By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Since coming to power

in March 2013, Xi has not hidden his grand design for China’s national

rejuvenation: to make it the greatest power in the world. He is a true

believer, born into communism and molding himself in the image of Mao, the

Great Helmsman. He used a platform of ‘anti-corruption’ to strengthen his

regional, then central, and now supreme hold on power. Now in an unprecedented

third term in office, after the Twentieth Party Congress in October 2022, Xi’s

goal is for China to displace the United States as the world’s greatest power

both in Asia and the world. The year 2049, the centenary of communist rule in

China, seems an obvious deadline for Xi. To become the number one power, China

must catch up with the West and overturn the US-led rules-based international

order.

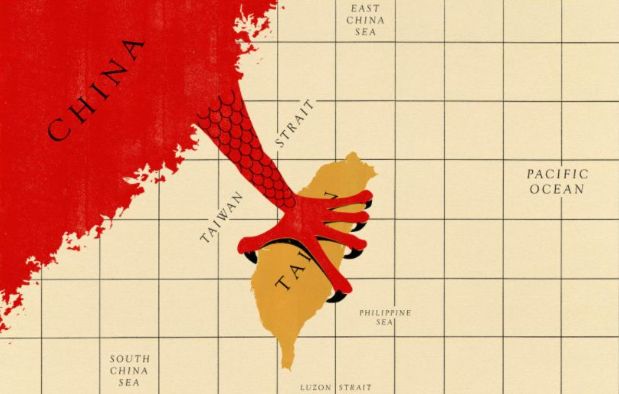

Xi’s strategy is to

protect his own rule and ‘unite’ China – which means absorbing Hong Kong and

Taiwan, by force if necessary. In his public strategic plan, ‘Made in China

2025,’ Xi identified ten key technology areas that he wants China to excel in,

including robotics, green energy production and vehicles, aerospace, and

biopharma. Xi has said that in those areas of core technology, where it would

be otherwise impossible for China to catch up with the West, the country must

‘research asymmetrical steps to catch up and overtake’ Western powers. Xi has

thus made no secret of giving his authorization to steal technological secrets.

In the decade after 2010, the FBI witnessed a 1,300 percent increase in

China-related economic espionage cases. Some of that may be explained by

increased FBI collection, and discovering more espionage going on anyway, but

that cannot explain it all. China’s cyber-hacking operations, targeting every

sector of Western society, are greater than every other major nation combined,

according to the FBI.

In July 2022, MI5’s

director general, Ken McCallum, gave an unprecedented joint public briefing

with FBI director Chris Wray at MI5’s London headquarters, Thames House. Wray

put it bluntly to the audience of assembled business leaders: ‘The Chinese

government is set on stealing your technology, whatever it is that makes your

industry tick, and using it to undercut your business and dominate your

market.’ In October 2022, President Biden effectively declared economic war on

China by imposing restrictions on high-end chips. Biden’s strategy is to

sabotage China’s race to dominate artificial intelligence (AI). As the

commentator Edward Luce pointed out, when the history of this period comes to

be written, it will likely be seen as the moment when the US-China rivalry came

out of the closet. How did we get here?

Before 9/11, the US

intelligence community was sounding the alarm about the national security

threat posed by Chinese espionage. At the turn of the century, China’s

intelligence services were conducting sustained efforts to steal American

S&T, like nuclear secrets, as national security papers held at President

Bill Clinton’s library reveal. Then 9/11 happened. Thereafter, Western

intelligence agencies overwhelmingly focused their resources on kinetic

counterterrorist operations – while downgrading collection on resurgent states

like China and Russia. According to a report published in 2020 by Britain’s

parliamentary intelligence oversight committee, in 2006–7 some 92 percent of

all of MI5’s work effort was devoted to counterterrorism, with the remainder thinly

spread across all other areas, including hostile state activities.

According to MI6’s

former deputy chief Nigel Inkster, who retired in 2006: ‘In my three-decade

career with Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service, China was never seen as a

major threat.’ In the United States, the downgrading of hostile states like

China after 9/11, at the expense of counterterrorism, was less acute than in

Britain, but there was a ‘downward glide,’ according to one NSA official

interviewed for this book on the condition of anonymity. The US intelligence

community had more resources than the British and more capacity, so shifts were

less acute. But even the US intelligence community did not give China the

attention it deserved after 9/11. According to Sue Gordon, a career CIA officer

and later one of the most senior American intelligence officials, the US

intelligence community failed to respond to what was going on in China after

9/11. That period ushered in the digital revolution, which, Gordon noted,

permanently changed the nature of intelligence and national security.

The Chinese

government grasped the opportunities provided by the digital revolution and

operationalized them. The US did not. It was still overwhelmingly focused on

terrorism and was trying to address new threats with leftover resources.

According to Michael Hayden, DCI from 2006 to 2009 (and previously director of

NSA): ‘Every day [at CIA] I woke up thinking I had to do something about China,

but there was never enough time.’ The priority given to counterterrorism within

US intelligence continued until as late as 2017.

In 2005, the

principal civilian Chinese intelligence services, the Ministry of State

Security (MSS), declared war on the US intelligence community. From that point,

according to CIA insiders interviewed, all the MSS’s best personnel and

resources were marshaled in the US, with the long-term strategic aim of

supplanting America in Southeast Asia. As the US was distracted if not consumed

by the War on Terror, the MSS’s gains were largely undetected or appreciated by

US spy chiefs. China’s strategy followed a saying, GeAnGuanHuo

(), ‘Watch the fires burn from the safety of the opposite river bank which

allows you to avoid entering the battle until your enemy is exhausted.’

Those failures were

exposed between 2010 and 2012, when Chinese intelligence broke up a CIA spy

network, reportedly leading to the detection, imprisonment, or death of around

thirty agents. Insiders describe this case as the tip of an iceberg of still-classified

US intelligence failures in China in recent years. Their causes remain unclear.

They may have arisen from the Chinese technical collection of CIA covert

communications (COCOM). More chillingly for Langley, according to some

insiders, they may have come from a Chinese mole inside US intelligence. The

spy in question may have been a former CIA case officer in China, Jerry Lee,

now convicted of espionage.

f Xi makes a

move on Taiwan, we shall find out whether the US intelligence community has

penetrated his regime in the same way it did Putin’s. China’s economic rise

this century has been meteoric. At the turn of the century, its GDP was around

$1.2 trillion. It is now $17.7 trillion. Between 2011 and 2013, China

used more cement than the United States consumed in the entire twentieth

century. The country’s high-speed trains leave Amtrak, in the dust. The

widespread belief in the West, at least at the time of the 2008 Beijing

Olympics – that China’s economic development and integration with the world

economy would lead to greater political freedom and make it a responsible

stakeholder in global affairs – has proven to be mistaken. Chinese espionage

against Western countries has accelerated since Xi took power.

Of the 160 reported

cases of Chinese spies in the United States from 2000 to 2020, over half are

since Xi took the helm. Those are, of course, just the cases detected by US

authorities. China’s industrial explosion this century was propelled by foreign

intelligence collection. This has taken the form of traditional human espionage

combined with cyber exploitations. These offensive efforts have allowed the

Chinese government to reverse-engineer manufacturing and save time and

resources on research and development. According to US intelligence (ODNI)

estimates, Beijing’s spying has saved China $320 billion in R&D costs.

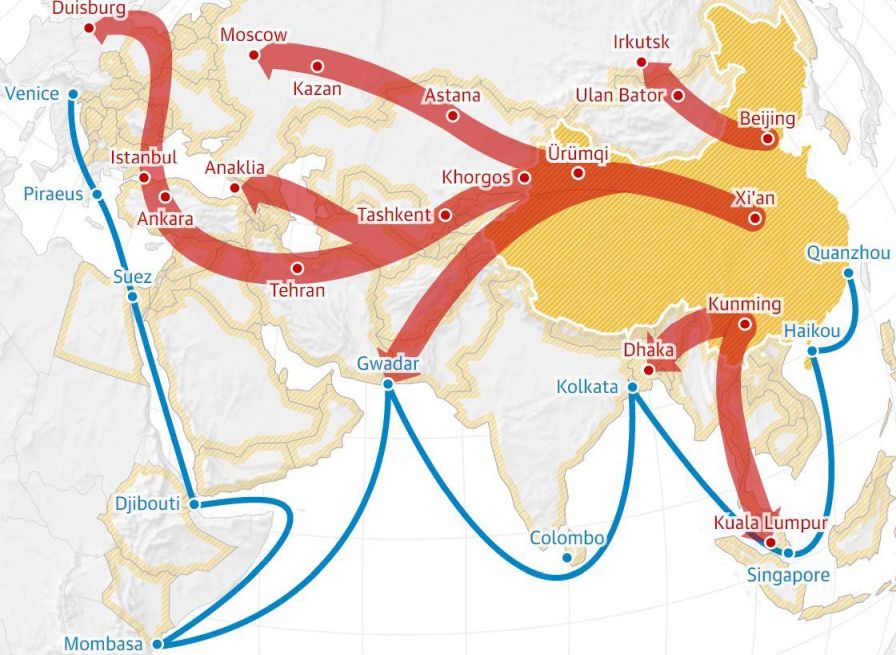

China’s massive Belt and Road Initiative, a

political and economic program to advance their interests in other regions of

the world through large investments in infrastructure, has been accompanied by

a barrage of espionage, subversion, sabotage, and disinformation.

All are designed to

further China’s grand strategy to make itself into a superpower rivaling

America. Xi’s ‘China Dream,’ his ‘Made in China 2025’ platform and the

‘Thousand Talents’ program are amped-up Soviet-like economic plans. They are

designed to make China independent of Western technology, invert the existing

world order, make the West dependent on Chinese technology, and establish China

in its rightful place as the middle kingdom, all while containing the United

States and its ‘imperialism.’ As usual with counterespionage, we only know

about spies who are caught. Take the case of a Chinese national, Xu Yanjun, who in November 2021 was successfully prosecuted in

the US for stealing technology in Europe and the United States. Beginning in at

least 2013, Xu presented himself as a businessman interested in joint ventures

with US and European companies specializing in aviation. His patient

recruitment strategy eventually worked with GE Aviation, which developed an

advanced composite aircraft engine. In March 2017, he recruited an agent in the

company, a GE engineer, who gave him sensitive IT data. Xu threw money, and a

trip to China, at his recruit.

Xu was of course not

a businessman but a Chinese intelligence

officer (again, part of the Ministry of State Security). In 2018, Xu

started to task his recruit for GE technical secrets. By this time, however,

the GE employee had alerted the FBI. Xu was arrested in April 2018 in Belgium,

where he traveled to meet his agent. If it had been successful, Xu’s espionage

would have allowed the MSS to steal valuable GE Aviation secrets, and the

Chinese government to leapfrog over a decade of hard work and billions of

dollars spent in research and development. The case shows the fusion of human

and cyber intelligence – ‘hyber.’ There are countless

other cases of Chinese ‘businessmen’ seeking joint ventures with Western

companies, using the prospect of cooperation to obtain intellectual property –

maybe an underlying source code – but then withdrawing from an agreement once it

is obtained. Western companies are left like empty shells, having given up

their IP. They often have to declare bankruptcy, with resulting job losses, in

the face of Chinese firms selling products based on their own IP on the market.

To add insult to injury, sometimes Chinese companies sell Western IP back to

the communities from which they stole it. The former head of

counterintelligence at the CIA, Mark Kelton, has put the current Chinese

espionage storm in perspective: a scale such that the United States government

has not seen since Soviet intelligence in the 1930s. Kelton’s remarks deserve

widespread attention.

Among the government

and private sector secrets that have been appropriated by China in the

twenty-first century are US missile and military aircraft designs (F-35 and

F-22), Silicon Valley software and hardware secrets, pharmaceutical patents,

and research from US universities and other institutions. A cursory glance at

the J-20, a Chinese fifth-generation fighter, reveals its similarity to the

F-22. That is not surprising, given that a Chinese national was prosecuted for

stealing its plans from Lockheed Martin. (This follows in the tradition of the

Tupolev Tu-4, a Soviet bomber, which was a clone of the famous glass-fronted

Boeing B-29 Superfortress.) It remains to be seen whether Western governments

have secretly learned the lessons of the Cold War from the FAREWELL case

described earlier: to sabotage US supply chain secrets being targeted and

stolen by a hostile state.

There are rumors that

the NSA sabotaged software made by Cisco Systems that ended up in China. To

carry out their intelligence offensive, China’s spy chiefs are deploying some

of the apparatus and methods of their Soviet predecessors. Legal intelligence officers

are stationed in Western countries under diplomatic cover. Chinese deep-cover

illegals, without diplomatic cover, pose as students at US universities,

businesspeople, or tourists. They recruit agents in the West with access to

political and economic secrets. China’s spy chiefs keep diaspora communities in

Western countries under surveillance, appeal to their ‘patriotic’ duty, and,

when that fails, use family members who remain in China to bribe and blackmail

their relatives into collecting intelligence and influencing targets. China’s

intelligence services also use a constellation of front groups in Western

countries, such as the five hundred or so Confucius Institutes across the

world, to engage in illicit activities.

As the scholar Alex Joske has shown, although they are not

ostensibly under the control of the Chinese Communist Party, they are directed

by the CCP’s United Front Work Department (UFWD) in Beijing. The UFWD,

described by Mao as one of the party’s ‘Magic Weapons,’ is the equivalent of

the Comintern. The country’s influence campaigns have

reached US and British universities, think tanks, media organizations, and

politicians, all to recruit future leaders and promote platforms favorable to

China. There are good reasons for China’s use of tradecrafts similar to that of

the Soviets. China’s intelligence services – the Ministry of State Security,

the Ministry of Public Security, and PLA military intelligence – have their

origins in the Soviet period.

The CCP famously

scrutinizes Soviet history, especially the Soviet Union’s collapse. In 2006 it

produced an eight-volume DVD set, Consider Danger in Times of Peace: Historical

Lessons from the Fall of the CPSU (Communist Party of the Soviet Union). The CCP

would undoubtedly look askance at the suggestion that it needed to learn about

intelligence from the Soviets or Russia. China has its own ancient history of

espionage, deception, and subversion on which to draw. We do not know the

extent to which China’s spy chiefs have educated themselves through their

friends in Moscow, past and present, and/or are themselves innovating. So far

as we know publicly, the West does not yet have the Chinese equivalent of

Western spies in the KGB, such as Oleg Gordievsky

or Vasili Mitrokhin, who can reveal Beijing’s

innermost intelligence secrets.

Chinese intelligence

is also naturally seeking to penetrate Western agencies themselves. The MSS has

recruited agents to infiltrate the CIA like the KGB recruited the Cambridge

Spies eight decades ago. The case of Jerry Chun

Shing Lee, a CIA officer who became a Chinese agent after he left the

agency, shows that Chinese intelligence has certainly got close. For all we

know, China’s provocative actions in the South China

Sea may be calibrated on intelligence from deep inside Washington, just as

Stalin’s provocations were in postwar Europe.

In 2019 alone, three

former US intelligence officials (from the CIA and the Defence

Intelligence Agency) were prosecuted for revealing secrets to the Chinese.

Chinese intelligence is also known to have recruited former French intelligence

officers. Has Chinese intelligence gone further and recruited current officers?

Chinese intelligence

has a database of potential kompromat for recruiting American spies of which

the KGB could only have dreamed. Beginning in November 2013, it seems, Chinese

hackers breached the databases of the US Office of Personnel Management (OPM).

They contain the most sensitive information about holders of US security

clearances – personal information that those who go through background checks

want to keep secret, sometimes even from their own families: personal finances,

substance abuse, extramarital affairs, psychiatric care, sexual behaviour, even notes to polygraph tests.

It is estimated that

the OPM data stolen by Chinese hackers pertains to millions of Americans. It

includes twenty-two million security clearance files and five million

fingerprints. All this data is now in Beijing. Former FBI director James Comey

has stated that his security clearance form has likely been stolen, providing

Chinese hackers with the addresses of every place he has lived since he was

eight, and a list of everywhere he has travelled to outside of the United

States. Chinese hackers followed the OPM breach by conducting, in 2017, one of

the largest data breaches in history: the theft of confidential data on

approximately 150 million Americans from the consumer credit reporting agency

Equifax. If you are an American, it is now more likely than not that China has

stolen your data. In 2021, the Chinese government conducted a massive hack of

Microsoft Exchange email server software. It compromised the networks of thirty

thousand American companies. According to the FBI in 2022, China stole more personal

and corporate data from Americans than hackers from every other country

combined.

The marketplace for

foreign intelligence recruitment is now LinkedIn. In some instances, former US

government employees and contractors make it all too easy for Chinese

operatives. Some proudly display on LinkedIn that they have security

clearances, effectively putting a For Sale sign on their profiles. They are

comparatively easy targets for Chinese false-flag operations, wherein officers

pose as innocuous ‘risk consultants’ offering lucrative contracts. With

relatively small government salaries, piling mortgage debts, and eye-watering

college tuition bills, for some, it will not be hard to sell out the American

dream for Chinese cash. Divided loyalties, not ideology, are the key motivation

for Americans known to have become spies since the end of the Cold War.

Fair enough for

China, we might say. They are doing what anyone else would – perhaps just

better. But that is to discount a fundamental asymmetry. The US government does

not collect economic and industrial intelligence to give its companies a

competitive advantage. By contrast, the Chinese government has integrated

‘national security’ – a slippery term – and commerce. Through legislation

passed in 2014, all Chinese citizens and companies are required, when

requested, to collaborate in collecting intelligence. In effect, this has

produced a whole-of-society espionage effort. The Chinese technology giant

Huawei, the largest manufacturer by revenue of telecom equipment in the world,

constitutes a latent platform for bulk Chinese intelligence collection.

In China, because of

a series of national security laws passed since 2015, there is no such thing as

a truly independent business. The country’s intelligence services are hidden

partners in commercial enterprises with the outside world. The story of Crypto

AG discussed in Chapter Nine, reveals how Western governments colluded with a

private encryption company to collect bulk data. It is fanciful to think that

China is not undertaking similar activities. Huawei’s hardware, integrated into

homes and offices worldwide, in appliances that are part of the Internet of

Things, provides China with unprecedented opportunities for bulk collection

through billions of interconnected and interdependent global data points.

TikTok constitutes an advanced Chinese government collection tool, masquerading

as a social media platform. It provides Beijing with a tsunami of global

information, behind the endless dance videos posted on it. It also allows China

the opportunity to shape and suppress online narratives, should it wish to do

so. It does not take much to imagine what Chinese data scientists can do with

this information, using machine learning and data mapping techniques like

social network analysis.

As with the Soviets,

a major priority for Chinese intelligence is domestic control and repression:

intrusive surveillance of citizens, the suppression of pro-democracy dissent,

indoctrination, and the incarceration of enemies, even those who pose little credible

security threat. China’s internment of about one million ethnic Muslim Uighurs

in Xinjiang, and its forced labour programmes, recall the Gulag.

The CCP goes to

comparable lengths to silence opposition and airbrush away its human rights

abuses, creating what the author Louisa Lim calls the ‘People’s Republic of

Amnesia,’ committed to destroying all popular memory of the 1989 democracy

movement in China. Just as the KGB jammed British and American radio

transmissions into the Soviet Union, today Chinese intelligence operates the

great firewall, censoring internet traffic, with online censors preventing all

internet search terms of Tiananmen Square and any online reference to the

massacre of 4 June 1989, by blocking all combinations of searches of the

numbers 6, 4, and 1989. They also blocked the Chinese word for ‘jasmine,’ the

synonym for Tunisia’s colour revolution in 2011,

incredible for a nation of jasmine tea lovers. China sells its digital

playbook, including facial recognition software used for ubiquitous

surveillance, to authoritarian regimes across the world – offering a

tried-and-tested blueprint for social control, ready for dictators to use.

Made-in-China surveillance technology is being found around the globe.

China’s doctrine of

‘winning without fighting’ (like Russia’s active measures) is designed to

influence foreign affairs to its advantage. The two countries do, however, have

different aims: Russia uses covert action to divide Western alliances and

create chaos in Western democracies, while China seeks to project a positive

image of itself as an alternative to its Western competitor, pulling foreign

countries away from the US and into its orbit. As with so much else, though,

when it comes to spying and covert actions, the CCP has taken matters to an

entirely new level compared to the past. The MSS is staffed with approximately

eight hundred thousand officials, dwarfing the KGB even at its height.

The Chinese

government has regurgitated for Covid the same conspiracy theory cooked up by

the KGB about AIDS. Whether by design or coincidence, Beijing has pushed

disinformation that COVID-19 was a bio-weapon developed by the US military. The

Chinese government has even claimed that COVID-19 originated at Fort Detrick,

the same US military research facility where the KGB claimed AIDS was

engineered. What’s old is new again.

But today there is no

need for Chinese services to plant disinformation in obscure publications, as

the KGB did. Social media now provides a quick, easy, and cheap torrent of

disinformation about the coronavirus. As with AIDS, China’s Covid disinformation

exploits existing divisions in the US and other Western societies. Western

anti-vaxxers did the heavy lifting for Chinese trolls. Meanwhile, if we are to

look for a laboratory that may have manufactured the novel coronavirus, we

should look to Wuhan, not Maryland. The Soviet Union, after all, produced

disinformation about American bioweapons when it was secretly conducting the

world’s largest illegal secret biological weapons programme,

Biopreparat.

At the same time, due

to the nature of the Chinese one-party regime, Xi’s foreign affairs may be

undermined by the same crippling sycophancy that beleaguered the Soviets. Xi’s

regime does not incentivise intelligence officers to

think independently and challenge political orthodoxy but instead places a

premium on filtering out anything the Chinese leader does not want to hear. If

history is any guide, when Chinese archives are one day hopefully opened, we

are likely to find a similar chasm between the Chinese government’s ability to

collect intelligence and its ability to accurately assess it – just as we saw

in the Kremlin. Former MI6 deputy chief Nigel Inkster, a China expert, put his

finger on the issue when he noted: ‘Rather as with the KGB, the difficulty has

been in telling truth to power.’ After the Twentieth Party Congress in 2022,

Xi’s politburo is stacked with loyalists. This raises the alarming prospect

that Xi is making consequential decisions, such as about Taiwan, based on

yes-men – his politburo is all male – and warped intelligence. Doing so

increases the chances of a Chinese miscalculation. Chinese industrial

espionage, stealing Western research and development, was the story before the

coronavirus pandemic. Since then, China’s Belt and Road projects have stalled.

Beijing has pivoted from traditional infrastructure investment abroad to new

health, digital, and green Silk Road

initiatives, which emphasise the benefits of trade

with China. But something else is now also underway. China has identified

thirty-five strategic technologies that it depends on from imports, so-called

chokepoint technologies, vulnerable to supply chain disruption.

China is innovating

those technologies for itself, insulating itself from Western disruptions. We

shall see whether Xi’s strategy is successful. The latest information available

as this book goes to print, from leading US cybersecurity companies like CrowdStrike,

is that Chinese hackers are moving from theft of Western R&D to insertion

of malware. This can be used to sabotage

infected systems.

Hong Kong, China’s

‘special Administrative Region, previously one of the most enterprising

societies in the world, Hong Kong now offers a chilling indication of what

Beijing has in store for territories it considers its own – like Taiwan, the democratic island off China’s coast.

Hong Kong’s latest new national security law rammed through its compliant,

handpicked parliament during the Covid pandemic in June 2020, effectively ended

political opposition here, allowing Chinese authorities sweeping jurisdiction

to surveil, detain, and arrest ‘subversives’ – invariably pro-democracy

activists. The British consider it a breach of the 1984 Sino-British Joint

Declaration, which provided for Hong Kong to remain autonomous – ‘one country,

two systems’ – for fifty years after the 1997 handover. A watershed moment

occurred in March 2022, when British judges withdrew from Hong Kong’s top

court, the Court of Final Appeal, where they had sat since the handover (as

they had under British rule). Hong Kong’s new national security law made their

presence ‘no longer tenable,’ because the administration had ‘departed from

values of political freedom, and freedom of expression,’ according to the head

of Britain’s Supreme Court in London. Meanwhile, Singapore, with its rule of

law, vibrant culture, and efficient government, seems set to take on Hong

Kong’s mantle as Asia’s most dynamic city-state.

In February 2022, on

the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Putin held a meeting with President Xi

in which they declared themselves to be in a partnership with ‘no limits.’

Russia and China’s partnership is an express effort to overturn the US-led liberal

democratic order. According to Xi and Putin, the US uses democracy and human

rights as a pretext to impose its will on other nations. The US ‘attempts at

hegemony,’ wrote Xi and Putin, ‘pose serious threats to global and regional

peace and stability and undermine the stability of the world order.’ The West

is decadent, and in decline. As Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov put it in a tweet: ‘We are at

the beginning of a new era, a movement towards real #multilateralism, not the

one which West tries to impose based on the “exceptional role” of the Western civilisation in the modern world. The world is much richer

than just Western civilisation.’ Putin has been

howling similar words since his 2007 Munich speech.

Putin and Xi mean

what they say: that liberal democracy is not up to the task of responding to a

world in crisis. Xi reportedly told Joe Biden that only autocracies can provide

the rapid responses needed to address the challenges of the modern world, from

pandemics to disinformation. The United States, with its pesky freedoms,

performed badly when it came to the Covid pandemic. (Earlier Chinese

propaganda, criticising America’s handling of the

pandemic, has since become a distant memory given the brave, open criticism in

autumn 2022 by Chinese citizens of their own government’s disastrous zero-Covid

policy.) The painfully apparent dysfunction of the United States political

system nevertheless offers endless, easy propaganda victories for the CCP,

whose membership is larger than Britain’s population: Donald Trump’s torrent of

lies and conspiracy theories, in and out of office, the polarisation

of US society, which culminated with a white

supremacist insurrection on the Capitol in January 2021.

The Cold War is not a

perfect analogy for the world’s contemporary superpower clash. Cold War 2.0 is

not simply a repeat of Cold War 1.0. China’s economic and technological

integration with the rest of the world, and other countries' dependence on

Chinese manufacturing, makes geopolitical relations with China significantly

more complex – and more dangerous. Unlike contemporary China, the Soviet Union

never made much that the rest of the world wanted. The country was a pariah.

The US economy was a goliath. That is not the same now. China is the top

trading partner for more than half of all countries and is Europe’s biggest

source of imports. At the end of 2021, China held roughly $1 trillion of US

debt. Little wonder that Secretary of State Antony Blinken performs linguistic

acrobatics to avoid calling US-China relations a ‘Cold War.’ (He knows how

trade can be used as weapons between East-West superpowers, having written a

book about the Soviet-Siberian natural gas pipeline in the 1980s.) The Biden

administration’s 2022 national security strategy likewise emphasises

that the US does not seek a new Cold War. That, of course, overlooks one of

this book’s central conclusions: Western powers can be in a Cold War

irrespective of whether they seek one and before they recognise

it.

There are other

differences too. The Cold War was characterised by

universalist, incompatible ideologies. Unlike the Soviet Union, the Chinese

politburo today does not espouse a universalist philosophy. Like Russia,

China’s bid for global power is based on ethnonationalism. Someone who looks

like me can never become Chinese, though I could have become a Soviet fellow traveller and even a citizen (Russian racism, however, was

never far from the surface in the Soviet days). China’s intelligence offensive

today is also more expansive than anything the Soviets could muster. The

latter’s intelligence offensive during the Cold War was traditionally focused

on specific targets. China’s strategy is much broader, a whole-of-state

approach, using a ‘human wave,’ or a ‘mosaic,’ or ‘a thousand grains of sand’

to vacuum up foreign intelligence and overwhelm American counterintelligence.

That said, the Cold

War is still a useful paradigm. It is the only precedent we have for a

sustained intelligence superpower clash. Both sides today, East and West, have

nuclear weapons. (China wishes to increase its warheads from about 350 to 1,000

in 2030, compared to America’s reported 5,500.) Unlike with the Soviets, there

are no effective nuclear arms limitation agreements between the US and China.

As in the Cold War, relations between both sides today rest on the principle of

mutually assured destruction. ‘A nuclear

war cannot be won and must never be fought,’ as Reagan liked to say. While

there is not a clash now between communism and capitalism, this century’s

struggle does have an ideological component to it: between authoritarianism and

liberal democracy. This is not just rhetoric, or talking points for pundits on

CNN. Both sides, East and West, espouse the benefits of their different,

divergent forms of government. They are each seeking to contain the other, in

yet another struggle for the future order of the

world.

The full scale of the

Chinese onslaught on the West is only now being appreciated. In 2020, the House

Intelligence Committee reported that, without a significant realignment of

resources, the US intelligence community would not be prepared to meet the challenge

posed by China this century. The US government has only recently awakened to

the nature of this onslaught, and the damage done, and is struggling to catch

up. If I were to situate where we in the West are today compared to the last

century’s Cold War, based on public information and trends, I would place us at

approximately the year 1947: Western intelligence services are alert to the

nature of the national security threat, are turning their sights to it, but

they are chasing a horse that has already bolted the stables.

Matters are

improving. In October 2021 the CIA, under the leadership of the veteran

diplomat William ‘Bill’ Burns, established a China Mission Centre. According to

Burns in 2022, the CIA plans to double the number of Mandarin speakers in the coming years, though

that does not tell us much, without knowing how many Mandarin speakers were in

the agency before. MI5 tells us that its Chinese investigations have grown

sevenfold since 2018 – but again, from what number is unclear. Intelligence

collection, especially espionage, alas cannot be turned around quickly.

What about the

future? How this century’s clash of superpowers turns out is, of course,

impossible to know. As Joseph Nye, former chairman of the National Intelligence

Council, has reminded us, there are only future scenarios, not certainties. But

I will leave you with observations about where we seem to be heading, based on

where we have been. History, as Churchill noted, is a guide for the present and

what may lie ahead. Applied history is most usefully understood as history that

informs the present – a phrase I have borrowed from Paul Kennedy.

As Mark Twain used to

say history does not repeat itself, but it does rhyme. In the geopolitical

standoff between the United States and China, we can already see what those

rhymes will be: emerging technologies that will define our lives in the

twenty-first century, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and

biological engineering. They are this century’s equivalent to atomic secrets in

the last. While last century’s superpower contest involved an arms race for

nuclear superiority and computing, this century’s contest will involve a race

for the control of data. The West does not appear to be winning the sprint for

AI.

According to the

Pentagon’s former software chief, who resigned in November 2021, the US

government has already effectively lost the battle to China over AI.

China’s massive data

collection strategy, across the globe, is ‘collect and store now, decrypt

later.’ This is where the East-West race for quantum computing poses such

dangers. By using subatomic particles, quantum computing will render obsolete

our existing public key encryption systems, which hitherto have been the

backbone of Internet cryptology. Whoever masters quantum will be able to

decrypt the data they have stolen and stored that uses public key encryption.

China is currently trailing Western companies like IBM in the race for quantum

computing – but it is catching up. The threat that quantum computing poses to

existing cryptology, however, is not as dire as even recently thought. As of

autumn 2022, private Western companies are offering open-market encryption

services invulnerable to quantum computing. The task for Western companies, and

governments alike, is to migrate existing and future data into such protected

systems starting now.

While there is thus a

‘fix’ to quantum, another looming threat, lies with the vulnerability of the

five or six big private companies that provide security certificates for the

internet. The internet relies on them. The companies are vulnerable to human penetration

or sophisticated cyberattacks. One company, RSA, already has been exploited.

Penetrating them would allow an actor to read encrypted communications, using

their certificates.

Another rhyme with

the Cold War is likely to be the influence of non-aligned countries, which will

again doubtless use the East-West clash for their ends. India has chosen to

align itself, yet again, with Moscow. Will Xi and Putin’s alignment with ‘no limits’

develop into a Bloc, a kind of Warsaw Pact 2.0, to rival NATO? Will there be a

split between China and Russia, like the Sino-Soviet rupture? Will Western

intelligence agencies be able to help policymakers exploit such a split?

Perhaps the war in Ukraine will become like the Korean War, a hot conflict in a

broader Cold War. And so on. It is unknown. Whatever the future has in store

for us, however, it is not difficult to see Hong Kong or Taiwan becoming last

century’s Berlin, contested cities, similarly buttressed by battalions of

spies. The application of history does have limits when it comes to informing

the present. Just as it is frequently a mistake to claim something is

‘unprecedented,’ it is equally mistaken to think there is nothing new under this

century’s rising red sun. We do live in a brave new world. We are on the brink

of the fourth industrial revolution, witnessing blurring boundaries between

physical, digital, and biological realms. This will fundamentally change how we

live, work, and interact with each other, in a way that will be as disruptive

to our societies as the first industrial revolution previously was.

Today’s

interconnected digital world is changing not only how we live, but also the

nature of intelligence and national security. All intelligence agencies are

having to rethink tradecraft. Maintaining espionage cover in an age of global

digital information is more difficult than it was even in the recent past. The

time of an analogue intelligence operation is over. Social media, and the

digital dust we emit as we use our phones – and are caught on CCTV, door or

dashcams – offer ubiquitous technical surveillance, forcing agencies to rethink

how they conduct traditional business.

In the past, Soviet

intelligence planned sabotage operations for the outbreak of hostilities

between East and West, during World War Three, by conducting physical

reconnaissance of critical infrastructure in Western countries and secretly

planting arms caches there for use during war. Today, there is no need for such

physical operations (though they do continue). Chinese hackers in the PLA’s

cyber unit, known as 61398 – as well as corresponding Russian, Iranian, and

North Korean units – can vault into the heart of Western governments and

critical infrastructure, planting malware on computer operating systems for

activation like delayed-action booby traps. Today approximately 85 per cent of

US critical infrastructure lies in the private sector, which dramatically

increases the attack surface for a hostile state like China.

Our new globalised information environment has inverted the nature

of intelligence. During the Cold War, it is estimated that US intelligence

derived 80 per cent of all its collection on the Soviet Union from secret

sources, namely technical collection and espionage, and 20 per cent from open

sources. Now those proportions are believed to be reversed. Governments no

longer hold a monopoly on intelligence. The future of intelligence lies with

the private sector, not with governments. Open-source (or commercially

available) data is already transforming the landscape of intelligence, leading

to an existential crisis among Western agencies. Outfits like Bellingcat and

C4ADS are revealing secrets about Russia and China, respectively, that

traditionally would have taken an intelligence service huge resources and time.

(Even then, success would not have been guaranteed.) Another open-source

intelligence start-up, Strider Technologies, has shown that the Chinese

government is exploiting scientific research collaborations at Los Alamos to

advance its defence industries in dual-use

technologies like hypersonics. The echoes of the

first Cold War – Los Alamos, home of the

Soviet atom spies – are blindingly obvious. As in the last Cold War, the US

government is effectively funding an adversary’s defence

industry. US government research grants for Chinese scientists at Los Alamos

have advanced Chinese S&T and decreased American competitive advantage.

Again, this information was derived from open, not secret, sources. Public

information about parking tickets, and patents, shines a light on what is going

on behind the digital and bamboo Iron Curtains. To stay relevant and continue

to provide a margin for decision-makers, traditional secret services like MI6

have to come out of the shadows, embrace, and integrate with new technologies

that can turn complex data into insights. This reiterates that this century’s

East-West intelligence war will be about data and who can best exploit it,

through machine learning and AI.

The history of the

last century’s epic intelligence war offers seven lessons for the superpower

struggle now unfolding between the United States and China.

First, the best defence is good intelligence. Given the unprecedented

Chinese assault on US secrets, good intelligence – timely, accurate, and

relevant information – will be key for Western policymakers to act decisively

about Chinese intentions and capabilities.

Second, intelligence

in this century will increasingly be dominated by open-source information.

There will continue to be a niche for traditional espionage. A well-placed spy

like Oleg Gordievsky can give insights into a

foreign leader’s mindset, and thinking, that would remain mysterious with even

the best open-source intelligence. The West must seek such sources. An ironclad

rule from the last century is that spies catch other spies; the same will be

true this century, requiring Western intelligence services to penetrate China’s

intelligence agencies to protect our secrets. But outside this niche area for

traditional espionage, this century’s intelligence war will be about

open-source data and the scientists who can exploit it. The age of a Secret

Service is over.

Third, Western

strategy regarding China must be based on strategic empathy. It would be a

mistake to put forth a grand strategic doctrine like NSC 68, which set out the

US government’s strategy to contain the Soviet Union but failed to address how

that doctrine would appear to those in Moscow. NATO made a similar strategic

miscalculation after the Soviet Union’s collapse when it failed to understand

Russia’s deep sense of humiliation and its intense desire to protect its

‘national interests.’

Fourth, Western

policymakers must use covert actions cautiously: they have limited practical

effect, can result in unforeseen consequences (‘blowback’), and tend to

embitter relations between superpowers. Whether it is regime change, degrading

alliances, or discrediting targets, covert actions are only effective when they

supplement diplomacy and statecraft. Seductive as they are as a quick fix for

failed diplomacy, covert actions cannot replace overt foreign policy. Outside

of the Soviet-Afghan war, and perhaps US support for the anti-Soviet Solidarity

movement in Poland (QRHELPFUL), it is difficult to think of a single US covert

action that provided a long-term strategic success.

Fifth, information

warfare in this century’s cyber age will continue to involve the insidious

spread of disinformation, which can cause us to question the existence even of

facts and truth. ‘Truth decay’ cannot be solved by Western clandestine services

alone – that is the true lesson of US efforts to counter Soviet disinformation.

Intelligence agencies of democracies can do their best to counter online

disinformation. But their efforts will never be sufficient; like chopping off a

hydra’s head, more spring up on social media. The answer to the challenge of

algorithmically driven disinformation lies with the patient, long-term

education about online information – digital literacy. What is required is a

broad-based public-private effort, a new Marshall Plan of the Mind.

Sixth, the

intelligence war between East and West will persist whatever happens overtly

with relations between China and the US, whether they improve or deteriorate.

Russia, past and present, has used its intelligence services offensively

against Western countries when their defences were

down, as a result of improved relations, or when they were distracted

elsewhere. There is no reason to believe that China would not do the same.

Western governments must be alert to this and expect it. Seventh, and finally,

the US government must be as transparent as possible about the known nature and

scope of Chinese espionage and other illicit activities. Chinese clandestine

efforts must be disclosed, challenged, and debated.

One of the major

conclusions from last century’s intelligence war between East and West is that

two incompatible things can be true at the same time. Just as with Soviet

espionage, Chinese espionage can be real – and Western democracies can create

McCarthyite witch scares. Chinese intelligence actively recruits from Chinese

diaspora populations, but few Chinese Americans become spies. They are

frequently victims of Xi’s regime. Operation FOXHUNT involves Chinese

intelligence officers targeting, capturing, and repatriating Chinese citizens

overseas who are considered to be political threats, often by using threats to

family still residing on the mainland. Over eight years, about nine thousand

people worldwide were hauled to China as part of FOXHUNT, some of them US

nationals. While the Chinese government undertakes every kind of covert

activity, the FBI also makes mistakes. The FBI wrongly accused a professor at

Temple University, Xiaoxing Xi, a naturalised

American citizen and world-renowned expert on superconductor technologies, of

being a Chinese agent. The same happened to Gang Chen, an MIT professor. He was

cleared in January 2022 after a lengthy DoJ

investigation but is stepping away from federally funded research because of

anxiety about being racially profiled.

There is a real

prospect of a new Red Scare, targeting US citizens who happen to be of Asian

descent, chilling free speech and academic freedom, with innocent citizens of

Western countries wrongly accused of being Chinese spies. We do not know

whether Charles Lieber, former chair of Harvard’s Department of Chemistry and

Chemical Biology, was a Chinese agent. He has been convicted of taking Chinese

money, which he hid from Harvard and the National Institutes of Health. That

does not necessarily make him a spy – he may simply have made bad decisions. It

is time for an urgent public policy conversation about the nature of Chinese

illicit activities in the West, and the balance that Western democracies are

prepared to strike between national security and civil liberties. Sunlight

remains the best disinfectant.

The American Century,

if we understand that to mean the age of America’s global leadership, so termed

by the American media magnate Henry Luce, is now

over. When the history of this period comes to be written, we may well conclude

it came to an end in 2016. Under a president willing to ride roughshod over

norms and laws, the United States experienced the seductive pull of

authoritarianism. Strong leaders, the cliché says, can ‘get things done.’ One

of America’s foremost experts on Russia, Fiona

Hill, has concluded that the United States risks becoming like Russia.

Given the levels of nativist populism, violence, partisan divide, political

corruption, and a recent coup attempt in the US, it is hard to disagree with

her. (Trump, inevitably, dismissed Hill, who is English-born, as a ‘deep state

stiff with a nice accent.’) In 2017, the Economist Intelligence Unit downgraded

the United States to be a flawed democracy. It has remained such in reports

since. American democracy has arguably gotten worse, rather than better, in the

years since. America has many similarities to the corruption and mob rule that

the ancient historian Polybius wrote about, in the quote at the beginning of

the chapter, when explaining the rise of the Roman republic (read: China) to

replace the Greek city-states (America) as the dominant Mediterranean power.

The ultimate damage

that Trump inflicted on American democracy lies with the Big Lie: his claim,

without evidence, that he did not lose the 2020 election – that it was ‘stolen’

from him. The refusal of Trump to concede that he lost, fearing he would be branded

a loser, was insidious enough. But then, on 6 January 2021, he helped to

instigate a coup attempt at the Capitol to

overturn the election result. He was indifferent about his vice president being

killed for his ‘betrayal’ – for not being loyal enough to the president to

ignore US law and join in Trump’s plan.

This is the stuff of

tin-pot dictatorships. It has a direct precedent, as we saw earlier in Chile

when the US government tried to rig the election of Allende. Swap the name

Biden for Allende, and the parallels with Trump’s effort to suborn electors to

overturn the 2020 election hit you in the face. Both tried to pressure electors

not to ratify a democratic election. What the US government did overseas in the

past is now being done at home. Speaking in October 2022, former CIA director

Michael Hayden, who spent a career analysing

dangerous foreign regimes, said that he believes the US has a fifty-fifty

chance of surviving.

If you travelled

overseas as an American during Trump’s presidency, it became quickly apparent

that his administration made our country into a laughingstock on the world

stage. Trump’s America appeared like a crumbling edifice, like his former Taj

Mahal in Atlantic City. Since Putin’s war in

Ukraine, the Republican Party has tried to rewrite its recent past, but we

should not forget that in the 2020 US election, Trump used Russian

disinformation, claiming that Ukraine, not Russia, was responsible for meddling

in the 2016 election. He then tried to withhold crucial weapons for Ukraine and

attempted to blackmail the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, earning

Trump the first of his two unprecedented impeachments by the House of

Representatives.

When Barack Obama was

elected president in 2008, I thought – naively – as an American who has lived

overseas most of my life, that the issue of racism in the United States had

finally been consigned to history. Instead, Obama’s presidency threw fuel on a

simmering fire of racism in US society. Trump’s presidency appealed openly to

the country’s nativist fears, and to white nationalists, who were eager for a

champion. He encouraged fringe ideas and conspiracy theories, like QAnon, which holds that Democrats are a cabal of satanic paedophiles and cannibals out to sabotage Trump, to become

respectable and mainstream. (Its leader, Q, holds a Q-level security clearance,

used for nuclear secrets, and therefore knows what is ‘really’ going on, you

see.) Hostile foreign governments like Russia saw the paranoid strain in US

politics and exploited it.

The US domestic

situation is dire. That said, China’s continued economic rise is not

guaranteed. President Xi may be physically

imposing, at nearly six feet, but China is not ten feet tall. Beijing has had

to impose emigration restrictions to stop a brain drain from China. Xi’s ‘China

Dream’ may already be over, and could become a nightmare through a war with Taiwan,

for example. Worryingly for the rest of the world, a China in decline may

become an even more dangerous player. As Russia shows, a superpower that never

achieves the global dominance it believes it deserves is a dangerous one,

capable of unleashing an aggressive clandestine foreign policy. Decline

increases risk-taking.

For all the West’s

problems, most people, I believe, would still rather live in the United States,

Britain, or, if you are lucky enough, Europe, with their democratic freedoms,

than under China’s digital authoritarianism. I am free to criticise

the US government in ways that would land me in jail in China or Russia. As

Winston Churchill said, democracy remains ‘the worst form of government –

except for all the others that have been tried.’ Democracy and freedom are also

worth fighting for, as Ukrainians are bravely showing. Russia’s war in Ukraine

will hopefully lead to a renaissance of democracy over authoritarianism. With

luck, that will be the history of our future, the next chapter of the epic

intelligence war between East and West.

For updates click hompage here