By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

Montevideo And The Geneva Conventions

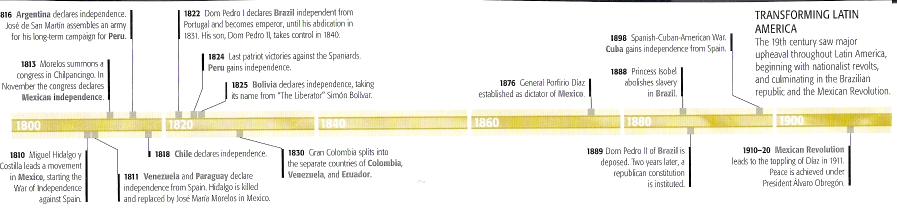

In order to

understand state formations in the modern era (like we illustrate underneath) one

has to learn about the Montevideo Conference.

A state is an

association of a considerable number of men living within a definite territory,

constituted in fact as a political society and subject to the supreme authority

of a sovereign..1This definition written in 1918 is one of the many antecedents

to one of the important Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of

States of 1933 the only time in history that states decided to commit to a

select criterion to provide a definition of a state. Surprisingly, the

literature surrounding this event is rather scarce. There is hardly any

evidence indicating why there was a need to codify statehood at that particular

moment in history. Furthermore there is no evidence of why the four criteria

were chosen for the definition of statehood and why the states insisted on

these particular criteria. There is also no record of how the criterion was

chosen and whether there were discussions or disagreements pertaining to it or

whether it was chosen unanimously.2 British statesmen and legal scholars were

the first to formulate the principles for the recognition of newly independent

states. This was largely due to the necessity of dealing with the emancipation

of the Latin America republic and their establishment as independent states.3

"The attempt of the great powers of Central and Eastern Europe to restore

a European law of nations on the basis of a substantive principle of legitimate

government was driven back to the view that new states and governments could

only be recognized after a careful scrutiny of the lawfulness of the new

states' formation and constitution.4

Recognition had to be

refused if either the process of formation or the constitution were illegal or

contrary to a claim of sovereign rights by the mother country. The official

attitude of the British and American governments has been to regard recognition

as an acknowledgment of facts. It was a declaration that a foreign community

had acquired the qualifications of statehood and is willing to enter into the

community of states. The revolt of the Spanish colonies, although not the first

case in which the question of recognition had occurred, was the most important

occasion for the formation of the Anglo-American practice on this subject. The

spark of the independence movement in Latin America started with the French

invasion of Spain in 1808. The loyal 'juntas' originally formed in the American

Colonies in support of the Spanish Regency against the French invaders, were

soon transformed into a number of separatist movements. The liberation of the

Latin American States represented one of the most important cases of

recognition in the nineteenth century. It signified a defeat of the principles

advanced by the Holy Alliance and a victory for those advocated by Britain and

the United States. In March 1822 the United States recognized the United

Provinces of Rio de la Plata, Columbia, Chile and Mexico, and followed up with

the exchanges of envoys. Two years later, Britain followed suit. Spanish

protests at the time against these actions were based on the argument that

Spain had not definitely lost effective control over these countries.5 The

emergence of independent South American states resulted in the formulation of

two important principles relating to recognition. First, Britain on the

initiative of its Foreign Secretary, George Canning, made it clear to Brazil and

Mexico that it viewed the abolition of the slave trade as a pre-condition for

recognition. Recognition therefore, served as a policy tool providing

incentives to countries and in a sense, forcing them to abide by international

standards set in place. Secondly, since the process of decolonization and

recognition of new states carried with itself the danger of states entering

conflict over border issues, the South American States adopted the principle of

uti possidetis, ensuring that the colonial borders

were honored by the newly independent States. By acquiescing to this principle

they prevented a significant number of territorial disputes. There have been

other examples of additional conditions imposed on countries prior to their

recognition. Lord Canning, one of the most prominent diplomats in Britain in

his course of negotiations with the Latin American republics, introduced

humanitarian considerations into the recognition of states by formulating four

conditions for recognition. He stated that Britain would recognize a country if

its government: had notified its independence by public acts; possessed the

whole country; had reasonable consistency and stability; and had abolished the

slave trade.6

It was clear that due

to a lack of universal standards for recognition of new states, great powers

themselves determined criteria which they used to establish which states

qualified for recognition. As British requirements clearly demonstrated some of

the conditions were extremely vague and open for interpretation by the

recognizing country. The requirement of "reasonable consistency and

stability" is a prime example of the extent to which recognition and its

requirements were subjective. This was implemented more as a strategy to create

leverage for powerful states to control not only which countries were

recognized but also the timing of recognition i.e. recognizing powers giving

themselves the authority to determine at which point in time the conditions in

the country were considered 'consistent' and · stable' Overall, one of the most significant changes

that took place with respect to recognition was the fact that recognition no

longer signified admission into the Christian European family of nations. Therefore,

the prerequisite for acquiring "full international legal and

representative capacity was no longer the cultural or religiously-based sense

of belonging to the Christian European family of nations as had been presumed

in respect of the United States by the French act of recognition of 1778.“7

Now the main

requirement was development of a nation to a certain degree of civilization,

abolition of slave trade being the main requirement. The importance of this new

foundation of the international legal order did not become visible untillater.8

However, it impacted the way aspiring states developed and the policies they

implemented. With the emancipation of Latin American State, one of the most

important undertakings for the United States and the whole region of Latin

America was to establish mechanisms for promoting peace on the American

continent. Similarly to the great powers in Europe perceiving themselves as the

guardians of peace in Europe, the United States viewed its role as ensuring

peace and unity in Latin America. Ideas of Pan American cooperation are as

old as the birth of the Latin American republics. A feeling of unity among

these 'states', based on race, language and similar cultural and political

heritage, was enhanced by the fear that Spain would attempt to regain its

American colonies. The colonies realized that only security and political

cooperation would make their continent safe for their future development as

independent states.9

Latin American

countries began organizing conferences and forming alliances for defense

against foreign invasion and the peaceful settlement of inter-American

disputes. The aim of these meetings was to develop closer political ties

between the American countries and most of the proposals were political in

nature. In 1877 a Congress of Jurists representing nine Spanish-American

countries assembled at Lima to discuss the unification of private international

law 10 Soon thereafter the United States initiated conferences with Latin

American countries advocating more involvement. Both Latin America and the

United States recognized that only by imposing agreements that were both legal

and political would they achieve lasting and stable conditions. James G. Blaine,

the U.S. Secretary of State, in his invitation of 1881 for a conference of the

American states defined the purpose for the meeting to discuss methods of

preventing war between the nations of America. This aim was also stressed by

the United States Congress in 1882 when it requested the President to call a

conference of the republics on the continent for the purpose of

"discussing and recommending for adoption to their respective Governments

some plan of arbitration for the settlement of disagreements and disputes that

may hereafter arise between them.“11

In 1888 a bill

authorizing the holding of a Pan-American conference passed both Houses of

Congress and received the approval of President Cleveland. An invitation was

extended to several Governments of the Republic of Mexico, Central and South

America, Haiti, San Domingo and the Empire of Brazil to meet in Washington in

1889.Most of the items on the agenda of this First International Conference of

American States, dealt with commercial or economic matters. However the

conference did establish one of the mechanisms for peaceful dispute resolution.

It stated: "The Republics of North, Central, and South America hereby

adopt Arbitration as a principle of American International law for the

settlement of the differences, disputes or controversies that may arise between

two or more of them.“12 Another concrete achievement was the establishment of

the Commercial Bureau of the American Republics in Washington, an organization

which later became the Pan American Union.13

The Second

International Conference of American States met at the initiation of President

McKinley in 1889 and was held in Mexico from 1901 until 1902. At this

conference, the same types of questions were considered as at the First

Conference. One result of this conference was a protocol in which the American

republics recognized as a part of "Public International American

Law", the principles of the First Hague Conference 14 for the pacific

settlement of international disputes. A number of the Latin American states

signed a treaty on compulsory arbitration and the representatives of seventeen

countries, including the United States, signed a treaty for the

"Arbitration of Pecuniary Claims".15 The Third International

Conference of American States, held in Rio de Janeiro in 1906, adopted a

resolution "to ratify adherence to the principle of arbitration; and to

recommend to the Nations represented at this Conference that instructions be

given to their Delegates to the Second Conference to be held at The Hague, to

endeavor to secure by the said Assembly the celebration of a General

Arbitration Convention." Significantly, a Convention on International Law

was also adopted, and the International Commission of Jurists provided for in

this agreement held its first meeting in Rio de Janeiro in 1912. This was the

beginning of the efforts to advance peaceful international relations by the

gradual codification of international law. At the time many Latin American

countries felt that political agreements could only make a limited contribution

to countries abiding by signed commitments. They perceived that only legal

standards could make a lasting impact on state practices. One of the primary

concerns of the Latin American countries was the question of intervention by

the United States into the affairs of Latin American countries. This issue was

especially debated at the Havana and Montevideo conferences.16

Along with

efforts towards codification, the treaty signed in Washington D.C. on December

20, 1907 by Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and EI Salvador

established the first permanent International Court of Justice.17

Unfortunately, due to political events and turmoil, it went out of existence.

This effort pointed to the fact that the Latin American countries and the

United States were undoubtedly moving in the direction of establishing norms

and promoting the development of international law. The development of new

standards and regulations as prescribed by international law rather than

politics only, was perceived as a clear indication that the conferences were

making a lasting and more profound contribution to peaceful co-existence of

nations. Another development at the time was the fact that countries began to

rely on international courts for peaceful resolution of conflict. The Fourth

International Conference of American States meeting at Buenos Aires in 1910

adopted a general claims convention providing for the submission of claims to

the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague, unless both parties agreed to

constitute a special jurisdiction.18

The promise for world

peace then emanating from The Hague undoubtedly made it appear less necessary

for the American republics to take further action. This new change clearly

showed countries' desire to develop international standards and universal codes

supported by international institutions that would ensure that international

law principles were upheld. New developments, which took place in the field of

international relations between 1910 and 1923, gave the development of American

peace machinery a new incentive. Several factors during this period aided the

program of Pan-Americanism. When the United States accepted the mediation of

the ABC powers (Argentina, Brazil and Chile) in its dispute with Mexico and

joined these countries in a meeting at Niagara, there was profound satisfaction

in Latin America. Comments in the press of both North and South America were

unanimously favorable, and the other members of the Pan American Union

supported the idea of joint mediation.19 The Latin American countries perceived

it as a clear indication that the United States was willing to abandon

intervention for more diplomatic efforts such as negotiations. At the Santiago

conference in 1923 the most decisive step toward the establishment of definite

and far-reaching peace machinery was made through the adoption of the

"Treaty to Avoid or Prevent Conflicts between the American States",

also known as Gondra Treaty. The treaty was

significant because for the first time a Commission of Inquiry was established.

Even though there had been previous attempts to develop such a commission, 279

the Gondra Treaty 20 went much further and attempted

to develop a permanent commission that might be called into action whenever a

dispute arose or there was danger of conflict in international relations.21

Moreover, the Gondra Treaty set up two diplomatic commissions one in

Washington and the other at Montevideo. They were made up of three senior

diplomatic representatives of American states and were entrusted with the

appointment of the specific commissions that would serve as agents of inquiry

whenever a controversy or dispute arose between two or more states, acting on

the request of any signatory state. Along with dispute resolution mechanisms,

before any further advancement could be made in the sphere of international

law, it became apparent that there was a need to establish a sense of equality

among states. This affirmation was necessary in order to establish firm legal

principles. The American Institute of International Law while doing preparatory

work for the International Conferences of American States, restated in 1924 a

fundamental principle which it had already established on January 6, 1916, in

its Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Nations: "Every nation is in

law and before the law the equal of every other nation belonging to the society

of nations, and all nations have the right to claim and, according to the

Declaration of Independence of the United States, 'to assume, among the Powers

of the Earth, the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and of

nature's God entitle them.22 In the project of a convention on

"Nations" which the institute submitted to the Pan American Union in

1925 for the consideration of the International Commission of Jurists23 at its

meeting in Rio de Janeiro, article 2 read: "Nations are legally equal. The

rights of each do not depend upon the power at its command to insure their

exercise. Nations enjoy equal rights and equal capacity to exercise them.“24

The Rio de Janeiro Commission of Jurists, composed of members officially

appointed by all the American Republics, added to this article, in its 1927

meeting, an even more radical form: "States are legally equal; enjoy equal

rights and have equal capacity to exercise them. The rights of each State do not

depend upon the power at its command to insure their exercise but only upon the

fact of their existence as personalities in international law.“25 The

International Commission of Jurists met in Rio de Janeiro in 1927 and submitted

to the Havana Conference twelve projects on public international law and a code

of private international law. One of the projects relating to the rights and

duties of states included the phrase: "No state may intervene in the

internal affairs ofanother".26

This concept of

non-intervention was to become one of the central topics during all

conferences. The unfavorable conditions surrounding the Sixth Conference or

Havana Conference in 1928 due mainly to the aloofhess

of certain states like Argentina and the suspicions and resentments that

occupation of Nicaragua by the United States Marines had aroused, prevented any

further developments in the maintenance of peace. However the Washington

Conference of American States on Conciliation and Arbitration still met in

Washington from December 10, 1928 to January 5, 1929 and adopted a resolution

condemning war as an instrument of national policy.27 The American republics,

at this conference, expressed the "most fervent desire" to contribute

"in every possible manner to the development of international means for

the pacific settlement of conflicts between States" and resolving that

"the American Republics adopt obligatory arbitration as the means which

they will employ for the pacific solution of their international differences of

a juridical character.“28 The Conference also adopted a General Convention of

InterAmerican Conciliation by which the parties agreed to submit to the

procedure of conciliation all controversies which have arisen between them for

any reason and which it may not have been possible to settle through diplomatic

channels. This convention in addition gave the commissions of inquiry

established by the Gondra Treaty the character of

commissions on conciliation as well as inquiry. The Conference adopted a

"General Treaty of Inter-American Arbitration" by which the parties

"bind themselves to submit to arbitration disputes that arise between

them. Moreover, the Conference adopted a "Protocol of Progressive

Arbitration" by which any party to the General Treaty may at any time

deposit with the Department of State "an appropriate instrument evidencing

that it has abandoned in whole or in part the exceptions from arbitration

stipulated in the treaty. The Convention was ratified by fourteen of the

twenty-one American Republics and the General Treaty and Protocol by twelve.29

The United States

signed the arbitration treaty on January 19, 1932 subject to the reservation

that the treaty should not be applicable to disputes arising out of previously

negotiated treaties.30 Another important development was the Treaty for the

Renunciation of War, known as the Pact of Paris which was adhered to by all of

the Latin-American states, with the exception of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, El

Salvador, and Uruguay. Of these, Bolivia, EI Salvador, and Uruguay expressed an

intention to abide by it, while Argentina agreed to adhere in exchange for the

signature of the United State to the Argentine Anti-War Pact, an agreement

informally negotiated at the Montevideo Conference of 1933. In addition, every

Latin American republic with the exception of Ecuador became a member of the

League of Nations. The Washington Conference was one of the most important

meetings in modem history for the promotion of peace machinery and the

outlawing ofwar.31

However, lacking

measures of enforcement, it achieved very little and left Latin American states

insecure about their future with respect to intervention and security. At the

beginning of the twentieth century, the Americas were again the focus of developments

in recognition policy. Recognition or refusal to recognize revolutionary

regimes was seen as a political tool in providing incentives to governments to

abide by conventions and agreements. Both President Wilson's policy

of"constitutionalism“32 and the Tobar doctrine,33 contained in Latin

American conventions of 1907 and 1923,34 sought to protect constitutional govenunents against revolution by threatening revolutionary

regimes with non-recognition. Recognition was widely construed as intervention

in the internal affairs of States, and was not able to withstand its rival, the

Estrada doctrine35 of 1930. Latin American countries promoted the Tobar

Doctrine which provided that: "The American Republics for the sake of

their good name and credit, apart from other humanitarian or altruistic

considerations, should not intervene in the internal dissensions of the

Republics of the Continent. Such intervention might consist at least in the

non-recognition of de facto, revolutionary governments created contrary to the

constitution.“36 It is clear that both Wilson and Tobar were motivated largely

by considerations of humanity and respect for democratic institutions.37

The Tobar Doctrine

dominated the state practice of that period. This period was also characterized

by instability and uncertainty in Latin America. Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of

State in 1931 illustrated the intolerable situation in the Western Hemisphere

characterized by economic depression and unemployment, which brought

instability and unrest to many countries. In the short period of only few years

starting in March 1929, Latin America witnessed seven revolutions resulting in

the forcible overthrow of governments in six countries.38 Stimson addressed the

recognition policy of the United States towards new governments as well as the

sale and transportation of arms and munitions to the countries involved in the

strife. He referred to the Monroe Doctrine and clarified that it did not stand

for "suzerainty over our sister republics" but rather it represented

"an assertion of their individual rights as independent nations".39

It was a declaration that the independence of nations was vital to the safety

of the United States. With respect to recognition, Henry Stimson defined

recognition of a new state as the "assurance given to it that it will be

permitted to hold its place and rank in the character of an independent

political organism in the society of nations.“40 President Woodrow Wilson's

government sought to put this new policy into effect in respect to the

recognition of the then Government of Mexico headed by President Victoriano

Huerta. Although Huerta's government was in de facto possession, Wilson refused

to recognize it, and he sought through the influence and pressure of his office

to force it from power. Wilson's policy differed from his predecessors in

seeking actively to propagate the development of free constitutional

institutions among the people of Latin America.40

In 1907 five

republics of Central America: Guatemala, Honduras, Salvador, Nicaragua, and

Costa Rica were engulfed in conflict and their governments were under constant

revolutionary attacks. These countries met at the joint suggestion and

mediation of the governments of the United States and Mexico and agreed to the

following: "The Governments of the high contracting parties shall not

recognize any other government which may come into power in any of the five

republics as a consequence of a coup d' etat, or of a

revolution against the recognized government, so long as the freely elected

representatives of the people thereof, have not constitutionally reorganized

the country.“40 The policy of denying recognition to governments that were

formed by illegitimate means was followed in the case of Guatemala. On December

16, 1930 General Orellano, the leader of the revolt, set himself up as the

provisional president of the republic. On December 22, 1931, the United States

notified him that in accordance with the policy established by the 1923 treaty

he would not be recognized. Soon thereafter, Orellano resigned and retired from

office. On January 2, 1931 through the constitutional forms provided in the

Guatemalan Constitution, Senor Reina Andrade was chosen provisional president

by the Guatemalan Congress and immediately called a new election for a

permanent president. Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson pointed out that:

"since the adoption by Secretary Hughes, in 1923, of the policy of

recognition agreed upon by the five republics in their convention, not one

single revolutionary government has been able to maintain itself in those five

republics.“41

It was clear that the

Latin American countries and the United States have embarked on a road to

cooperation and that the agreements they achieved with respect to recognition

were being enforced. By the nineteenth century, the great powers were claiming

an international legal right to protect their nationals and their nationals'

property anywhere in the world, a right that could be pursued according

to a variety of means, from diplomacy to armed force. The legality of

intervention was first challenged by the Argentine diplomat and jurist Carlos

Calvo (1822-1906), who formulated what became known as the Calvo Doctrine.42

Its two core principles included the absolute right to freedom from

intervention, and the absolute equality of foreigners and nationals. Based on

the dismal Latin American experience with international intervention, Calvo

argued that the countries of Latin America were entitled to the same degree of

respect for their internal sovereignty as the US and the countries of Europe.43

He proposed that states should be free, within reason from interference in the

conduct of their domestic policy. Calvo's principles did live in the

"Calvo Clause", an attempt to implement the doctrine by including it

in contracts with foreigners. Calvo argued that foreign nationals could not lay

claim to greater protection in their disputes with sovereign states than the

citizens of those same countries. Foreign nationals who chose to establish

themselves within the territorial confines of the host state through direct investment,

for example, were entitled to no greater protection from state action than

those nationals residing within the acting state. These precepts came to be

reflected in the Mexican Constitution's Calvo Clause which prohibits foreign

investors from seeking the protection of their home state in any dispute with

the Mexican host state.44 His doctrine was transformed from a general legal

claim into a binding personal commitment, freely accepted by the signers of

contracts not to call on their own governments in cases of contractual

disputes.307 In the form of contractual clause Calvo's doctrine has been widely

implemented in Latin America, and some constitutions, such as that of Mexico,

even required it in contracts with foreigners. The greatest obstacle to

Pan-American cooperation was the Latin American policy of the United States.

This policy was based on the Monroe Doctrine 45, the meaning of which radically

changed during the century following its promulgation in 1823. At the beginning

the doctrine was regarded as an instrument for defense of the United States.

Under the doctrine the U.S. claimed the right to prevent acts of European

aggression on the American continents, but did not claim the right to control

the acts of Latin American states.45

President William

McKinley (1897-1901) had allegedly sought to avoid war with Spain when he was

elected in 1896. However a series of events, including the mysterious sinking

of the battleship U.S.S. Maine in a Cuban harbor on February 15, 1898, as well

as sensationalist newspaper reporting about Spanish atrocities against Cuban

insurgents, increased the popular pressure for U.S. intervention to liberate

Cuba from Spain. On April 11, 1898 McKinley asked Congress for authority to use

force against Spain to defend U.S. interests. Congress complied and on April

24, Spain declared war on the United States, which was followed by a

congressional declaration of war against Spain the next day.56 Following these

events Theodore Roosevelt's famous corollary to the Monroe Doctrine took on a

new interpretation. According to it, the United States was justified in

intervening in the internal affairs of the Latin American states not only to

protect its own interests, but also European interests in the hemisphere.

President Theodore Roosevelt pointed out that "the American continents are

...not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European

power. . . the Monroe Doctrine is a declaration that there must be no

territorial aggrandizement by any non-American power at the expense of any

American power on American soil.“57 Roosevelt added that "in case of

financial or other difficulties in weak Latin American countries, the United

States should attempt an adjustment there of lest European Governments should

intervene, and intervening should occupy territory.“58

An important step

towards non-intervention was taken by the United States in 1898 when it took

part in the Pacific Settlement Convention of the first of the Hague

Conferences. IN the first paragraph of Article 27 it provided: The signatory

Powers consider it their duty, if a serious dispute threatens to break out

between two or more of them, to remind these latter that the Permanent Court is

open to them.“58 The convention was signed by the delegation of the United

States, with a reservation to this article, and was advised and consented to by

the Senate, with the reservation stated as a part of the act of ratification:

"Nothing contained in this convention shall be so construed as to require

the United Stats of America to depart from its traditional policy of not

intruding upon, interfering with, or entangling itself in the political

questions of [or] policy or internal administration of any foreign state; nor

shall anything contained in the said convention be construed to imply a

relinquishment by the United States of America of its traditional attitude

towards purely American questions.“59

The Pacific

Settlement convention was ratified with this reservation by President McKinley

on April 7, 1900. The ratifications containing this reservation were deposited

on September 4, 1900 and the convention was proclaimed on November 1, 1901 by

President Theodore Roosevelt. Theodore Roosevelt in his 1902 message to the

Congress pointed out: "More and more, the increasing interdependence and

complexity of international political and economic relations render it

incumbent on all civilized and orderly powers to insist on the proper policing

of the world." m During his presidency, the United States thought of

itself as a protector utilizing both diplomatic and military means to safeguard

the territory of Latin America. The United States was willing to uphold the

promise of "non-interposition" to use the language of the Monroe

Doctrine or no "intervention" or "intermeddling" of any

kind in the internal or foreign affairs of the Latin American countries.60 It

literally became a sheriff for the Western Hemisphere or at least for those

countries in the close proximity to the Panama Canal.61 Examples of the new

policy were evident everywhere. It assisted in bringing the Republic of Panama

into existence in 1903 and in return Panama concluded a treaty with the United

States providing it with wide power of intervention in Panama and authorizing

it to construct an Americanized and militarized cana1.62

At the end of the

World War I a number of prominent Americans gave warning that because of the

Monroe Doctrine, the United States would not consent to the intervention of the

League of Nations in the Western Hemisphere. The fear of Latin Americans was increased

in 1921 when Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes appointed by the Coolidge

administration, sent a battleship and 400 marines to Panama for the purpose of

forcing it to turn over certain territory to Costa Rica, following an arbitral

award which Panama had protested as invalid.63 This was a clear indication that

the period of intervention was not over. When the Sixth International

Conference of American States convened in Havana from January 16 to February

20, 1928, U.S. troops were occupying Haiti and fighting a guerrilla war in

Nicaragua against the peasant army led by Augusto C. Sandino. Charles Evans

Hughes headed the U.S. delegation to the conference. Resentment increased in

Latin America against the U.S. intervention in the region, and Washington was

expecting a great deal of criticism. Two important issues debated at Havana

were the question of intervention and codification of public international law.

Unfortunately, the only decision that was reached was to defer the final

decision until the Seventh Conference. One of the projects relating to the

codification of public international law, entitled: "States:

Existence-Equality-Recognition," contained a provision that "no state

may intervene in the internal affairs of another.“64

As head of the

delegation Charles Evans Hughes in his address of February 18 declared:

"From time to time there arises a situation most deplorable and

regrettable in which sovereignty is not at work, in which for a time in certain

areas there is no government at all. What are we to do when government breaks

down and American citizens are in danger of their lives? Are we to stand by and

see them killed because a government in circumstances which it cannot control

and for which it may not be responsible can no longer afford reasonable

protection? Now it is the principle of international law that in such a case a

government is fully justified in taking action - I would call it interposition

of a tempo~ character for the purpose of protecting the lives and property of

its nationals."65 Put in such a context intervention was perceived as a

noble act; however Latin American countries could not accept it as their

reality and wanted to see a change in policy. The roots of transformation in

U.S. policy toward Latin America known as the Good Neighbor Policy are

associated with the administrations of Presidents Woodrow Wilson, Calvin

Coolidge and Herbert Hoover. The phrase "good neighbor" was used by

President Hoover during a ten-country tour of Latin America between his

election in 1928 and his inauguration in 1929. The new direction that Hoover

seemed to be promising was officially launched and implemented by President

Franklin D. Roosevelt, who served in the White House from 1933 until 1945. As

early as 1928, Franklin Roosevelt had publicly criticized the Coolidge and

Harding administrations for their failure to do more to create good will in

Latin America. He denounced the habit of intervention, though as assistant

secretary of the Navy in the Wilson administration, Roosevelt had played a key

role in the U.S. occupations of Haiti, the Dominican Republic and the Mexican

port of Veracruz. The United States attempted to reinterpret the Monroe

Doctrine and in the spring of 1930, the State Department published a memorandum

written by J. Reuben Clark when Under-Secretary of State, which rejected the

Theodore Roosevelt corollary of the Doctrine under which the United States had

claimed the right to police the Caribbean.66 But the Memorandum officially

endorsed by the Hoover administration declared that intervention might still be

justified by the necessities of self defense. Both

Mexico and Argentina when joining the League of Nations in 1931 and 1933, made

reservations declining to recognize the Monroe Doctrine under Article XXI of

the Covenant. In his inaugural address on March 4, 1933, Franklin Roosevelt

declared that his world policy would be that of ''the good neighbor - the

neighbor who resolutely respects himself and, because he does so, respects the

rights of others - the neighbor who respects his obligations and respects the

sanctity of his agreements in an with a world of neighbors." He used the

term "good neighbor" specifically in connection with LatinAmerica in this speech before the Governing Board of

the Pan American Union in Washington, on April 12, 1933, which was the

"Pan-American Day.“67 President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Good Neighbor

Policy encountered its first serious test in Cuba, where open warfare had

erupted against the dictatorial government of Gerardo Machado. Opponents of

Machado seemed to be leading the country toward a social revolution. In May

1933, Roosevelt appointed his assistant Secretary of State, Sumner Welles, as

the U.S. Ambassador to Cuba, with orders to resolve the crisis through mediation.

Machado resisted Welles's persistent efforts to convince him to resign until

the Cuban army turned against him in August and forced Machado to leave. Welles

efforts were frustrated, however, by his inability to control subsequent

events. In September, Welles choice for president, Carlos Manuel de Cespedes,

was overthrown and university professor, Ramon Grau San Martin, took power with

the support of a group of army sergeants, corporals and enlisted men led by

Sergeant Fulgencio Batista. Refusing to recognize Grau San Martin's

reform-oriented government, the United States continued to seek an alternative,

which it finally achieved in January 1934 when Colonel Fulgencio Batista,

switched his support from Grau San Martin to Carlos Mendieta.77 In this case

non-recognition of the government was used as a coercive tool to prevent Grau

San Marin from coming to power. As the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations

moved closer toward pledging Washington to a policy of nonintervention, Latin

Americans insisted that Washington make it official. To them, a legally binding

promise renouncing the right to intervene under any circumstance was the most

effective way for the United States to prove its commitment to nonintervention.

Such a promise had been asked of Washington at Havana in 1928 and denied. It

wasn't until Montevideo that the wish of the Latin American countries was

granted by the government in Washington.

Montevideo Conference

There was little

enthusiasm evident in the events preceding the Montevideo Conference. A number

of the influential foreign offices in South America cabled expressing their

doubts about the chances of the success of the conference. This was largely

based on the outcomes of previous conferences. Even though some ended in

agreements, the actions of states indicated they were not prepared to give up

their current practices. Skepticism was also stemming from the temporary

failures of the London Economic Conference and the Geneva Disarmament

Conference. According to Secretary Hull: "the statesmanship and leadership

and public opinion in many other parts of the world had become stagnant, and

passive, with the result that hopes of the friends and peace and progress and

the supporters of general economic rehabilitation were extremely

low".78 At the time there were even comments regarding possible

postponement of the conference until the conditions in Latin America became

more stable and open to cooperation.326 Parallel to this air of skepticism,

there was a movement to advance international law through codification. The

first Conference for the Codification of International Law was held at The

Hague from March 13 to April 13, 1930. The outcome of the conference were a

Draft Convention on Nationality, a Protocol on Military Obligations, and two

Protocols on Statelessness, submitted to the further consideration of the

govemments.79 In the preamble of the resolution of the Assembly of the League

of Nations which was adopted October 3, 1930, the following outline of policy

for codification is stated: "That the Assembly decides to continue the

work of codification with the object of drawing up conventions which shall

place the relations of States on a legal and secure basis without jeopardizing

the customary international law which should result progressively from the

practice of States and the development of jurisprudence.“80

Professor A. Pearce

Higgins, of Cambridge University, commented upon The Hague Codification

Conference as follows: "The word "codification" has several

meanings, and in the sense in which it is understood at The Hague, it meant

more than the compilation of a systematic statement of the existing law on the

several subjects, which is its ordinary significance. It meant the making of

new rules of law, in other words, legislation.81 Against all odds, the Seventh

International Conference of American States held at Montevideo December 3-26,

1933, proved to be one of the most successful and promising in accomplishment

of all of the Pan-American conferences.33o It marked the departure from

previous American conference as it allowed the observers from non American states (Spain and Portugal) and from a

non-American organization (the League of Nations) to be admitted.82 Moreover,

by 1933 the U.S. marines were finally out of Nicaragua, and President

Roosevelt's policy of non-intervention in Cuba opened the door for a new Pan

American policy. The Conference showed a movement of states toward greater

cooperation with European agencies for promoting better international

relations, and removing many sources of suspicion, fear and initation

between the United States and Latin American.83 In addition the proposal was

made that all nations give their adherence to the existing peace convention

since the Gondra Pact that have not been signed.84

This was an effort to show commitment to peace and non-intervention into the

affairs of other states. The agenda of the conference was quite lengthy

consisting of eight chapters and comprising twenty-eight major topics covering

social, political, economic, scientific, and literary issues. They included

both broad concerns such as the organizations of peace and problems of

international law as well as economic and financial problems to specific issues

of political and civil rights of women and transportation.334 Amazingly, there

were a total of ninety-five resolutions adopted by the conference. From the

beginning the Conference focused on two most important concerns: 1) to give Pan

Americanism an economic content, through emphasis that the American Republics

must remove the barriers to trade and reduce tariffs, abolish quota systems,

and other restriction of similar nature; and 2) to establish on a firm

foundations the doctrine of the equality of States, with a declaration against

the intervention of one State in the internal affairs of another.85 It was

precisely around these two questions the most important discussions and

decisions were centered. The conference addressed destructive commercial

policies, demanding that rising trade barriers be lowered to moderate level and

it developed a comprehensive program for economic rehabilitation, which

combined a policy of mutually profitable international trade with domestic

economic policies and programs.86

At Montevideo, there

were six conventions that were signed dealing with such diverse subjects as

nationality, extradition, political asylum, teaching of history and rights and

duties of states.87 Of great interest to the Conference was the Conference's adoption

of a report on the "Rights and Duties of States". This topic was

resolved in Montevideo. This document proposed four criteria of statehood. It

stated in Article 1:"The state as a person of international law should

possess the following qualifications: a) a permanent population; b) a defined

territory c) government; and d) capacity to enter into relations with the other

states.“88 Statehood, according to this definition, is not a factual situation,

but a legally defined claim to right, specifically to the competence to govern

a certain territory. In addition to statehood the Montevideo convention

embraced such matters as recognition, equality, non-intervention, and

territorial inviolability. Article VIII stated: "No state has the right to

intervene in the internal or external affairs of another."89 The

sovereignty of states was also re-affirmed in another declaration which stated:

"The territory of the States is inviolate and may not be the object of

military occupations or of other measures of force imposed by other States,

either directly or indirectly, or for any motive, or even of a temporary

nature.“90

Willingness of the

United States to abide by this principle was evident in the speech made by

President Roosevelt shortly after the close of the conference. Speaking before

the Woodrow Wilson Foundation on December 28, 1983 he asserted: "The

definite policy of the United States from now on is one opposed to armed

intervention.“91 Secretary of State Hull still insisted on adding a

"reservation“92 that left the door open to intervention under certain

circumstances, that were "generally recognized and accepted" by the

law of nations.93 With respect to the recognition of states, Article 3 of the

Convention stated: "The political existence of the state is independent of

recognition by the other states. Even before recognition the state has the

right to defend its integrity and independence, to provide for its conservation

and prosperity, and consequently to organize itself as it sees fit, to

legislate upon its interests, administer its services, and to define the

jurisdiction and competence of its courts. The exercise of these rights has no

limitation than the exercise of the rights of other states according to

internationallaw."94

Article 6 of the

Convention pointed out: "the recognition of a state merely signifies that

the state which recognizes it accepts the personality of the other with all the

rights and duties determined by international law. Recognition is unconditional

and irrevocable.“95 The Conference recognized that the existing peace

instruments would be sufficient to guarantee peace, the progress of law and

international justice and the abolition of the use of force and violence only

if they were ratified by states. Therefore, under Chapter I of the Conference

titled "Organization of Peace" a resolution was passed for all member

states to ratify the peace treaties. These instruments included: the Treaty for

Avoiding and Preventing Conflicts (Gondra Treaty)

signed at Santiago, Chile in 1923; Kellogg-Briand General Pact for the

Renunciation of War, signed at Paris, in 1928; General convention of

Inter-American Conciliation, signed at Washington, in 1929; General Treaty of

Inter-American Arbitration, signed at Washington in 1929; Anti-War Pact,

initiated by Argentina and signed at Rio de Janeiro, in 1933.96 The Conference

adopted a resolution inviting the countries represented to adhere to those

instruments. The significance of the ratification of peace instruments was also

pointed out by Secretary Hull in an address before the National Press Club,

February 10, 1934, shortly after his return from Montevideo: "The peace

agencies of this hemisphere, five in number, hitherto inefficient because

unsigned by some 15 governments, with the result that two wars had been

permitted, were promptly strengthened by the signatures or pledges to sign of

the 15 delinquent governments. Our peace machinery as thus strengthened will,

according to all human calculations, prevent future wars in this hemisphere.“97

Even though it was

not initially on the agenda, the Conference also dedicated itself to finding a

peaceful means to ending the war between Bolivia and Paraguay over the Chaco

region. On August 3, 1932 nineteen American states declared that no territorial

arrangement should be recognized which had not been obtained by peaceful means.

98 The anti-war pact, initiated that same year by Argentina and signed on

October 10, 1933 at Rio de Janeiro by six American states, reiterated this

declaration. For example, previously all of the efforts including a Commission

of Neutrals presided over by the United States, or the ABC-Peru group

(Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Peru), and the League Council had failed to

establish peace in the Chaco. On July 3, 1933, the League Council decided to

send a commission to the Chaco to negotiate agreements for arbitration and

cessation of hostilities and to conduct a full inquiry into the dispute. The

League commission then went to Montevideo in hope that the Conference would

offer some solutions for the dispute. The issue was of such relevance that the

President of Uruguay, Dr. Gabriel Terra used his opening remarks to urge all

states present to work hard in finding peaceful solutions through arbitration

to the conflict. 99

At the first meeting,

of the Committee on the Organization of Peace, a subcommittee on the Chaco was

appointed, composed of the chairmen of the delegations of Argentina, Brazil,

Chile, Peru, Mexico, Guatemala, and Uruguay. The purpose of this effort was to

study the possibilities and the way in which the conference could cooperate

with the Committee of the League of Nations that was inquiring into the

situation of the Chaco. One week before the end of the conference, a ceasefire

was announced which was extended until January In addition to the Convention on

the Rights and Duties of States the conference at Montevideo approved three

other conventions on international law: on nationality, on extradition, and on

political asylum. It furthermore approved a program for continuing in the

future the work of codifying international law. In article LXX on the Methods

of Codification of International Law the conference stated: "That the

codification of international law must be gradual and progressive, it being a

vain illusion to think for a long time of the possibility of carrying it out

completely."100

Pointing out that

Conference acknowledged the necessity of adopting new methods and procedures

for the organization of the work of Codification of Public International Law

and of Private International Law in America, the Conference stressed that it is

necessary to do practica work and to seek the

conjunction of the juridical viewpoints.101 With reference to this point, a

resolution was passed providing for: "1) the maintenance of the

International Commission of Jurisconsults created by the Rio Conference of 1906

and to be composed of jurists named by each Government; 2) the creation by each

Government of a national committee on codification of international law; 3) the

creation of a commission of experts of seven jurists with the duty of

organizing and preparing the work of codification.“102 While the Sixth

Conference of Havana condemned wars of aggression, the Montevideo Conference

extended that condemnation to all wars.103 President of Uruguay Gabriel Terra,

in his address of the Conference pointed out that there is a parallel between

the programme of work of the Conference and the

general programme upon which the League of Nations

has been working on the basis of universality. He found the similarity

"inevitable as inter-state relations turn upon questions of pacific

settlement, economic and commercial relations, improvement of legal and judicial

procedure, and progress through greater uniformity in social and humanitarian

legislation."104

President Terra

stated: "Let us repeat with President Roosevelt, the utterance of his

illustrious predecessor, McKinley, in his public message of 1909: The period of

exclusion has ended. The period of cooperation and expansion of trade and

commerce is the problem of the moment. The treaties of reciprocity are in

harmony with the spirit of the times, but not so the measures of

retaliation.“105 Consensus on territoriality and effectiveness by the eve of

Montevideo probably explains the lack of analysis regarding the elements of the

Convention. However, consensus obscured that these concepts were not absolute.

Though the Montevideo criteria were very much a part of the international legal

environment by 1933, territorial power and effectiveness had not monopolized

state theory for very long. Well into the nineteenth century, statehood was

thought to be bound to a set of political criteria as much or more than the

fact of territorial power. Legitimism was at times the prevailing concept in

theory and practice concerning statehood. The interesting question regarding

the conference is why Pan-American powers in 1933 decided to announce what

constitutes a state? At that time in history both notions of effectiveness and

territoriality were prevalent in international affairs. In addition several

Latin American states had displayed the inclination before the conference to

codify international norms as was evident in Estrada and Tobar Doctrines.

Inclination for codification reflected the Roman law roots of Latin America legal

system. The American Law Institute (ALI) was established in 1923 to promote the

"clarification and simplification of the law and its better adaptation to

social needs." The United States at the time was in the Restatement

movement. The Restatements, the ALl's principal work

product, were formulated by committees of judges, scholars, and practitioners

selected for their reputation in different fields of law.105

It is possible that

the same quasi legislative, quasi-academic inspiration to organize the common

law into code-like compilations which had moved the ALl

had also moved United States State Department lawyers. Internationalism

prevalent in much of the interwar world made for an environment conducive to

the Montevideo agenda.106 One point that is of crucial importance and at the

time was a surprise to other countries was the Reservations that the delegation

of the United States made in signing the Convention on the Rights and Duties of

States. While the delegation did recognize the importance of non-intervention

and it committed to upholding this principle, it felt uneasy about committing

to the eleven articles of this convention dealing with the most fundamental

questions. The reservation stated the following: "I think it unfortunate

that during the brief period of this Conference there is apparently not time

within which to prepare interpretations and definitions of these fundamental

terms that are embraced in this report. Such definitions and interpretations

would enable every government to proceed in a uniform way without any

difference of opinion or of interpretations.“107

This statement and

reservation clearly shows the uneasiness on the part of the United States to

accept the definitions of statehood and recognition. It further points to the

fact that Montevideo was never truly about those matters but rather about

non-intervention. The numerous failed attempts to codify statehood in the

period after Montevideo clearly show the ambiguity of the terms and

unwillingness and uneasiness of the countries to commit to a blue print on such

fundamental terms. Post-Montevideo attempts toward codification Montevideo

Conference provided only the basic criterion for statehood. Even though the

criteria are rather vague and insufficient requirement for statehood, to this

day it remains the single most referred to document with respect to questions

of statehood. In addition, it remains the only time in history that countries

were willing, able and the conditions in the world enabled them to codify

statehood. The Montevideo definition is often quoted on the subject of

recognition of States. The Institute of International Law in 1936 defined

recognition as "the free act by which one or more States acknowledge the

existence on a definite territory of a human society politically organized,

independent of any other existing State, and capable of observing the

obligations of intemational law, and by which they

manifest therefore their intention to consider it a member of international

community.“108 The definition of recognition became a replica of the Montevideo

Convention. The two concepts from that point were often blurred together which

caused for a lot of confusion and ineffectiveness. Following Montevideo, the

issue of recognition was again addressed at the meeting of the International

Law Commission between 12 April and 9 June 1949. At that meeting, it was

pointed out that the question of recognition was mentioned in paragraph 42 of

the Secretary-General's memorandum and noted that the transition from

individual action of states to collective recognition would mark a step forward

in the development of international law . It was further stated that the

question had often been considered a political rather than a legal question.108

Furthermore, the chairmen of the meeting reiterated that the question of

recognition was not resolved at The Ninth International Conference of American

States.110 The debate referred back to the Draft Declaration on the Rights and

Duties of States and questioned whether there should be universally accepted

criteria as a guide for deciding which bodies of people could be recognized as

states.111

The International Law

Commission concluded that the question of recognition was too delicate and too

fraught with political implications to be dealt with in a brief paragraph in

the Draft Declaration on Rights and Duties of States, and it noted that the topic

was one of fourteen topics the codification of which has been deemed by the

Commission to be necessary or desirable.113 The topic of recognition of states

and governments has been debated by the International Law Commission from 1949

to 1973. At the 1973 session, during a discussion on the future work programme, the consensus was that: "The question of

recognition of states and governments should be set aside for the time being,

for although it had legal consequences, it raised many political problems which

did not lend themselves to regulation by law.“112

There have also been

numerous unsuccessful efforts to codify statehood. General Assembly Resolution

3314 of 14 December 1974 adopted a definition of aggression, explained in

Article 1 that the term State is used without prejudice to questions of

recognition. In the same year, the International Law Commission selected

fourteen topics for codification, one of which was the recognition of States

and governments.113 One member of the Commission concluded "the question

of recognition of States and governments should be set aside for the time

being, for although it had legal consequences, it raised many political

problems which did not led themselves to regulations

by law.“114 The subject was never codified. Although a definition of the word

'State' was not set forth in a separate legal instrument, the International Law

Commission did concern itself with suggested definitions in the framework of

general declarations or conventions. The first attempt to clarify the meaning

of the term 'State' was made in 1949 with regard to a draft Declaration on the

Rights and Duties of States. Special Rapporteur Alfaro had not included an

article on statehood in his draft, as he thought that ''the definition of the

State had no place in a Declaration on the Rights and Duties of States.“115

He stated that

"if a country did not satisfy the conditions required for the existence of

a State, it was not a State; on the other hand, if a State existed, that meant

that it had fulfilled the conditions necessary for its existence and that it

could not be called upon to fulfill those conditions.“116 India and the United

Kingdom had urged the inclusion of a definition of the term 'State', but the

International Law Commission did not think it would come to a consensus on its

meaning.118 The International Law Commission decided not to include a

definition of 'State' in the draft Declaration and stated that the word had

been used without definition before and that there was no useful purpose that

would be served by defining the term.119 It was decided that the word 'State'

would be used "in the sense commonly accepted in international

practice".120 Hence, the term was left undefined and ambiguous. The same

discussion arose at the time of the drafting of the Convention on the Law of

Treaties. In the Article 'use of terms' of the draft Convention, Special

Rapporteur Firzmaurice envisaged the definition of

the term 'State'. His draft Article 3 of 1956 which stated: "a) In

addition to the case of entities recognized as being States on special grounds,

the term "State": (i) means an entity

consisting of a people inhabiting a defined territory, under an organized

system of government, and having the capacity to enter into international

relations binding the entity as such, either directly or through some other

State; (ii) Includes the government of the State,121

In essence, this

reflected the declaratory theory. He added that recognition was only

constitutive when an entity does not otherwise qualify as a State i.e. the

States on special grounds. A later draft Article of 1966 aimed at adding to the

present Article 6 of the Vienna Convention: "The term "State" is

used in this paragraph with the same meaning as in: (a) the Charter of the

United Nations; (b) the Statute of the Court; (c) the Geneva Conventions on the

Law of the Sea; (d) the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, i.e. it

means a State for the purposes of International Law.“122 Neither draft

proposition was ever adopted. After all the above debates and attempts to

codify statehood, the definition of a State remains acontroversial

and politically loaded subject. Even though the contribution of Montevideo to

statehood and our understanding of the concept is limited, the success of the

conference with respect to making intervention illegal and setting standards

for both economic and political cooperation was significant. Montevideo was the

beginning of development of good relations between the United States and Latin

America. The Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance between the United

States of America and other American Republics, also known as the Rio Pace75 of

1947 was in essence an extension of Montevideo. It represented a significant

development in international security. From codifying statehood, establishing

equality of all states and committing to non-intervention at Montevideo, the system

evolved to countries' condemning war and aggression, committing to collective self defense and resolving disputes by peaceful means at

Rio. Interestingly while during Montevideo the Untied

States was viewed as an aggressor, Rio Treaty under Article 3 points out that

"an armed attack by any State against an American State shall be

considered as an attack against all the American States and, consequently, each

one of the said Contracting Parties undertakes to assist in meeting the attack

in the exercise of the inherent right of individual or collective

self-defense“123 Therefore aggression or the threat of aggression would

necessitate consultation among the American Republics with a possibility of

collective measures of defense. This was a giant step in the right direction

with respect to achieving a sound security mechanism for the whole region.

1 Pasquale Fiore,

International Law Codified and its Legal Sanction or the Legal Organization of

the Society of States. p. 36.

2 Even though the

agenda ofthe conference was available at the New York

Public Library, there were no minutes of the meetings nor was there any

evidence in writing of the proceedings and discu5sions that took place with

respect to the criteria of statehood.

3 Willhelm G. Grewe,

The Epochs a/International Law, p. 497.

4 Ibid.

5 J.A. Frowein "Die Entwicklung der Anerkennung yon Staaten and Regierunged im Voelkerreicht" (1972 11 Der Staat 158) in Grewe The Epochs of International Law,

p.498.

6 Harold Temperley,

The Foreign Policy of Canning 1979-/939, pp.498-500 266 Willhelm G. Grewe, The

Epochs of International Law, p. 499

7 Willhelm G. Grewe,

The Epochs of International Law, p. 499

8 Raymond Leslie

Buell, The Montevideo Conference and the Latin American Policy of the United

States, Foreign Policy Reports, Vol. IX, No. 19, p. 213.

9 Ibid.

10 James Brown Scott,

International Conferences of American States, p. 3.

11 Ibid. pp. 40-43.

The treaty based on this plan was signed by eleven states (Bolivia, Brazil,

Ecuador, Guatemala, Haiti,Honduras, Nicaragua, EI

Salvador, United States, Uruguay and Venezuela - but lapsed through the failure

of all its signatories to exchange ratifications within the required time.

12 Raymon Leslie

Buell, The Montevideo Conference, p. 214.

13 The Hague Peace

Conference of 1899 marked the beginning of a third phase in the modem history

of international arbitration. The chief object of the Conference, in which - a

remarkable innovation - the smaller States of Europe, some Asian states and Mexico

also participated, was to discuss peace and disarmament. It ended by adopting a

Convention on the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes, which dealt not

only with arbitration but also with other methods of pacific settlement, such

as good offices and mediation. With respect to arbitration, the 1899 Convention

made provision for the creation of permanent machinery which would enable

arbitral tribunals to be set up as desired and would facilitate their work.

This institution, known as the Permanent Court of Arbitration, consisted in

essence of a panel of jurists designated by each country acceding to the

Convention.

14 The Treaty of

Compulsory Arbitration was ratified by the Dominican Republic, Guatemala,

Mexico, Peru, El Salvador, and Uruguay, and the Treaty of Arbitration for

Pecuniary Claims was ratified by Columbia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala,

Honduras, Mexico, Peru, El Salvador, and the United States and was extended at

the third conference. See Scott, pp. 100-105. 132-133.

15 Carlos Davila, The

Montevideo Conference: Antecedents and Accomplishments, International

Conciliation Documents for the Year 1934, p. 123.

16 Antonio S. de

Bustamante, America and International Law, p. 164.

17 This convention is

in force as regards the United States, Bolivia, Brazil, Costa Rica, Dominican

Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, and

Uruguay, Department of State, Treaty Information, December 31, 1932.

18 Raymond Leslie

Buell, The Montevideo Conference, p. 215

19 The First Hague

Convention bad proposed the creation of international commissions of inquiry to

be fact -finding and without arbitral award. Other attempts include the Treaty

on Compulsory Arbitration adopted at the Second International Conference of American

States as well as the Bryan treaties of 1913 and 1914.

20 The Santiago or Gondra Treaty of 1923 was ratified by nineteen of the

twenty-one republics: United States, Brazil, Chile, Columbia, Costa Rica, Cuba,

Dominican Republic. Ecuador, Guatemala,

Haiti. Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, EI Salvador,

Uruguay, Venezuela. The two countries

that did not sign were Argentina and Bolivia. Department of State. Treaty Infonnation, December 31, 1932 and Diorio of the Montevideo

Conference. No. 14, p. 6.

21 Carlos Davila, The

Montevideo Conference: Antecedents and Accomplishments, p. 124.

22 Carlos Davila, The

Montevideo Conference: Antecedents and Accomplishments, p. 124.

23 The International Conunission of Jurists was set up by the Third Conference

in 1906.

24 Antonio D. De

Bustamante, American and International Law, The Pan American Union Bulletin 3,

p. 158.

25 Ibid. p. 159

26 Ibid.

27 This is the same

time that the Kellogg-Briand Pact was signed - August 27, 1928. This agreement

similarly to the Washington Conference condemned "recourse to war for the

solution of international controversies. In June 1927 Artistide

Briand Foreign Minister of France proposed to the US government a treaty

outlawing war between the two countries. Frank B. Kellogg, the US Secretary of

State returned a proposal for a general pact against war and after prolonged

negotiations the Pact of Paris was signed by 15 nations: Australia, Belgium,

Canada, Czechoslovakia, France, Germany Great Britain, India, the Irish Free

State, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Poland, South Amca and the US. The

contracting parties agreed that all settlements of conflict that might arise among

them should be sought only by pacific means and that war was to be renounced as

an instrument of national policy. Although 62 nations ultimately ratified the

pact, its effectiveness was undermined by its failure to provide measures of

enforcement.

28 Resolution adopted

February 18, 1928 Final Act, p. 175

29 Convention: Brazil,

Chile, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, EI Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti,

Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, United States, Uruguay.

30 General Treaty:

Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, EI Salvador, Guatemala,

Haiti, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, United States, Uruguay.

31 "Apparently because

it believed this reservation nullified the obligatory arbitration provisions of

the agreement, the State Department has not proceeded to ratify the arbitration

treaty." Raymond Leslie Buell in The Montevideo Conference on the Latin

American Policy of the United States (Foreign Policy Reports, Vol. IX, No. 19

November 22, 1922).

32 Carlos Davila,

Montevideo Conference, p. 126.

33 L. Thomas Galloway

Recognizing Foreign Governments. The Practice of the United States (1978) 27.

34 Cited in Brown,

Legal Effects of Recognition' 44 American Journal of International Law, p. 62.

35 Ibid.

36 Mexican Secretary

of Foreign Relations Don Genaro Estrada established that recognition and

nonrecognition policy of governments is not proper policy and the state

contemplating a change in the internal organization of another should simply

respond to the de facto situation.

37 The text of

Estrada is cited in 25 American Journal of International Law, supp. 203 (1930).

38 Ibid.

39 In President

Wilson's policy statement on this subject he declared ''that just government

rests always upon the consent of the governed, and that there can be no freedom

without order based upon law and upon the public conscience and approval":

See Hackworth Digest of International Law. vol. 1 (1940) 181.

40 Address by the

Honorable Henry L. Stimson before the Council on Foreign Relations, New York

City, February 6, 1931. The United States and the Other American Republics,

Publication of the Department of State, Latin American Series, No.4, p. 1.

41 Ibid., pp. 2-3.

42 Ibid., p.6

43 Address by

Honorable Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of State, p. 8

44 Address by

Honorable Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of State, p.9

45 Address by the

Honorable Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of State before the Council on Foreign

Relations, New York City, February 6, 1931, Publications of the Department of

State, Latin American Series, No.4. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington

1931.

46 Carlos Calvo, Le

droit international theorique et pratique (5th ed., Paris, 1896) 1:350-51, 231,

140, 142,

47 Quoted in Donald

R. Shea. The Calvo Clause: A Problem in Inter-American and International Law

and Diplomacypp. 17-19.

48 Ibid.

49 See Mexican

Constitution art 27 (I) Calvo's principles attracted international support in

the 1970s appearing in a variety of international resolutions, including the

U.N. General Assembly Resolution of 1973 - declaring the New International

Economic Order - and the 1974 U.N. Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of

States Art.2 of the Charter declares the laws governing nationalization and

expropriation of property are those of the nationalizing state and not those of

international law.

50 Robert H. Holden

and Eric Zolov, Latin America and the United States:

A Documentary History, No. 23.

51 The Monroe

Doctrine was proclaimed by President Monroe on December 9, 1823 in President

Monroe's address to Congress. This proclamation of essential principle of

American foreign policy in the Western Hemisphere was induced by several

factors - the intervention of the three absolute monarchies of Russia, Austria,

and Prussia ("Holly Alliance") in the affairs of other European

countries, the fear that they might attempt to overthrow the newly independent

Latin-American states and restore them as Spanish colonies, and Russian claims

in the Western Hemisphere. Alvarez, The Monroe Doctrine, 6-7 (1924).

52 Raymod Leslie

Buell, The Montevideo Conference, p. 217.

56 U.S. Department of

State. "Message" Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the

United States, 1898 pp. 750-60 Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1901.

57 Abram Chayes, The

Cuban Missile Crisis: International Crisis and the Role of International Law,

p. 122

58 Clark, Memorandum

on the Monroe Doctrine, December 17, 1928, State Department Publication, XXIII

, 1930

59 Treaties,

Conventions, International Acts, Protocols and Agreements between the United

States of America and Other Powers, 1776-1909, compiled by William M. Malloy

(Washington, D.C. 1910), Vol. II. p. 2025.

60 Ibid.

61 John Morton Blum,

The Republican Roosevelt, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1967 p.

127.

62 James Brown Scott,

The Seventh International Conference of American States, AJIL, p. 225.

63 John Morton Blum, The

Republican Roosevelt, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1967 E.127.