|

Archaeology and Popular Culture |

In a 1993 book titled ” Peaks of Limuria” Richard Edlis who had

been Commissioner for the British Indian Ocean Territory, casually noted that

the islands under his stewardship "comprise all that remains above

sea-level of huge underwater mountains of volcanic origin which rear

dramatically from the ocean bed 10,000 feet or more below” (p.ix).

Similarly in Theosophical books, with which many Tamil place-makers were

undoubtedly familiar because of the visibility of these occultists in the

Madras Presidency, the name had come to be associated with a continent

inhabited by proto-human beings, and re-interpreted as the Kumarinâtu

of Tamil literature.

From the 1870’s, several European

ethnologists, especially those with a connection to British India, favored

India as the cradle of mankind. And even Ernst Haeckel in 1876 considered this

a possibility which came to the attention of Tamil's devotees. The principal

term used to designate the catastrophic and destructive agency of the ocean in

Tamil devotion's labors of loss initially however was katalkôl,

a word that has attained the same status among its place-makers that was

accorded to "the Deluge" or "the Flood" in the discourses

of the Judeo-Christian West well into the early decades of the nineteenth

century." Literally, "seizure by the sea," katalkôl

is frequently glossed in English as "flood," "ocean swell,"

and, significantly, as "deluge," or even "Deluge." All of

Tamil devotion's ocean fears and fantasies turn around this word, which is

used, over and again, to describe the actions of the "cruel sea" in

its labors of loss. It is because of katalkôl that

Tamil speakers irrevocably lost their patrimony as embodied in their

antediluvian words and works as these had been nurtured in their ancestral

homeland. Instead of sustaining Tamil homes and hearths today, their patrimony

lies consigned to a "watery grave" at the bottom of the Indian Ocean.

Then from the closing

years of the nineteenth century, similar lamentations about the

"countless" and "numerous" precious Tamil books and

"literary treasures" that met "a watery grave" are a

constant refrain of Tamil literature. These works were the creations, devotees

insist, of the 4,449 poets who had graced the first literary academy (cankam) in the antediluvial city of Tenmaturai,

and of the 3,700 bards of the second academy in the drowned city of Kapâtapuram. When these cities and their learned academies

were washed away by the ocean, they took with them-forever-these poets and

their works. While most do not venture to enumerate the books that are believed

to have been destroyed, settling instead for generic invocations of

"innumerable" and "many," some more daringly name names and

even discuss their contents. As early as 1887 C. W. Damodaram

Pillai (1832-1901) published many a forgotten Tamil literary work-wrote

poignantly of the lost texts of which he had heard when he was young and that

were no longer available in his time. These had been primarily lost to the

flood that had seized the second cadkam at Kapatapuram, but other forces, including gross negligence,

had been at work as well. And in 1903, drawing upon a Tamil commentarial

tradition that over the centuries had kept alive some memory of lost treatises,

a book titled the Suryanarayana Sastri recounted that works such as Mutunârai, Mutukuruku, Mâpuran am, and Putupurânam had

been seized by the ocean (p. 94-102).

Soon after, in 1917,

Abraham Pandither, in his massive history of Tamil

music, insisted that several of these lost works, such as Naratiyam,

Perunârai, and Perunkuruku,

had been the world's first treaties on music, all of which had disappeared into

the ocean along with several rare musical instruments like the

thousand-stringed lute. Thudisaikizhar Chidambaranar (1883-1954), a retired petty bureaucrat,

pointed to the loss of rare grammatical works, the first in the world.

There are many

reasons that make Lemuria's candidacy as the ancestral Tamil homeland so

attractive to Tamil devotion's place-making. It had been identified by

metropolitan scientists as a vast ancient continent and as the birthplace of

mankind: if Tamil speakers were the original inhabitants of Lemuria, this made

them, ipso facto, the most ancient peoples of the world and the ancestors of

all of humanity. As many insisted, with the sinking of the ancestral homeland,

Tamilians fanned out to the rest of the world, setding

and planting the seeds of civilization in the Indus Valley, Mesopotamia, Egypt,

China, the Americas, even Europe. Consequently, Lemuria allows Tamil labors of

loss to fashion a diaspora for Tamil and its speakers that was as widespread as

it was ancient, stretching back to the very beginning of time, in fact. It

allows modern Tamilians to assume the status of global peoples, if only

vicariously, in an age of global empires and the exercise of global power.

Furthermore, the

appropriation of Lemuria for the Tamil cause also enables the recasting of

modern Tamil speakers as descendants of an antediluvian people. This allows

Tamil writers to tap into all the symbolic potency-innocence, purity, and

singularity-associated with prelapsarian virtue and bliss. Lemuria thus

provides a context for summoning into existence a Tamil prelapsarium,

further deepening the antiquity of the language and its speakers, the first in

the subcontinent as well as in the entire inhabited world.

Even within the

community of Tamil devotees, which has been radically divided over the

meaning of Tamil and its relationship to the other languages, cultures, and

speakers of the subcontinent, most unite around the contention that Tamil is an

antediluvian language whose origins can be traced to the lost homeland of

Lemuria. Loss, therefore, is powerfully enabling in southern India, and is a

sentiment, therefore, that has to be continually fed and stoked. As Marilyn Ivy

has noted in another context, "the loss of nostalgia-that is, the loss of

the desire to long for what is lost because one has found the lost object-can

be more unwelcome than the original loss itself. Modernist nostalgia must

preserve the sense of absence and lack that motivates its desire.(Ivy,

Discourses of the Vanishing, University of Chicago Press, 1995.)

Tamil devotion's

complex and variegated ‘labors of loss’ cannot actually afford to find the lost

homeland, or to close the gap, to present the absent. To do so would mean the

end of its project, its own logic for existence. Thus the nostalgic is enamored

of distance, not of the referent itself. Nostalgia cannot be sustained without

loss. For the nostalgic to reach his or her goal of closing the gap between

resemblance and identity, lived experience would have to take place, an erasure

of the gap between sign and signified, an experience which would cancel out the

desire that is nostalgia's reason for existence Yearning for-and

mourning-the lost homeland becomes an end in itself, therefore, for a people

who imagine themselves in perpetual exile.

From the start, the

relationship of Lemuria to the lived homeland of Tamilnadu,

itself a small part of "India," is plagued by a strategic ambiguity

in Tamil place-making. Some suggest that all of what we know of as India today

had been part of Lemuria, spatially reiterating the claim that Dravidians (and

hence Tamilians) had been the original peoples of the subcontinent before they

had been driven south by "the Aryan invasion."170 Others are content

to include only peninsular India-that region of the subcontinent that colonial

ethnology proposed was populated by Dravidian speakers-in Lemuria. Still others

insist that only that part of India extending from Mount Venkatam

to Kanyakumari had ever been Part of Kumarinâtu, the

historic Tamilakam.

And yet the fact

remains, as I have already noted, that loyalty and attachment to the lived

homeland of Tamilnadu, itself a part of India, has

also to be generated, especially if Tamil's devotees want their fellow speakers

to rally together to protect and nurture their language and land-or what was

left of these after the ravages of time and after the onslaughts made on them

by rival languages and their patrons.

By the time the

speculations around Lemuria commenced in the later

half of the nineteenth century in Europe, the Flood as a global geological

event had become questionable in professional scientific circles, and from the

1840s credible geologists or natural historians were disinclined to draw upon

it to theorize the earth's deep past. Not surprisingly, the paleo-scientist

never invokes the universal Flood to account for submergence and subsidence in

his labors of loss around Lemuria. It is another measure of occultism's

contentious relationship with metropolitan science that leads its practitioners

to turn to diluvial events in their own catastrophic theories around Lemuria,

but even occult place making does not accord them the centrality that is given

them in Tamil devotion.

As an explanatory

device for global change as well, the Flood had fallen on bad times among

scientists in the metropole by the late nineteenth century. In contrast, it had

been, from the Renaissance into the Enlightenment, the central moment in the

drama of human history, to whose unveiling some of the best intellectual minds

of Europe had dedicated themselves. But the professionalization of the various

sciences in the nineteenth century had pushed the Deluge to the margins of

serious thought, where, dismissed as myth, legend, or fable, it languished as

yet another example of the magical and miracle-mongering mentality of the

pre-moderns.

The Flood, therefore,

as a geological or historical event, or even as an explanatory device, had

little credibility in disenchanted knowledge-practices, history included, by

the end of the nineteenth century. Yet, katalkôl

remained the principle engine that sustained the labors of loss that are so

important to Tamil devotion's place-making which commenced around this time.

For the Tamil place-maker, it is crucial to establish its historicity, as it is

to demonstrate that it had actually happened, at least once upon a time, if not

more than once. The very crux of the Tamil project around Lemuria is to

demonstrate that a Tamil antediluvium had really

existed, and more importantly, had mattered. But how can the place-maker go

about the business of reconstructing an ante-diluvial past in a

post-Enlightenment age that is so vigorously anti-diluvial? How can he use the

protocols and procedures of history to pursue an antediluvial project,

especially in the face of that discipline's very' hostility to such an enterprise?

What are some of the gains of doing so, aid what are some of the losses

incurred in allowing himself to be commandeered by history?

Given the conflicted

intimacy between Tamil devotion and the modern disciplinary formation of

history, it goes without saying that the degree to which Tamil place-makers are

historicist varies enormously, from the few who are completely in history to

some who are utterly outside it, with a majority falling somewhere in between.

The spread of historicist assumptions among modern Tamil intellectuals has yet

to be systematically documented by scholars, but for a suggestive essay that

links Brahmanical approaches to the past with (imperial) historicism, see V.

Geetha , Re-writing History in the Brahmin's Shadow: Caste and the

Modern, Historical Imagination. Journal of Arts and Ideas 25-26: 127-37.1993.

Pure fantasy

generates an imaginative and imaginary world through faithfully observing rules

of logic and inner consistency which, although they may differ from those

operating in our own world, must nevertheless be as true to themselves as their

parallel operations in the normal world. The world created by pure fantasy has

to necessarily be complete, self-consistent, and uncompromised by the demands

of prosaic realism.

Metropolitan

place-makers of Lemuria, with the exception of some American occultists and

fantasists, are not concerned with today's nation-states. Tamil labors of loss

are strikingly different in this regard as well, as its place-making repeatedly

questions the delineated borders of the emergent nation-state of

"India." The reasons for this are not far to seek, for from the

193os, more and more of Tamil's devotees came increasingly under the influence

of the Dravidian movement and its radical imagination of a nation outside the

spatial confines of India. Indeed, from the vantage point of an emergent Indian

nationalism, Tamil labors of loss are clearly extraterritorial, preoccupied as

they are with an ancestral homeland most of which falls outside the delineated

borders of India. So, the desire to imagine an alternative to India leads many

to spatially dissociate themselves from a territory that is deemed to be

contaminated by Aryanism, Brahmanism, Sanskrit, and Hindi, propelling them in

turn to locate their Utopia of perfection and plenitude elsewhere.

But because India is

also deemed to be originally and fundamentally Dravidian and Tamil, before the

Aryan hordes took it over, and because it is after all the ground for the

conduct of practical politics, Tamil place-makers cannot give up on it

entirely. Hence, spatially as well, Tamil labors of loss compromise, by

locating their imagined elsewhere partly within the borders of contemporary

India (whose own political contours changed dramatically over the course of the

twentieth century), and partly outside.

But a separatist

Dravidian nationalism is not the only force compelling Tamil devotion's extraterritorial

place-making. Working sometimes in opposition to Dravidianism's separatist

agenda prior to the 1940s, and then increasingly contrary to it from the 1950s,

is the pressure of Tamil nationalism, which found progressive accommodation

with Indian nationalism and with the latter's territorial imperatives. In fact,

for a decade and more from the late 1940’s Tamil nationalism's most important

territorial concern was to ensure that all those areas of the newly formed

Indian nation-state which were deemed to be Tamil-speaking should come under

the rule of a Tamil polity, and should become part of the newly formed Tamil

state of Madras. In these years, the anxiety is palpable that these regions

would be "lost" to Tamil-speakers in the process of accommodating the

territorial demands of their neighbors.

From the start, the

relationship of Lemuria to the lived homeland of Tamilnadu,

itself a small part of "India," is plagued by a strategic ambiguity

in Tamil place-making. Some suggest that all of what we know of as India today

had been part of Lemuria, spatially reiterating the claim that Dravidians (and

hence Tamilians) had been the original peoples of the subcontinent before they

had been driven south by "the Aryan invasion."170 Others are content

to include only peninsular India-that region of the subcontinent that colonial

ethnology proposed was populated by Dravidian speakers-in Lemuria. Still others

insist that only that part of India extending from Mount Venkatam

to Kanyakumari had ever been Part of Kumarinâtu, the

historic Tamilakam.

And yet the fact

remains, as I have already noted, that loyalty and attachment to the lived

homeland of Tamilnadu, itself a part of India, has

also to be generated, especially if Tamil's devotees want their fellow speakers

to rally together to protect and nurture their language and land-or what was

left of these after the ravages of time and after the onslaughts made on them

by rival languages and their patrons.

As the litterateur

(and Tamil devotee) P. Sundaram Pillai (1855-97) observed in 1895 on the very

eve of the commencement of the Tamil labors of loss around Lemuria, "We

have not, in fact, as yet, a single important date in the ancient history of

the Dravidians, ascertained and placed beyond the pale of controversy. It is no

wonder then that in the absence of such a sheet anchor, individual opinions

drift, at pleasure, from the 14th c. B.c. to the 14th

c. A.D.( Sundaram Pillai, Some Milestones in the History of Tamil Literature

Found In an Inquiry into the Age of Tiru Gnana Sambanda.

Madras, 1895,p.9-10.)

Nothing more clearly

demonstrates the Tamil place-maker's contention that his lost homeland really

did exist, if only in some long vanished prelapsarian past, than his effort to

introduce Kumarikkantam into the curriculum of

schools and colleges. Indeed, this also distinguishes Lemuria's presence in the

Tamil country from its appearance elsewhere, for nowhere else does Sclater's

lost continent become a part of pedagogical processes, and indirectly,

therefore, of the technologies of modern citizenship. Not surprisingly, there

are no attempts to fantasize outside the usual range of facts, as the

place-maker works to convince his young audience of the reality of Kumarikkantam, whose existence is presented until this day

as an indubitable "fact" of the (antediluvial) history and geography

of Tamilnadu, of India, and of the world. In these

textbook labors of loss, Kumarikkantam is too

important to be taken lightly-or fantastically.

From the early years

of the twentieth century history schoolbooks which circulated in Madras in

English and Tamil occasionally ponder over its status as a Dravidian homeland.

But none of these identify Lemuria as a singularly Tamil place, nor are they freighted

down with the sense of loss that so distinguishes the spatial preoccupations of

Tamil devotion. To encounter these, we have turn to textbooks meant for

Tamil-language instruction, in which, from the 1930’s, discussions of Lemuria

as a lost Tamil homeland begin to proliferate. Indeed, both in schools and

colleges in the colonial and postcolonial period, instruction in Tamil and its

literature has been the primary site for the institutionalization of Tamil

labors of loss around Lemuria. This is mostly because until 1967, when a Tamil

nationalist government was voted into power in the state, Tamil pedagogy,

beleaguered thought it might have been (especially in the early decades of the

twentieth century), was the principal institutional means through which Tamil

devotional ideas were disseminated outside a narrow circle of scholars. Thus

instructors in Tamil schools and colleges also frequently wrote textbooks

in which their labors of loss around the drowned Kumarinâtu

both found expression and were passed on to the young students.

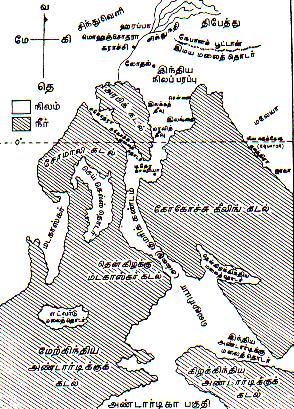

Thus a map of 1992,

published in Tamil, is named "The Lemuria Continent which was destroyed by

the ocean" by K. Thanikachalam in Tamilar Varalârum Ilafckai Itappeyer Ayvum [History of

Tamils and research on Sri Lanka as a place]. Madras: Saravana Patippakam.

While a map, in

English, of 1993 is called "Lemuria or The Lost Kumari-Continent or Navalam Island (David J.Manuel

Raj, History of Silamban Fencing: An Indian Martial Art. Madras) its allencompassing title revealing the three principal sources;European science, Tamil literature, and the

Sanskritic Purânas.

These Tamil

cartographies are forthright in their announcement of the principal

place-making claim of Tamil devotion: that there was an ancient Tamil land that

was lost in floods caused by the ocean's fury.

They are also

explicit in drawing attention to the fact that Lemuria was no impersonal or

homogenous paleo or occult place-world, but a Tamil homeland, by the naming

operations they perform on the land illustrated in their maps.

The map below titled

by R. Mathivanan, Marainta Lemüriak

Kantam [Vanished Lemuria Continent], in Tamil, it

shows the reconstructed Indian peninsula to the north, with a landbridge connecting to the large landmass of Lemuria in

the south, terminating in Antarctica. The shaded portions represent the oceans

surrounding Lemuria. From Ramachandran and Mathivanan, The Spring o/ the

Indus Civilizatio, Madras, 1991):

None have been so famous in popular archeology than

the myth of lost continents like Lemuria and Atlantis, so this is where our

case-study starts, click to enter:

|

|

||

For updates

click homepage here