its suitable

food', of a `victory bringing sword' and a fairy cup that `revealed all

falsehood'. Some of these tales come from a time before the great medieval

Arthurian romances, and recently it has become clear that some have been passed

down orally for many centuries.

The name appears as Artuir

in Irish and north British texts of the sub-Roman period. As it happens, in the

Life of St Columba written by Adomnan of Iona in around AD 700, there is an

undoubted Arthur, unmediated by the fakers, con men and myth-makers, in an

authentic early manuscript. The tale in which he appears takes us full circle:

back to the wars of the fifth and sixth centuries described by Gildas ... but

it is a different tale, and in a different place.

He was Artuir,

eldest son of Aedan mac Gabrain, King of Dalriada,

the Scottish Dark Age kingdom situated in the Clyde valley. This was a Gaelicspeaking kingdom founded by immigrant tribes from

Ireland earlier in the sixth century. Now this Arthur died tragically with one

of his brothers in a battle in the 580s or 590s where they defeated an obscure

border tribe called the Miathi. The prince's death

was remembered, and in Irish annals too because it was the subject of a

prophecy by St Columba, which is why the tale is told in his biography.

Artuir fought and died in an area well known to Arthur

specialists: the lands between the Firth of Forth and Hadrian's Wall, where we

know sub-Roman warlords continued to hold power long into the Dark Ages. Now

this region is also where the earliest Old Welsh poetry comes from: the poems

of the bards Aneirin, Taliesin and, interestingly enough, Myrddin, `the Wild',

the wandering fugitive whom Geoffrey of Monmouth turned into Merlin. As we

might expect, some of the battles preserved in the bardic tradition go back to

this place and time, among them Aneirin's famous poem the Gododdin,

about the raid on Catterick. The battles remembered by the bards were not all

against the Saxons, though; some were against Picts, Scots and Cumbrians. This

has been a lawless region fought over throughout history: cattle rustlers,

border raiders, war-bands and their leaders have been the subject of songs and

stories for centuries. Perhaps this is the kind of context in which a bard in

the court of Dalriada might have sung of the victorious but tragic battle

prophesied by St Columba, where King Aedan's heir Artuir

died fighting with his brothers and 303 heroes of his war-band?

There is one final clue in this north

British connection. In the Annals of Wales, as we saw earlier, Arthur's last

battle took place at a place called Camlann. If this

name is represented by any surviving Roman place-name, scholars agree it is the

fort of Camboglanna on Hadrian's Wall at Castlesteads, by the river Irthing

east of Carlisle. The fort lies south of the Caledonian forest and only a few kilometres from Arthuret, where

another famous battle in 573 involved Myrddin, the prototype of Merlin. So why

did the tradition name Camlann as Arthur's death

place?

In the forests by Hadrian's Wall is a

swift-flowing stream with leaping salmon: a tributary of the Irthing rushes through a winding glen. The steep hillside

above is covered with trees, now turning to autumn gold, yellow and brown. The

name of the stream is Cam Beck, perhaps preserving the first part of the

ancient Roman name. A long, secluded drive leads through the woods to a fine

eighteenth-century house, hidden in the forest. Walk on along a muddy path

through the woods and soon, under the tangled trees, you make out traces of the

embankments of a Roman fort, just visible under thick undergrowth and the

remains of an eighteenth-century landscaped garden. In an old potting shed,

behind a wooden wheelbarrow and a watering can, is a row of Roman altars and

statues, bearing inscriptions to Roman and British gods and goddesses:

goddesses of nature and of the forests, Hercules, and Cocidius, the Celtic

Mars, all cut in the pinkish sandstone from which the fort was built. A civil

settlement, probably still inhabited in the sixth century, lies in the fields

below. That was when a nearby fort on the Wall at Birdoswald

sheltered a spectacular wooden hall, where some unknown British warlord and his

warrior band washed their spears and feasted in the sub-Roman twilight.

Walk on through the woods and you come

to a steep drop over a sharp curve of Cam Beck: this is the `crooked bank' (camboglanna), which gave the fort its name. From a little

wooden footbridge over the stream you can see the weir where Hadrian's Wall

crossed the beck. So was this Arthur's Camlann?

The early Welsh poems allow us to imagine

the real world of Dark Age British leaders in their feasting halls. They wore

golden torcs, or necklaces, and cloaks of beaverskin;

they drank `pale mead' from gilded cups; they fought with `stained swords and

bristling spears', and boasted, so the poets said, that they would `rather be

flesh for wolves than go to the altar to wed'. Leading their mounted war-bands

they rode long distances to do battle, like the three hundred heroes killed at

Catterick whose praises were later sung in the royal halls of `the men of the

north'; or the Cumbrian host of Urien of Rheged who

blockaded the Saxons at Lindisfarne in 575. Was this how it was for another

young prince who battled valiantly in the Caledonian forest in the heroic age

of Celtic Britain? That, for what it is worth, is my hunch about the

`historical kernel', if such there was. If so, it was small compared with all

that followed. Perhaps nothing but the name.

Arthur, we take it then, is essentially

a mythical character, like the sleeping hero of Irish legend: one focus of the

millennial hopes of the British in the Dark Ages. Stories involving other

mythical and historical characters may have become attached to his name in the

eighth and ninth centuries, as the English pushed west. By the ninth century

Arthur was certainly a figure of legend, although the Arthur we know and love

is the literary creation of Norman and post-Norman writers, the collective work

of Geoffrey of Monmouth, Chrétien de Troyes and the rest. His story is a body

of myths gathered over 1500 years, some of whose themes and motifs go back into

the Iron Age.

The figure of Arthur in the end became a

symbol of British history, a living link between the Matter of Britain and the

Matter of England. Seen that way, the myth also became a way of exorcizing

ghosts and healing the wounds of history - some of which, as we know from

conflicts in our own time, can be very long-lasting. In such cases the dry,

historical fact offers no solace, prey as it is to the power of the winners.

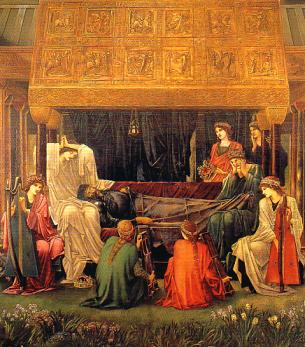

Below Arthur in Avalon (1881), part of

the canvas by Burne Jones, one of many powerful Victorian reinventions of the

tale.

For updates

click homepage here