Paracelsus’s ideas

were of a strong influence on the very first

Rosicrucian book ever written.

(See among others “The Magic Flute” by M.F.M. van den Berk, 2004.) Although

there were certainly those with sympathies for what they apparently believed

was a real society; it is not clear that there were any actual Rosicrucians and modern scholars agree that the whole thing

was a hoax which, caught on. In other words what's interesting is not that

there weren't any Rosicrucians, but that people cared

whether there were or weren't, and wanted there to be. And an emphasis on

Hermetic origins seems to have gained prominence in Paracelsian

literature during the second half of the sixteenth century.

The popular

Psychologist Carl G. Jung Jung describes Paracelsus

as “a pioneer of empirical psychology and psychotherapy”, and makes mention of

the post-Paracelsus emergence of a “fantastic species of literature”.

And where the above

period is termed that of the (non-existant)’ older’ Rosicrucians the later period termed that of the ‘later’ Rosicrucians had very well living people among its

creations. For example Hermann Fictuld (a

correspondent with the theosopher Friedrich Christoph

Oetinger, 1702-1782), is seen as one of the founders of what later came to

be known as the Gold- and Rosenkreutz a quasi Masonic order. In fact following the collapse due to

scandal of Baron von Hund's `Strict Observance' Knights Templar strain of

Freemasonry in 1782, the Gold- and Rosenkreutz even

became the dominant force within the German Craft, alongside the Bavarian

'Illuminati' (also largely influenced by the idea of early Rosicrucian’s).

The Gold- and Rosenkreutz was marked by its anti-Enlightenment stance and

its emphasis on Christian piety and alchemy. Alchemical ideas and symbols were

incorporated into the rituals of initiation and the teachings that accompanied each

grade; laboratory alchemy was also an important part of the work of the order

from the third degree onwards, and those members reaching the seventh grade

were deemed to have knowledge of the Philosophers' Stone.Paracelsian

and Valentinian alchemy were the order of the day, although there were some

members who denied the tria prima of Paracelsus.

In the work that has

been described as the `Bible' of the Gold- and Rosenkreutz

Order, the Compass der Weisen (1779), we find an

extensive survey of alchemical and Rosicrucian writings, compiled by a frater Roseae et Aureae Crucis with the

partial aim of making them comprehensible within the context of Freemasonry.

The author names a number of early modern writers as authorities, including

Michael Maier, Heinrich Khunrath, Robert Fludd, Thomas Vaughan, Gerhard Dorn, Basil Valentine and

Adrian von Mynsicht. The introduction deals with the

occult knowledge of the Egyptians.

Alchemy itself was

originally an offshoot of the decorative arts, whose practitioners had begun in

late antiquity to view their products in Pygmalion-like fashion as

replications, rather than representations, of the natural world. Always aware

of the potential charge that they too were engaged in a sort of trompe l'oeil

trickery, the medieval and early modern alchemists explicitly claimed that

their discipline perfected nature rather than merely imitating it. This view

built on the distinction that Aristotle draws in the Physics (11 8 199a15-17),

where he states that "the arts either, on the basis of Nature, carry

things further (epitelei) than Nature can, or they

imitate (mimeital) Nature. To alchemical writers,

this meant that most other fields leading to physical production, such as shipbulding, fabric making, and the visual arts, merely

mimicked natural products-either in a loose and general sense, as in the old

stories that based the invention of architecture on the observation of

swallows' nests and weaving on the activity of spiders, or in the specific

sense that pertained to painting, sculpture, and other representational arts.

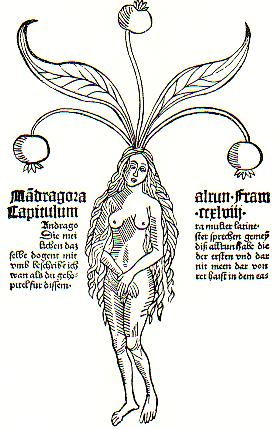

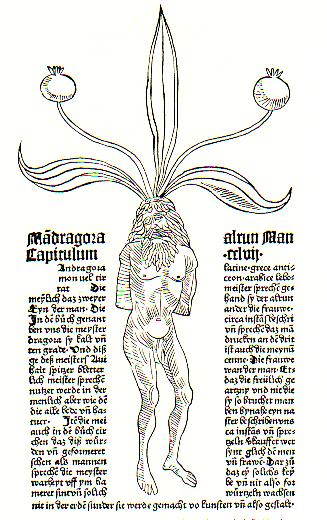

The Mandrake,

or Alraun, -root of German folk legends was the

probable the source for an idea even the founder of Scientology attempted

to manifest (and his fellow Aleister Crowley student)

, that of creating a ‘Homunculus’ or ‘moon child’.( Paracelsus,

De natura rerum, in Sudhoff, 11:348-349. See p. 349:

"ein ding sein form und gestalt ganz und gar sol verlieren und zu nicht werden und aus nichts widerumb etwas, das hernach vil

edler in seiner kraft und rugent dan

es erstlich gewesen ist.")

The Mandrake/Alraun root was visualized to look like a little

human, and was often kept in a bottle or flask at the time, and is strikingly

reminiscent of the homunculus found in the pseudo-Paracelsian

De natura rerum. Also in medieval times there where already speculations on

incubi and succubi to produce an image of the

artificial man excelling over normal humans in intelligence, strength. The

author of the De natura rerum however inserted the alchemical paragon of human

art into this preexisting framework by now claiming that by incubating a flask

at moderate heat, one can isolate the male seed from the female and so produce

a transparent, almost bodiless homunculus. See, Joachim Telle,

"Kurfürst Ottheinrich, Hans Kilian und Paracelsus: Zum pfälzischen Paracelsismus im 16. Jahrhundert," in Von Paracelsus

zu Goethe und Wilhelm von Humboldt, Salzburger Beiträge zur Paracelsusforschung

22 (Vienna: Verband der Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaften Osterreichs,

1981),130-146; R.J. W Evans, Rudolph II and His World (Oxford: Clarendon Press,

1973);Jost Weyer, GrafWolfgangll von Hohenlohe und

die Alchemie(Sigmaringen:J. Thorbecke,

1992); Bruce Moran, The Alchemical World of the German Court (Stuttgart:

Franz Steiner, 1991).

Or as William R.

Newman recently concluded; Paracelsus argues that the mandrake incorrectly

described by necromancers and philosophers is really a homunculus, which they

have misidentified. Paracelsus is probably thinking here of the old German folk

legend that the Alraun (alreona)

grew primarily beneath gallows, where it was generated from the sperm or urine

of hanged criminals: in honor of its provenance, the Alraun

was also called Galgenmann or Galgenmännlein

("gallows man"). This belief has been traced back to Avicenna and is

mentioned by early modern German authors such as Brunfels.

In the seventeenth century it was still believed in some quarters that such a

gallows man could also be produced by burying the sperm of a young man

underground and periodically feeding the developing embryo with more of the

same." In order to understand Paracelsus's reasoning in the above passage,

one must realize that he customarily employs the expression venter equinus, a technical term in alchemy for decaying dung used

as a heat source, to mean any source of low, incubating heat. Thus it was easy

for him to interpret the mandrake legend as a garbled recipe for the

homunculus, where the earth beneath the gallows acted as a venter equinus or incubator (Newman, Promethean Ambitions, 2004,

p. 215).

The homunculus,

moreover, was closely tied to the issue of palingenesis, the artificial rebirth

of living things by chymical means, which enjoyed a

widespread religious significance in the seventeenth century. As we noted

before, the De natura rerum of pseudo-Paracelsus refers to the

"clarification" of a bird by combustion to ash which is in turn

allowed to ferment into a "mucilaginous phlegm." The rebirth of the

clarified bird from this phlegm is evidently a naturalistic explanation of the

ancient Phoenix myth. The De natura rerum links this process explicitly to the

making of the homunculus. Directly after the recipe for the clarified bird, the

text says the following: "One must also know that people may be born thus

without natural father and mother." The homunculus recipe too involves the

use of a mucilaginous phlegm, although in its case this substance is provided

by a living human donor rather than being produced from ash. Both in the case

of the artificial bird and in that of the artificial human, the phlegm is

allowed to putrefy in an alchemical flask, which must be tended by a spagyrist

(chymist).

The theme of rebirth

appears again in the sixth book of the De natura rerum, with the extravagant

story of Virgil's failed experiment that is used to support the regeneration of

dissected snakes. The end of this book carries the process of resuscitation

into another area as well, that of the vegetable world. Pseudo-Paracelsus

claims that wood must be burnt to ash and then placed into a vessel along with

the "resin, liquor, and oiliness" (resina, liquore,

and oleitet) of the same tree. The chymist should then allow this to putrefy into a

mucilaginous material as in the case of the incinerated bird, again with a mild

heat. Within this slimy substance}the three Paracelsian

principles exist-mercury, sulfur, and salt-in the form of the watery moisture

that evaporated from the burning wood, the flammable oil that it released

during combustion, and the salt that was left after the conflagration was over.

In order to regenerate the tree from its principles, one need only pour the

putrefied material into a suitable soil, upon which the tree will grow again,

but nobler and more vigorous than before. From this phenomenon the author of

the De natura rerum generalizes to the following conclusion: "a thing

should entirely lose its form and shape, and become nothing, and become again

something out of nothing, which has afterward become much nobler in its power

and virtue than it was originally."

One of the most

famous appearances of the Homunculus however is in the neo-Paracelsian

Chymieal Wedding of Christian Rosencreutz,

a baroque Bildungsroman published in 1616, written anonymously by Johann

Valentin Andreae. The hero of the romance, Rosencreutz, receives an anonymous invitation to the

mysterious wedding of a king and queen, delivered to him by a beautiful, winged

lady. After seeing a castle with invisible servants, a mysterious play

featuring lions, unicorns, and doves, and a roomful of wondrous self-moving

images, Rosencreutz finally meets the bride and

groom. At the end of a sumptuous dinner accompanied by an elaborate comedy, the

joyful couple, along with their royal retinue, are abruptly beheaded by a

"very cole-black tall man." (John Warwick

Montgomery, Cross and Crucible: Johann Valentin Andreae

(1586-1654), Phoenix of the Theologians, vol. 2,1973,414).

Their blood being carefully

collected, the bodies are then dissolved into another red liquor by Rosencreutz and a group of fellow alchemists. These laborants summarily congeal the fluid in a hollow globe,

whereon it becomes an egg. The alchemists then incubate the egg, which hatches

a savage black bird: the bird is fed the collected blood of the beheaded,

whereupon it molts and turns white and then iridescent. After a series of

further operations, the bird, now grown too gentle for its own good, is itself

deprived of its head and burnt to ashes.( J.W. Montgomery,Cross

and Crucible, 1971, vol. 2: p.440-456.)

This panoply of

processes is an obvious recitation of the traditional regimens or color-stages

that were supposed to lead to the agent of metallic transmutation, the philosophers'

stone. Indeed, the philosophers' stone was often described as the end result of

processes figuratively pictured in terms of copulating kings and queens who are

murdered and reborn. But in the end, the bodies of this bride and groom are

reassembled out of the ashes of the unfortunate bird by placing the moistened

mass into two little molds. Upon heating, there appear "two beautiful

bright and almost Transparent little Images ... a Male and a Female, each of

them only four inches long," which are then infused with life.

These are identified

in the margin as Homunculi duo. (Cross and Crucible,vol.

2:p.458.)

The reader, having

expected the end result to be the philosophers' stone, may be somewhat

surprised at this result. This at least was the reaction of the alchemists who

were employed at the court of the decapitated couple, for Rosencreutz

informs us that they imagined the process to have been carried out "for

the sake of Gold," adding that "to work in Gold... is indeed a piece

also of this art, but not the most Principal, most necessary, and best."

In short, according to the Chymical Wedding of

Christian Rosencreutz, the real goal of alchemy is

the artificial generation of human beings, and the manufacture of precious

metals only a sideline.

Andreae, the author of The Chymical

Wedding, was a well-known Lutheran theologian and the composer of the utopian Christianopolis. Perhaps it is unnecessary to say that for Andreae, the production of homunculi is largely an allegory

of spiritual regeneration with the aim of charming the reader rather than

teaching him to be a Frankenstein. (Montgomery, Cross and Crucible, vol. 2,

where the author demonstrates this point exhaustively in his commentary to the

text).

Andreae's reorientation of alchemy to the spiritual rebirth of

man has a history as long and devious as the operations described by Rosencreutz. Yet as we have observed, few seem to have

followed the path of Andreae in harnessing the

homunculus to the yoke of Christian soteriology. And indeed, the Paracelsian homunculus as pictured either in the De natura

rerum or in the De homunculis is an intractable

vehicle of salvation. Neither the "bodiless" product of human

artisanal mastery nor the obscene and tumorous growths of unbridled lust could

serve the ministrations of the regenerate soul.

Thus one can also say

The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosencreutz

is actually a part of the rejection-rather than an affirmation-of the Paracelsian homunculus, despite its obvious debt to the

literary tradition of Paracelsus indicating simple that there were several

different schools of so called 'Alchemy'.

For updates

click homepage here