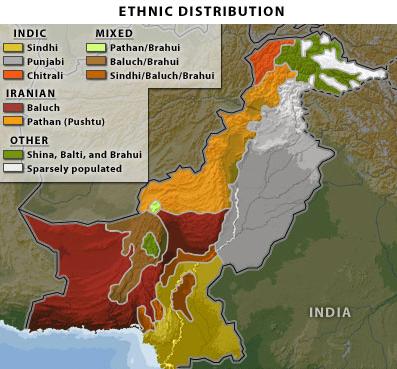

While Pakistan has

relatively definable boundaries, it lacks the ethnic and social cohesion of a

strong nation-state. Three of the four major Pakistani ethnic groups, Punjabis,

Pashtuns and Baluch, are not entirely in Pakistan. India has an entire state

called Punjab, 42 percent of Afghanistan is Pashtun, and Iran has a significant

Baluch minority in its Sistan-Baluchistan province.

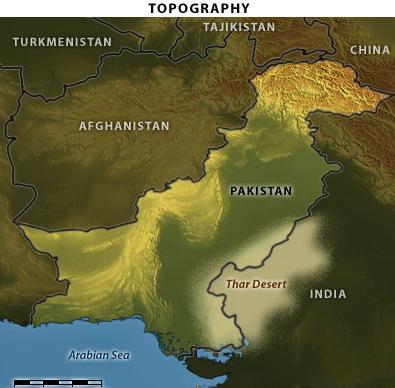

Thus, the challenge

to Pakistan’s survival is twofold. First, the only route of expansion that

makes any sense is along the fertile Indus River Valley, but that takes

Pakistan into India’s front yard. The converse is also true: India’s logical

route of expansion through Punjab takes it directly into Pakistan’s core.

Second, Pakistan faces an insurmountable internal problem. In its efforts to

secure buffers, it is forced to include groups that, because of mountainous

terrain, are impossible to assimilate.

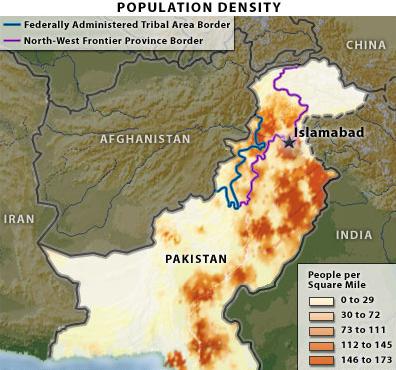

The first challenge

is one that has received little media attention of late but remains the issue

for long-term Pakistani survival. The second challenge is the core of

Pakistan’s “current” problems: The central government in Islamabad simply

cannot assert its writ into the outer regions, particularly in the Pashtun

northwest, as well as it can at its core.

The Indus core could

be ruled by a democracy, it is geographically, economically and culturally

cohesive, but Pakistan as a whole cannot be democratically ruled from the Indus

core and remain a stable nation-state. The only type of government that can realistically

attempt to subjugate the minorities in the outer regions, who make up more than

40 percent of Pakistan’s population, is a harsh one (i.e., a military

government). It is no wonder, then, that the parliamentary system Pakistan

inherited from its days of British rule broke down within four years of

independence, which was gained in 1947 when Great Britain split British India

into Muslim-majority Pakistan and Hindu-majority India. After the 1948 death of

Pakistan’s founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, British-trained civilian bureaucrats

ran the country with the help of the army until 1958, when the army booted out

the bureaucrats and took over. Since then there have been four military coups,

and the army has ruled the country for 33 of its 61 years in existence.

While Pakistani

politics is rarely if ever discussed in this context, the country’s military

leadership implicitly understands the dilemma of holding onto the buffer

regions to the north and west. Long before military leader Gen. Mohammed

Zia-ul-Haq (1977-1988) began Islamizing the state, the army’s central command

sought to counter the secular, left-wing, ethno-nationalist tendencies of the

minority provinces by promoting an Islamic identity, particularly in the

Pashtun belt. At first, the idea was to strengthen the religious underpinning

of the republic in order to meld the outlands more closely with the core.

Later, in the wake of the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan

(1978-1989), Pakistan’s army began using radical Islamism as an arm of foreign

policy. Islamist militant groups, trained or otherwise aided by the government,

were formed to push Islamabad’s influence into both Afghanistan and

Indian-administered Kashmir.

As Pakistan would

eventually realize, however, the strategy of promoting an Islamic identity to

maintain domestic cohesion while using radical Islamism as an instrument of

foreign policy would do far more harm than good.

Pakistan’s

Islamization policy culminated in the 1980s, when Pakistani, U.S. and Saudi

intelligence services collaborated to drive Soviet troops out of Afghanistan by

arming, funding and training mostly Pashtun Afghan fighters. When the Soviets

withdrew in 1989, Pakistan was eager to forge a post-communist Islamist

republic in Afghanistan, one that would be loyal to Islamabad and hostile to

New Delhi. To that end, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency

threw most of its support behind Islamist rebel leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar of Hizb i-Islami.

But things did not

quite go as planned. When the Marxist regime in Kabul finally fell in 1992, a

major intra-Islamist power struggle ensued, and Hekmatyar lost much of his

influence. Amid the chaos, a small group of madrassah teachers and students who

had fought against the Soviets rose above the factions and consolidated control

over Afghanistan’s Kandahar region in 1994. The ISI became so impressed by this

Taliban movement that it dropped Hekmatyar and joined with the Saudis in

ensuring that the Taliban would emerge as the vanguard of the Pashtuns and the

rulers of Kabul.

The ISI was not the

only one competing for the Taliban’s attention. A small group of Arabs led by

Osama bin Laden reopened shop in Afghanistan in 1996, looking to use a

Taliban-run government in Afghanistan as a launchpad for reviving the

caliphate. Ultimately, this would involve overthrowing all secular governments

in the Muslim world (including the one sitting in Islamabad.) The secular,

military-run government in Pakistan, on the other hand, was looking to use its

influence on the Taliban government to wrest control of Kashmir from India.

While Pakistan’s ISI occasionally collaborated with al Qaeda in Afghanistan on

matters of convenience, its goals were still ultimately incompatible with those

of bin Laden. Pakistan was growing weary of al Qaeda’s presence on its western

border, but soon became preoccupied with an opportunity developing to the east.

The Pakistani

military saw an indigenous Muslim uprising in Indian-administered Kashmir in

1989 as a way to revive its claims over Muslim-majority Kashmir. It did not

take long before the military began developing small guerrilla armies of

Kashmiri Islamist irregulars for operations against India. When he was a

two-star general and the army’s director-general of military operations, former

Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf played a leading role in refining the

plan, which became fully operational in the 1999 Kargil War. Pakistan’s war

strategy was to infiltrate Kashmiri Islamist guerrillas across the Line of

Control (LoC) while Pakistani forces occupied high-altitude positions on Kargil

Mountain. When India became aware of the infiltration, it sought to dislodge

the guerrillas, at which point Pakistani artillery opened up on Indian troops

positioned at lower-altitude base camps. While the Pakistani plan was initially

successful, Indian forces soon regained the upper hand and U.S. pressure helped

force a Pakistani retreat.

But the defeat at

Kargil did not stop Pakistan from pursuing its Islamist militant proxy project

in Kashmir. Groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Hizb-ul-Mujahideen, Harkat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami, Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) and Al Badr

spread their offices and training camps throughout Pakistani-occupied Kashmir

under the guidance of the ISI. Whenever Islamabad felt compelled to turn up the

heat on New Delhi, these militants would carry out operations against Indian

targets, mostly in the Kashmir region.

India, meanwhile,

would return the pressure on Islamabad by supporting Baluchi rebels in western

Pakistan and providing covert support to the ethnic Tajik-dominated Northern

Alliance, the Taliban’s main rival in Afghanistan. While Pakistan grew more and

more distracted by supporting its Islamist proxies in Kashmir, the Taliban grew

more attached to al Qaeda, which provided fighters to help the Taliban against

the Northern Alliance as well as funding when the Taliban were crippled by an

international embargo. As a result, al Qaeda extended its influence over the

Taliban government, which gave al Qaeda free rein to plan and stage the

deadliest terrorist attack to date against the West.

The Post 9/11 Environment

On Sept. 11, 2001,

when the World Trade Center towers and the Pentagon were attacked, the United

States put Pakistan in a chokehold: Cooperate immediately in toppling the

Taliban regime, which Pakistan had nurtured for years, or face destruction.

Musharraf tried to buy some time by reaching out to Taliban leaders like Mullah

Omar to give up bin Laden, but the Taliban chief refused, making it clear that

Pakistan had lost against al Qaeda in the battle for influence over the

Taliban.

Just a few months

after the 9/11 attacks, in December 2001, Kashmiri Islamist militants launched

a major attack on the Indian parliament in New Delhi. Still reeling from the

pressure it was receiving from the United States, Islamabad was now faced with

the wrath of India. Both dealing with an Islamist militant threat, New Delhi

and Washington tag-teamed Islamabad and tried to get it to cut its losses and

dismantle its Islamist militant proxies.

To fend off some of

the pressure, the Musharraf government banned LeT and

JeM, two key Kashmiri Islamist groups fostered by the ISI and with close ties

to al Qaeda. India was unsatisfied with the ban, which was mostly for show, and

proceeded to mass a large military force along the LoC in Kashmir. The

Pakistanis responded with their own deployment, and the two countries stood at

the brink of nuclear war. U.S. intervention allowed India and Pakistan to step

back from the precipice. In the process, Washington extracted concessions from

Islamabad on the counterterrorism front, and official Pakistani support for the

Afghan Taliban withered within days.

The Devolution of the Secret Service (ISI)

The post 9/11

shake-up ignited a major crisis in the Pakistani military establishment. On one

hand, the military was under extreme pressure to stamp out the jihadists along

its western border. On the other hand, the military was fearful of U.S. and

Indian interests aligning against Pakistan. Islamabad’s primary means of

keeping Washington as an ally was its connection to the jihadist insurgency in

Afghanistan. So Islamabad played a double game, offering piecemeal cooperation

to the United States while maintaining ties with its Islamist militant proxies

in Afghanistan.

But the ISI’s grip

over these proxies was already loosening. In the run-up to 9/11, al Qaeda not

only had close ties to the Taliban regime, but also had reached out to ISI

handlers whose job it was to maintain links with the array of Islamist militant

proxies supported by Islamabad. Many of the intelligence operatives who had

embraced the Islamist ideology were working to sabotage Islamabad’s new

alliance with Washington, which threatened to destroy the Islamist militant

universe they had created. While the ISI leadership was busy trying to adjust

to the post-9/11 operating environment, others within the middle and junior

ranks of the agency started to engage in activities not necessarily sanctioned

by their leadership.

As the influence of

the Pakistani state declined, al Qaeda’s influence rose. By the end of 2003,

Musharraf had become the target of at least three al Qaeda assassination

attempts. In the spring of 2004, Musharraf, again under pressure from the

United States, was forced to send troops into the tribal badlands for the first

time in the history of the country. Pakistani military operations to root out

foreign fighters ended up killing thousands in the Pashtun areas, creating

massive resentment against the central government.

In October 2006, when

a deadly U.S. Predator strike hit a madrassah in Bajaur agency, killing 82

people, the stage was set for a jihadist insurgency to move into Pakistan

proper. The Pakistani Taliban linked up with al Qaeda to carry out scores of

suicide attacks, most against military targets and all aiming to break

Islamabad’s resolve to combat the insurgency. A major political debacle threw

Islamabad off course in March 2007, when Musharraf’s government was hit by a

pro-democracy movement after he dismissed the country’s chief justice. Four

months later, a raid on Islamabad’s Red Mosque, which Islamist militants had

occupied, threw more fuel onto the insurgent fires, igniting suicide attacks in

major Pakistani cities like Karachi and Islamabad, while the writ of the state

continued to erode in the NWFP and FATA.

Musharraf was forced to

step down as army chief in November 2007 and as president in August 2008,

ushering in an incoherent civilian government. In December 2007, the world got

a good glimpse of just how dangerous the murky ISI-jihadist nexus had become

when the political chaos in Islamabad was exploited with a bold suicide attack

that killed Pakistani opposition leader Benazir Bhutto. Historically, the

Pakistani military had been relied on to step in and restore order in such a

crisis, but the military itself was coming undone as the split widened between

those willing and those unwilling to work with the jihadists. Now, in the final

days of 2008, the jihadist insurgency is raging on both sides of the

Afghan-Pakistani border, with the country’s only guarantor against collapse,

the military, in disarray.

India has watched

warily as Pakistan’s jihadist problems have intensified over the past several

years. Of utmost concern to New Delhi have been the scores of Kashmiri Islamist

militants who had been operating on the ISI’s payroll, and who had a score to settle

with India. As Pakistan became more and more distracted with battling jihadists

within its own borders, the Kashmiri Islamist militant groups began loosening

their bonds with the Pakistani state. Groups such as LeT

and JeM, who had been banned and forced underground following the 2001 Indian

parliament attack, started spreading their tentacles into major Indian cities.

These groups retained links to the ISI, but the Pakistani military had bigger

issues to deal with and needed to distance itself from the Kashmiri Islamists.

If these groups were to continue to carry out operations, Pakistan needed some

plausible deniability.

Over the past several

years, Kashmiri Islamist militant groups have carried out sporadic attacks

throughout India. The attacks have involved commercial-grade explosives rather

than the military-grade RDX that is traditionally used in Pakistani-sponsored attacks,

another sign that the groups are distancing themselves from Pakistan. The

attacks, mostly against crowded transportation hubs, religious sites (both

Hindu and Muslim) and marketplaces, were designed to ignite riots between

Hindus and Muslims that would compel the Indian government to crack down and

revive the Kashmir cause.

However, India’s

Hindu nationalist and largely moderate Muslim communities failed to take the

bait. It was only a matter of time before these militant groups began seeking

out more strategic targets that would affect India’s economic lifelines and

ignite a crisis between India and Pakistan. As these groups became increasingly

autonomous, they also started linking up with members of al Qaeda’s

transnational jihadist movement, who had a keen interest in stirring up

conflict between India and Pakistan to divert the attention of Pakistani forces

to the east.

By November 2008,

this confluence of forces, Pakistan’s raging jihadist insurgency, the

devolution of the ISI and the increasing autonomy of the Kashmiri groups,

created the conditions for one of the largest militant attacks in history to

hit Mumbai, highlighting the extent to which Pakistan has lost control over its

Islamist militant proxy project.

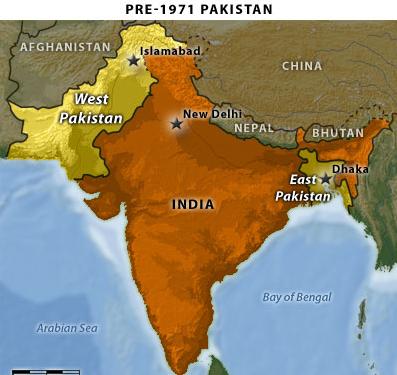

The India-Pakistan Rivalry

The very real

possibility that India and Pakistan could soon engage in what would be their

fifth war after nearly five years of peace talks is a testament to the

endurance of their 60-year rivalry. The seeds of animosity were sown during the

bloody 1948 partition, in which Pakistan and India split from each other along

a Hindu/Muslim divide. The sorest point of contention in this subcontinental

divorce centered around the Muslim-majority region of Kashmir, whose princely

Hindu ruler at the time of the partition decided to join India, leading the

countries to war a little more than two months after their independence. That

war ended with India retaining two-thirds of Kashmir and Pakistan gaining

one-third of the Himalayan territory, with the two sides separated by a Line of

Control (LoC). The two rivals fought two more full-scale wars, one in 1965 in

Kashmir, and another in 1971 that culminated in the secession of East Pakistan

(now Bangladesh.)

Shortly after India

fought an indecisive war with China in 1962, the Indian government embarked on

a nuclear mission, conducting its first test in 1974. By then playing catch-up,

the Pakistanis launched their own nuclear program soon after the 1971 war. The

result was a full-blown nuclear arms race, with the South Asian rivals devoting

a great deal of resources to developing and testing short-range and

intermediate missiles. In 1998, Pakistan and India conducted a series of

nuclear tests that earned international condemnation and officially nuclearized

the subcontinent.

Once the nuclear

issue was added to the equation, Pakistan became bolder in its use of Islamist

militant proxies to keep India locked down. Such groups became Pakistan’s

primary tool in its military confrontation, as the presence of nuclear weapons,

from Pakistan’s point of view, significantly decreased the possibility of

full-scale conventional war. Pakistan’s ISI also had a hand in a Sikh rebel

movement in India in the 1980s, and it continues to use Bangladesh as a

launchpad for backing a number of separatist movements in India’s restive

northeast. In return, India would back Baluchi rebels in Pakistan’s western

Baluchistan province and extend covert support to the anti-Taliban Northern

Alliance in Afghanistan throughout the 1990s.

Indian movements in

Afghanistan, a country Pakistan considers a key buffer state for extending its

strategic depth and guarding against invasions from the west, will always keep

Islamabad on edge. When Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan in 1979, Pakistan was

trapped in an Indian-Soviet vise, making it all the more imperative for the

ISI’s support of the Afghan mujahideen to succeed in driving the Soviets back

east.

Pakistan spent most

of the 1990s trying to consolidate its influence in Kabul to protect its

western frontier. By 2001, however, Pakistan once again started to feel the

walls closing in. The 9/11 attacks, followed shortly thereafter by a Kashmiri

Islamist militant attack on the Indian parliament, brought the United States

and India into a tacit alliance against Pakistan. Both wanted the same thing,

an end to Islamist militancy, and this time there was no Cold War paradigm to

prevent New Delhi and Washington from having a broader, more strategic

relationship.

This was Pakistan’s

worst nightmare. The military knew Washington’s post-9/11 alliance with

Islamabad was short-term and tactical in nature in order to facilitate the U.S.

war in Afghanistan. They also knew that the United States was seeking a

long-term strategic alliance with the Indians to sustain pressure on Pakistan,

hedge against Russia and China and protect supply lines running from the

oil-rich Persian Gulf. In essence, the United States felt temporarily trapped

in a short-term relationship with Pakistan while in the long-run, for myriad

strategic reasons, it desired an alliance with India. Pakistan has attempted to

play a double game with Washington by offering piecemeal cooperation in

battling the jihadists while retaining its jihadist card. But this is becoming

an increasingly difficult balancing act for Pakistan, as India and the United

States lose their tolerance for Pakistan’s Islamist militant franchise and the

state’s loss of control over that franchise.

For updates

click homepage here