Ambedkar (1891-1956),

leader of India's Untouchables, first encountered Buddhism through the Dravidian

Buddhist Society founded by that time President of the Theosophical Society and

author of “People from the other World,” Henry Olcott. During its inaugural

meeting in 1898 in Madras Olcott stated:

Buddhism will make

every man, woman and child among you free of all the oppression of caste; free

to work; free to look your fellowmen bravely in the face; free to rise to any

position within the reach of your talents, your intelligence and your perseverence; free to meet men, whether Asiatics,

Europeans or Americans on terms of friendly equality and competition; free to

follow out the religious path traced to the Lord Buddha without any priest

having the right to block your way; free to become teachers and models of

character to mankind. (Published in the Journal of the Maha Bodhi Society 7.4,

August 1898)

Although this hardly

can be said to count for Ambedkar, Colonel Olcott himself, was a lifelong

believer in an ‘astral plane’ and believed to be receiving messages from Madame

Blavatsky’s “Mahatmas.” Particularly two “Aryans” said to have survived the floods

of Atlantis Master Morya and his deputy, Master

Koot Hoomi, communicated with her regularly from

their alleged abode on top of the Himalayas by ‘materializing’ letters which

sometimes dropped from ceilings, but most often where delivered via a common spiritualist

trap door. And Olcott noted in his diaries that

"Our Buddhism was that of the Master-Adept Gautama Buddha, which was

identically the Wisdom Religion of the Aryan Upanishads, and the soul of all

the ancient world-faiths" (S. Prothero, The White Buddhist: The

Asian Odyssey of Henry Steel Olcott, 1996, p. 96.)

At a time when many

in the West were suffering a crisis of faith in the wake of the publication of

Darwin's Origin of Species (1859) and his later Descent of Man (1871), Madame H.P.Blavatsky began to attract a

circle of devotees in America, despite repeated scandals and accusations of

fraud. Spiritualism was very much in vogue, and 'forbidden' Tibet was coming to

be seen by the romantically minded as a spiritual paradise untainted by the

outside world. Colonel Olcott was an early admirer of Madame Blavatsky, and

when the Theosophical Society was formed in New York in November 1875 he became

its first President - with Madame Blavatsky as, appropriately enough, its

Corresponding Secretary. At first the Theosophical Society's aims were

ill-defined and the Masters' messages were taken up with the Great Mother and

Ancient Egyptian occultism, as explained by Serapis of the Luxor Brotherhood.

After moving to Bombay however, these soon gave way to the loftier goal of a

'Universal Brotherhood of Humanity'. Its creed drew upon the ancient truths of

the mahatmas that underpinned all the religions of the world - and pre-eminent

among these was Buddhism: “incomparably higher, more noble, more philosophical

and more scientific than the teaching of any other church or religion”.

(Charles Allen, The Buddha and the Sahibs, 2003, p.245.)

Case

Study 1: Seek Mason, Will Travel

In May 1880 the

unlikely couple - one bearded like an ancient prophet, ashen-grey of

complexion, austere in appearance and demeanour, the

other many times larger than life in both her figure and personality- moved on

to Ceylon. The Sinhalese population received them with open arms, for their

reputation as the first sahibs to have publicly expressed their high regard for

of the old religions reintroduced, from Thailand in 1753. They underscored this

by becoming, on 25 May, the first Russian and the first American to become lay

Buddhists. On landing at the quay at Bombay, Colonel Olcott had knelt down and kissed the ground; here in Ceylon he

abandoned his western attire for a dhoti, shawl and sandals.

The contrasting

attitudes of these two “chums”, as they called themselves, can be seen in their

very different responses to the Relic of the Tooth at Kandy when it was brought

from its golden case for their personal inspection: Madame Blavatsky blurted out

that it was as large as an alligator's tooth while Olcott, rather more

tactfully, expressed a belief that it obviously dated from one of the Buddha's

earlier incarnations. (Allen, 2003, p. 246.)

Olcott proceeded to

write a Buddhist Catechism, made up of questions and answers to be learned

by heart, and the role it played in the revival of Buddhism in Ceylon, and its

reform, was immense. But what is truly extraordinary about this document is

that even though it carried the imprimatur of the most respected Sinhalese monk

on the island, the Venerable Sri Hikkadowe Sumangala,

'High Priest of Sri Pada and the Western Province and Principal of the Vidyodaya Pirivena', and was

approved by him for use in Buddhist schools, the Buddhist Catechism reflected

Henry Olcott's rationalist views - views that in many instances ran contrary

to the Buddhist practices then prevailing on the island.

The Catechism asks:

'Did the Buddha hold with idol-worship?' Answer: 'He did not; he opposed it.

The worship of gods, demons, trees, etc. was condemned by the Buddha.' And the

summary of Buddhism that the American colonel set down in answer to the question

'What striking contrasts are there between Buddhism and what may be called

"religion"?' is a startlingly reformist, almost Presbyterian,

interpretation of Theravada Buddhism:

Answer: Among others,

these: It teaches the highest goodness without a creating God; a continuity of

life without adhering to the superstitious and selfish doctrine of an eternal,

metaphysical soul-substance that goes out of the body; a happiness without an

objective heaven; a method of salvation without a vicarious Saviour;

redemption by oneself as the Redeemer, 3fld without rites, prayers, penances,

priests or intercessory saints; and a summum bonum, i.e., Nirvana, attainable

in this life and in this world by leading a pure, unselfish life of wisdom and

of compassion to all beings.

One of those who

attended Colonel Olcott's first public lecture in Ceylon was Don David Hevavitherana, aged sixteen, son of Anglicised

Sinhalese parents, who had been educated at an Anglican church school in

Colombo.

His grandfather

became the Buddhist Theosophical Society's first President, and in 1884, at the

age of twenty, David himself was initiated as a member of the Society, and later took the name Anagarika Dharmapala.

In Olcott’s hands his

movement for Buddhist unity was anti-Christian in inspiration, Ambedkar in

contrast opposed the caste system. But this of course creates a contradiction,

for where Ambedkar imagined the Buddhist community to be a purely ethical community,

the Buddhist community itself is based on caste lines.

Following Olcott's

dead Annie Besant became the President of the Theosophical Society seen here at

the All-India Buddhist Literary Conference, Calcutta, December 27-29th 1928.

But we have to recall that Buddhist discourse responds and reacts

to other discourses: the Hindu Nationalist discourse promotes quite different

ideals and heroes.

In fact

the term "Hindu" is a Persian adaptation of the Sanskrit sindhu, referring to the region of the Indus River Valley.

In the late eighteenth century, British authors began using "Hindu"

to refer to the religions of the non-Muslim peoples of India.

The development in

ideas about the nature of religion had large implications for traditional forms

of authority. Many of the new leaders insisted that the distinction between

religious specialists Brahmins or monks-and lay people had to be abandoned or toned

down. Everybody should take part in the cultural heritage of the community.

Everybody should have access to the high scriptural tradition. Everybody should

essentially be a Brahmin or a monk. Religious identity in traditional

Brahminical religion was ascribed by birth and exclusive to certain members of

society, whereas religious membership in the order of monks, both Buddhist and

Jain, was achieved through initiation only.

There was a

difference of degree between the Hindu Vivekananda, the Buddhist Dharmapala,

and the Jain Vijaya Dharma Sfiri regarding their

internalization and espousal of new versus traditional world views. Dharmapala

was undoubtedly the most anglicized of these religious leaders and his break

with the Buddhist past was radical, although he would have denied this himself.

He was probably also the leader who made the most profound and lasting impact

on his own society.

Gombrich and Obeyesekere (1988) have

looked at the legacy of Dharmapala in the late twentieth century; their

conclusion is that Buddhism has been transformed by the new ideas of religious

authority and by the new and unprecedented religious roles of monks and lay

people.

Like Dharmapala, Vivekinanda was also thoroughly influenced by English

culture through his education, and his idea of the Indian past was conveyed

through European books on history and religion. It also marked as clear a

disjunction in the religious outlook of Jains as it did for Hindus and

Buddhists, and their arguments also were thoroughly influenced by the

historicist ideology of Western research and by the objectifying stance of the

British census.

In more general

terms, the new role of religion generated in the nineteenth century had

important implications for political life in South Asia in the twentieth

century. For instance, a large number of scholarly

works have shown how political monks played a pivotal part in the legitimation

of violent communal conflicts in both India and Sri Lanka during the last

decades. The Indian sub-continent is where nationalism and religion have found

their most complex field of interaction, I agree with P. Van der Veer that

religious discourse and practice must be treated as constitutive of changing

social identities rather than ideological smoke screens. To be more specific,

there is no doubt that religious nationalist ideology has been a cause of

political turmoil in South Asia.

In these movements

religion was a matter of choice and personal striving. Religious identity was

about belonging to a group of like-minded people whose religious duties and

privileges all accrued from their personal choices and abilities and not from

their social position. And Religion became a matter of choice.

Whether from Bengal, Gujarat, or Sri Lanka-all shared in a particular

perception of history. It was exported from Europe and gained currency among

the anglicized elites.

Comparative religion

provided much of the intellectual foundation for Dharmapala's thinking, as it

did for Vivekananda's, and the theosophist movement was an important channel

for the conveyance of these ideas to South Asia.

Max Mueller did much

to open the eyes of the British to the treasures of Indian literature and

religion. He was a key figure in the establishment of Sanskrit as a third

classical language in Britain and he argued that the Christian world needed to

study other religions and languages in order to

understand their own properly. India has something to teach us, was the essence

of his message to the British public. The ideas of race that flourished in the

same intellectual milieu became important elements in Dharmapala's nationalist

cosmology.

But a sense of

betrayal was often present in Dharmapala's personal relationships, vis-a-vis

his allies in the Theosophical Society, from whom he became alienated as the

Society associated itself more closely with an exclusivistic

Hindu nationalism.

Prothero (1995) was

the first to asserts that the Protestant Buddhism of Olcott was indeed a rather

a 'messy mix', which included important Western elements such as modernism,

metropolitan gentility, and academic orientalism.

Dharmapala described

in his diary for 9 Nov. 1897, and again on 12 April 1898, how “Theosophists

rose into prominence by borrowing Buddhist expressions. Their literature is

full of Buddhist terminology. Now they are kicking the ladder.”

In his diary of 12

January 1893, he wrote that Olcott pleaded guilty when he was confronted about

his “treacherous action” of writing against the Maha Bodhi Society. Discord did

in fact arise between Olcott and Dharmapala on a few occasions around the middle

of the 1890’s in connection with their work in the organization.

Moreover, it is clear that in the years before the turn of the

century, Olcott was increasingly torn between the cause of the Buddhists and

the Maha Bodhi Society, and the cause of Hindu nationalism and theosophy. It

will take a long time to efface the effects of Olcott's action, Dharmapala

continued in his diary, resolving to show understanding and love “though he has

proved treacherous to me”.

In a letter to one of

his companions, Mr Gunasekera, of 20 February 1926,

he related how the members of the Theosophical Society were against Buddhism

but still exploited the religion to advance their own cause. “Leadbeater and

Besant steal everything from Buddhism and palm it off as their own”, he said.

(Return to Righteousness, p.775)

In Calcutta Norendranath Sen became an important supporter of the

Buddhist. And through Neel Comul, Dharmapala also

became acquainted with the prominent Tagore family. Neel Comul's

wife had relatives among the Tagores

and his brother had married the sister of the great writer Rabindranath Tagore,

winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The Tagore family was

important in the formation of the Brahmo Samaj, the religious society founded

in 1828 by Rammohan Roy. Rabindranath's father, the conservative and

contemplative Debendranath Tagore, took over the leadership of the Brahmo Samdj from his father, Dwarkanath Tagore, in 1843. After

the social reformist Keshub Chandra Sen joined the

Brahmo Samaj a split occurred in the organization. Keshub Sen, the leader of the new Brahmo Samaj of India

from 1866, had a profound interest in Buddhism, and in the opinion of certain

scholars Sen was the main influence on Dharmapal to start the Maha Bodhi

Society. (David Kopf, The Brahmo Samaj, p. 252)

In Dharmapala's mind,

Buddhist Sri Lanka was a periphery in relation to Hindu India, and to Bengal in

particular. The Buddhists had a special historical relationship to Eastern

India because this was where the Buddha reached enlightenment and founded his

religion. It is in this perspective that Dharmapala's obsession with India can

be understood. Dharmapala's life-project was the remapping of the religious

geography of India. The Buddhists had a rightful place in that geography-both

the symbolic and the physical-which had been denied them in earlier phases of

the subcontinent's history, especially by the Muslims. In Dharmapala's mind the

identity of the Buddhist Sinhalese nation had to be defined in relationship to

the symbolic centre of their religion, which lay in

the heart of India, at Bodh Gaya.

The obsession with

ancient history and archaeology that took off among Indian religious leaders in

the nineteenth century was an expression of a completely new world view.

Dharmapala's attempt

to offer a new Buddhist identity consisted in negotiating symbolic territory in

the religious geography of India. As this symbolic geography translated into

real world geography as a piece of land owned by a Hindu Mahant, it entailed

real world negotiations in the law courts of Calcutta as well as untiring

polemic in the channels of public discourse, primarily the Indian Mirror.

Dharmapala's long struggle to gain control over Bodh Gaya therefore was a

struggle to define Buddhist identity for himself and for the Sinhalese nation

in relation to their symbolic centre in India.

But one of the most important traits of Dharmapala's Buddhism was the blurring

of the traditional roles of monk and layman.

Also the form of Hinduism developed by Vivekananda might

be called 'Protestant' in the limited sense that it stressed the universal

right to access to religious truths and a rejection of the traditional

authority of the priests. Of course, one may question the use of terms like

'Protestant Hinduism' and 'Protestant Buddhism'. The Protestant Buddhism of Sri

Lanka was certainly not a simple amalgamation of traditional Theravada Buddhism

and an ideal Weberian Protestantism.

The traditional

Indian type of religious identity, in fact was split into different identities

according to context. In Hinduism, the individual could have at least three

distinct types of religious identity: first, the social religious identity

defined by class and caste; secondly, the sectarian religious identity defined

by the family's affiliation to a devotional tradition centred

on a deity; and, thirdly, there was the option of a personal religion defined

by one's chosen guru.

Dharmapala's quest

for Bodh Gayd was not a pilgrimage in any traditional

Sinhalese Buddhist sense of a religious journey. His zealous attempts to

appropriate the Maha Bodhi temple made a claim about the place of Buddhism in

Indian history in the same way as the activities of Vijayendra Sfiri and Vijaya Dharma Sfiri

made claims about Jainism as a historical religious tradition.

Anagdrika Dharmapala spoke incessantly about the history of

Buddhism in relation to the history of other religions and civilizations, and

he often used the work of Western scholars to corroborate his arguments. Jain

leaders spoke of the history of Jainism, and scholars like Jacobi and Max

Mueller were favourite points of reference in their

discussions. Vivekananda read the history of Rome and Greece, of Egypt, of the

French Revolution, of modern Europe, of classical India, of the Mughals, and of

Buddhism. His views were often based on historical arguments, and, as T.

Raychaudhuri writes, his statements on history drew upon a fantastic range of

evidence from the records of many civilizations.

Although initially

influenced the small Buddhist conversion movement among Tamil Untouchables, the

Dravidian Buddhist Society, mentioned above Ambedkar (1891-1956), publicly

became a Buddhist shortly before his dead when he led half a million of his

followers into Buddhism. He gave many indications throughout his earlier life

that he intended to convert but held off, no doubt so as to

extract the maximum political concessions on behalf of the Untouchables, or

Dalits as they are called today. He was surely also aware of the symbolism of

converting in 1956, the two thousand five hundredth anniversary of the Buddha's

enlightenment.

Case

study 2: The Anti Aryan Myth

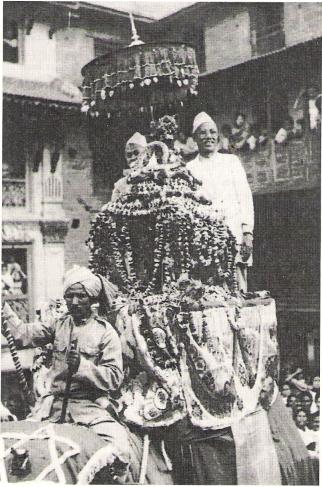

Ambedkar also

spoke about his coming conversion during a major conference organized by

the King of Nepal, in Katmandu. Below a newspaper clip showing the relics of

two disciples of the Buddha carried through Katmandu, during the conference

attended by delegates from 40 countries.

To date, nobody knows

where ‘Buddha’ was born, for example some claim it was in Bodh Gaya/India,

others that it was in Nepal and a third group of scholars claims he was

altogether born 100 years later from the above two presumptions. (See Robin Coningham, The archaeology of Buddhism. In Archaeology' and

World Religion, edited by T. Insol1, 2001).

Whatever it may be,

the official re-establishment of Budhism in Nepal

took some time for in 1926, the Rana government in Nepal still expelled six

Nyingma-lineage initiated Vajracharya monks on the

grounds, that one of them Mahapragya (fourth from

left), a Shrestha and therefore presumed to be a Hindu by birth, had converted

to Buddhism. Following is a 1927 newspaper clip, showing the five Newar monks

with their leader Tsering Norbu (third from left) originally from near Simla

India-- who had studied in the monastery of the Shakyashri

Lama--after their arrival in Bodh Gaya.

For updates

click homepage here