By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

Rationality and progress

As we have seen in our article about bias and why it occurs

across various judgment domains. People in all demographic groups display it,

and it is exhibited even by expert reasoners, the highly educated, and the

intelligent. Studies have shown a tendency toward the narrow search for evidence,

biased evaluation of evidence, biased memory of outcomes, and biased evidence

generation.

But there is also

some rationality to the myside bias, coming from game theory where Dan M.

Kahan calls it expressive

rationality: reasoning is driven by the goal of being valued by one’s peer

group rather than attaining the most accurate understanding of the world.

People express opinions that advertise where their heart lies. As far as the

fate of the expresser in a social milieu is concerned, flaunting those loyalty

badges is anything but irrational. Voicing a local heresy, such as rejecting

gun control in a Democratic social circle or advocating it in a Republican one,

can mark you as a traitor, a quisling, someone who doesn’t get it, and condemn

you to social death. Indeed, the best identity-signaling beliefs are often the

most outlandish ones. Any fair-weather friend can say the world is round, but

only a blood brother would say the world is flat, willingly incurring ridicule by

outsiders.

Unfortunately, what’s

rational for each of us seeking acceptance in a clique is not the rationale for

all of us in a democracy seeking the best understanding of the world. Our

problem is that we are trapped in what Hugo Mercier calls a Tragedy

of the Rationality Commons.1

The reality and mythology mindset.

For example, Mercier

notes that holders of weird beliefs often don’t have the courage of their

convictions. Though millions of people endorsed the rumor that Hillary Clinton

ran a child sex trafficking ring out of the basement of the Comet Ping Pong

pizzeria in Washington (the Pizzagate conspiracy

theory, a predecessor of QAnon), virtually none took

steps commensurate with such an atrocity, such as calling the police. The

righteous response of one of them was to leave a one-star review on Google.

(“The pizza was incredibly undercooked. Suspicious professionally dressed men

by the bar area that looked like regulars kept staring at my son and other kids

in the place.”) It’s hardly the response most of us would have if we thought

that children were being raped in the basement. At least Edgar Welch, the man

who burst into the pizzeria with his gun blazing in a heroic attempt to rescue

the children, took his beliefs seriously. The millions of others must have

believed the rumor in a very different sense of “believe.”

Mercier here points

out that impassioned believers in vast

conspiracies, like the 9/11 Truthers and the chemtrail theorists, publish

their manifestos and hold their meetings in the open despite their belief in a

brutally compelling plot by an autocratic regime to suppress brave

truth-tellers like them. It’s not the strategy you see from dissidents in

repressive regimes like North Korea or Saudi Arabia. Mercier, invoking a

distinction made by Sperber, proposes that conspiracy theories and other weird

beliefs are reflective, the result of conscious cogitation and theorizing, rather

than intuitive, the convictions we feel in our bones. It’s a powerful

distinction, though we draw it a bit differently, closer to the contrast that

the social psychologist Robert Abelson.

People divide their

worlds into two zones. One consists of the physical objects around them, the

other people they deal with, the memory of their interactions, and the rules

and norms that regulate their lives. People have mostly accurate beliefs about

this zone, and they reason within it. They believe there’s a real-world and

that ideas about it are true or false. They have no choice: that’s the only way

to keep gas in the car, money in the bank, and the kids clothed and fed.

The other zone is the

world beyond immediate experience: the distant past, the unknowable future,

faraway peoples and places, small corridors of power, the microscopic, the

cosmic, the counterfactual, the metaphysical. People may entertain notions

about what happens in these zones, but they have no way of finding out, and

anyway, it makes no discernible difference to their lives. Beliefs in these

zones are narratives, which may be entertaining or inspiring, or morally

edifying. Whether they are literally “true” or “false” is the wrong question.

The function of these beliefs is to construct a social reality that binds the

tribe or sect and gives it a moral purpose. Call it the mythology

mindset.

Bertrand Russell

famously said, “It is

undesirable to believe a proposition when there is no ground whatsoever for

supposing it is true.” The key to understanding rampant irrationality is

recognizing that Russell’s statement is not a truism but a revolutionary

manifesto. There were no grounds for supposing that propositions about remote

worlds were true for most human history and prehistory. But beliefs about them

could be empowering or inspirational, and that made them desirable

enough.

Russell’s maxim is

the luxury of a technologically advanced society with science, history,

journalism, and their infrastructure of truth-seeking, including archival

records, digital datasets, high-tech instruments, and communities of editing,

fact-checking, and peer review. We children of the Enlightenment embrace

universal realism: we hold that all our beliefs should fall within the reality

mindset. We care about whether our creation story, our founding legends, our

theories of invisible nutrients and germs and forces, our conceptions of the

powerful, are true or false. We have the tools to get answers to these

questions, or at least to assign them warranted degrees of credence. We have a

technocratic state that should put these beliefs into practice.

It is not the natural

human way of believing. The human mind is adapted to understanding remote

spheres of existence through a mythology mindset, it’s not because we descended

from Pleistocene hunter-gatherers specifically, but because we lacked the Enlightenment ideal of universal realism.

Submitting one’s beliefs to the trials of reason and evidence is an unnatural

skill, like literacy and numeracy, and must be instilled and cultivated.

And for all the

conquests of the reality mindset, the mythology mindset still occupies swaths

of territory in the landscape of mainstream belief. The obvious example is

religion. More than two billion people believe that if one doesn’t accept Jesus

as one’s savior, one will be damned to eternal torment in hell. Fortunately,

they don’t take the next logical step and try to convert people to Christianity

at swordpoint for their good or torture heretics who

might lure others into damnation. Yet in past centuries, when Christian belief

fell into the reality zone, many Crusaders, Inquisitors, conquistadors, and

soldiers in the Wars of Religion treated their beliefs

as literally true. For that matter, though many people profess to believe

in an afterlife, they seem to be in no hurry to leave this vale of tears for

eternal bliss in paradise.

Thankfully, Western

religious belief is safely parked in the mythology zone, where many people are

protective of its sovereignty. In the mid-aughts, the “New Atheists,” Sam

Harris, Daniel Dennett, Christopher Hitchens, and Richard Dawkins, became

targets of vituperation not just from Bible-thumping evangelists but also

from mainstream intellectuals. They did not counter that God exists. They

implied that it is inappropriate, uncouth, or just not done to consider God’s

existence a matter of truth or falsity. Belief in God is an idea that falls

outside the sphere of testable reality.

Another zone of

mainstream unreality is the national myth. Wich as we

argued before, whereas the nationalist system was in full effect in Europe

throughout most of the nineteenth century, its’

success in other parts of the world came along at a later point. Whereby

today, most countries enshrine a founding narrative as part of their collective

consciousness. These were epics of heroes and gods, like the Iliad, the Aeneid,

Arthurian legends, and Wagnerian operas. More recently, they have been wars of

independence or anticolonial struggles. Common themes include:

The nation’s ancient

essence is defined by a language, culture, and homeland.

An extended slumber

and glorious awakening.

A long history of

victimization and oppression.

A generation of superhuman

liberators and founders.

Guardians of the

mythical heritage don’t feel a need to get to the bottom of what transpired.

They may resent the historians who place it in the reality zone and unearth its

shallow history, constructed identity, reciprocal provocations with the

neighbors, and founding fathers’ feet of clay. Still, another zone of

not-quite-true-not-quite-false belief is historical fiction and, as we have

shown in the case of Irish and Scottish Nationalists, fictionalized history.

On the other hand,

when the events come too close to the present, or the fictionalization rewrites

important facts, historians can sound an alarm, as when Oliver Stone brought an

assassination conspiracy theory to life in the 1991 movie JFK. In 2020, others objected

to the television series The Crown, a dramatized history of Queen Elizabeth

and her family, which took liberties with many depicted events. Most critics

and viewers had no problem with the sumptuously filmed falsehoods. Netflix

refused to post a warning that some of the scenes were fictitious (though they

did post a trigger warning

about bulimia).

Offering reasons why

rationality matters is a bit like blowing into your sails or lifting yourself

by your bootstraps: it cannot work unless you first accept the ground rule that

rationality is the way to decide what matters.

We all do accept the

primacy of reason, at least tacitly, as soon as we discuss this issue, or any

issue, rather than coercing assent by force. It’s now time to raise the stakes

and ask whether the conscious application of reason improves our lives and makes

the world a better place. Given that reality is governed by logic and physical

law, it ought to be. Do people suffer harm from their fallacies, and would

their lives go better if they recognized and thought their way out of them? Or

is a gut feeling a better guide to life decisions than cogitation, with its

risk of overthinking and rationalization?

One can ask the same

questions about the welfare of the world. Is progress a story of

problem-solving, driven by philosophers who diagnose ills and scientists and

policymakers who find remedies? Or is progression a story of struggle, with the

downtrodden rising up and overcoming their oppressors?

We detailed why to

distrust false dichotomies and

single-cause explanations, so the answers to these questions will not be

just one or the other. Are the fallacies and illusions we described above just

wrong solutions to complex math problems? Or can poor reasoning lead to

actual harm, implying that critical thinking could protect people from their

own worst cognitive instincts?

We discount the

future myopically, but it always arrives, minus the large rewards we sacrificed

for the quick high. We assess danger by availability and avoid safe planes for

dangerous cars we drive while texting. We misunderstand regression as the mean and

so pursue illusory explanations for successes and failures.

In dealing with

money, our blind spot for exponential growth makes us save too little for

retirement and borrow too much with our credit cards. Our failure to discount

post hoc sharpshooting, and our misplaced trust in experts over actuarial

formulas, lead us to invest inexpensively managed funds that underperform

simple indexes. Our difficulty with expected utility tempts us with insurance

and gambles that leave us worse off in the long run.

Our difficulty with

logic can lead us to overinterpret a positive test for the uncommon disease in

dealing with our health. We can be persuaded or dissuaded from surgery

depending on the words in which the risks are framed. Our intuitions about

essences lead us to reject lifesaving vaccines and embrace dangerous quackery.

Illusory correlations and confusion of causation lead us to accept worthless

diagnoses and treatments from physicians and psychotherapists. A failure to

weigh risks and rewards lulls us into taking foolish risks with our safety and

happiness.

In the legal arena,

probability blindness can lure judges and juries into miscarriages of justice

by vivid conjectures and post hoc probabilities.

A failure to appreciate the tradeoff between hits and false alarms leads them

to punish many innocents for convicting a few more of the guilty.

In many of these

cases, the professionals are as vulnerable to folly as their patients and

clients, showing that intelligence and expertise provide no immunity to

cognitive infections. The classic illusions have been demonstrated in medical

personnel, lawyers, investors, brokers, sportswriters, economists, and

meteorologists, all dealing with figures in their specialties.

These are some of the

reasons to believe that failures of rationality have consequences in the world.

Can the damage be quantified? The critical-thinking activist Tim Farley tried

to do that on his website and Twitter feed named after the frequently asked

question “What’s the

Harm?” Farley had no way to answer it precisely, of course. Still, he tried

to awaken people to the enormity of the damage wreaked by failures of critical

thinking by listing every authenticated case he could find. From 1970 through

2009, but mainly in the last decade in that range, he documented 368,379 people

killed, more than 300,000 injured, and $2.8 billion in economic damages from

blunders in critical thinking. They include people killing themselves or their

children by rejecting conventional medical treatments or using herbal,

homeopathic, holistic, and other quack cures; mass suicides by members of

apocalyptic cults; murders of witches, sorcerers, and the people they cursed;

guileless victims bilked out of their savings by psychics, astrologers, and other

charlatans; scofflaws and vigilantes arrested for acting on conspiratorial

delusions; and economic panics from superstitions and false rumors.

Yet as Farley would

be the first to note, not even thousands of anecdotes can prove that

surrendering to irrational biases leads to more harm than overcoming them. At

the very least, we need a comparison group, namely the effects of

reason-informed institutions such as medicine, science, and democratic

government.

We do have one study

of the effects of rational decision-making on life outcomes. The psychologists Wändi Bruine de Bruin, Andrew

Parker, and Baruch Fischhoff developed a measure of competence in reasoning and

decision making by collecting tests for some of the fallacies and biases that we discussed.

Not surprisingly,

people’s skill in avoiding fallacies was correlated with their intelligence,

though only partly. It was also correlated with their decision-making style,

the degree to which they said they approached problems reflectively and

constructively rather than impulsively and fatalistically. The trio developed a

kind of scale to measure life outcomes, a measure of people’s susceptibility to

mishaps large and small.

They

found that people’s reasoning skills did indeed predict their life

outcomes: the fewer fallacies in reasoning, the fewer debacles in life.

Correlation is not

causation. Reasoning competence is correlated with raw intelligence, and we

know that higher intelligence protects people from bad outcomes in life, such

as illness. But intelligence is not the same as rationality since being good at

computing means that a person will add the right things. Rationality also

requires reflectiveness, open-mindedness, and mastery of cognitive tools like

formal logic and mathematical probability. Bruine de

Bruin and her colleagues did the multiple

regression analyses and found that better reasoners suffered fewer bad

outcomes even when they held intelligence constant.

Socioeconomic status,

too, confounds one’s fortunes in life. Poverty is an obstacle course,

confronting people with the risks of unemployment, substance abuse, and other

hardships. But here, too, the regression analyses showed that better reasoners

had better life outcomes, holding socioeconomic status constant.

Rationality and progress

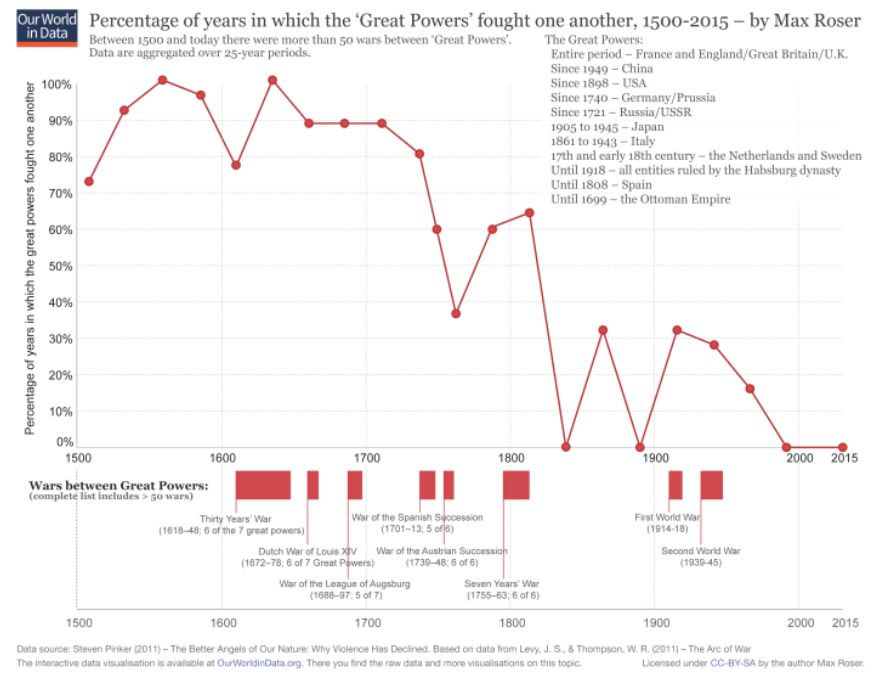

Though the

availability bias hides it from us, human progress is an empirical fact. When

we look beyond the headlines to the trend lines, we find that humanity overall

is healthier, wealthier, longer-lived, better fed, better educated, and safer

from war, murder, and accidents than in decades and centuries past. Beginning

in the second half of the nineteenth century, life expectancy at birth rose

and, according to available statistics, has continued

to do so.

The world has not yet

put an end to war, as the folk singers of the 1960s dreamed, but it has

dramatically reduced their

number and lethality:

More vigorous efforts

are needed to reduce the global homicide rate, but also that has been falling slowly.

In the end, it is

good to care about people’s virtue when considering them as friends, but not

when considering the ideas they voice. Ideas are true or false, consistent or

contradictory, conducive to human welfare or not, regardless of who thinks

them. The equality of sentient beings, grounded in the logical irrelevance of

the distinction between “me” and “you,” is an idea that people through the ages

rediscover, pass along, and extend to new living things, expanding the circle

of sympathy like dark moral energy.

Sound arguments,

enforcing consistency of our practices with our principles and with the goal of

human flourishing, cannot improve the world itself. But they have guided and

should guide movements for change. They make the difference between moral force

and brute force, between marches for justice and lynch mobs, between human

progress and breaking things. And it will be sound arguments, both to reveal

moral blights and discover feasible remedies, that we will need to ensure that

moral progress will continue, that the abominable practices of today will

become as incredible to our descendants as heretic burnings and slave auctions

are to us.

The power of

rationality to guide moral progress is a piece with its capacity to guide

material progress and wise choices in our lives. We can eke out of a pitiless

cosmos and be good to others by grasping equitable principles that transcend

our parochial experience despite our flawed nature. We are a species endowed

with an elementary faculty of reason, which has discovered formulas and

institutions that magnify its scope. They awaken us to ideas and expose us to

realities that confound our intuitions but are valid for all that.

1. Hugo Mercier,

Not born yesterday: The science of who we trust and what we believe. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020, pp. 191–97.

For updates click homepage here