|

1274

Zheng He's great-great-grandfather Saiyid Ajall

Shams aI-Din (1211-79) appointed governor of Yunnan

by Mongol emperor Khubilai Khan (born 1215, ruled 1260-94) 1368

(23 January) to 24 June 1398: reign of Hongwu (Zhu Yuanzhang,

born 1328; posth. Taizu), the first Ming

emperor 1371

Zheng He born as Ma He in Kunyang, Yunnan, then

under the rule of Prince Basalawarmi, a descendant

of Khubilai Khan 1380

Zhu Di (born 11 June 1360), fourth son of Hongwu and future Emperor Yongle,

created Prince of Yan and sent to live in Beiping 1381

Ming conquest of Yunnan ; Ma He captured, castrated, and afterward consigned

to the household of the Prince of Yan 1398

(30 June) to 13 July 1402: reign of Jianwen (Zhu Yunwen, born 1377; posth.

Emperor Hui conferred in 1736), son of Zhu Biao and grandson of Hongwu, the

second Ming emperor 1399

(August) Prince of Yan rebels; Ma He wins battle at Zheng Family Dike near

Beiping 1402

(July) Defection of river fleet under Chen Xuan permits Prince of Yan to

capture Nanjing 1402

(17 July) to 12 August 1424: reign of the former Prince of Yan as Yongle (posth. Taizong, changed 1538 to

Chengzu), the third Ming emperor; Beiping renamed

Beijing in 1403 1402-1405

Ma He (renamed Zheng He on 11 February 1404) is Director of Palace Servants

with the highest eunuch rank; extensive shipbuilding begins in 1403 1405-1407

Zheng He's First Voyage (orders given 11 July 1405), to Calicut and back,

defeating Chen Zuyi at Palembang on its return (recorded on 2 October 1407,

rewards ordered 29 October) |

1407-1408

Ming invasion and annexation of Vietnam 1407

Enlargement of Beijing as an imperial capital begins 1407-1409 Zheng He's

Second Voyage (orders probably given 23 October 1407), again to Calicut and

back 1409-1410

Yongle travels from Nanjing to Beijing (23 February to 4 April 1409), and,

after a Ming army is defeated in Mongolia (23 September), he conducts his

First Mongolian Campaign (15 March to 15 July 1410) and returns from Beijing

to Nanjing (31 October to 7 December) 1409-1411

Zheng He's Third Voyage (returns 6 July 1411), to Calicut and back, with the

campaign in Ceylon 1411

Song Li completes canal from Beijing to Yellow River 1412-1415 Zheng He's

Fourth Voyage (ordered 18 December 1412) to Hormuz, with the campaign against

Sekandar on its return (recorded on 12 August

1415) 1415

Song Li completes canal from Yellow River to Yangtze River; from this time

grain transport to Beijing is entirely by canal 1413-1416

Yongle travels from Nanjing to Beijing (16 March to 30 April 1413), conducts

his Second Mongolian Campaign (6 April to 15 August 1414), and returns from

Beijing to Nanjing (10 October to 14 November 1416) 1416-1417

Yongle's last period of residence in Nanjing, to which no Ming emperor ever

returns; he travels from Nanjing to Beijing (12 April to 16 May 1417) 1417-1419

Zheng He's Fifth Voyage (ordered 28 December 1416) reaches Arabia and Africa

and returns (dated 8 August 1419) 1417-1421

Main period of building in Beijing |

1418

Founder of Le Dynasty (1418-1804) rebels in Vietnam 1421 Yongle inaugurates

Beijing as primary capital (2 February), orders a sixth voyage (3 March), and

then orders a temporary suspension (14 May) of the voyages; later he orders a

third Mongolian campaign (6 August) and sends Xia Yuanji

and others to prison (11 December); in Vietnam, founder of Le Dynasty

eliminates local rivals 1421-1422

Zheng He's Sixth Voyage (return recorded 3 September 1422) 1422 Yonglc's Third Mongolian Campaign (12 April to 23

September) 1423

Yongle's Fourth Mongolian Campaign (29 August to 16 December) 1424 Yongle's

Fifth Mongolian Campaign (1 April to 12 August) and his death, while Zheng He

is on a diplomatic mission to Palembang (ordered 27 February) 1424 (7

September) to 29 May 1425: reign of Hongxi (Zhu Gaozhi,

born 16 August 1378; posth. Renzong),

son of Yongle, the fourth Ming emperor; Hongxi recalls Huang Fu from

Vietnam 1424-1430

Zheng He is commandant (shoubei) at Nanjing, in

association with Huang Fu, and his fleet remains at Nanjing as pa rt of the

garrison 1425

(27 June) to 31 January 1435: reign of Xu an de (Zhu Zhanji,

born 16 March 1399; posth. Xuanzong), son of

Hongxi, the fifth Ming emperor 1431-14.1.1

Zheng He's Seventh Voyage (ordered 29 June 1430) and his death 1433-1436

Books by Ma Huan (Yingyai Shenglan,

1433), Gong Zhen (Xiyang Fanguo

Zhi, 1434), and Fei Xin (Xingcha Shenglan, 1436) appear, describing the countries visited

by Zheng He's fleets 1597

Luo Maodeng's novel about Zheng He, Xiyang Ji, appears 1905 Liang Qichao's article begins

modern interest in Zheng He and his voyages |

Giving Ming naval

forces ships were much smaller and due to the large numbers of ships for Zheng

He's first voyage, there was not enough wood, and timber-cutting expeditions

were ordered along the Min River in Fujian and in the upper reaches of the

Yangtze.

The entry dated 11

July 1405 in Taizong Shifu treating the dispatch of

the first expedition states simply that," The fleet consisted of up to 255

ships carrying 27,800 men, most of whom were military personnel. The Mingshi says of this voyage that "62 great ships had

been built, 44 zhang long and 18 zhang

wide." These 62 "treasure ships" were the heart of Zheng He's

fleet and had most of its carrying capacity; they are included in the 255 ships

that the Taizong Shifu indicates were constructed in

time for the first voyage. Despite the Mingshi

account, it is unlikely that the treasure ships were all of the same size, but

they would still have had plenty of room for the crews. The normal organization

of the fleet had several smaller ships assigned to each of the large ships, in

the manner made familiar by the accounts of the earlier voyages of Faxian,

Marco Polo and Ibn Battutah

The first port of

call on all of the voyages was in Champa, at the site of the modern Vietnamese

city of Qui Nhon. This city in Champa-called Xinzhou,

or "New Department," by the Chinese-was about fifteen miles from the

(now ruined) inland capital of Vijaya. The ancient kingdom of Champa (Zhancheng, or " Cham City " in Chinese) was then

ruled by King Jaya Sinhavarman V (ruled 1400-41) of

its thirteenth recorded dynasty. Champa had been losing its wars with Vietnam

ever since Vietnam gained independence in 939, but it was about to have an

intermission from these troubles; the ultimately unsuccessful Ming effort to

conquer and annex Vietnam began during Zheng He's first expedition, and while

the wars in Vietnam lasted (until 1427-28), Vietnam's enemy was China's friend.

This state of affairs covered the entire period in which Zheng He's first six

voyages took place. Even after China recognized Vietnam 's independence in

1427, China continued to support Champa, and Vietnam. Ma Huan describes a Cham

society whose domestic economy resembles that of Vietnam (palm thatched houses,

water buffalo) even as their religious practices are clearly Hindu. Since

"most of the men take up fishing for a livelihood" the society is

oriented toward the sea, and the fishermen may turn into pirates and smugglers

who were difficult for the institutionally weak Cham state to control.Zheng He was showing the flag to overawe, rather

than exploring in any sense; fleets of Chinese official ships like Zheng He's

armada had not been seen in these waters since the period of Mongol rule

(though Chinese merchant ships had), and they had navigators who knew the way.

Furthermore, Zheng

He's voyages took place at a time when trading patterns in Southeast Asia and

the Indian Ocean were becoming less centralized, and major changes were taking

place in the Malay-Indonesian world, both politically and in the sphere of religion

and culture. The Chinese fleets withdrew abruptly after a comparatively brief

presence, having had little effect on long, term developments in the regions

where they had sailed.

But already before

the new Zheng He fleet arrived in Indonesian waters, rulers from the region had

attempted to forge relations with the new Ming empire, and Emperor Hongwu had

come to be frustrated at his inability to understand the complicated and evolving

politics of the Malay-Indonesian world.

A major theme in

Malay-Indonesian history is the interaction between the maritime Malays, whose

major political creation had been the trade-dependent empire of Shri Vijaya,

and the Javanese monarchies based on the rice surpluses that could best be

grown on that smaller island. During the Southern Song, Yuan, and Ming, the

realm of Singosari and Majapahit

(1222-1451) flourished on Java. The reign of its fifth ruler had ended in

rebellion in 1292; the arrival of a Mongol fleet sent by Khubilai Khan enabled

that ruler's successor to use the Mongols to overthrow the usurper and then

ambush the Mongols and drive them out. The kingdom prospered afterward, and the

chief minister who dominated its affairs during most of the next three reigns

swore a famous oath in 1331 not to rest until "the land below the

wind" (Nusantara, referring to the maritime Malay world) was subdued. The

narrative poem Nagarakertagama (1365), a major source

for Majapahit history, claims Brunei in Borneo,

Palembang in Sumatra, Pahang and other places on the Malay peninsula, Makassar

on Sulawesi, and the Bandas and Moluccas in the eastern archipelago as subject

to Majapahit. While the true nature of whatever

thalassocracy Majapahit wielded has been much

debated, under Rajasanagara (Hayam Wuruk, ruled 1350-89), during whose reign the Ming Dynasty

came to power, the Javanese kingdom was certainly able to exert military power

at least in southern Sumatra.

The proclamation of

the Ming Dynasty in early 1368 coincided with an impressive display of Chinese

naval power, since troops transported by sea established Ming authority over

the southern coast of China at the same time as the Ming main army marched overland

to capture the Yuan capital. A new dynasty reigning at Nanjing might well be

expected to revive traditional maritime connections between a regime based in

south China and southeast Asia. In reality Emperor Hongwu from the beginning

based his revival of the tribute system on his understanding of ancient

precedents, and he considered the more recent precedents of the Yuan and

Southern Song undesirable. He maintained a public posture of indifference to

wealth derived from overseas trade, and he was very suspicious of the political

and social consequences that might accompany oceangoing commerce. He welcomed

tribute missions, but only from truly independent states. He allowed trade to

take place only under official auspices and only when tribute was presented. He

prohibited private trading between Chinese and "barbarians" and

prohibited Chinese from sailing overseas. He repeated his prohibitions against

foreign trade and overseas travel frequently, and in an edict of 1394 he

admitted that, because he had prohibited even tribute missions from most

countries, Chinese merchants were sailing overseas to buy spices and aromatics.

His solution was that they should use Chinese substitutes. These prohibitions

had the effect of turning the already numerous (even if the numbers are

difficult to estimate) Chinese maritime population into pirates and smugglers,

since they could not be expected to give up their livelihood. Hence Zheng He

found Palembang under the control of a Chinese pirate fleet on his first

voyage, and the Chinese sources describe "pirates" -certainly Chinese

pirates-preying heavily on shipping in other areas.

Palembang was the dry

land nearest to the sea for the export of Sumatra 's pepper, and the wealth

generated by pepper exports had enabled the rulers of Shri Vijaya to attract

the seagoing trade of the archipelago into his port, as long as this trade was in

the hands of Arab and Indonesian shippers. The rise of a carrying trade in

Chinese bottoms during the Song had made the role of Palembang as an entrep6t

less relevant, yet it remained an important commercial center, and ironically

the vanished Maharajah had been replaced by a committee of Chinese merchants as

the local authority.

Since Hongwu had

prohibited overseas commerce, he was also concerned that tribute missions not

become a mere cover for trade, and therefore he looked for proof that entities

sending tribute missions were in fact independent countries. Jambi rather

than Palembang had become the capital of the state the Chinese still called

Shri Vijaya (Sanfoqi), even though trade was

conducted in both harbors and a dynasty still ruled Palembang in a subordinate

status. The founding of the Ming raised great hopes for the revival of trade

with China, and from 1371 to 1377 both harbors sent missions to China. In 1374

a mission came from Palembang, whose ruler called himself both king of Sanfoqi and maharaja (transcribed as manada

in Chinese) of Palembang (here called Baolinbang);

Hongwu formally invested this unnamed person as king and granted him a calendar

and other gifts. In 1377 Hongwu approved the request of the ruler of Jambi

(also called Malayu or Malayu-Jambi)

for investiture as ruler of Sanfoqi. Java protested

that Sanfoqi was a dependency of Java and waylaid and

murdered the Chinese embassy sent to confer this investiture. The events of

1377, sometimes described as a Javanese conquest of southern Sumatra, seem in

fact to have been more like a firm reassertion of a suzerainty established

earlier.

Hongwu, furious that

he had been deceived, cut off relations with Sanfoqi

for twenty years. In 1380, when he executed his chancellor Hu Weiyong and massacred hundreds of high officers and their

families whom he accused of involvement in Hu's crimes, intrigues with

foreigners and illicit trade in connection with the tribute missions were a

major element in the accusations. Foreign rulers, he felt, often conspired with

merchants to turn tribute missions into occasions for trade, and for that

reason tribute missions from foreign countries were often rejected. Chinese

missions to Southeast Asia during 1377-97 went only to countries that could be

reached by land.

Sometime between 1377

and 1397, probably in 1391-92, Java expelled the now subordinate but still

hereditary ruler of Palembang from his capital, compelling him to begin the

journey that transformed him into the founder of Malacca. Trade unauthorized by

Ming China continued to sail to and from Palembang, and in 1397 the old emperor

sent an angry letter by way of Thailand to Java, ordering the Majapahit king to order the Palembang ruler to mend his

ways. Instead, Java appointed a "small chief" to manage affairs in

Palembang, where things were rapidly slipping out of Javanese control partly

because of the influx of Chinese merchants. "At this time"-the Mingshi says-"Java had already overthrown Shri Vijaya

(Sanfoqi) and annexed the country, changing its name

to Old Harbor Uiugang). But after the demise of Shri

Vijaya, there was great disorder in the country, and Java also was not able to

hold on to all of this territory. Chinese people residing there temporarily

more and more often came to live there permanently. There was Liang Daoming, originally of Nanhai

District in Gllangdong, who had lived in this country

for a long time. Several thousand families of soldiers and people from Fujian

and Guangdong, who had sailed across the sea and joined him, selected Liang Daoming as their leader. This was taking place while China

was distracted with the civil war that followed Hongwu's death. By the

beginning of the Yongle reign, Palembang had become a southeast Asian city

ruled by an overseas Chinese community drawn from the Chinese maritime

population whose oceangoing trade Yongle's father had tried to prohibit.

In 1405 Yongle sent

an official, a native of the same county as Liang Daoming,

to summon the latter to court. Liang Damning came to court, presented tribute

in local products, received imperial gifts, and returned. In 1406 Chen Zuyi,

described as a "headman" (toumu) of the Old

Harbor and "also" (like Liang Daoming)

originally a native of Guangdong, sent his son to court with tribute; Liang Daoming sent a nephew. "Even though Chen Zuyi had sent

tribute to court, he committed piracy on the high seas, and tribute missions

going to and fro suffered from this." Returning

from his first voyage in 1407, Zheng He defeated and captured Chen Zuyi. Zheng

He had been warned about Chen Zuyi's piracy by Shi Jinqing,

another member of the Chinese community at Palembang, whom the Ming court then

appointed as its chief. Liang Daoming's fate is

unknown.

Palembang's previous

hereditary ruler Paramesvara, alias Iskandar Shah, by then had ended his

wanderings and had established himself as ruler at Malacca. His career

consisted of three years in Palembang (1388-91), six years in Singapore

(1391-97), two years en route to Malacca (1397-99),

and fourteen years as ruler in Malacca (1399-1413), making up the full

twenty-five years of rule ascribed to him by the Malay sources. Originally at

Malacca he was subject to Thailand, with an annual tribute of 40 Chinese ounces,

or liang, of gold, an item confirmed by both the Mingshi

and Ma Huan. In 1404 the eunuch Yin Qing was sent as envoy to his land, and

Paramesvara (Bailimisula), "very happy" at this, promptly sent back

an embassy with tribute in local products. His reward the following year, in

which Zheng He commenced his first voyage, was Ming investiture as king of

Malacca. Malacca collaborated enthusiastically with the treasure voyages: Ming

China, after all, had recognized their royal status; that, plus Zheng He's

fleet, protected Malacca against any reassertion of Thai overlordship.

Paramesvara's death in 1413 was reported to the Ming emperor in 1414 by his

son, whom the Ming recognized as the second king of Malacca (1413-23). In 1424

Paramesvara's grandson received Ming confirmation as the third king of Malacca

(1423-44). He was stranded in China from 1433 to 1435 with the other foreign

rulers and ambassadors who had traveled to China on the final voyage. Soon

after his return to Malacca in 1436 he embraced Islam and took the name Sultan

Muhammad Shah, and Malacca prospered in his reign and those of his successors

until the Portuguese conquest in 1511. The list of "over thirty"

countries that Zheng He is said in his Mingshi

biography to have visited has 36 names for 35 countries (Lambri

on Sumatra is duplicated in the list, as Nanwuli and Nanpoli). Four of them were substantial mainland kingdoms:

Champa, Cambodia, Thailand, and Bengal. Eleven others were in the insular or

peninsular Malay-Indonesian region, including Brunei on Borneo, Java, and

Pahang, Kelantan and Malacca on the Malay Peninsula, and six locations on

Sumatra: Palembang, Aru, Semudera, Nagur, Lide, and Lambri. Seven others are in Arabia or Africa: Hormuz, Djofar, Lasa, and Mecca (called Tianfang

or " Heavenly Square ") in Arabia, and Mogadishu, Zhubu

(Giumbo or Jumbo near present-day Kismayu in

Somalia), and Malindi on the African coast. Aden in Arabia and Brava in Africa

are both omitted from this list, though both ports were visited by Zheng He's

ships. It is unlikely that any Chinese ship traveled to Mecca 's port of Jidda,

and there is reason to doubt that the Chinese got as far as Malindi, but at

least there is no problem locating those places.

The thirteen remaining

locations all seem to be either in the southern part of the Indian peninsula

(nine) or in the islands that are relatively nearby (four). Aru to the south of

Semudera, and Nagur, Lide, and Lam bri to the north, along with Semudera,

all came to be included in the territory of the later sultanate and now

Indonesian province of Aceh. Ma Huan described all five countries as having the

same pure, simple, and honest customs as their fellow Muslims in Malacca,

except that in Nagur the people tattooed their faces. Except for Semudera, these countries were relatively poor and not

heavily populated: three thousand households in Lide, slightly over a thousand

in Lambri, and Aru and Nagur were "merely small

countries."

From Sumatra ships

would sail for Ceylon, sometimes making a landfall at the Nicobar Islands to

establish the correct latitude. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands, with their

naked people in dugout canoes, are never referred to as a tributary country in

the Chinese sources. The internal problems in Ceylon that led to hostilities on

the third voyage. From southern India ships could sail to Liushan,

a term often used for the Maldives and Laccadives

collectively, but Bila and Sunla have been

tentatively identified as Bitra and Chetlat atolls, respectively, both in the Laccadives. Whether or not Liushan

included the Maldives, it was also "merely a small country" and

"one or two treasure ships from the Middle Kingdom went there and

purchased ambergris, coconuts, and other such things," according to Ma

Huan, whose use of the term "purchased" here is another indication of

the private trading that went on on Zheng He's

expeditions.

Of the remaining nine

countries, all on the Indian mainland, three are certainly identified and have

substantial chapters in Ma Huan's account. They are Calicut, Cochin, and

Quilon, which Ma Huan calls Xiao Gelan, or "Lesser" Quilon. Calicut

was then the most important trading center in southern India, and Ma Huan calls

it the "Great Country of the Western Ocean." Calicut was the most

distant destination reached by Zheng He's fleet on its first three voyages. To

get there the fleet, having sighted the mountains of Ceylon from far at sea,

would either pass south of the island or make a port call there, then sail up

the west coast of India from Cape Comorin at the southern tip of the

subcontinent.

On the mainland of

India, the fleet would first reach Quilon, whose people Ma Huan, and the Mingshi following him, calls "Chola" or Suoli, which normally refers to speakers of Malayalam, but

Ma Huan did not distinguish between Malayalis and 'LlInils. Ma Huan misidentifies the people of Quilon as

Buddhists; since they "venerate the cow" they are clearly Hindu.

Quilon was only a

small country, but Cochin further up the l'oast was

Calicut 's closest commercial competitor. Cochin 's people are also

"Chola" and Hindu. The class structure was identical to Calicut 's,

headed by an elite (Nanlwn) of Brahmans, including the king, followed by

Muslims members of the trading castes, "who are all rich people"

according to the Mingshi. And the Mugua

who were very poor and earned their livingS as

fishermen and coolies; they lived by the sea in huts and by law were no more

than three feet high.

In contrast to the

variety of goods produced in Calicut, Cochin 's only product was topper. Both

Calicut and Cochin had a matrilineal system of secession to their thrones, each

king being normally followed by a sister's son; this tradition was maintained

in the princely ties of Travancore and Cochin under the later British Raj.

Other states that

are located on the mainnland of India are

"Greater" Qui/on (Da Gelan), Chola (Suoli),

of the Western Ocean (Xiyang Suoli),

Abobadan, and Ganbali. The Mingshi have a few lines appended to another entry.

"Greater" Quilon, Chola, Chola of the Western Ocean, and Iiayile were all in the general area of southern India

usually referred to as the Malabar and Coromandel coasts. While their exact

locations are uncertain, they were on the general itinerary of a fleet whose

main destination was Calicut and whose other known stopping points included

Ceylon, Quilon, and Cochin.

Some writers have

seen Ganbali as Cambay in Gujarat, "the Kambayat of the Arabs." The Zhufan

Zhi of the Song writer Zhao Rugua has a chapter on

Gujarat, a commercially important region on the northwestern coast of India

that both Ma Huan and Fei Xin ignore. The port city of Cambay sits at the head

of a long, funnel-shaped bay that concentrates the daily tides into a wavelike

bore that is a considerable hazard to navigation. Zheng He's largest ships were

most comfortable in smooth tropical seas and brown waters like the river

leading to Palembang; they would have been at risk in a tidal bore or other

rough waters. Ganbali has also been identified as

Coimbatore in southern India. This city is not only inland but, unlike Nanjing

and Palembang, both of which are inland yet very important in Zheng He's story,

it cannot be reached by water.

If Ganbali was Coimbatore and Zheng He visited it, he had to

do so by going overland. This is not an insurmountable objection; Zheng He was

certainly on land when he fought his battles in Ceylon and against Sekandar in Sumatra, but it is nonetheless unusual that

Coimbatore should be the only one of Zheng He's destinations that could not be

reached by sea. Cape Comorin, at the southern tip of India , is another

possibility for the location of Ganbali and nearby Abobadan. Cape Comorin is transcribed on the Mao Kun map

included in the Wubei Zhi as Ganbali

Headland (tou). 'This problem cannot be resolved

conclusively, but a location in southern India for both places would be most

consistent with the general pattern of Zheng He's voyages.

In the

Malay-Indonesian world the voyages of Zheng He, had an impact by contributing

to the rise of Malacca. Elsewhere Zheng He's voyages had a less lasting

influence. Major continental monarchies like Thailand and Bengal were not

trade-dependent and would have sought or avoided diplomatic relations with

China for their own reasons, regardless of the presence or absence of Zheng

He's fleet. For the smaller, weaker, and more trade-dependent coastal states of

India , Arabia, and Africa, and the islands of the Indian Ocean the presence of

Zheng He's huge ships and the powerful army they transported was overwhelming

but ephemeral. Zheng He's mission was to enforce outward compliance with the

norms of China 's by now ancient tributary system of foreign relations. Most

rulers were wise enough to comply, and they benefited both from outright

Chinese gifts and from the opportunities for illicit trade that Zheng He's

large-capacity ships no doubt provided. When Zheng He's fleets stopped sailing,

China 's diplomatic relations with these countries ceased.

Zheng He's first

three voyages kept his ships and men in continuous overseas deployment from

1405 to 1411, "Broken by two brief periods of turnaround in China in 1407

and 1409. Each of the three voyages took the same basic route: to Champa, up

the Straits of Malacca to northern Sumatra, then straight across the Indian

Ocean to Ceylon and on to Calicut and other destinations on India's southwest

coast. The outward voyage coincided with the winter monsoon, and the return

voyage with the summer monsoon of the following year. Emperor Yongle took an

active personal interest in their outcome. Afterward, the building of the new

capital at Beijing-Beiling, and his campaigns in Mongolia increasingly

dominated the emperor's attention.

But Calicut was truly

"the Great Country of the Western Ocean " in the opinion of Ma Huan,

the Muslim author of the Yingyai Shenglan,

who took part in Zheng He's voyages. Its port was a free trade emporium and

point of exchange for the trans-Indian Ocean seaborne trade. The royal title of

Calicut 's rulers was Samutiri, a Malayalam word for

"Sea King" that was transcribed Shamidixi

in Chinese and later transformed by the Portuguese into the familiar

"Zamorin" of later accounts. Succession to the throne was matrilineal,

the king being succeeded by his sister's son, as in later south Indian states.

Because of both the geography of the Indian Ocean and the seasonal nature of

the monsoon winds, this trade tended to be segmented into western (from and to

the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf) and eastern (from and to Sumatra and Malaya)

halves, and Calicut had outperformed its rivals on the west coast of India in

the competition to be the port where the two halves met.

Ma Huan describes the

class systems of Calicut and Cochin in almost identical terms: the king belongs

to an upper class called Nanhun in Chinese, which is

believed to refer to (Brahman priests and Kshatriya?) warriors in combination;

the latter were very rare in southern India . Muslims are the second class

listed, followed by the Chetty class of moneyed property owners, and the ordinary

Malayalam speaking population, called Geling in

Chinese, from Kling, which usually refers to Tamils, but Ma Huan did not distinguish

the Tamil and Malayali peoples.

Muslims are prominent

in the administration of the kingdom, reflecting the fact that the kingdom

lived by trade and that (despite a Chinese presence that was to prove

temporary) Muslim sailors controlled the Indian Ocean trade. Indeed, this trade

was the major vehicle for the propagation of the Islamic faith in the

Indonesian archipelago.

The foreign embassies

who had come to China at the end of the sixth voyage (1421-22) of Zheng

Hi arrived at court only in 1423 because of the time needed to transit overland

or through the Grand Canal to Beijing . They included envoys from Brava and

Mogadishu in Africa and from Hormuz and Aden in Arabia . Since then Malacca had

sent tribute twice (1424, 1426), Semudera once

(1426), Thailand three times (1426-28), Champa, badly affected by Chinese

recognition in 1427 of the renewed independence of Vietnam-three times (1427,

1428, 1429), and the declining Majapahit kingdom on

Java four times (1426-29). Except for Bengal , whose solitary tribute mission

of 1429 was the most distant to arrive by sea in this period, those were all of

the embassies from the countries on Zheng He's normal itinerary. The virtual

cessation of diplomatic activity after 1422 indicates clearly that the

overwhelming military power represented by Zheng He's fleet-the Xiafan Guanjun, or Foreign

Expeditionary Armada-was the key to maintaining the kind of diplomatic

relationships that Emperor Yongle, at least, wanted to have with the countries

of Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean .

For the very last

voyage (1431-33of Zheng Hethere is a detailed

itinerary, Xia Xiyang ("Down to the Western

Ocean"), which is preserved in the miscellany Qianwcn

Ji ("A Record of Things Once Heard") of Zhu Yunming (1461-1527), a

reclusive scholar of the Soochow (Suzhou) area who became famous for his

unconventional views and for his attacks on the Neoconfucianism

that had become a stifling orthodoxy in his lifetime. The Qianwcn

Ji in turn was included in the collection Jilu Huibian (literally, "Collection of Records,"

published about 1617), which included many unofficial accounts of military

campaigns and related activities in the early part of the Ming .

According to the Xia Xiyang the fleet of the seventh voyage departed Longwan ( Dragon Bay at Nanjing , near the Longjiang, ' Shipyard) on 19 January 1431. Four days later

they came to Xushan, an island in the mid-Yangtze

whose current identity is uncertain, where they hunted animals by beating them

into a circle in the manner made famous by the Mongols. On 2 February 1431 they

went by Fuzi Passage (now Baimaosha channel) into the

broader waters of the estuarial Yangtze, and on the next day reached Liujiagang. Liujiagang is 184

miles from Nanjing , according to modern charts, and the fleet went slowly on

this leg of its voyage. How long they remained there is not certain, but Zheng

He and his colleagues were in no hurry, having planned to forfeit the 1430-31

winter monsoon and to spend the rest of 1431 organizing the fleet and-not

necessarily a secondary purpose-completing temples to Tianfei.

The fleet then left Liujiagang and arrived at Changle

(here called Changlegang, 402 miles from Liujiagang) on 8 April 1431 , where they remained until

mid-December. Toward the end of this period Zheng He and his associates erected

the Changle inscription, which described the

extensive work done on the Tianfei temples while the

fleet was in residence. The long layover was dictated by the need to wait for

the winter monsoon, but since the decision to begin the overseas voyage with

the 1432 winter monsoon was certainly deliberate, it is probable that the fleet

left Nanjing essentially empty and was fully ph)visioned

and otherwise fitted out at Changle. This may have

been the normal practice for all of the voyages.

The fleet went out

through Pive Tiger Passage (Wuhumen),

the normal route used by the fleet to leave the Min River estuary, on 12

January 1432 and arrived at Zhan City (Zhancheng; the

term usually refers to the kingdom of Champa, but here it refers to its capital

near present-day Qui Nhon in Vietnam) on 27 January. Zhan City was the first

overseas stop of the fleet on all seven voyages. Ma Huan says that it could be

reached from Fujian in ten days with a favorable wind, but the Xia Xiyang notes that this particular voyage took sixteen days,

which we must shorten to fifteen since neither the departure date nor the

arrival date can count as a full day of sailing. The distance sailed is 1,046

miles on modern charts, which works out to about 70 miles per day, or an

average sustained fleet speed of about 2.5 knots (one knot is 1.15 miles per

hour; the nautical mile used for computing these speeds is 6,116 feet).

The fleet left Zhan

City on 12 February 1432 and reached Java on 7 March. Here again the 25

recorded sailing days must be reduced to 24 full days. Ma Huan does not give

sailing directions, but Fei Xin gives "twenty days and nights from Zhan

City" as the duration of a typical voyage to Java. The Xia Xiyang notes that the port of destination was Surabaya (Silumayz), well to the east on the island of Java and near

the historical heartland of the Majapahit kingdom.

The distance sailed on this leg is 1,383 miles on modern sailing charts. The

fleet needed to sail west of Borneo before turning east into the Java Sea , and

the voyage to Surabaya would require tacking rather than just running before

the monsoon winds. The average speed on this leg was about 58 miles per day, or

2.1 knots.

The fleet remained in

Java waters for months, setting sail only on 13 July 1432 and arriving at

Palembang ( Old Harbor ) on 24 July. This time the Xia Xiyang

records the length of the voyage correctly as eleven days, and the distance

sailed is 756 miles from Surabaya to the mouth of the Musi River leading to

Palembang, for an average speed of about 69 miles per day, or 2.5 knots-or

perhaps somewhat faster, since the end phase of the voyage involved moving at

least some of the ships up the river to Palembang itself. One of the

unanswered questions of the Zheng He voyages concerns whether his largest ships

sailed up the river to Palembang ; the silence of the sources on this question

argues that they did, which is further indication of their shallow draught.

Again Ma Huan gives no sailing directions, but Fei Xin gives "eight days

and nights from Java" as the duration of a normal voyage to Palembang .

The fleet did not

remain long at Palembang ; it departed on / 27 July 1432 and arrived at Malacca

on 3 August after a voyage that the Xia Xiyang

reckons as seven days. The distance is 354 miles from the mouth of the Musi

River and the average speed about 51 miles per day, or 1.8 knots. This part of

the voyage included some difficult navigation: down the river from Palembang ,

through the narrow Bangka Strait , and past the Lingga

and Riau archipelagos, whose piratical maritime populations were normally a threat

to shipping but apparently not to Zheng He's armada. Ma Huan's sailing

directions to Malacca are eight days with a fair wind from Zhan City to Longya Strait ( Singapore Strait ), then two days west

(actually, northwest). Fei Xin says eight days and nights from Palembang ,

essentially the duration of the voyage in 1432.

Leaving Malacca on 2

September 1432, the fleet reached Semud era on 12

September after a voyage of (and recorded as) ten days. Semudera

is the present Lhokseumawe district in the region of

northern Sumatra , now commonly known as Aceh; it is 375 miles northwest of

Malacca. The leisurely progression of Zheng He's fleet on this leg of the

voyage works out to an average speed of less than 1.4 knots. The winds might have

been bad; Ma Huan says five days and nights with fair wind from Malacca will

get a ship to Semudera, but Fei Xin gives nine days

and nights, closer to the actual duration of this leg of the voyage in 1432.

Semudera and the little countries that were its neighbors were

more important for their location than for their wealth or their products, and

Ma Huan wrote that Sell1udera was "the most important place of assembly

[for ships going to[ the Western Ocean ." On 2 November 1432 Zheng He's

fleet set sail from Semudera, and on 28 November it

reached Beruwala (Bieluoli;

given in a note in Xia Xiyang) on the west coast of

Ceylon after a 26-day voyage that the Xia Xiyang

incorrectly records as 36 days. This voyage is 1,096 miles for modern ships,

and Zheng He's fleet in late 1432 traveled it at an unimpressive average speed

of 42 miles per day, or 1.5 knots. This was the most frightening leg of the

voyage. Cyclones develop in the Bay of Bengal and the adjoining sections of the

Indian Ocean, and voyagers in Zheng He's day had no way to predict them other

than by a general awareness of the seasons. The fleet was far from land in all

directions, calculating its Course by dead reckoning and relying on the help of

the Goddess for its safety; the references to immense waterspaces

and huge waves.

The fleet left Ikruwala on 2 December 1432 and arrived at Calicut on 10

December. The Xia Xiyang reckons the voyage as nine

days, which we must shorten to eight. The length of this leg was 408 miles,

giving an average speed of 51 miles per day, or 1.8 knots.

On 14 December then,

the fleet left Calicut bound for Hormuz, which they reached on 17 January 1433

after a voyage that the Xia Xiyang reckons as 35

days, which we must reduce to 34 full days. The elapsed distance was 1,461

miles, which works out to an average speed of 43 miles per day, or 1.6 knots.

Ma Huan gives 25 days and nights from Calicut (and Fei Xin an utterly

improbable ten days and nights) as the duration of a normal voyage.

Hormuz is the

westernmost destination mentioned in the Xia Xiyang,

and the fleet, or at least the main poriipn of it,

remained there for less than two months, beginning its return voyage on 9 March

1433. Reference to other sources, primarily the Mingshi,

however makes it seem that seventeen countries, other than the

eight destinations listed in the Xia Xiyang, were

visited by ships and/or ambassadors connected with the expedition. In the five

cases of Canbali (Coimbatore ), Lasa, Djofar, Mogadishu , and Brava, the Mingshi

explicitly mentions Zheng He in connection with the seventh expedition.

The visit of elements

of Zheng He's fleet to Thailand on the seventh voyage is not mentioned in the Mingshi, but the enduring relationship of Thailand with

Ming China paralleled Zheng He's voyages rather than being a part of them in

the strict sense. The little countries of Aru, Nagur, Lide, and Lambri were near neighbors of Semudera

in northern Sumatra , and they certainly received visits from one or more of

Zheng He's ships as the armada passed through. Whether the Andaman and Nicobar

island chains should properly be called a "country" might be debated,

but the fleet's visit there is solidly attested by Fei Xin's account, dated

within the 26-day period of the fleet's passage between Sumatra and Ceylon.

Quilon and Cochin are on the way to Calicut, and Coimbatore (if it was Canbali) could be visited only by someone who went overland

from Calicut . For other reasons it seems likely that a substantial detachment

of the fleet operated from Calicut after Zheng He took the main body to Hormuz,

so an overland mission of that kind was possible even if it was not led by

Zheng He in person.

This accounts

for nine of the seventeen countries, in addition to the eight destinations

mentioned in the Xia Xiyang, that were probably visited

by Zheng He's last expedition. The other eight are Bengal, the Laccadive and

Maldive island chains, four locations in Arabia (Djofar,

loasa, Aden, and Mecca) and two in Africa (Mogadishu

and Brava). The eunuch Hong Bao, one of Zheng He's colleagues and collaborators

in both the Liujiagang and Changle

inscriptions, and the Chinese envoy to Thailand in 1412, was involved with both

Bengal and Mecca and perhaps with the others.

It seemed strange,

that the chapter on Bengal came near the end of Ma Huan's book, after Aden and

before Hormuz and the final chapter on Mecca . This argument adds to the

circumstantial evidence supporting a detached role for Hong Bao's squadron, but

there is no reason to believe that the breakup of the fleet occurred before Semudera. Hong Bao's squadron, including Ma Huan, went

straight from Semudera to Bengal and then back around

India to Calicut , arriving there after Zheng He and the main fleet had gone on

to Hormuz. It would have to have been a powerful squadron to overawe Bengal ,

and this might have provided enough ships for later detachments to African and

Arabian destinations.

Bengal's king

Ghiyath-ud-Din (Aiyasiding)

sent a tribute mission to China in 1408; in 1412 another embassy from Bengal

announced the death of Ghiyath-ud-Din and the

succession of his son Sa'if-ud-Din

(Saiwuding). In 1414 his successor Jalalud-Din (1414-31)-described merely as "the

succeeding king" by the Mingshi-had sent the

giraffe described as a qilin to China, and the

following year Emperor Yongle sent a ¡®Grand Director¡¯, who had accompanied

Zheng He on his second and third voyages, to confer

presents on "the king of this country and his queen (or queens; fei) and ministers (dachen).

The Mingshi account of Bengal then skips from 1415 to 1438,

when they sent another qilin; after one more mission

in 1439, tribute missions from Bengal ceased. By then Shamsud-Din

Ahmad (1431--42) was king. When Ma Huan visited the country in 1432, he found

Bengal hot, wealthy, and densely populated and speaking Benga]i (Banggeli). He mentions that

two crops of grain could be grown in one year, and he describes as an oddity

the Muslim lunar calendar without intercalary months, something one would think

that a Muslim like Ma Huan would have encountered before. He notes with

approval government institutions that remind him of China : punishments that

include beating with the light or heavy bamboo and banishment, officials with

ranks (guanpin), government offices (yamen), and

documents bearing seals (yinxin).

Hong Bao and Ma Huan

are next seen at Calicut .Ma Huan's chapter on Mecca (Tianfang)

concludes:

In the fifth year of

Xuande (1430) an order was respectfully received from the imperial court that

the Grand Director and eunuch official Zheng He and others were to go to the

foreign countries to open and read the imperial commands and bestow gifts and rewards.

A detached squadron [of the fleet] came to the country of Calicut. At this time

the eunuch official and Grand Director Hong Bao saw that the said country had

sent men to go there. He thereupon selected an interpreter and others, seven

men in all, and sent them bearing as gifts musk, porcelains, and other things.

They joined a ship of the said country and went there. They returned after a

year, having bought various unusual commodities and rare valuables, including qilin (presumably giraffes, as usual), lions, "camel

fowl" (tuoji, a common term for ostrich), and

other such things. Also they painted an accurate representation of the Heavenly

Hall. rAil of these itemsl

were returned to the capital. The king of Mecca (Moqie) also sent official ambassadors with local products,

and [these were] accompanied by the interpreter land the others, in all] seven

men who had originally gone there, and these were presented to the Court.

An entry for Mecca,

under the same name Tianfang ("Heavenly

Cube," referring to the Qa'aba) that Ma Huan

uses to head his chapter, appears in the very last chapter of the Mingshi and is clearly derived from Ma Huan's account,

which it repeats in slightly more elegant language. A squadron of the Chinese

fleet arrived in Calicut , and men from the squadron joined a Calicut ship

already scheduled to travel to Mecca . There they bought strange gems and rare

treasures, as well as giraffes, lions, and ostriches for their return.

"The king of that country also sent servants to accompany them as

ambassadors coming with tribute to the [Ming] court," and the emperor

"rejoiced and gave them even more valuable gifts [in return]."

This Mingshi passage clears up the references to the "said

country" and "there" in Ma Huan's account, and it confirms that

the Chinese who went to Mecca did not go on a Chinese ship. Aden therefore is

as far as the Chinese fleet, or any part of it, sailed in that direction. It is

certainly peculiar that the only strange and rare things that are mentioned by

name as having been "bought by" (rather than presented to) the

Chinese visitors (who are not described as envoys) are three fauna (giraffe,

lion, ostrich) typically associated with Africa rather than Arabia. Yet Ma

Huan's description of Mecca contains so much convincing detail that it is

difficult to doubt that he saw it in person.

To get to Mecca , Ma

Huan relates, one sails three months from Calicut to the port of Jidda and then

journeys overland to Mecca. All the people speak Arabic (Alabi). The Great

Mosque bears the "foreign" (fan) name of Qa'aba

(Kaiabai), and near it is the tomb of Ishmael

(Isma'il, Simayi). The Muslim pilgrimage and its

ritual of circumambulating the Qa'aba are described,

and the city of Medina is mentioned, though Ma Huan errs in making it only a

day's journey from Mecca.

Since Hong Bao from

Calicut sent the seven intrepid travelers on their voyage to Mecca, it is

probable that he also sent squadrons or detachments of the fleet to Djofar, Lasa, and Aden on the south coast of Arabia and to

Mogadishu and Brava on the Somali coast. All these locations had been visited

previously, beginning with the fifth voyage, and the sailing directions for all

of them in the Mingshi are various distances from

Calicut (Djofar, Lasa, Aden), Quilon (Mogadishu), or

Ceylon (Brava). The Maldives are also located with reference to Ceylon. One

therefore imagines that the fleet, many of whose leading personnel had sailed

these waters before, had peeled off detachments as it rounded Ceylon and

southern India and had left a substantial squadron in Calicut under Hong Bao

while the main body under Zheng He went on to Hormuz. The wording of the Mingshi entry for Mecca, the vague sailing directions given

for Malindi ("a long way from China"), and the lack of sailing

directions for Zhubu (located correctly as being near

Mogadishu), argue that squadrons of Zheng He's fleet never visited these

destinations, even though they were known to exist, and that envoys (or

merchants posing as envoys) from these nations made their way to pickup points from which they could be transported to China

on Zheng He's ships. It might be noted that the Mingshi

does have entries on Portugal (Folangji, whose

location is "near Malacca"), the Netherlands (Helan, located

"near Portugal"), and Italy (Yidaliya,

"located in the Great Western Ocean, and not communicated with since

antiquity"), none of which was visited by Zheng He's fleet even though a

later Chinese reader might think they had been from the description of their

locations in the Mingshi.

The Xia Xiyang says that the main body set sail from Hormuz on 9

March 1433 and arrived in Calicut on 31 March, calling this a voyage of 23

days, which we must reckon as 22, for an impressive average speed of about 66

miles per day (1,461 miles in all), or 2.4 knots. We must infer that the

squadrons sent to the other destinations had already assembled at Calicut , for

the entire fleet did not remain long. On 9 April it departed Calicut , and on

25 April it reached Semudera. Again the 17 days of

the Xia Xiyang must be reduced to 16 to account for

the arrival and departure dates not being full days of sailing. There is no

mention of a stop at Beruwala on Ceylon on the way

out, and really no time for a stop there or at any of the other south Indian

ports that Zheng He's fleet had visited previously, because now the winds and

waves were cooperating and the fleet, no doubt running straight out before the

southwest monsoon, averaged 93 miles per day, or 3.4 knots, over a stretch of

open ocean that J. V. G. Mills calculated at 1,491 miles. Six days later, on 1

May, the fleet left Semudera and arrived at Malacca

on 9 May; once again reducing the length of the 375-mile voyage from nine days

to eight, the fleet's average speed was 47 miles per day, or 1. 7 knots.

The next entry in the

Xia Xiyang says "fifth month, tenth day (28 May

1433): returning, [the fleet I arrived at the Kunlun Ocean ," referring to

the seas around Poulo Condore

and the Con Son Islands off the southern tip of present-day Vietnam . The fleet

had only reached Qui Nhon or Zhan City sixteen days later, on 13 June. Mills

calculates the entire distance from Malacca to Qui Nhon as 983 miles and notes

cautiously that "we are not told how many days were taken" on this

leg of the voyage. It seems more likely that the fleet left Malacca on 28 May

and proceeded to Zhan City at a respectable average speed of 61 miles per day,

or 2.2 knots. The word hui (returning) had been used to refer to the fleet's

departure from Hormuz, and its presence here suggests that the date of the

fleet's arrival in the Kunlun Ocean has dropped out in the recopying process.

Accepting the text as it stands would require the fleet's leaving Malacca after

a stay of only a few days and then spending sixteen days moving up the Champa coast

at a much lower than average rate of speed.

The fleet spent only

three full days at Zhan City and then set sail on 17 June, the first day of the

sixth lunar month. The Xia Xiyang records several

sightings on the next leg of the voyage, incidentally providing confirmation

that the navigators of Zheng He's fleet were happy to sail by landmarks when

they could find them, rather than by dead reckoning. The fleet did not anchor

until it came to Liujiagang (here called Taicang,

from the name of the prefecture) on the 21st day, or 7 July 1433. Mills reckons

this leg at 1,429 miles; Zheng He's fleet had accompliskf:d

the voyage in 20 days at an average speed of 71 miles per day, or 2.6 knots.

The average speed on

these thirteen measured legs of the seventh voyage was 58 miles per day, or 2.1

knots. The better performance on the Calicut to Semuclera

leg of the return voyage probably reflects the full force of the monsoon winds

driving the ships. The Chinese term shunfeng used in

the sailing directions found in the sources, which Mills translates as

"with a fair wind," might also be translated as "running before

the wind." It implies wind from straight aft or on either quarter, so that

the ship is not delayed by tacking.

By the standards of

Western navies during the sailing ship era, these speeds are not high. In 1805

Lord Nelson with ten ships of the line-large warships designed for fighting

power rather than speed-crossed the Atlantic at an average speed of 135 miles per

day, or 4.9 knots. Mid-nineteenth-century clipper ships, during a period in

which sail and steam were in serious competition, often achieved sustained

speeds in the double digits.

According to the Xia Xiyang, the fleet commanded by Zheng He "arrived in

the Capital" on 22 July, and five days later its personnel were rewarded

with ceremonial robes, other valuables, and paper money. These events are not

mentioned in the Xuanzong Shilu, but the latter source does have one final

entry related to Zheng He's voyages: Xuande, eighth year, intercalary eighth

month, xinhai, the first day of the month (14

September 1433). The king of Semudera Zainuliabiding (Zain al-'Abidin) sent his younger brother Halizhi Han and others, the king of Calicut Bilima sent his

ambassador Gebumanduluya and others, the king of

Cochin Keyili sent his ambassador Jiabubilima

and others, the king of Ceylon Bulagemabahulapi

(Parakramabahu VI) sent his ambassador Mennidenai and

others, the king of Djofar Ali (Ali) sent his

ambassador Hazhi Huxian

(Hajji Hussein) and others, the king of Aden Mowukenasier

(AI-Malik az-Zahir Yahya b. Isma'il) sent his

ambassador Puha and others, the king of Coimbatore (Devaraja) sent his ambassador

Duansilijian and others, the king of Hormnz Saifuding (Sa'if-ud-Din) sent the foreigner

(fcmren) Malazu and others,

the king of "Old Kayal" (Jiayile) sent his

ambassador Aduruhaman (Abd-ur-RahnJ;]n) and others, and the king of Mecca (here Tianfang) sent the headman (toumu)

Shaxian and others. [They all] came to court and

presented as tribute giraffes (qilin), elephants,

horses, and other goods. The emperor said: "We do not have any desire for

goods from distant regions, but we realize that they [are offered] in full

sincerity. Since they come from afar they should be accepted, but [their

presentation] is not cause for congratulations."

The emperor's remarks

are not as ungracious as they seem; the "congratulations" that he

rejects are the flattery of officials and courtiers to the effect that his

virtuous rule has attracted yet another qilin to

China. Yet obviously the emperor's remarks do not have the "full

sincerity" that he claimed to detect in the presentation of tribute. The

emperor himself had noted that tribute missions from the Western Ocean

countries had ceased after the sixth of Zheng He's voyages, and he certainly

understood that the tribute missions whose offerings he was disparaging were

the result of the reappearance of Zheng He's armada in those waters. This

final, if oblique, reference to Zheng He's expeditions in the primary sources

is thus added proof that the function of the voyages was to enforce outward

compliance with the forms of the Chinese tributary system by the show of an

overwhelming armed force. The emperor did not live to see the long-range

consequences of this, but the tribute missions from the Western Ocean countries

had again ceased, this time forever.

From China to the rest of the world

China is only

slightly smaller than the United States has however ninety-five percent of its

population is concentrated in the eastern one third of its territory. Natural

landscapes have a lot to do with this, people tend not to agglomerate in icy

mountains or in arid deserts-but the distribution is also a matter of

historical geography.

The imperial

dimensions of China were indeed reached during the Mongol led "Yuan" Empire, overthrown by Zheng He's Ming, that reached its

greatest dimensions during the the Qing (Manchu)

reign, which commenced in 1644 and ended in chaos in 1911. The Qing rulers

conquered much of Indochina, Myanma, Tibet (Xizang), Xinjiang, Kazakhstan,

Mongolia, eastern Siberia, the Korean Peninsula, and the islands of Sakhalin

and Taiwan.

But as Ross Terrill

already pointed out in his book The New Chinese Empire (2003), not only is

modern China the product of empire, its expansionist objectives continue. There

is Taiwan, northeast India, and other actual and latent claims; there is also the

question of Mongolia, a part of China during Qing times and now experiencing a

strong resurgence of Chinese influence, hitherto in the economic arena but

potentially in additional contexts as well. In offshore waters, China is

contesting with Japan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia the

ownership of islands whose acquisition would extend Chinese jurisdiction over

vast expanses of the South China Sea. In short, China's territorial drive is

far from over.

When Japan emerged in

the third quarter of the twentieth century as the first economic tiger on the

Asian Pacific Rim, buying ever-larger quantities of raw materials from

ever-farther sources, it was part of the American success story: stability and

democracy had enabled a defeated enemy to become the world's second-largest

economy. Wealthy Japanese entrepreneurs bought Western assets ranging from

movie studios to golf courses, art works to historic mansions. Australian

schoolchildren by the tens of thousands took Japanese language courses as

Japanese companies bought Australian commodities by the shipload. But the

Japanese economy faltered, and today it is China that is on the rise on the

Asian perimeter. From the mines of Australia to the forests of Myanmar and from

the natural gas of Malaysia to the oil fields of Brunei, China is gobbling up

unprecedented quantities of raw materials. In the process, China's political

clout in these regions grows correspondingly. International observers marvel at

the skills of a modern generation of Chinese business executives and diplomats

who are changing the political as well as the economic climate on the Pacific

Rim-and not just in Southeast Asia but in Japan and South Korea as well. Today,

for all the residual postwar anger between the two countries, Japan imports

more goods from China than from the United States, an almost inconceivable

situation just a decade ago. And China has become South.

More to the point is

China's role in competition with the United States for influence and power in

the western Pacific from Japan to Australia and from the Philippines to

Myanmar. The United States has been the long-term stabilizing force, its

postwar relationship with Japan fostering democracy there and creating the

setting for one of the twentieth century's great economic successes, its

military presence in South Korea protecting one of the Pacific Rim's early

economic "tigers" while it prospered and advanced toward democratic

governance, and its special relationship with Taiwan precluding a Tibet-like reannexation by Beijing (and nurturing still another

economic tiger). America's military presence in the Philippines until 1991,

abandoned when Mount Pinatobo's giant eruption destroyed its air and sea bases

on Luzon Island even as the Philippine Senate was weighing continuation of the

United States presence, dissuaded China from a greater aggressiveness in its

now-renounced claims to all of the South China Sea. And Washington's close

relationship with Singapore has been another part of this geopolitical

framework.

In this new century,

however, the picture is changing. Late in 2004, President G. W. Bush announced

plans to withdraw United States military forces from overseas bases including

those in Japan. The Japanese, meanwhile, were bolstering their antimissile capacity

in the face of North Korea's nuclear program and rocket tests. United States

troops in South Korea were to be partially relocated from the shadow of the DMZ

and partially withdrawn, possibly to Guam. Taiwan, its economy in difficulty,

was clearly a lower priority. Meanwhile the Chinese, always complaining of the

asymmetry between the United States presence in East Asia and the Chinese

absence from North America's Pacific Rim, scored a coup when Panama awarded a

contract to a Hong Kong company to operate and modernize the ports at both ends

of the strategic Panama Canal, recently vacated by the Americans. And be

prepared for other evidence of China's growing presence in this hemisphere.

China has recently been forging closer ties with Venezuela as well as Grenada

and Dominica, formerly supporters of Taiwan. For China, the Caribbean is full

of opportunity.

Listen to Southeast

Asians from Thailand to Indonesia today, and you hear an oft-repeated refrain:

China is a potential bulwark against an America whose actions and motives are

troubling. The growing Chinese presence combines economic stimulus with

political reassurance. Unburdened by human-rights or environmental concerns,

China trades actively and increasingly with Myanmar's military junta, ensuring

the generals' security (raise this issue, and you will get questions about

democracy in Saudi Arabia). Talk about North Korea's nuclear threat, and it is

clear that fears of an Iraq-style intervention at the Pacific end of the

"axis of evil" play into China's hands. China's star on the Pacific

periphery is rising, and geopolitical realities are changing.

On the perilous side,

there are China's expansive past and imperial present, its

communist-authoritarian governance, its dreadful human rights record, its

demographics (the one-child-only policy is creating a surplus of tens of

millions of males), its world's-largest military, its fast-rising nationalism,

its growing demand for global raw materials including oil, its unsettled

relations with Japan, its designs on Taiwan, and its problematic role with

regard to its communist neighbor North Korea with its terrorist history and

nuclear ambitions. On the mitigating side, China, unlike the Soviet Union, does

not overtly seek to export its communist system or ideology except to SARs and

Taiwan, maintains a strictly secular society, shares with the United States a

concern over Islamic terrorism, has opened its doors to economic development,

has settled some territorial issues with neighbors, and has withdrawn farreaching maritime claims.

During the twentieth century,

when the United States and the Soviet Union were locked in a Cold War that

repeatedly risked nuclear conflict, Armageddon never happened because this was

a struggle between superpowers whose leaderships, ideologically opposed as they

were, understood each other relatively well. While the politicians and military

strategists were plotting, the cultural doors never closed: American audiences

listened to the music of Prokofiev and Shostakovich, watched Russian ballet,

and read Tolstoy and Pasternak even as the Soviets cheered Van Cliburn, read

Hemingway, and lionized American political dissidents. In short, this was an

intracultural Cold War, which reduced the threat of calamity. A cold war

between China and the United States would involve far less common ground, the

first intercultural cold war in which the risk of fatal misunderstanding is

incalculably greater than it was during the last.

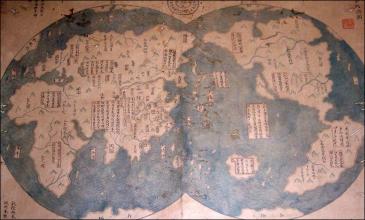

For example the above

1763 map, on which the book "1421" is based shows North and South

America, is obviously a fraud in spite of the fact that it "claims"

it is a copy of "another" map made in 1418.....

The map was bought

for about $500 from a Shanghai dealer in 2001 by a Chinese collector, Liu Gang.

According to the Economist magazine (published in Hong Kong), Mr Liu only became aware of the map's potential

significance after he read a book by British author Gavin Menzies. The map is

now being tested to check the age of its paper and ink, with the results due to

be known in February. The mapmaker's claim that he copied if from a 1418 map,

rather than from a more recent one, is clearly a fraud.

But given the fact

that the map was created during the time when China wanted to be a colonial

power competing with France and England, the map could in fact have been

politically motivated.

In the early 18th

century China started by incorporating Taiwan and by 1720 made Tibet a

protectorate. Britain seized New Amsterdam from the Dutch in 1664, renaming it

New York. France's Louis XIV reorganized New France, following Jacques

Marquette's and Louis Joliet's exploration of the Mississippi in 1673. In 1757

the Qianlong emperor restricted Western traders to a district in Canton through

the trading season ending in the spring. Traders returned to Macao until early

fall. Forbidden to learn Chinese from locals, they had to use Hong

merchants' as linguists, hence, rarely met the literati.

During the 1756-63

crisis precipitated by the English defeat of France in the Seven Years' (said

to be the first truly ‘world’-) War, Louis XV even asked one of his

favorite ministers, Henri-Léonard Bertin, how respect for the monarchy might be

improved. Bertin replied: “Sire, we must inoculate the French with l'esprit chinois”. (L. Dermigny, La Chine et l'Occident: le commerce à

Canton au XVIlle siècle, 3 vols., Paris, 1964, i. 22. 2 In his Essai sur les moeurs,

p. 38.)

One could argue

that Europeans were also not always that objective when it came to maps,

take for example, the Mercator world map stild found

everywhere today - from world atlases to school walls to airline booking

agencies and boardrooms today. If one looks at it in detail one will quickly

notice that for example where Scandinavia in reality about a third the size of

India, they are accorded the same amount of space on the map. And Greenland

appears almost twice the size of China, even though the latter is almost four

times the size of the former, and so on.

In fact the actual

landmass of the southern hemisphere is exactly twice that of the northern

hemisphere. And yet on the Mercator, the landmass of the North occupies

two-thirds of the map while the landmass of the South represents only a third!

For updates

click homepage here