Protesters wearing

pink and yellow armbands succeeded in ousting the regime of Kyrgyz President

Askar Akayev, overtaking the presidential palace in

Bishkek early March 24. Akayev and his family reportedly

fled by helicopter to Russia.

The fall of Akayev's pro-Russian regime, in what has been dubbed the

"Tulip Revolution," could be viewed as yet another blow for Moscow in

its near abroad, where a series of pro-Western "velvet" revolutions

have been steadily shrinking Russia's sphere of influence. Now, it is not clear

that what has occurred in Kyrgyzstan is indeed a pro-Western revolution. The

opposition is hardly a unified movement: Clan affiliations, ethnic divisions

and other internal demographics are all in play. And, as some have noted, the

fact that demonstrators have been unable to settle on a common color for their

armbands does not bode well for consensus on larger political matters.

Recognizing that a

forecast for political upheaval in Central Asia does not necessarily draw

screaming headlines, it is important to remember a few geographic facts.

Kyrgyzstan is nestled high in the Tien-Shan Mountains, bordering China on its

south and east. And, as a former part of the Soviet Union, it remains of

strategic interest to Russia. What makes all of this particularly interesting

is that both Russia and China have a tendency to view any upheaval in regions

where they take interest as part of a conspiracy orchestrated by the United

States in order to challenge their hegemony.

This might be

paranoid thinking. It might be prudent "worst-case scenario"

planning. Or it might be a rational appreciation of Washington's intentions.

Whichever it is, the simple fact is that both regional powers regard any

instability in any country in the area as being generated by the United States

and intended to harm them.

Because Kyrgyzstan is

part of the Muslim world, the United States certainly cannot afford to be

indifferent to anything that happens there. U.S. forces are still conducting

operations in Afghanistan and probing into Pakistan's northern provinces -- and

supplying its forces there from a logistics base in Kyrgyzstan. That base is

one of two interests Washington has in Kyrgyzstan; the other is making certain

al Qaeda or other radical Islamist groups don't increase their power in the

region. So it would stand to reason that Washington has no interest in

fostering instability in Kyrgyzstan.

The Russians are not

so sure. They see the United States turning its attention from al Qaeda to

other issues, and they don't buy the Bush administration's line that its

political involvement in the region -- specifically in Ukraine, where

Washington helped secure a win by pro-Western President Viktor Yushchenko late

last year -- is simply about the American love for free elections. They believe

the United States sought to install a pro-U.S. government in Kiev in order to

bring Ukraine into NATO and undermine Russian national security.

Russian leaders also

see the United States as locking down its power in Central Asia. The United

States, having exerted influence in the region initially for economic

development, had Russia's support when it introduced troops following the Sept.

11 attacks. Leaders in Moscow and elsewhere think the Americans now are using

these troops to create a strategic reality: denying Russia its sphere of

influence in the region. They think Kyrgyzstan is part of this strategy.

On the other side of

Asia is China. Its westernmost province, Xinjiang, is predominantly Muslim and

in rebellion against Beijing. Chinese leaders have never been comfortable with

the American position on Xinjiang -- which seemed to argue that the U.S. war

against al Qaeda was one thing, but that China's battle against Muslim

separatists in Xinjiang was quite another. Government officials occasionally

have indicated a belief that the Americans actually liked the Xinjiang

insurrection because it weakened China.

The Chinese are

concerned that instability in Central Asia will increase the flow of supplies

to Xinjiang militants. Therefore, they view events in Kyrgyzstan as part of

Washington's strategy to threaten China, at a time when Washington has

pressured Europe to back away from arms sales to Beijing. The Chinese don't

believe the United States is obsessed with al Qaeda any longer. They believe

the Americans are obsessed with China, and they see events in Kyrgyzstan as a

security threat.

Washington did not

engineer the Kyrgyzstan rising, but it can use the uprising to increase its

influence in Central Asia. The world has changed sufficiently that al Qaeda is

no longer the top story; relationships among great powers are.

In fact on Oct. 11

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice first arrived in Kyrgyzstan for the start

of a regional tour that includes plans for stops in Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and

Afghanistan. She is calling for political change in the region, but the U.S. is

more concerned with having Central Asian governments help in its war against

militant Islam than in providing security assistance for these governments at

home.

With respect to the

former Soviet republics, Rice has said that the purpose of her visit will not

be to push for military bases, as has been the case with other recent

high-level U.S. visits to the region, but to promote democracy and regional

economic development.

Rice's statement

constitutes a change of tune for the United States in the region and is

indicative of efforts by Washington to reverse its decline of influence in the

region since the May uprising in Uzbekistan and the reinvigoration of the

Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in July.

Washington's efforts

in recent months to secure its military bases in the region and to find

substitutes for its soon-to-be-lost Karshi-Khanabad Air Base in Uzbekistan

smacked of self-interest to Central Asia's governments - which have economic,

political and security interests of their own that are strikingly different

from Washington's. During this same period, Moscow strengthened economic ties

(via a merging of the Central Asia Cooperation Organization and the Eurasian

Economic Union) resulting in an upgrade of infrastructure ties. In other words

Russian investments create employment and serve economic needs.

Hence all three

Central Asian countries are merely speaking politely and offer gestures of

friendship during Rice's visit - but nothing of substance will change, and U.S.

influence will continue to decline in the region to the benefit of Russia in

this new phase of the Great Game.

The Sept. 19-24

Russo-Uzbek military exercises in Uzbekistan are just one of many signs that

the "Great Game" in Central Asia is intensifying as Washington faces

Moscow and Beijing's combined strength.

Central Asia: Why The 'Great Game' Heats Up

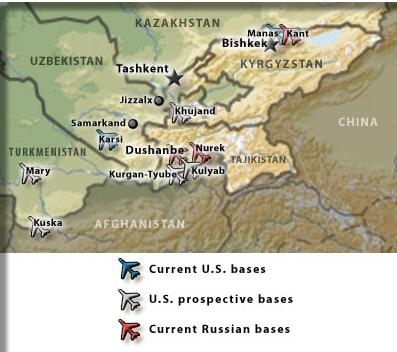

A key element in the

"Great Game" is outside powers' security presence -- whether bases or

joint exercises with host countries or arms deliveries -- in the region.

Geopolitically, a security presence allows an outside power to exercise more

control over a host country's policies and make sure the outside power's

national interests are observed and promoted in the host country. Economically,

a security presence allows an outside power to ensure that Central Asia's

energy riches are exported in the direction the outside power wants; the

outside power can also make sure such deliveries are safe and that other

outsiders cannot easily reroute the region's energy outflow. In

military-strategic terms, a security presence allows an outside power to

project forces and power from a host country to other countries in the region,

including the outside power's rivals.

Uzbekistan

Moscow and Beijing’s

positions in Uzbekistan are strong, and will grow stronger in the near future.

Knowing well that Washington is working to overthrow him – most likely through

a popular uprising such as the Andijan uprising in May, in which pro-Western

and Islamist elements joined forces – President Islam Karimov quickly is

developing military, political and energy ties with Moscow and Beijing, which

Karimov sees as capable protectors.

The latest sign of a

growing Russo-Uzbek alliance is the Sept. 19-24 joint counterterrorism

exercises. The goal is to train Russian and Uzbek forces together to quickly

put down an armed rebellion in Uzbekistan similar to the Andijan uprising but

larger in scale, Uzbek military sources said. Through the Shanghai Cooperation

Organization (SCO), Tashkent is entitled legally to receive such help from

Moscow – and from Beijing, for that matter. Two paratrooper companies from the

76th Russian Airborne Division and several special forces groups

from the Russian General Staff’s Main Intelligence Directorate are

participating along with the same number of Uzbek paratroopers and special

forces groups. To emphasize the exercises’ importance, the two nations’ defense

ministers are attending.

The exercises are

being held in the Jizzax region, about 170 miles

southwest of Tashkent, in the foothills of mountains. The terrain is similar to

that of the volatile Fergana Valley, where the next Uzbek uprising is most

likely. The Jizzax region itself has become restive,

with Islamists and pro-Western activists fomenting anti-government sentiments

and with some Jizzax clan leaders suspected of

participating in a power struggle against Karimov.

Kazakhstan

Kazakh President

Nursultan Nazarbayev, concerned with the prospect of a pro-U.S.

"revolution" that could remove him from power, is moving closer to

both Moscow and Beijing. This is especially true in the fields of politics and

security; in addition to worrying about a "revolution," Nazarbayev

sees his country facing a real threat from international and domestic Islamist

militants and he realizes that Moscow and Beijing -- not Washington -- can give

him quick and efficient help. Though Kazakhstan has been increasing its

military cooperation with the United States regarding the Caspian Sea, that

cooperation only involves U.S. funding for new maritime equipment and is

significantly smaller in scope and depth than Kazakhstan's cooperation with

Russia and Astana's SCO commitments. Economically, Astana is bent on customer

diversification and is working with Western, Russian and Chinese companies.

Astana's closer

relationship with Beijing was evidenced when visiting Chinese Defense Minister

Cao Gangchuan and his Kazakh counterpart Danial

Akhmetov agreed Sept. 19 that their countries' and agencies' military

cooperation should be strengthened. Kazakh defense sources say the two

ministers discussed joint high military staff consultations, Kazakh officers' training

in Chinese military academies and proposals from the Kazakh defense complex to

develop modern-arms systems for China.

The latest example of

growing Kazakh-Russian security collaboration is a joint counterterrorism

exercise that Kazakhstan's Pavlodar regional police department and Russia's

Novosibirsk regional police conducted Sept. 13. The exercises, located in the

Kazakh town of Karasuk on the Kazakh-Russian border,

included a scenario in which terrorists took hostages and special forces troops

stormed the hideout and released the hostages. Kazakh and Russian joint

counterterrorism training has intensified vastly in the last couple of years, with

police forces alone conducting 13 exercises. Kazakhstan is concerned with

Islamist militants training in its southern areas to stage attacks against

energy infrastructure, while Russia is concerned with jihadists coming from

Central Asia to implement terrorist attacks within Russia.

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan offers a

curious example of how geopolitics can play tricks with expectations. The Bush

administration thought Kyrgyzstan’s pro-Western “revolution” in April would put

the country squarely in the U.S. sphere of influence. Bishkek is maintaining

good ties with Washington – for example, Kyrgyzstan still hosts the United

States’ Manas Air Base – but recent developments show the government is

drifting further toward Moscow and, to an extent, Beijing. The underlying

reason for this is that no matter what clan is in power, members of the Kyrgyz

elite feel a pressing need to protect their personal and national security

against Islamist militants and civil disturbances, and it knows U.S. troops

from Manas are unlikely to interfere if a new uprising occurs, though Beijing

and especially Moscow will be ready and able to oblige for their own interests.

The future of Manas

Air Base is coming into question. On Sept. 21, Kyrgyz President Kurmanbek

Bakiyev said Washington should pay a higher rent for the base and withdraw from

Kyrgyzstan once the situation in Afghanistan stabilizes. Bakiyev said the terms

and conditions of the lease agreement and current rent amount should be

reviewed and were discussed when U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld toured

Central Asia in July.

During a visit to

Kyrgyzstan, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov said Sept. 21 that Moscow is

set to invest several billion rubles in a long-term program for its air base at

Kant. Ivanov’s announcement came as he signed an agreement with Kyrgyz Defense

Minister Ismail Isakov to provide Kyrgyzstan with $3 million in military aid

consisting of dozens of Kamaz trucks, an Mi-8 Hip helicopter, firearms and

spare parts for support vehicles and armored vehicles. By providing the aid,

Moscow is fulfilling Bishkek’s wish list. In a mountainous country such as

Kyrgyzstan, helicopters are very useful for transportation and logistical

support – and would facilitate support operations in the hills away from

Kyrgyzstan’s towns and cities, where Bishkek’s control over the locals is

tenuous at best. One feature of the Mi-8 is that gun pods and 57 mm unguided

rocket pods can be mounted on the helicopter easily; thus a transport

helicopter can be turned into a gunship. Also, armed with aging Soviet-made

weapons and equipment, the Kyrgyz army needs spare parts from Russia.

Tajikistan

The Tajik government

is balancing carefully between Moscow and Washington, with Russia maintaining a

military base at Dushanbe and the United States hoping to get one to three air

bases in the country to partly substitute for the loss of the large Karshi-Khanabad

Air Base in Uzbekistan. Because some key Tajik officials could be under the

influence of drug lords -- who are extremely powerful in Tajikistan and want to

push Russia out of the country because Russian security forces interfere with

their drug-trafficking operations that run from Afghanistan to Russia and

Europe -- Tajikistan could tilt toward Washington.

There already are

signs that Dushanbe is leaning toward the United States; on Sept. 16, a senior

official in Tajikistan's ruling People's Democratic Party said Dushanbe is

willing to host some of the U.S. military equipment and personnel that will

have to leave Uzbekistan by early 2006. The statement indicates that Washington

is having some success in its response to Russia and China's concerted efforts

to roll back U.S. influence in Central Asia.

Turkmenistan

Turkmen President

Saparmurat Niyazov traditionally keeps both Moscow and Washington at bay.

Turkmenistan has been officially neutral since independence. Siding with either

Moscow or Washington would shift the way that all of Turkmenistan's neighbors

see the country and would force them all -- particularly Iran and Uzbekistan --

to reconsider their regional postures and strategic positions.

Niyazov so far has

not allowed the United States to establish bases in his country, but he also

has refrained from aligning firmly with Moscow by keeping Turkmenistan from

joining security alliances with Russia or the SCO. Niyazov is not overly

friendly toward the West, either, fearing the possibility of a pro-Western

"revolution" in Turkmenistan. Despite Niyazov's attitude, Washington

has been making overtures toward Ashgabat.

Gen. John Abizaid,

commander of U.S. Central Command, visited Turkmenistan and Tajikistan in

August in an effort to secure alternative bases after the U.S. leaves Manas and

Karshi-Khanabad. Though U.S. and Turkmen officials denied the visit had

anything to do with bases, it is difficult to otherwise explain Abizaid's

visit; when he was busy commanding U.S. forces in Afghanistan and Iraq, Abizaid

was not likely to go to Ashgabat with less meaningful goals in mind. German

media reported that Washington was seeking bases in Turkmenistan and that

Niyazov agreed to accept them in exchange for Washington's promise not to try

to overthrow him. Russian intelligence sources say that agreement has not yet

been made.

One of the Turkmen

bases Washington reportedly is looking at is Mary, near the Iranian border. The

former Soviet base was used heavily during the 1979-1989 Afghan war to stage

Soviet bombing missions, and it has a long runway capable of accommodating large

transport aircraft and strategic bombers. With some upgrades, the base at Mary

would make an excellent regional logistics hub to support U.S. operations in

Afghanistan and elsewhere in Central Asia. The base's proximity to Iran cannot

have gone unnoticed; Washington knows that having a large U.S. presence on a

third border will give Tehran something to worry about.

The other Turkmen

base Washington is looking at is at Gusgy, on the

Afghan border. During the Afghan war, Soviet troops used the border crossing

there as a main transit point into Afghanistan, and there is still a small

Turkmen-maintained air base there.

It remains to be seen

whether Niyazov will allow U.S. forces into his country, or if the U.S.

requests will be used only to further his policy of playing both sides of the

fence between Washington and Moscow, though the latter is more likely. Overall,

with the question of U.S. bases in Central Asia still unanswered, much of the

"Great Game" still lies ahead.

KYRGYZSTAN

Askar Akayev became president in 1990. He was re-elected by

direct popular vote shortly after independence in 1991 and again in 1995 and

2000. In the early years of his presidency, Mr Akayev was widely regarded as the most liberal leader in

former Soviet Central Asia. But there was growing discontent with his

leadership, amid reports of political suppression, economic stagnation and

widespread corruption.

Analysts have

expressed surprised at how quickly institutions collapsed in Kyrgyzstan, and

the speed at which Mr Akayev

lost control of government. They say the fall of the regime is an indication of

its weakness, rather than the opposition's strength.

Observers says

Kyrgyzstan's political future depends on how well the opposition is able to

develop. At the moment, many personalities and interests are jostling for

power, and it is not entirely clear what they stand for.

KAZAKHSTAN

Kazakhstan is the

wealthiest and most stable country in Central Asia thanks to its oil reserves,

but the political system has become increasingly authoritarian, corruption is

widespread and rural areas are still very poor.

Political power is

concentrated in the hands of Nursultan Nazarbayev, who came to power in 1989 as

the communist leader of Soviet Socialist Republic and has been president since

1991. His party has a comfortable parliamentary majority, ensuring he maintains

tight control. Like some other Central Asian rulers, Mr

Nazarbayev has been keen to promote his relatives and allies.

Previous elections

have failed to meet international standards. Privately owned and opposition

media are subject to harassment and censorship.

Analysts say the country

is relatively stable in the short term. However, the small opposition is

increasingly active, and oil wealth has created a business class that is

interested in political power. Presidential elections are slated for 2006.

TAJIKISTAN

Tajikistan is the

only Central Asian country to have had a civil war since the break-up of the

Soviet Union. The five-year conflict, from 1992-1997, killed up to 50,000

people, and more than one-tenth of the population fled the country.

Emomali Rahmonov was

elected president in 1994. His People's Democratic Party occupies almost all of

the 63 seats in the lower house of parliament. Previous elections have failed

to meet international standards. Opposition Islamic and communist parties have

a handful of seats between them.

The main issues that

dog Central Asia - widespread poverty and repressive leadership - are of

concern here, too. While Mr Rahmonov has experienced

serious challenges to his rule, observers say the opposition is weak and

divided, and that the government is increasingly authoritarian.

Tajiks are still

"war-weary", one observer says, and unwilling to take risks. However,

the country's economy is increasingly reliant on revenues from its position as

a drugs route out of Afghanistan, and there continue to be simmering divisions

related to the civil war.

TURKMENISTAN

Turkmenistan is

effectively a one-party state, and the regime is considered highly

authoritarian and repressive. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, head of

the Communist Party Saparmyrat Niyazov was elected president in 1991, and named

president-for-life in 1999. Mr Niyazov has nurtured a

personality cult and likes to be known as Turkmenbashi,

or Father of All Turkmens.

There is no official

political opposition. There is no free press, and only a handful of opposition

demonstrations have been reported since independence. A small number of

fractured opposition groups exist in exile, but their influence is said to be

negligible.

Analysts are

concerned about the country's growing poverty - despite revenue from important

reserves of natural gas - and the absence of political institutions. The lack

of a clear line of succession after Mr Niyazov is a

potential cause of instability in the longer term.

UZBEKISTAN

The political leadership

has been dominated by Islam Karimov since 1989, when he became Communist Party

leader in then Soviet Uzbekistan. The regime is

unpopular. There is no real internal opposition and the media is tightly

controlled by the state. A UN report has documented the systematic use of

torture. There is widespread frustration about the country's low standards of

living.

A series of bomb

blasts in 1999 was blamed on Islamic extremists, who were accused by the regime

of seeking to destabilise the country. Mr Karimov has been accused of using the perceived threat

of Islamic militancy to justify his repressive style of leadership, and

observers say that has strengthened sympathy for militant groups.

The absence of a

legitimate means of expressing dissent could create fertile ground for violent

protest. Mr Karimov will be watching developments in

Kyrgyzstan very carefully, and is expected to intensify efforts to stifle any

potential spread of "people power".

For updates

click homepage here