By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Where earlier we argued that if Homo sapiens somehow could have found a

way to coexist with T. rex, it is unclear which would have become the more intelligent and dominant

species. In some regions, growth-enhancing geography and diversity led to

the rapid adaptation of cultural traits and institutional features to their

surroundings, and the acceleration of technological progress. Centuries later,

this process triggered an outburst of demand for human capital, a sudden drop

in birth rates, and thus an earlier transition to the modern era of growth.

What happend because humans 'did 'survive

whereby for most of this period, successful adaptation generated

progressively better hunters and gatherers, which enabled a rise in the food

supply and a significant increase in the size of the human population.

Eventually, living space and natural resources available per person declined,

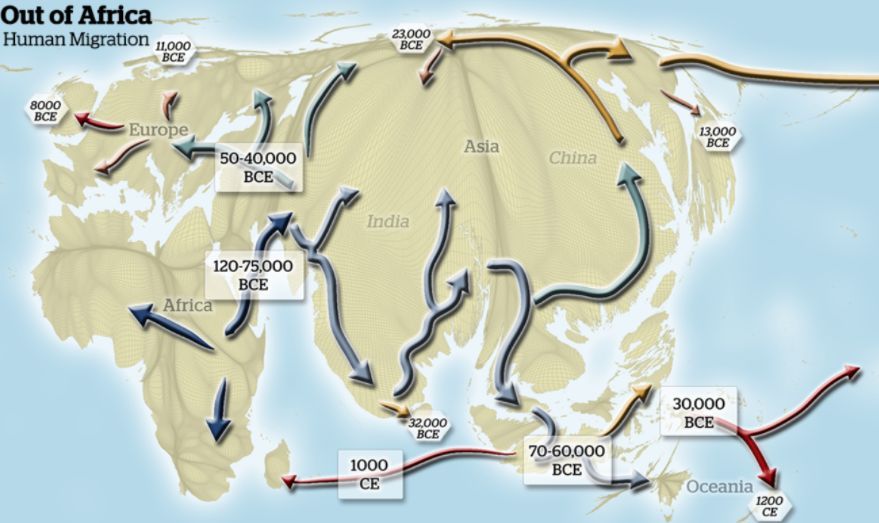

and sometimes as early as 60,000 to 90,000 years ago, Homo sapiens embarked on

a large-scale exodus out of the African continent in search of additional

fertile living grounds. Due to the serial nature of this migratory process, it

was inherently associated with a reduction in the diversity of populations that

settled at greater migratory distances from Africa; the further away from

Africa humans moved, the lower the degree of cultural, linguistic, behavioral,

and physical diversity in their societies.

This phenomenon reflects the serial founder effect. Imagine an island

that is home to five main breeds of parrot – blue, yellow, black, green, and

red – equally well adapted for survival on this island. When the island is hit

by a typhoon, a few parrots have swept away to a deserted, far-flung isle. This

small subgroup is unlikely to contain parrots from all five of the original

breeds. These parrots might be mostly red, yellow, and blue, for instance, and

their chicks – which will soon fill the new island – will inherit their colors.

The colony that will develop on the new island will therefore be less diverse

than the original population. If a very small flock of parrots then migrates

from the second island to a third, that group is likely to be even less diverse

than those in each of the previous colonies. Thus, as long as the parrots

migrate from each parental island more rapidly than the pace of potential

mutations on the island, the further away the parrots migrate (sequentially)

from the original island, the less diverse their population will be.

Human migration out of Africa followed a comparable pattern. An initial

group left Africa and settled in fertile regions nearby, carrying only a subset

of the diversity that existed in their parental African population. Once the

initial migratory group had grown to the extent that its new environment could

no longer support any additional expansion, a less diverse subgroup departed in

search of other virgin territory and settled in habitats further away. During

this human dispersal out of Africa and the peopling of the continents, this

process repeated itself: as populations grew, new subgroups containing only

some of the diversity in their parental colony left again in a quest for

greener pastures. Although some groups switched course, as will become

apparent, the thrust of these migratory patterns was such that groups who left

Africa and reached Western Asia were less diverse than the original human

population in Africa, and their descendants who continued migrating east to

Central Asia and ultimately to Oceania and the Americas, or north-west to

Europe were progressively even less diverse than those who remained behind.

This expansion of anatomically modern humans from the cradle of humankind in Africa

has imparted a deep and indelible mark on the worldwide variation in the degree

of diversity – cultural, linguistic, behavioral, and physical – across

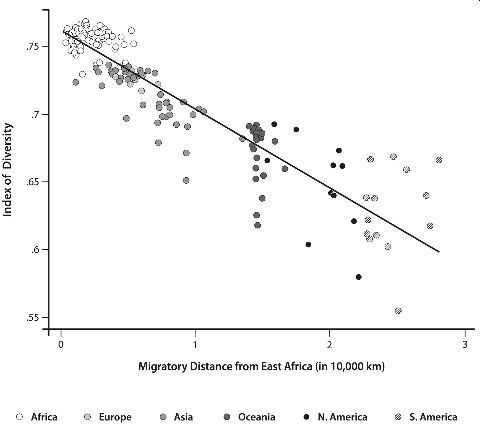

populations This decline in the overall level of population diversity with

migratory distance from Africa is partly reflected in the reduction in genetic

diversity among indigenous ethnic groups at a greater migratory distance from

Africa. Based on a comparable measure of this type of diversity for 267

distinct populations, most of which can be associated with specific indigenous

ethnic groups and their geographical homeland, it is apparent that the most

diverse indigenous ethnic groups are those closest to East Africa, whereas the

least diverse are the indigenous communities of Central and South America,

whose overland migratory distance from Africa is the longest.

This negative correlation between diversity and migratory distance from

East Africa is a pattern that is observed not only across continents. It is

present within continents as well.

Broader evidence for the diminishing levels of diversity among

indigenous groups at a greater migratory distance from Africa comes from the

fields of physical and cognitive anthropology. Studies of particular features

of body shape – for example, the bone structure pertaining to particular dental

attributes, pelvic traits and the shape of the birth canal – as well as

cultural distinctions, such as the differences between the fundamental units of

speech (‘phonemes’) in different languages, also confirm the existence of a

serial founder effect originating in East Africa; again, the greater the

migratory distance from East Africa, the lower the diversity in these physical

and cultural characteristics. Of course, a proper exploration of the impact of

the overall level of population diversity in all its multifaceted forms on the

economic prosperity of nations would require a far more comprehensive measure

than geneticists and anthropologists provide. In addition, it would need to be

independent of the population’s degree of economic development so as to be used

to assess the causal effect of diversity on the wealth of nations. What might

such a measure look like?

Migratory Distance from East Africa and Diversity among Geographically

Indigenous Ethnic Groups:

Conventional measures of population diversity tend to capture only the

proportional representation of the ethnic or linguistic groups in a population.

These measures suffer therefore from two major deficiencies. One is that some

ethnic and linguistic groups are more closely related than others. A society

that consists of an equal proportion of Danish people and Swedish people may

not be as diverse as a society that is composed of equal fractions of Danish

and Japanese. The other is that ethnic and linguistic groups are not internally

homogenous. A nation composed entirely of Japanese people would not necessarily

be as diverse as a nation composed entirely of Danish people. In fact,

diversity within an ethnic group is typically an order of magnitude larger than

the diversity between groups.

A comprehensive measure of the overall diversity of a national

population ought therefore to capture at least two additional aspects of

diversity. First, diversity within each ethnic or subnational group, such as

within the Irish or the Scottish population in the US. Second, the degree of

diversity between any pair of ethnic or subnational groups, capturing, for

example, the relative cultural proximity of the Irish and Scottish populations

of the US in comparison to its Irish and Mexican populations.

In view of the tight negative correlation between migratory distance

from East Africa and diversity in observable traits, these migratory distances

can be used as a proxy for the historical level of diversity in each

geographical location on Planet Earth. We can therefore construct an index of

predicted overall diversity for each national population today, based on the

migratory distance from Africa of their ancestral populations, taking into

account (the relative size of each ancestral subgroup within the country;

the diversity of each of these subgroups as predicted by the distance that their

ancestors traveled over the course of their migration from East Africa; and

(iii) the degree of pairwise diversity between each of these subgroups, as

predicted by the migratory distances between the geographical homelands of the

ancestral populations of each pair.

This statistical measure of predicted diversity has two major virtues.

First, prehistorical migratory distance from East Africa is clearly independent

of current levels of economic prosperity and thus the measure permits the

estimation of the causal effect of diversity on living standards. Second, as

highlighted above, mounting evidence from the fields of physical and cognitive

anthropology suggests that migratory distance from Africa has had an important

effect on diversity in a range of traits that are expressed physically and behaviourally; reassuringly, therefore, the kind of

diversity our measure predicts could affect societal outcomes. Moreover, if the

index measures diversity inaccurately (in a random fashion) – because of a

failure to properly account for internal migration within each of the

continents, for example – statistical theory suggests that this would tend to

lead us to reject, rather than to confirm, the hypothesized impact of diversity

on economic prosperity. In other words, if we are erring, we are erring on the

side of caution.

Finally, it is important to clarify that our measure of diversity is a

societal characteristic. It measures the breadth of variety of human traits

within society regardless of what those traits are or how they may differ

between societies. It, therefore, does not and cannot be used to imply that

some traits are more conducive than others for economic success. Rather, it

captures the potential impact of the diversity in human traits, within a

society, on economic prosperity. In fact, accounting for confounding

geographical and historical factors, it appears that migratory distance from

Africa per se has no impact on the average level of traits such as height and

weight across the globe. It predominantly affects the extent of the deviation

of individuals in the population from this average level.

Armed with this powerful measure of the overall diversity of each

population, we can, at last, explore whether the exodus out of Africa that

occurred tens of thousands of years ago and its impact on human diversity,

might have had an astoundingly long-lasting effect on current living standards

across the globe.

Diversity and Prosperity

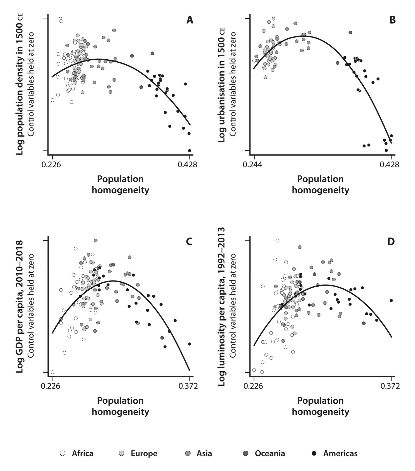

Living conditions in the course of history have indeed been influenced

significantly by levels of diversity and therefore by the migration of Homo

sapiens out of Africa. Migratory distances of the ancestral populations of each

country, or ethnic group, from the cradle of humankind in East Africa, have

generated a persistent ‘hump-shaped’ influence on development outcomes,

reflecting a fundamental trade-off between the beneficial and the detrimental

effects of diversity on productivity at the societal level.

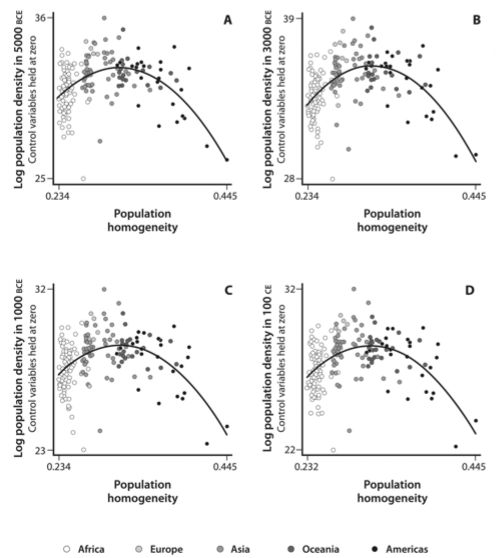

This ‘hump-shaped’ effect of diversity on economic productivity,

whether captured by past levels of population density or urbanization rates, or

current levels of per capita income or night-light intensity (based on

satellite imagery), is both stark and consistent across countries and ethnic

groups. Moreover, these hump-shaped patterns remain qualitatively unchanged

over the 12,000 years since the Neolithic Revolution. Thus, in the absence of

policies that mitigate the cost of diversity in heterogeneous nations and

enhance the level of diversity in homogenous ones, intermediate levels of diversity

have been most conducive to economic prosperity.

In fact, this hump-shaped effect is unique to the impact of ancestral

migratory distance from Africa. Alternative distances, unrelated to the exodus

of Homo sapiens from Africa and to human diversity, do not generate similar

hump-shaped patterns. In particular, aerial distance from East Africa, as

opposed to migratory distance, is uncorrelated with economic prosperity, which

is reassuring, since prehistoric humans migrated out of Africa by foot rather

than by airplane. Furthermore, migratory distances from ‘placebo origins’ –

other focal points on Planet Earth from which Homo sapiens has clearly not

emerged – London, Tokyo, or Mexico City – do not have any effect on economic

prosperity. Nor is this relationship-driven by geographic proximity to leading

technological frontiers in the distant past, such as the Fertile Crescent.

Separate bodies of evidence confirm the proposed mechanism behind this

intriguing result: namely, that societal diversity has indeed exerted

conflicting effects on economic well-being. On the one hand, by widening the

spectrum of individual values, beliefs, and preferences in social interactions,

the findings suggest that diversity has diminished interpersonal trust, eroded

social cohesion, increased the incidence of civil conflicts, and introduced

inefficiencies in the provision of public goods, thus adversely affecting

economic performance.[16] On the other hand, greater societal diversity has

fostered economic development by widening the spectrum of individual traits,

such as skills and approaches to problem-solving, thus fostering

specialization, stimulating the cross-fertilization of ideas in innovative

activities, and facilitating more rapid adaptation to changing technological

environments.

The top panels depict the impact of predicted population homogeneity on

economic development as reflected by either population density (Panel A) or

urbanization rate (Panel B). The bottom panels depict the impact of predicted

ancestry-adjusted homogeneity on economic development in the contemporary era,

as reflected by either income per capita during the 2010-18 time period (Panel

C) or luminosity per capita during the 1992–2013 time period (Panel D).

This figure depicts the impact of observed population homogeneity of

geographically indigenous ethnic groups, as predicted by migratory distance

from Africa, on long-run historical economic development, as reflected by

population density in 5000 BCE (Panel A), 3000 BCE (Panel B), 1000 BCE (Panel

C) and 100 ce (Panel D).

Furthermore, the ‘sweet spot’ level at which diversity is most

conducive for economic prosperity has increased in the past centuries. This

pattern is consistent with the hypothesis that diversity is increasingly

beneficial in the rapidly changing technological environments that have been

characteristic of advanced stages of development.[20] This growing importance

of diversity in the development process sheds new light on the causes of

China’s and Europe’s reversal of fortunes. In the year 1500 CE, the level of

diversity most conducive to development existed among nations such as Japan,

Korea, and China. Evidently, their relative homogeneity fostered social

cohesion more than it stifled innovation and was ideal in the pre-1500 era when

technological progress was slower and the benefits of diversity, therefore,

more limited. Indeed, China prospered greatly in the pre-industrial era. But as

technological progress accelerated over the subsequent five centuries, the

relative homogeneity of China appears to have delayed its transition to the

modern era of economic growth, transferring economic dominance to the more

diverse societies of Europe and subsequently North America. The level of diversity

most advantageous for economic development in the modern era is now closer to

the current level of diversity in the United States.

Human diversity is of course just one of the factors that have affected

economic fortunes, and proximity to the ‘sweet spot’ of population diversity

does not ensure prosperity. Nevertheless, accounting for geographical,

institutional, and cultural characteristics, diversity retains a considerable

effect on the economic development of countries, regions, and ethnic groups in

the present, just as in the past. The significance of these effects is

particularly extraordinary given the eons that have passed since Homo sapiens

first stepped out of Africa – and it can be quantified. About a quarter of the

unexplained variation in prosperity between nations, as reflected in average

income per capita during 2010–18, can be attributed to societal diversity. By

comparison, using the same methods, geo-climatic characteristics account for

about two-fifths of the variation, the disease environment for about

one-seventh, ethnocultural factors account for one-fifth, and political

institutions account for about one-tenth.

Yet, despite human diversity being such a powerful determinant of

prosperity, the fate of nations is not carved in stone. Quite the contrary: by

understanding the nature of that power we can design appropriate policies to

foster the benefits of diversity while mitigating its adverse effects. If

Bolivia – which has one of the least diverse populations – would foster

cultural diversity, its per capita income could increase as much as five-fold.

In contrast, if Ethiopia – one of the world’s most diverse countries – were to

adopt policies to enhance social cohesion and tolerance of difference, it could

double its current income per capita.

More generally, much could be achieved through education policies aimed

at making the best use of the levels of diversity that already exist, with

highly diverse societies seeking to promote tolerance and respect for

difference, and highly homogeneous ones encouraging openness to new ideas,

skepticism, and a willingness to challenge the status quo. In fact, any

measures that successfully enhanced pluralism, tolerance, and respect for

difference would further elevate the level of diversity that is conducive to

national productivity. And given the likelihood that technological progress

will intensify in the coming decades, the advantages of diversity in societies

that are able to foster social cohesiveness and mitigate its costs are only set

to grow.

The Grip of the Past

The impact of human diversity on economic development may be the most

striking example of how modern variations in the wealth of nations are rooted

in complex factors originating in the ancient past. In fact, readers in urban

pockets of the developed world with large migrant populations might find it

surprising that the distribution of human diversity has persisted for quite so

long across large segments of the planet. Institutional and cultural

differences between countries have diminished in the modern era, as developing

countries have tended to adopt the advantageous political and economic

institutions of developed nations, and individuals have sought to emulate

beneficial cultural norms. Likewise, some adverse effects of geography, such as

disease prevalence or lack of access to the sea, have been mitigated by

technological progress. And yet, largely due to the inherent attachment of

individuals to their homelands and their native cultures, as well as the

presence of legal barriers to international migration, human diversity in some

regions in the modern era has changed at a much slower pace.

Thus, in the absence of proper inducements – educational,

institutional, or cultural – highly diverse societies are likely to struggle to

achieve the trust and social cohesion levels needed for economic prosperity,

while homogeneous ones will fail to benefit sufficiently from the intellectual

cross-pollination on which technological and commercial progress relies. The

income gap between nations may therefore endure despite the convergence of

institutional and cultural traits across them. Such is the grip of the

past.

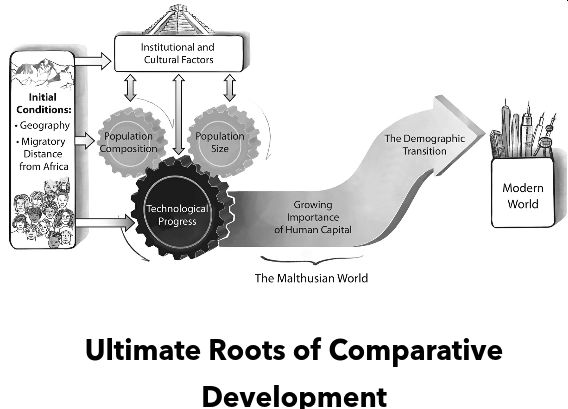

Since the first bands of Homo sapiens walked out of Africa millennia

ago, their societal characteristics and the distinct natural environments they

settled have been dissimilar, and the effects of those dissimilarities have

persisted over time. Some were blessed at the outset with human diversity

levels and geographical attributes that were conducive for economic

development, while others faced less favorable initial conditions that have

been detrimental to their growth process ever since. Favorable initial

conditions contributed to technological progress and led to the adoption of

growth-enhancing institutional and cultural characteristics – inclusive

political institutions, social capital, and future-oriented mindset – further

stimulating technological progress and the pace of the transition from

stagnation to growth. Unfavorable endowments, by contrast, dictated slower

trajectories, reinforced by the adoption of institutions and cultural

characteristics that hindered growth. Although throughout our history

institutions and cultures have been greatly influenced by geographic

characteristics and human diversity, they have also remained susceptible to

abrupt historical fluctuations that occasionally sway the fates of nations. As

in the case of North and South Korea, living standards may differ sharply even

between countries that share both their geography and population diversity. In these

infrequent instances, cultures and institutions could be the leading forces

behind the observed gaps across some nations.

However, the long arc of human history reveals that geographical

characteristics and population diversity, formed partly during the migration of

Homo sapiens from Africa tens of thousands of years ago, are predominantly the

deepest factors behind global inequalities, while cultural and institutional

adaptation has often dictated the speed at which development progressed in

societies across the globe. In some regions, growth-enhancing geography and

diversity led to the rapid adaptation of cultural traits and institutional

features to their surroundings, and the acceleration of technological progress.

Centuries later, this process triggered an outburst of demand for human

capital, a sudden drop in birth rates, and thus an earlier transition to the

modern era of growth. Elsewhere, this interaction set societies on a slower

journey, delaying their escape from the jaws of the Malthusian beast. Thus

emerged the extreme global disparities of the modern world.

For updates click hompage here