By Eric

Vandenbroeck

Underneath the Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon (Rangoon) seen from my (Summit

Parkview) hotel room:

The Shwedagon is not just a tall spire. It has volume too,

taking up the size of a couple of city blocks. It can be seen for miles. It is

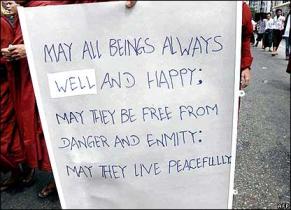

always a magical scene at night with groups of young monks, nuns, or students

praying and chanting in the light of thousands of candles. Last time I was

here, on September 24, 2007, almost 20,000 monks and nuns took part in the

largest protest in 20 years and marched at the Shwedagon

Pagoda.

Since then,

especially considering the November elections, much is changing in Yangon. But

in the countryside outside the center of Myanmar, the

ruling generals still silence their opponents and take their people down a

rabbit hole of, dictatorship, and oppression. While Suu Kyi’s NLD has secured a

majority of the contested seats, the military still holds 25 percent of the

seats in both houses. Therefore, although the NLD has control over legislation

it does not have control over constitutional amendments, which require 75

percent support from the parliament. Through it all – the worsening poverty,

the collapse of the education system, an epidemic of secret informers, the sale

of its precious natural resources to neighboring

China, the disastrous decisions based on psychics and numerology, and the

attacks on ethnic minorities, the generals continue to grow ridiculously rich.

Thus despite

the NLD's sweeping win, public doubts linger about the military's

government role given its record of political intervention and lucrative

network of businesses that could be impacted by future policy shifts.

With all the optimism

about the Aung

San Suu Kyi transition talks, it is easy to forget that Myanmar remains

embroiled in several of the world's longest-running civil wars. A divided

nation, there are no less than 15 different armed rebel groups active in

Myanmar. Even the day I arrived, authorities once again blocked human rights day

events. Considered

"Aafaltering peace process" the outgoing

government has signed ceasefires with many of the ethnic armies, but many have

broken down. For example, more than 20 years ago a ceasefire was agreed with

the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance

Army in the Kokang region of Shan state, yet ongoing fighting with that group has

cost over 100 lives and displaced thousands of civilians, many of whom have

fled across the border to China.

"Peace

starts now" was the headline splashed in capital letters across the

front page of Myanmar’s state-backed newspaper on 15 October. It was an

ambitious statement on the day the government and eight armed groups signed a

ceasefire agreement intended to end 60 years of ethnic warfare, but one that

many would dismiss as pure propaganda.

It is clear that the so called peace accord is a useful campaign tool

for the government, which is dominated by former military men and serving

officers who hold a constitutionally mandated 25 percent of parliamentary

seats. The ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party can claim it as a sign

of its commitment to reform as it goes into the 8 November elections, but even

the ceasefire’s name is misleading. The agreement can hardly be considered

“nationwide”, since it excludes the majority of Myanmar’s approximately two

dozen armed groups, including some of the most powerful ones.

Only two groups signing the accord could be considered genuine rebel

armies: the Karen National Union, KNU, and the Restoration Council of Shan

State, RCSS and its Shan State Army South. A third, the Democratic Karen

Benevolent Army, or DKBA, has, in effect, been a militia on the side of the

government since it broke from KNU in 1994. The fourth group, a Karen faction,

is small, more of a civil society organization than a rebel army.

The fifth, the All-Burma Students Democratic Front has not been a

fighting force to be reckoned with since the 1990s. The Chin National Front is

a small, mainly unarmed group, and the Arakan Liberation Party is a tiny outfit

with no presence in Rakhine State. It consists of a dozen or so people staying

in KNU areas near the Thai border and should not be confused with the Arakan

Army, which fights alongside the Kachin Independence Army, KIA, in the north.

The last of the “rebel armies,” the Pa-O National Liberation Organization is a

one-man show led by a person who lives in Chiang Mai, Thailand, who set it up

when the main rebel Pa-O National Organization/Army entered into a ceasefire

agreement with the government in 1991.

None of Burma’s main ethnic armies active in the north signed the

agreement – among them the KIA with approximately 8,000 soldiers and the

country’s largest ethnic army, the more than 20,000-strong United Wa State Army, or UWSA, and their allies in northern and

eastern Shan State. A total of about 40,000 ethnic troops is not part of the

deal with the government. Observers see the less than half-baked agreement as

little more than a face-saving gesture of the government-appointed Myanmar

Peace Center, which has received vast amounts of money from the European Union

and others. After several years of talks, the MPC needed something to show

international donors to justify what in reality amounts a failure to achieve

peace across the country.

The latest, signed to great fanfare on October 15th by President Thein

Sein, a former general, included just eight of the 15 armed rebel groups. Among

those that did not sign are the United Wa State Army,

which operates on the border with China, and the Kachin Independence Army, the

largest ethnic militia. Meanwhile, mob violence

against Muslim Rohingyas that began in 2012 in the western state of Rakhine

points to further conflict. Thousands have since fled by sea and overland,

often aided (or kidnapped) by human traffickers. And as recent as 3 Dec.2015,

the United States called for a credible, independent investigation by Myanmar's

government of reports

of military atrocities in the country's Shan State. And at the time of writing

(12 Dec. 2015) heavy fighting is going on in Kachin State (my next stop).

The background

As will be detailed below, prior to British colonization, Burma or

Myanmar, as it is known today, did not exist. Rather, the region consisted of

independent kingdoms; Burman, Mon, Shan, Rakhine, Manipuri, Thai, Lao and Khmer

kingdoms were located throughout the region, and were engaged in constant

conflict.

On 12 February 1947 General Aung San expecting a handover by the

British, signed the Panglong agreement with

representatives of the Shan, Chin and Kachin people, three of the largest of

the many non-Burman ethnic groups that today make up about two-fifths of

Myanmar’s population. The agreement said that an independent Kachin state was

“desirable”, and promised “full autonomy in internal administration” to

“Frontier Areas”, as today’s ethnic states were then known. Aung San was assassinated just over five months later.

Under the 60 years of mostly military rule that followed, the spirit of the

Panglong agreement has never been honoured.

Since achieving independence in 1948, Burma has experienced near

constant internal conflict.

|

1) It was not with the hopes of achieving

significant political or economic gains that the British forces first invaded

the land which they knew as Burma - though both of these explanations were

later invoked to explain the extension and expansion of their campaigns.

Rather, the colonial army was first sent across the Irrawaddy from British

India to put an end to armed incursions by Burmese troops. Whereas later, in

the early 1960s when the complete dissolution of the union seemed an imminent

possibility. Stepping into the breach, as they had in many states in the

region during periods of (perceived) crisis or political uncertainty, was the

military. Continue… 2) Among the circumstances that contributed to the

survival of British India was that of the hill people of Burma who were

providing tough resistance to Japanese patrols and providing material

assistance to the Allied war effort. No one realized it at the time, but this

was one of the turning points of the war. Many asked themselves quietly

whether a Japanese-led Buddhist and Asian national solidarity was possible

and whether this was Burma's future. Unaware that Aung San and other young

radicals were already building a secret national army over the Thai frontier,

most Burmese watched and waited, untroubled by the small flurries of activity

among Europeans. Continue... 3) As the

Burmese Army flanked by the Japanese marched on into their homeland, Burmese

patriotic fervor sometimes took on a tinge of inter-communal hatred versus

the Karen and others. Continue… 4) Karen nationalism became very complex when the

diversity and local segmentation within the ethnic unity entered the process,

where religious dividisions plaid a decisive yet

partly concealed role. The British thus pointed to poor Karen leadership, no

sense of community and the old Karen weakness of following prophetic types of

leaders. The Karen leaders replied that it suited the British well to act confused,

thus avoiding clarification of their position and thus contributing to the

confusion. Continue… 5) Burmese supporters in London were put on their

guard in October when a Karen 'goodwill mission' arrived in town, yet rise of

communism throughout Asia weighed heavily on the minds of the British. Continue... |

6) The frontier areas would now have to be brought

within the remit of a Burmese cabinet. So, too, would control over affairs

concerning British and Indian imports. All expenditure would have to be made

subject to a vote of the lower house. The British could no longer hope to

'reserve' subjects (like the Karen or Kachin) that bore on their own

interests, as they had been doing for years. Continue… 7) The critical point during the India-Burma

Committee Cabinet meeting on 22 January 1947 in London according to Kyaw

Nyein, was not so much British commercial interests in Burma as the status of

the hill areas. Aung San was deeply suspicious of the Frontier Service

officers and Tom Driberg increased his alarm by saying that a British

government representative at Panglong might encourage the more recalcitrant sawbwas or minority tribal leaders to hold out for too

much. Continue... 8) Burma's independence and exit from the Commonwealth

had finally come to pass. Terrified by the memory of the assassination of

Aung San, Burma's youthful leaders had consulted numerous astrologers. They

had insisted that the date should be moved from 6 to 4 January and that the

proclamation itself should take place at precisely 4 o'clock in the morning

to take advantage of a favorable conjunction of the stars. Continue... 9) Under the surface of the Burmese government's

resurgence, however, the balance of power was shifting irrevocably towards

the military. Thus, a country that had once been one of the brightest hopes

for Asian prosperity, Burma soon had all but become one of the first 'failed

states’. Continue... 10) After the occupation and the end of the war

following the Japanese surrender in 1945, Japan retained a special place in

Burmese political developments. The immediate reason for this sentimental

attachment was the fact that it was Japan that had trained the "Thirty

Comrades" who were the core of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) which

actually fought against the British and contributed towards gaining

independence. The short duration of less than two-and-a half years between

the Japanese surrender and the declaration of Burma's independence in January

1948 meant that Japan was able to re-establish ties with Burma's

post-independence elite rather swiftly. The return of Japan post WWII. Continue... |

As can be seen from what is presented, World War II was to have a

dramatic impact on the Frontier Areas. Not only did British, American, Japanese

and Chinese nationalist armies enter the territory, but the semi-permeable

barriers that the British had created between the minority peoples and the

ethnic majority, the Bamar, were removed during and after the Japanese

Occupation. As it became apparent soon after the end of the war that Myanmar's

political independence was not only inevitable but imminent, elites throughout

the country began to make claims and counter-claims about the historic rights

of "their people". Ethnicity now was transformed from an object of

discussion and a principle of organization to political rallying cry. A

plethora of nationalist claims were advanced. The "federal"

constitution that the country adopted at independence in 1948 was the result of

compromises that the British had encouraged, and General Aung San achieved, at

the Panglong Conference in 1947. One of the primary requirements of the first

constitution of independent Myanmar was to reshape the state to meet those

expectations and in that it failed. Today a discussion was published stating: ‘It

Is Not Enough for Elites Simply to Get Along’.

My goal is to find out more about this including what currently is going

on outside of the core area of Burma Proper. Having spoken to some

representatives today, tomorrow I fly to Myitkyina in the Northern Kachin State

from where I will continue my investigation.

17 Dec.

2015: Myanmar P.2: A lot of the current fighting

is taking place in the area around Hpakant, not surprising one of the leading

jade-producing zones. Plus concern NLD goes the way of AFPFL in the

parliamentary era of the 1950s. To Myitkyina and

Kachin State.

19 Dec.

2015: Myanmar P.3 ethnic cleansing in Sittwe:

Among others the 969 movement (by some seen as influenced by the psywar

department) and how intolerance threatens Myanmar’s nascent transition to a

more open, democratic state. Two kinds of Monks.

On the left rural market, on the

right walking through Shan State

23 Dec.

2015: Traveling through Myanmar P.4 Shan State: Even after

having signed a ceasefire, the Burmese military continued to attack the Burma

Army and the Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army-North areas. Ethnic

rebels in the north of Burma, such as the Kachin Independence Army (KLA) and

the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), have

accused the Burmese government of actively participating in the drug trade,

whilst at the same time claiming to be cracking down on it. The Challenge of Unity in a Divided Country.

27 Dec.

2015: Traveling through Myanmar P.5:

If the Kachin have suffered the most at the hands of the Burmans in recent

years, it is the Karen who have fought them for the longest. Past the Golden Rock to Karen (Kayin) State.

30 Dec.

2015: Traveling through Myanmar P.6:

Moulmein, Orwell, Kipling, the Mon, including revisiting the bizarre insurgency

of two teenage boys. Mawlamyine and beyond.

For updates click homepage

here