Nicolau Eymeric (ca. 1320-1399)

reported in his Directory of Inquisitors (Directorium

inquisitorum) that he had confiscated and burned the

“The Key of Solomon” (Clavis Salomonis).

Also ‘Necromancy’ was

not so broad a term as to cover all varieties of magic that were suspected by

authorities of involving demonic power. Rather, it was a decidedly learned art

involving complex rituals and ceremonies, often patterned on the church's own

liturgical rites, and knowledge of this art was typically conceived as being

contained in books or manuals. For example in the early fifteenth century,

religious reformer Johannes Nider (ca. 1380-1438)

reported that he knew a certain monk in Vienna who, before entering the

religious life, had been a necromancer and had possessed several demonic books.

Some of these texts survived inquisitorial flames and now allow remarkably direct

access into one area of the world of medieval magic. And one example

a fifteenth-century necromantic manual, titled Sworn Book of

Honorius the Magician (Liber iuratus Honorii) contains following illustration:

Since necromancy was

essentially a bookish art, its practitioners necessarily belonged to the small,

educated elite who possessed the Latin literacy necessary to use such manuals.

This meant that necromancers were virtually always clerics. The ranks of the

clergy in the Middle Ages extended down from priests through a variety of more

minor orders, and it was these lower orders that most likely supplied the

majority of necromancers. Medieval schools and universities were religious

organizations, so most students were formally required to become clergy. Thus

virtually all educated people were by definition clerics. After receiving their

degrees, however, these men might have few or no official ecclesiastical

functions.

Much Muslim and

Jewish magical literature furthermore discussed invoking and controlling demons

or spirits in the name of God. Demons could either alter their own forms or

they could affect human perception so that people thought they saw a horse, a

boat, a banquet, or anything else the magician might desire. Aside from

deceiving the senses, demons could also affect the human heart and mind, and so

necromancy could be used to arouse love or hatred, to bring calm or incite

agitation, and so forth. Just as in divination, here too there were debates

about the extent to which human will might be directly affected by magical

practices. (See Richard Kieckhefer, Magic in the Middle Ages, Cambridge

University Press, 1989).

Many authorities

reasoned that demons only had power over human bodies, but that by affecting

the body in certain ways (manipulating bodily humors, for example), they could

induce various mental states, or at least cause people to succumb to such

states more readily. Demonic power over bodies of course allowed them to

inflict physical harm on people and to cause disease. They could also heal,

however, and so through them necromancers also commanded all these powers. And

the belief that interaction with demonic forces was inherently evil and

corrupting had been an essential aspect of church doctrine since the earliest

days of Christianity. From the time of Augustine, Christian authorities had

condemned magic primarily because of the potential involvement of demons in the

rituals and practices that they deemed to be magical. They could hardly now

fail to condemn ritual that was explicitly demonic in nature. That some

necromancers claimed, by virtue of their position as clerics and more basically

by the power of Christ, that they could interact safely with demons and command

them toward positive ends was hardly an effective defense; in fact it

constituted a significant challenge to the longstanding position of the church.

Augustine had noted that most magic was based on evil associations between

humans and demons, and Aquinas had argued that even when a magical ritual did

not com in any explicit submission to demons,

nevertheless a tacit pact might be supposed to exist between the magician and

the entities he summoned. Necromancy, a type of magic contained in Latin

manuals and performed by clerics, was probably the form of magic most familiar

to Christian authorities in the high and late Middle Ages. As concern on the

part of authorities over magic grew in this period and condemnations of magical

practices increased, they were shaped largely by conceptions of elite

necromancy, but applied ultimately to all varieties of magic and superstition.

(See Richard Kieckhefer, Forbidden Rites: A Necromancer-'s Manual, 1998).

By the late

Middle Ages, authorities came to regard magic more seriously, and as a more

serious threat, so that this era was also marked by the increasingly rigorous

and intellectually specific condemnation of many forms of magical practice, as

systematic demonology and awareness of explicitly demonic necromancy fed

longstanding Christian concerns about the potentially demonic nature of all

magic and the demonic threat behind superstition. Legal advances also took

place in this period, above all the use of inquisitorial methods in court

proceedings. These methods allowed more readily for prosecutions and

convictions in cases involving charges of magical practices. In addition,

specially designated inquisitors began to appear who (eventually) brought cases

of heretical demonic magic under their jurisdiction. To support these new

procedures and personnel, advanced legal literature and theory developed, which

defined the illicit qualities of magic more precisely than ever before. Legal

condemnations of magic thus became as profound and encompassing as earlier

moral condemnations had been.

Already in the

Symposium, Plato's Socrates claimed that the gods never have direct contact

with humans. Instead, they employ the daemons, beings halfway between gods and

humans, as their intermediaries or messengers. Plato's term daimonion gave the

West its word for demons, his word for messenger, angelos,

the word for angels. When God begins to seem impossibly distant, Western

Christians rediscover angels and demons. If these messengers begin to seem

distant or unreal as well, someone begins daydreaming that somewhere-somewhere

close – other people must be experiencing superhuman reality, physically,

empirically, unmistakably. The thirteenth century was a crucial period in the

development of necromancy as both idea and practice. This was the age of

Aquinas, and there is clear evidence that necromancy was already under

consideration as a way of investigating whether spirits really existed or were

capable of interaction with humans. Around the time Aquinas was born, the

German Cistercian monk Caesanius of Heisterbach wrote his Dialogus miraculorum, or Dialogue on Miracles (1225), which was very

influential in the later Middle Ages. Coming to terms with the

imperceptibility, improvability, and possible nonexistence of the spirit world

happened gradually, in step with a reluctant acceptance of the extraordinary

power of the human imagination.

In Religion and the

Decline of Magic, Keith Thomas asserts that, in the early-modern period,

"the evidence of widespread religious skepticism is not to be underrated,

for it may be reasonably surmised that many thought what they dared not say

aloud." He suggests that "not enough justice has been done to the

volume of apathy, heterodoxy, and agnosticism which existed long before the

onslaught of industrialism. It is generally accepted however that the witch

hunts, magical activities becoming an official matter, was immensely influenced

by the centuries of constant, religious conflicts and threats-usually taking

the form of religious wars between Christians and Muslims or between Catholics

and Protestants.

How strange to see a

Franciscan philosopher-theologian arrive at a conclusion essential to scientific

thinking by asserting the freedom of an omnipotent God to do as he wishes.

Using hindsight, one can see Thomas Aquinas supplying the first part of a

scientific worldview by emphasizing the existence of knowable causal patterns

in an integrated, interdependent natural universe. Aquinas and other

representatives of the via antiqua assumed the

existence of metaphysical "entities" originally derived from

Aristotle, such as a "potential intellect" that permits humans to

receive and store information, and an "active intellect" that permits

them to analyze it. But while Christian theologians could not settle for the

observation that magic simply "worked," their Muslim counterparts

could and did. Muslims believe that by reciting the last several sentences of

the Qur'an following the five daily prayers, they neutralize all evil, forces.

Thus at least one, irony about the European witch-hunts might be that they were

the result of reason and logic applied to a false premise.

Clerical authorities

furthermore linked magic categorically to pagan rites and demonic powers, and

thus they condemned all magical activity as inherently immoral and illicit for

Christians. Of course, these distinctions were never clear-cut or absolute in

practice, as moral judgments were always deeply intertwined with legal rulings.

Even in the ancient world, legal condemnations could become quite general in

tone, and any type of illicit magical practice could be regarded as a threat to

the community's harmonious relationship with divine or spiritual forces. In

Christian Europe, kings and princes relied heavily on clerics and on the church

to buttress their authority. Thus the church's condemnation of magic had legal

effects, and law codes were always based on Christian morality. In the high and

late Middle Ages, however, the church itself became a much more legalistic

entity. Canon law, based on church rulings or "canons," developed

into a science at the new schools and universities that appeared in this

period, and increasingly the church came to define itself and its authority in

terms of these legal codes. Ecclesiastical courts developed to enforce this

law, which applied to all Christians. Ultimately, specialized officials

appeared-inquisitors whose purpose was to root out the worst offenders against

church law, those Christians who denied or rejected essential elements of their

faith or aspects of church authority and so became heretics. Because of their

perceived involvement with demons, people who engaged in many types of magical

practices were eventually included in this category.

The history of the

condemnation of magic in this period culminated in the emergence of the

essentially new category of diabolical, conspiratorial witchcraft. Although

people had been suspected, accused, and prosecuted for performing harmful or

malevolent sorcery-maleficium-throughout the

Christian era, as in antiquity, only in the fifteenth century did the idea

develop that people might engage in maleficium as

members of heretical, demon-worshiping cults, offering themselves to Satan in

exchange for power and acting at his direction to corrupt and subvert all of

Christian society.

Of course, because of

their rejection of Christianity, Jews were easily depicted as being in league

with demons. One legend related how the early sixth-century Christian saint

Theophilus had been tempted by a Jewish sorcerer into signing a pact with the

devil in order to gain magical powers. This story became an archetype for later

notions of diabolical pacts associated with magic and witchcraft. Thus

promising a copy of the notorious Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses, an

advertisement in the Allgemeiner Litterarischer

Anzeiger, 28 March 1797, drew considerable attention.

Of course this now was when the 'Magic Media Market' was being formed. A copy

from around 1750 (probably not long after the fake was created) is housed in

the British Library. It consists of twenty-two loose, bronze-coated cardboard

pages measuring 30.5 x 44.5 centimeters. They each have writing on the front

and the back, mostly in blood red characters that are or at least appear to be

oriental. The sections of text that are formulated in German, the headings in

particular, are also written using Latin letters, which are blended with the

oriental signs. During the late 1950’s a German Judge suddenly felt the need to

declare the Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses (by now part of folklore)-- as

“anti-Semitic.”( Hans Sebald, The 6th and 7th Books

of Moses: The Historical and Sociological Vagaries of a Grimoire', Ethnologica Europea 18, 1988,

53-8).

Furthermore an

inquisition, inquisitio in Latin, originally did not

imply an ominous institution, but simply meant a process of legal inquiry.

Bishops and their officials were expected, as a matter of course, to inquire

into any potential errors of faith within their jurisdictions. However by the

twelfth century, as heresy became a greater concern, inquisitorial procedures

became more intense and systematized. Seemingly distant from the process of

inquisition, confession was actually closely related, for it involved, or was

supposed to involve, a personal inquiry by an individual, although directed by

a priest, into his or her own beliefs and moral state, leading to

acknowledgment and repentance of any errors. This was also the underlying moral

goal of an inquisition, and authorities' growing preoccupation with uncovering

and uprooting potentially improper beliefs was a critical factor in the

developing condemnation of heresy, as well as the condemnation of magic and

superstition.

Thus growing

reliance on inquisitions marked the emergence of a new type of legal procedure

in Europe , where suspected sorcerers might be required to grasp hot irons, and

in several days their wounds would be examined to determine whether they were

healing properly (little or no healing was a sign of guilt), or suspects might

be bound and dunked in water to see how quickly they rose to the

surface--floating was a sign guilt. Plus if an entire community regarded

an individual with suspicion, punishment could occur, and it was often severe.

In 1075 for example, citizens of Cologne (now Germany) threw a woman from the

town wall because they believed she was practicing magical arts. In 1128 the

people of Ghent (now Belgium) eviscerated an "enchantress" and paraded

her stomach around the town.

The first evidence of

the legal use of torture comes from statutes of the Italian city of Verona in

1228, regarding the use of torture by secular courts. In 1252 Pope Innocent IV

(reigned 1245-1254) permitted papal inquisitors to use torture to extract

information from suspects. To obtain a conviction for a potentially capital

offence, standard legal procedure came to require either the testimony of two'

eyewitnesses or the confession of the accused. Given the clandestine nature of

most magical practices, eyewitnesses were usually out of the question~

Authorities certainly recognized the potential of torture to extract false

confessions, and they devised methods and imposed limitations intended to

reduce this risk. Nevertheless, especially in cases involving accusations of

demonic sorcery, authorities often set these restraints aside. The unrestrained

use of torture would become a hallmark of most of the major witch hunts of

subsequent centuries.

Inquisitorial concern

about ‘magic’ continued to develop over the course of the fourteenth century,

and theories regarding the essentially demonic nature of most forms of magic

became increasingly elaborate and definitive. And as the fourteenth century

progressed, condemnations of magic came from outside inquisitorial circles as

well. In 1398 two Augustinian monks were executed in Paris after they had

failed in their attempts to relieve the intermittent madness of the French king

Charles VI (reigned 1380-1422) and then accused his brother Louis of Orleans of

having used magic against him. Louis' wife was also accused of practicing

sorcery. After Louis' death in 1407, charges of magic again circulated against

him. Most importantly, in close connection to this web of concern at the royal

court, the theological faculty of the University of Paris, the preeminent

intellectual institution in medieval Europe , issued a broad condemnation of

sorcery, divination, and superstition in 1398. The twenty-eight articles of the

Paris condemnation tended to dwell mostly on the sort of elaborate, ritual

magic that clerical necromancers would perform.

The stereotype of

witchcraft that emerged in the course of the fifteenth century was not an

absolutely stable idea that once constructed, remained constant and

unchallenged in all its aspects. Most people accepted the potential reality of

harmful magic and feared its power, and basic notions of demonic threat hiding

behind common magical practices and superstitions were widely accepted,

certainly among authorities. Even when authorities disagreed about the extent

of demonic power in the world, they acknowledged· the existence of the devil

and his desire to corrupt Christian souls.

Called in French sorciere (derived from the late-Latin sortiarius,

or diviner and German Hexe, between 1626 and 1630, the central German city of

Bamberg executed around six hundred people for this crime of the mind, among

them the mayor of the city, Johannes Junius.

To be a witch was as

much about a person's essential identity as it was a description of certain

practices, for unlike other perceived practitioners of magic, witches were not

just individual agents of harm or ‘malevolence’ in the world. Instead, they

became members of a vast, diabolical army bent on corrupting and subverting

everything that was good and decent in society. Thus the first major theorists

of witchcraft, writing in the early fifteenth century, described groups of

witches gathering to worship demons, engage in orgiastic sex, desecrate

crosses, befoul consecrated hosts, and murder and devour babies at

cannibalistic feasts. For all the fantastic and monstrous acts authorities

envisioned taking place at sabbaths, however, they still could place them in

fairly mundane and realistic settings. Small groups of witches would gather in

cellars, caves, or other isolated but entirely worldly locations.

These beliefs appear

to have had tremendously deep cultural roots, into which authoritative

constructions of witchcraft inadvertently tapped. In many premodern societies,

individuals, whom scholars now typically refer to as shamans, confronted evil

spirits and sought to protect human communities, working to guarantee

fertility, abundant crops, and successful harvests. The superficial although

inverted similarity of such figures to witches, who were typically accused of

impeding fertility and destroying crops, is clear, and in the 1960’s, the

Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg discovered a remarkable historical convergence

of these beliefs.(For the English translation see Ginzburg, The Night Battles:

Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1983).

The presence of one

witch in a region therefore indicated the existence of more, and a captured

witch could reasonably be expected (and frequently forced) to identify others.

This notion that witches were not merely individual malefactors but members of

a satanic conspiracy bent on subverting Christian society led not only

religious but also secular authorities to treat witchcraft very harshly. The

threat posed by witchcraft was seen to be so great that authorities in many

jurisdictions declared it to be a crimen exceptum, an exceptional crime, This meant that normal

legal procedures could be suspended, Rules restricting certain types of

questionable evidence were abandoned, the threshold for proof of guilt might be

lowered, and perhaps most importantly, limitations On the use of torture could

be ignored. Equally defining of witchcraft was the belief, again never absolutely

uniform but certainly very broadly held, that witches were typically women.

The roots of this notion were extraordinarily diverse, but it too can be seen

to be at least implied in the idea of the sabbath, insofar as sabbaths

emphasized the sexual congress of witches with demons and more basically their

submission and subservience to demonic masters and ultimately to the devil, who

was of course conceived as being male.

Biblical commandments

and classical Aristotelian philosophy both were marshaled to prove that women

were inferior to men spiritually, mentally, and physically, They suffered

weaknesses and corruptions in their bodies, which in Aristotelian thought were

imperfectly formed versions of male bodies, and they were spiritually and

intellectually more vulnerable to the deceptions and seductions of demons. Yet

throughout the early modern era, many authorities largely avoided much

specifically gendered theorizing about witchcraft. If "witch" often

meant "woman" in this period, this seems to have been due less to

abstract philosophy or theology than practical reality. That is, far more women

than men were being accused of witchcraft in the courts. Across Europe an

average of 75 percent of witchcraft accusations focused on women, and in some

regions the percentages rose into the nineties. In Siena , for example, of more

than two hundred witches tried from the late sixteenth to the early eighteenth

century, over 99 percent were women. Certainly one powerful reason for these

percentages was the simple fact that women were, on the whole, far more legally

vulnerable than men in this period, often having no legal status apart from

their fathers and husbands. But the harmful magic that characterized

witchcraft, encompassed issues of fertility-love potions and charms for

potency, but also withered crops, withered male members, and murdered children.

Thus concerns over witchcraft naturally focused on the female domains of

reproduction, childbirth, and nurturing.

While courts could

and did initiate hunts on their own, the vast majority of witch trials

throughout the early modern period responded to charges of simple maleficium brought by ordinary people when, for example, a

cow died or a child sickened unexpectedly. Such occurrences did not

automatically raise suspicions of witchcraft; unexplained misfortune was common

in premodern Europe . Yet if some particular animosity existed between the

victim or the victim's family and another person, and if that person had a

reputation for wielding malevolent magical powers, or if there had been some

direct sign of magical attack, however slight-a muttered curse, a threatening

gesture, or even a baleful stare-then a public accusation might be made.

Authorities, when the accusation was brought to their attention, could add charges

of diabolism, apostasy, and attendance at sabbaths, and wring out confessions

through torture. In 1519, in the city of Metz, in Alsace, the scholar Heinrich

Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486-1535) came to

the defense of an old woman accused of witchcraft by the Dominican inquisitor

Nicolas Savini, arguing that the woman was senile and

deluded, not a servant of Satan. Agrippa was himself a student and practitioner

of learned magic. He wrote a major study, De occulta philosophia (On Occult

Philosophy), when he was twenty-four.

The Protestant

Reformation was, of course, the great event of the early sixteenth century in

Europe. It began in 1517, when Luther circulated his ninety-five theses

challenging basic doctrines of the Catholic Church at the University of

Wittenberg. Within a few years he had moved into an open break with Rome, and

winning broad support across much of the German Empire, he permanently

shattered the religious unity of Western Christendom. The profound political,

social, and religious forces unleashed by the Reformation dominated European

history until well into the next century. That the major period of witch

hunting in Europe corresponded almost exactly to the Reformation era has often

been noted. And much ink has been spilled over whether Catholic or Protestant

authorities executed more witches, but in the end the numbers tell no clear

story. When trials began to rise after 1560, they did so in both Protestant and

Catholic lands. And while religious wars focused on external enemies,

confessionalism directed its energies inward.

The next hundred

years saw the most intense witch hunting, at least in central and western

Europe. For example in the fifty-year period from 1580 to 1630. Fully 90

percent of executions for witchcraft in German lands, which were the heartland

of European witch hunting, occurred in these few decades. In 1589 the suffragan

bishop of Trier, Peter Binsfeld (ca. 1540-1603),

published De confessionibus maleficorum

et sagarum (On the Confessions of Witches), based on

a major series of trials in Trier .

Then in 1595 the

magistrate Nicholas Remy (1530-1612) issued his Daemonolatreiae

(Demonolatry), drawing on his extensive experience with witch trials in the

Duchy of Lorraine. In 1598 the Scottish king James VI (reigned 1567-1625, also

as James I of England , 1603-1625) wrote Daemonologie

(Demonology) after he too had some direct experience with witch trials. In 1599

and 1600 the Jesuit Martin Del Rio (1551-1608) published his massive,

multivolume Disquisitiones magicae

(Investigations into Magic). Henri Boguet (ca.

1550-1619), a magistrate in Franche-Comte who personally executed many witches,

published his Discours des sorciers

(Discourse on Witches).

In 1563, Warhafftige und Erschreckhenliche

Thatten der 63 Hexen (True

and Horrifying Deeds of Sixty-Three Witches), recounting a group of executions

at Wiesensteig, a small principality of around 5,000

inhabitants in the highly fragmented southwestern region of the German Empire.

This pamphlet described the first major hunt in what would become the region of

most intense witch-hunting activity in Europe. That same year, the English

Parliament passed a new act making witchcraft a capital crime, and similarly

harsh legislation was also approved in Scotland . Within only a few years, in

1566, Protestant England had its first known witch trial, although hardly a

major hunt as had occurred in Wiesensteig. At

Chelmsford, in the southeast of England, three women were accused and one was

ultimately executed. In 1590 and 1591 Scottish officials in Edinburgh put on

trial the North Berwick witches, so called because they supposedly gathered at

regular sabbaths at North Berwick , some twenty-five miles east of the capital.

The trials are particularly famous because these witches were accused of

plotting to murder King James VI by raising storms while he journeyed across

the North Sea . James observed portions of the trials, and they may have

inspired the interest in witchcraft that led him to write his Daemonologie.

The most terrible

hunts, however, were those conducted by a handful of German bishops and

prince-bishops In the territory of Trier over 300 people were executed in the

1580s and 1590s. In Maim, major hunts with victims running into the hundreds

erupted every decade from the 1590s through the 1620s. From these Rhineland

archbishoprics, witch hunting spread east along the Main River to the

Franconian bishoprics of Bamberg and Wlirzburg, each

of which experienced major hunts in the 1610’s and 1620’s, as did the Bavarian

bishopric of Eichstatt along with the associated territory of the abbey of

Ellwangen. The absolute worst hunt took place in the Rhineland in the territory

of Cologne, the third of the great German archbishoprics. Here highly organized

and efficient trials from about 1624 until 1634 resulted in the deaths of

probably around 2,000 people.

Yet such gigantic

hunts, were abnormalities. Despite widespread notions of satanic cults and

diabolical conspiracies, most accusations of witchcraft were rooted in specific

cases of perceived harm believed to be wrought through maleficium.

When trials escalated into major hunts, feeding on their own energies, the

situation was different. Inspired by the initial trial, other people might come

forward to make unrelated accusations, magistrates might become convinced that

more witches were hiding in the community and press their own investigations,

and of course accused witches themselves were pressed to name names. Yet even

in these cases, a hunt might well end of its own accord after a certain number

of trials and executions. Officials, comforted that they had uprooted evil from

their region, might stop pursuing their investigations. The community as a

whole, after an initial fearful wave, might grow calmer, and so accusations

would subside. In other cases, of course, this happy release of tension did not

occur. Instead, as accusations and convictions mounted, fear grew, paranoia

might seize courts, and real panic might grip the entire community. In these

situations, accusations multiplied and grew more indiscriminate. That is,

people who did not conform to the stereotypical image of a witch were accused

and arrested. This was certainly the case in Bamberg when the wealthy, socially

respected (and, of course, male) Burgermeister

Johannes Junius was found guilty of witchcraft in 1628.

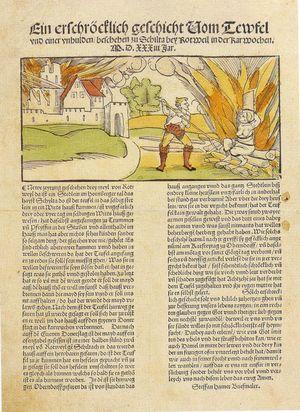

1533 account of the

execution of a witch charged with burning the town of Schiltach

(Baden-Württemberg, Germany)in 1531:

To categorize "

Germany", as the zone of witch hunting par excellence is, however,

somewhat misleading. The situation in the Low Countries was exceptionally

complex. The territories comprising present-day Belgium and the Netherlands

initially lay within the German Empire, but in 1555" Emperor Charles V,

who was also King Charles I of Spain, gave them to his son Philip II of Spain

(reigned 1556-1598). Philip did not, however, succeed his father as emperor

(that title going instead to Charles's brother Ferdinand 1), so the Low

Countries became Spanish rather than imperial territory. In the 1560s and 1570s

these lands saw significant witch trials. Then in 1579, the northern provinces

banded together as the United Provinces of the Netherlands, declaring their

formal independence from Spain in 1581. These provinces also became

predominantly Calvinist, while the southern Spanish Netherlands were Catholic.

In 1592 Philip II issued a decree that extended the right to try witches to

local authorities, and not surprisingly the number of trials in the south (in

what is now Belgium) increased.

Unlike the German

Empire, France had been a unified kingdom for centuries prior to the early

modern period. It did not, however, have exactly the same boundaries as the

modern French state. If we use present-day borders, then " France "

had around 5,000 executions for witchcraft. But this figure shrinks

dramatically if we exclude the eastern regions of Alsace, Lorraine, and

Franche-Comte, which were French-speaking and had significant numbers of

trials, but at this time nominally belonged to the German Empire and were in

fact largely independent. Within its early modern borders, the Kingdom of

France saw fewer than 500 recorded executions for witchcraft. Moreover, as in

the German Empire, so within the Kingdom of France there were important

regional variations.

The Key of Solomon P.2: Occult Science

The

Key of Solomon P.3: Magical Revival

For updates

click homepage here