By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Surprise Attack On Israel

On the morning of

Saturday, October 7, the Palestinian group Hamas carried out a surprise attack

on Israel on an unprecedented scale: firing thousands of rockets, infiltrating

militants into Israeli territory, and taking an unknown number of hostages. At

least 100 Israelis have died, and 1,400 have been wounded; the Israeli Prime

Minister declared that his country was “at war.” As Israeli forces

responded, around 200 Palestinians were killed and about 1,600 wounded.

This can be seen as a

system failure on Israel’s part. The Israelis are accustomed to knowing exactly

what the Palestinians are doing, in detail, from their sophisticated means of

spying. They built a costly wall between Gaza and the communities on the

Israeli side of the border. They had been confident that Hamas-was

deterred from launching a major attack: they wouldn’t dare because they would

get crushed because the Palestinians would turn against Hamas for causing

another war. And the Israelis believed that Hamas was in a different mode now:

focused on a long-term cease-fire in which each side benefited from a

live-and-let-live arrangement. Some 19,000 Palestinian workers were going into

Israel daily from Gaza, which was helping the economy and generating tax

revenues.

But it turns out that

was all a massive deception. And so people are in shock—and, like on Jihadist 9/11, there is this sense of, “How

is it possible that a ragtag band of terrorists could pull this off? How could

they beat the mighty Israeli intelligence community and the mighty Israeli

Defense Forces?” We don’t have good answers yet, but I’m sure part of the

reason was hubris—an Israeli belief that sheer force could deter Hamas and that

Israel did not have to address the long-term problems.

One must consider the

context for why Hamas chose to carry out this particular kind of attack. The

Arab world is coming to terms with Israel. Saudi Arabia is talking about

normalizing relations with Israel. As part of that potential deal, the United

States is pressing Israel to make concessions to the Palestinian

Authority—Hamas’s enemy. Western news outlets such as the Wall Street

Journal reported a day after the assault that Iran “helped plot” the

attack. So this was an opportunity for Hamas and its Iranian backers

to disrupt the whole process, which I think, in retrospect, was deeply

threatening to both of them. It is doubtful that Hamas would follow

Iran's dictation, but we believe they cooperate. They had a common interest in

disrupting the progress that was underway and that was gaining a lot of support

among Arab populations. The idea was to embarrass those Arab leaders who have

made peace with Israel or who might do so and to prove that Hamas and Iran are

the ones who can inflict military defeat on Israel.

Talks are going on

regarding a peace deal between Israel and Saudi Arabia and conversations about

U.S. security guarantees for Saudi Arabia. In all likelihood, a primary motivation

for Hamas and Iran was a desire to disrupt that deal because it threatened to

isolate them. And this was a perfect way to destroy its prospects, at least in

the near term. Once the Palestinian issue returns to front and center, and

Arabs around the Middle East are watching American weapons in Israeli hands

killing large numbers of Palestinians, that will ignite a strong reaction. And

leaders such as [Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince] Mohammed bin Salman will be very

reluctant to stand up to that kind of opposition. Doing so would require him to

stand up and tell his people, “This is not the way. My way will get the

Palestinians much more than the way of Hamas, which only brings misery.” That

kind of courage is, I think, too much to expect of any Arab leader in this kind

of crisis.

The Israeli

government been through this five times before, and there’s a precise

playbook. They mobilize the army, and they attack from the air; they inflict

damage on Gaza. They try to decapitate the Hamas leadership. And if that

doesn’t work in getting Hamas to stop firing rockets and enter into

negotiations to release the hostages, then I think we’re looking at a

full-scale Israeli invasion of Gaza.

Now, that presents

two problems, one is that Israel would be fighting in densely populated areas,

and the international outcry against civilian casualties that Israel would

inflict with its high-tech American weapons would shift condemnation onto the

United States and Israel and put pressure on Israel to stop. The second problem

is if Israel succeeds in a full-scale war, they own Gaza and must answer the

question: How will we get out? When do we withdraw? Whom do we start in favor

of? Remember, the Israelis withdrew from Gaza in 2005 and do not want to

return.

One thing to

know is that he prides himself on his caution regarding war. He’s cautious

not to launch full-scale wars. So we think his first preference will be to use

the air force to try to inflict enough punishment on Hamas that they will agree

to a cease-fire and then a negotiation for the return of the hostages. In other

words, a return to the status quo ante: that’s what he’ll be trying to get,

using the United States, Egypt, and Qatar to influence Hamas to stop. If that

doesn’t work, and I doubt it will, then he’s got to look at other options.

Doubt that will work,

however, is the fear that Hamas intends to get Israel to retaliate

massively and have the conflict escalate: a West Bank uprising, Hezbollah

attacks, a revolt in Jerusalem.

Yet Hamas will not

play with any Israeli response that aims to restore the status quo

ante. And regarding escalation, the party to watch most closely is

Hezbollah. If the Palestinian death toll rises, Hezbollah will be tempted to

join the fray. They have 150,000 rockets they can rain down on Israel’s main

cities, leading to an all-out war not just in Gaza but in Lebanon, too. And

everybody would get dragged into that situation.

On the other side,

Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, and the countries that signed the Abraham Accords

with Israel—the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain—all have an interest in

calming things down and getting a cease-fire because the longer this goes on,

the harder it will be for them to maintain their relations with Israel.

Despite the current

political instability in Israel, all that falls by the wayside. This is a

profound crisis of yet unknown proportions. And the prime minister is facing a

real problem, not only in defending the citizens but in avoiding blame for what

happened. And I don’t see how he can. So he’s got to find a way to redeem

himself through the conflict. He cannot afford to have his coalition's

extremist, far-right members dictate what happens because they will take Israel

into a terrible place. So either he has got to exercise control over them,

which he hasn’t been able to do yet, or he will have to remove them. [Yair]

Lapid, the opposition leader, today offered to join a narrow emergency

government, including Netanyahu’s Likud party, Lapid’s party, and the party of

[opposition leader] Benny Gantz. Netanyahu might take that as a way of

sidelining the extremists, showing responsibility, and bringing the country

together.

It is no

coincidence that this is happening 50 years, almost to the day, after the

surprise Arab attack on Israel that launched the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

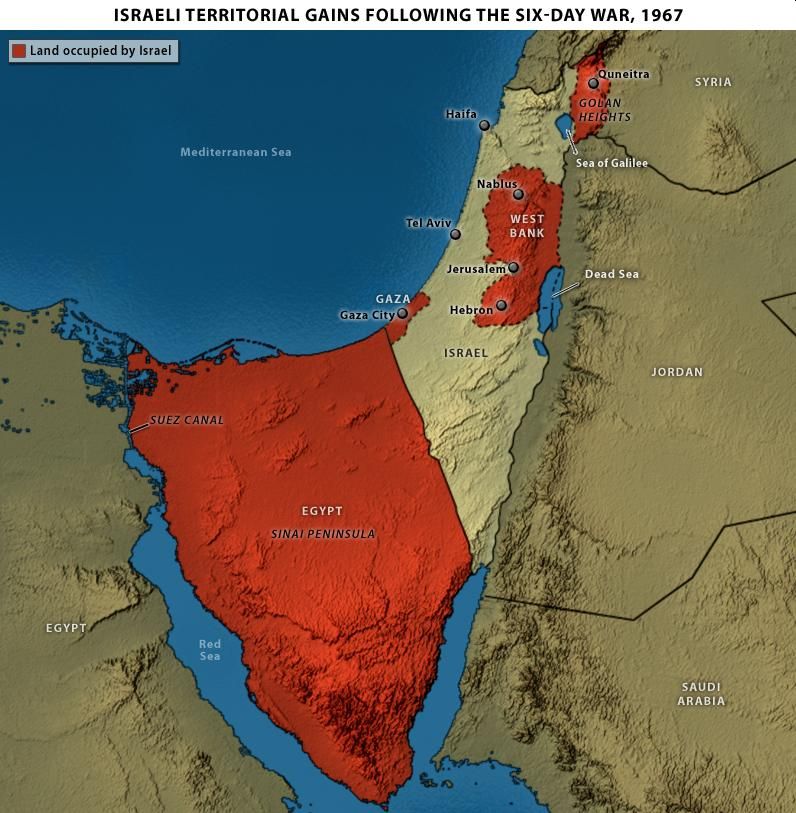

Let’s remember that,

for the Arabs, the Yom Kippur war was seen as a victory. Egypt and Syria

succeeded in taking the Israeli military by surprise, crossing the Suez Canal

and advancing on the Golan Heights to the point where many Israelis thought

Israel was finished. And so even though, in the end, Israel prevailed in that

war, the victory of the first days is still celebrated in the Arab world. So,

for Hamas to show, 50 years later, that it can do the same thing is a massive

boost to its standing in the Arab world and a considerable challenge to those

countries and leaders that have made peace with Israel in the preceding 50

years. And it’s worth pointing out that Hamas is a very different adversary. In

1973, [Egyptian President] Anwar Sadat went to war with Israel to make peace

with Israel. Hamas has launched a war to destroy Israel—or to do its best to

weaken it, to take it down a peg. Hamas doesn’t have any interest in making

peace with Israel.

It was hubris that

led the Israelis to believe, in 1973, that they were unbeatable, that they were

the superpower in the Middle East, and that they no longer needed to pay

attention to Egyptian and Syrian concerns because they were so powerful. That

same hubris has manifested again in recent years, even as many people told the

Israelis that the situation with the Palestinians was unsustainable. They

thought the problem was under control. But now all their assumptions have been

blown up, just like in 1973. And they’re going to have to come to terms with that.

Videos show the horror on the ground, including

an attack on a music festival where Israeli rescuers say

they found 260 people dead. Other clips show Israeli civilians taken hostage.

For updates click hompage here